Creative: Food Tarot Toolkit

Markéta Dolejšová

Markéta Dolejšová is a design researcher working across the interrelated domains of eco-social sustainability and food systems transitions. Her practice-based research seeks to connect stakeholders across food-oriented design, research, and practice who are interested in experimenting with diverse co-creative methods to foster regenerative, more-than-human food futures. She is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Aalto University in the School of Arts, Design and Architecture (FI), researching creative practices for transformational futures (CreaTures project).

Introduction

Food and food practices are essential elements of everyday life. The global more-than-human food web is a complex composite of substances, processes, and meanings that are woven together by diverse eaters following distinct personal, biological, cultural, and economic values and motives. The ways that nutrients and relations flow through food systems are problematic. Far from being nourishing and regenerative, current modes of food production, distribution, consumption, and disposal are causing ill health and amplifying climate change.[1] Identifying and maintaining more sustainable and just foodways is essential for life on the planet to thrive.

Food system transformation has been of a central interest of many food practitioners. To address food system issues, various methods and tools have been experimented with, frequently using technological innovation.

Food-Tech Innovation

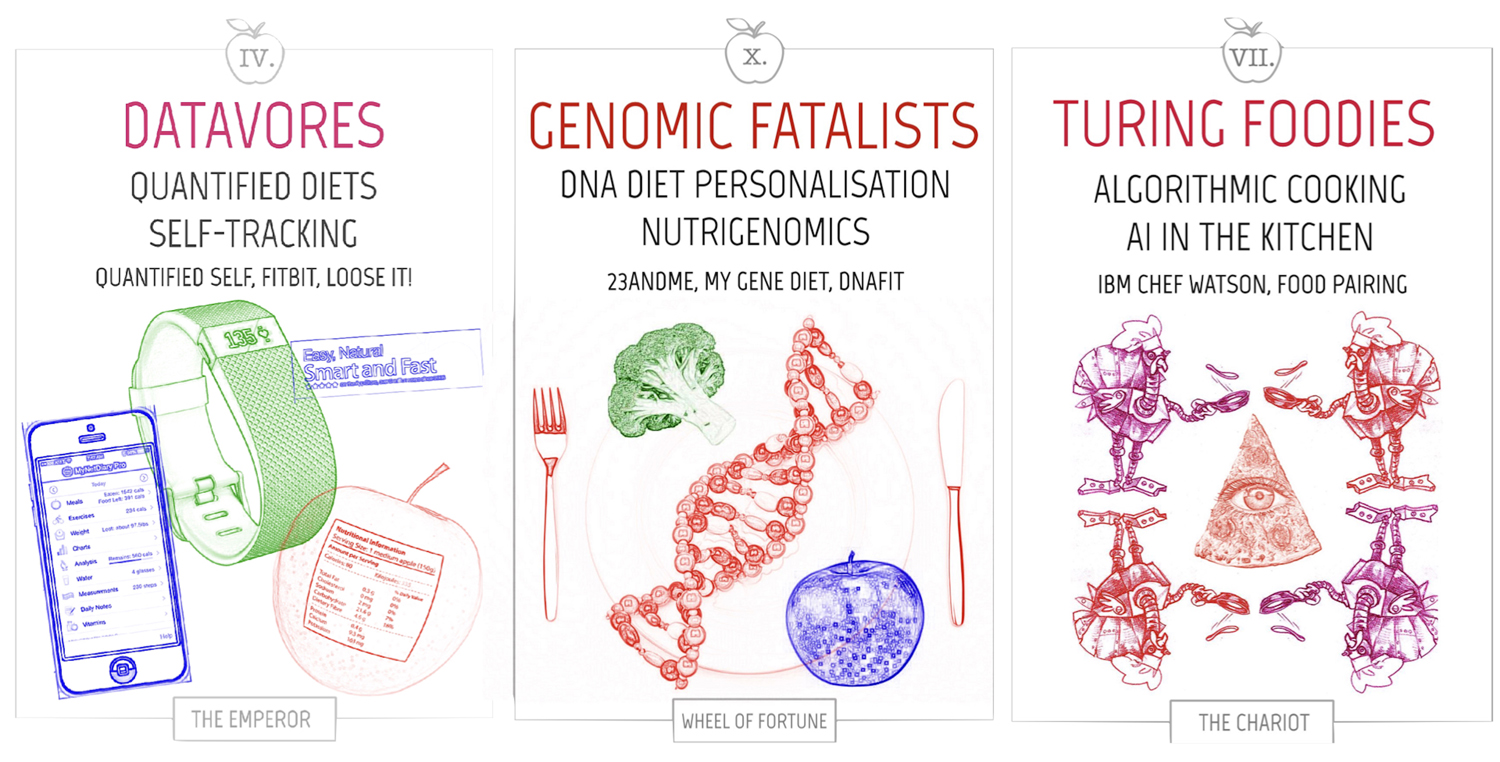

While the use of technology in food processes is not new (think of spears, plows, butter churns), recent years have seen a rapid growth of the digital food-tech sector.[2] From AI-based kitchenware and online diet personalization services to food sharing apps and digital farming platforms, food-tech designers, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists began proposing solutions for better food practices.[3] (See Figure 1.)

These food-tech services and gadgets carry a promise of more efficient food futures, but they also raise concerns. How are food-tech solutions having an impact on social and cultural food traditions? How are they changing eaters’ creative involvements with food? Is it safe to rely on recipes and diets designed by algorithms? How is the growing food-tech innovation affecting the food job market? How could generic, universalising techno-solutions cause long-term, sustainable behavioral changes across diverse food cultures and systems?

The Parlour of Food Futures

Concerns about human-food-technology entanglements are at the center of the Parlour of Food Futures project, which aims to provoke future food imaginaries and gather reflections from diverse eaters. Initiated in 2017 as a series of experimental food design research events[4] situated in various co-creative settings, the Parlour functions as a speculative oracle that explores possible food-tech futures through the 15th century game of Tarot.

The future food explorations are performed over a bespoke deck of Food Tarot cards that present 22 food-tech ‘tribes’, imagining how food and eating practices might look in the near future (Figure 2). Although primarily future-oriented, each tribe refers to an existing or emerging food-tech trend. For instance, Datavores refer to people who follow quantified diets and do health self-tracking. Turing Foodies is about the use of AI in the kitchen, and Genomic Fatalists refers to DNA-based diet personalisation (Figure 3).

During one-on-one Tarot readings, Parlour participants are prompted to discuss food-tech issues shown on their selected cards, share their experiences and reflections, and craft future food scenarios.

Food Tarot

The Parlour project is inspired by the Tarot technique, which has been traditionally used in card games, as well as for divinatory purposes and future speculations. Drawing on the Tarot inspiration, the project aims to provoke playful yet critical food engagements and support the notion of food futures as uncertain but always connected to the past and the present.

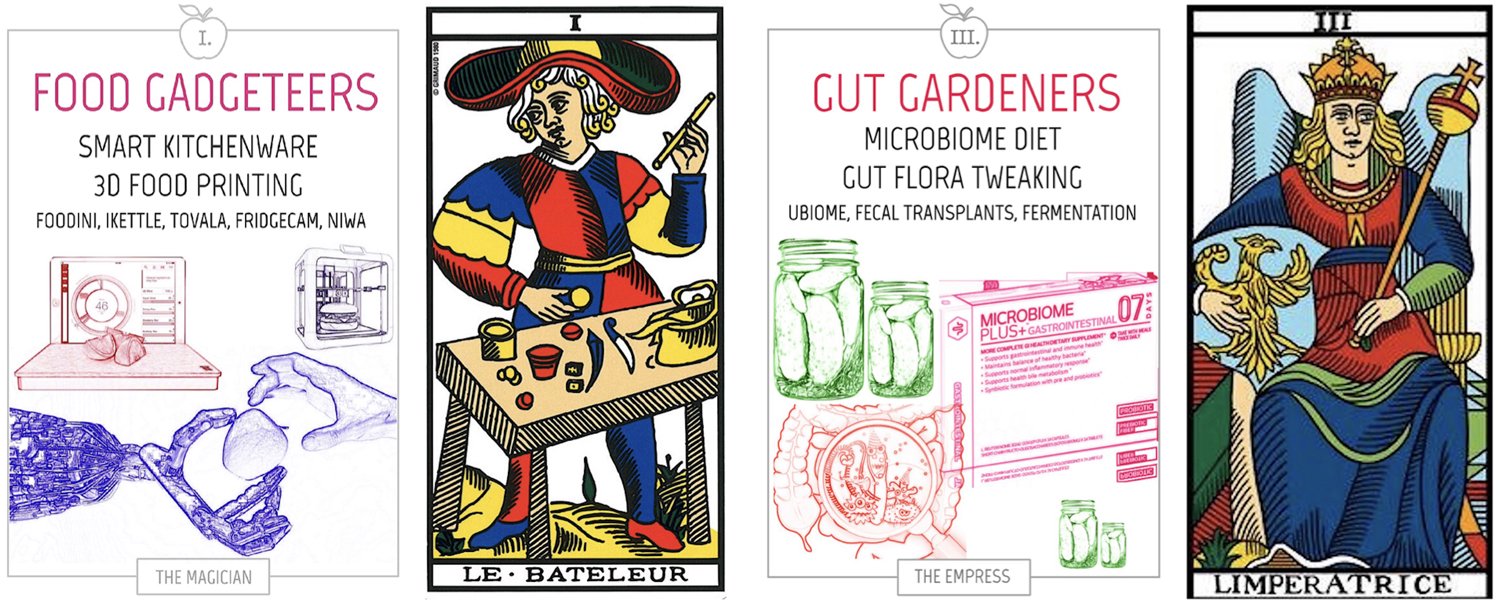

The Food Tarot cards are designed according to the Tarot de Marseille deck (focusing on the Major Arcana of Tarot). The Marseille deck includes 22 cards with various philosophical and astronomical motives, embodied by elements such as The Empress or The Magician. Each of these elements has a specific symbolic meaning, which we translated into the Food Tarot version.

For instance, the Tarot card of The Magician—signifying the potential for transformation—is matched with the diet tribe of Food Gadgeteers, who experiment with 3D food printing to transform ordinary food items into more spectacular forms. The Empress card—representing the dominion over growing things—inspired the food-tech tribe of Gut Gardeners, who experiment with DIY biohacking to grow their own food (Figure 4).

To arrive at the 22 imagined food tribes, we conducted a literature review of existing and emerging food-tech trends.[5] We then selected 22 trends that were most interesting to us and matched those with the original Marseille symbols, thereby creating the Food Tarot deck as an experimental design toolkit to help guide critical future food imaginaries.

Future Food Readings and Imaginaries

Between 2017 and 2021, we have performed the Parlour at more than 30 occasions, in venues accessible to diverse publics including festivals, exhibitions, workshops, classrooms, hackerspaces, and community gardens, as well as random street corners. Following our aim to engage diverse food practitioners, we have not set any specific requirements on participants’ skills and expertise: anyone can sit down for a reading and share what they know about food.

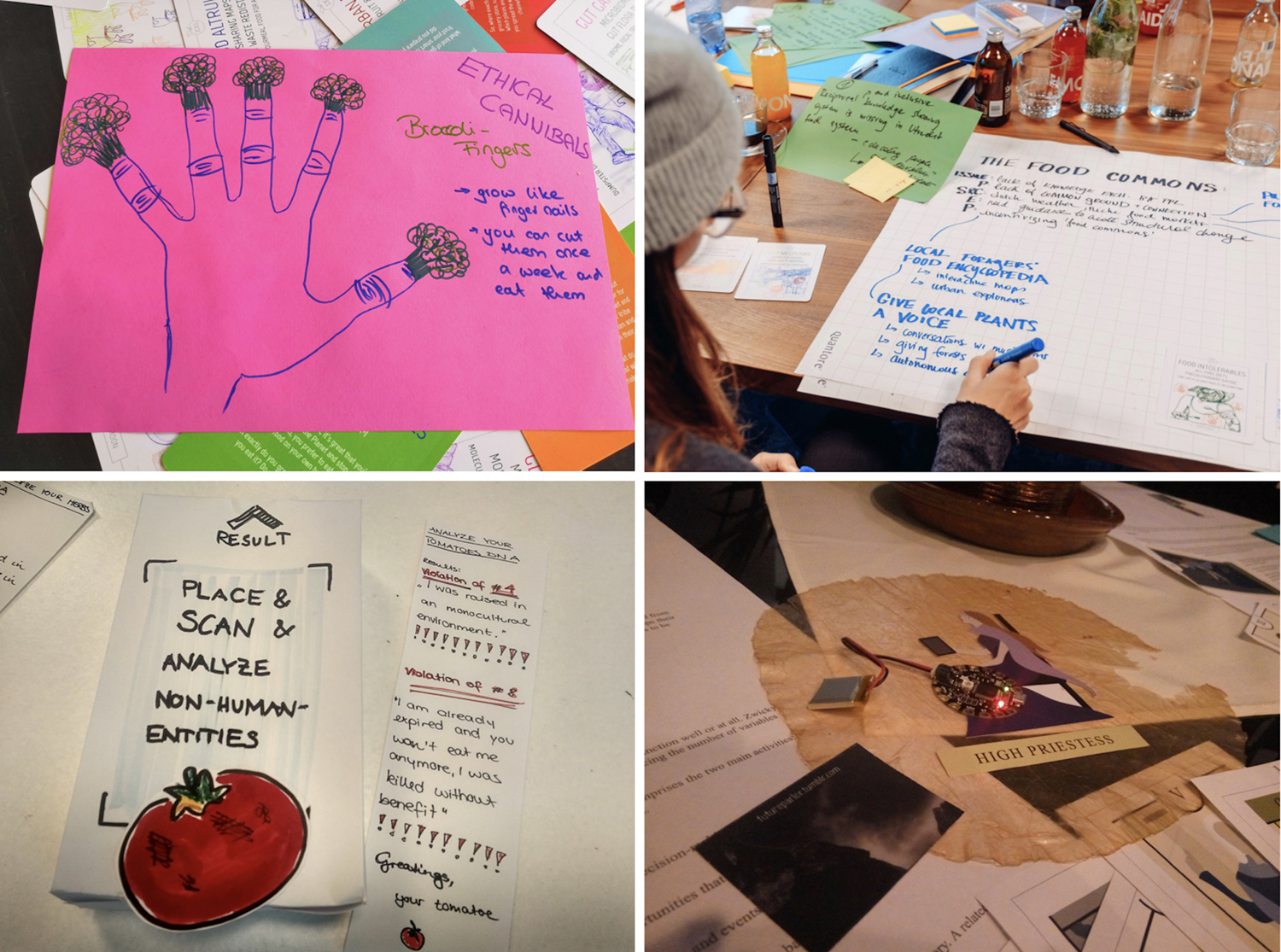

The Food Tarot readings are similar to readings performed in traditional Tarot parlours: a participant sits down, shuffles the deck, and picks a card. The reader initiates a conversation about the selected card and the food futures it represents, asking prompting questions about participant’s experiences and ideas.

Based on how the responses unfold, the reader keeps selecting a few additional cards from the deck that are either resonant or contrasting to participant’s responses. Eventually, the table ends up filled with a card collage—or a prophecy—representing a possible food future that reflects the reading conversation (Figure 5).

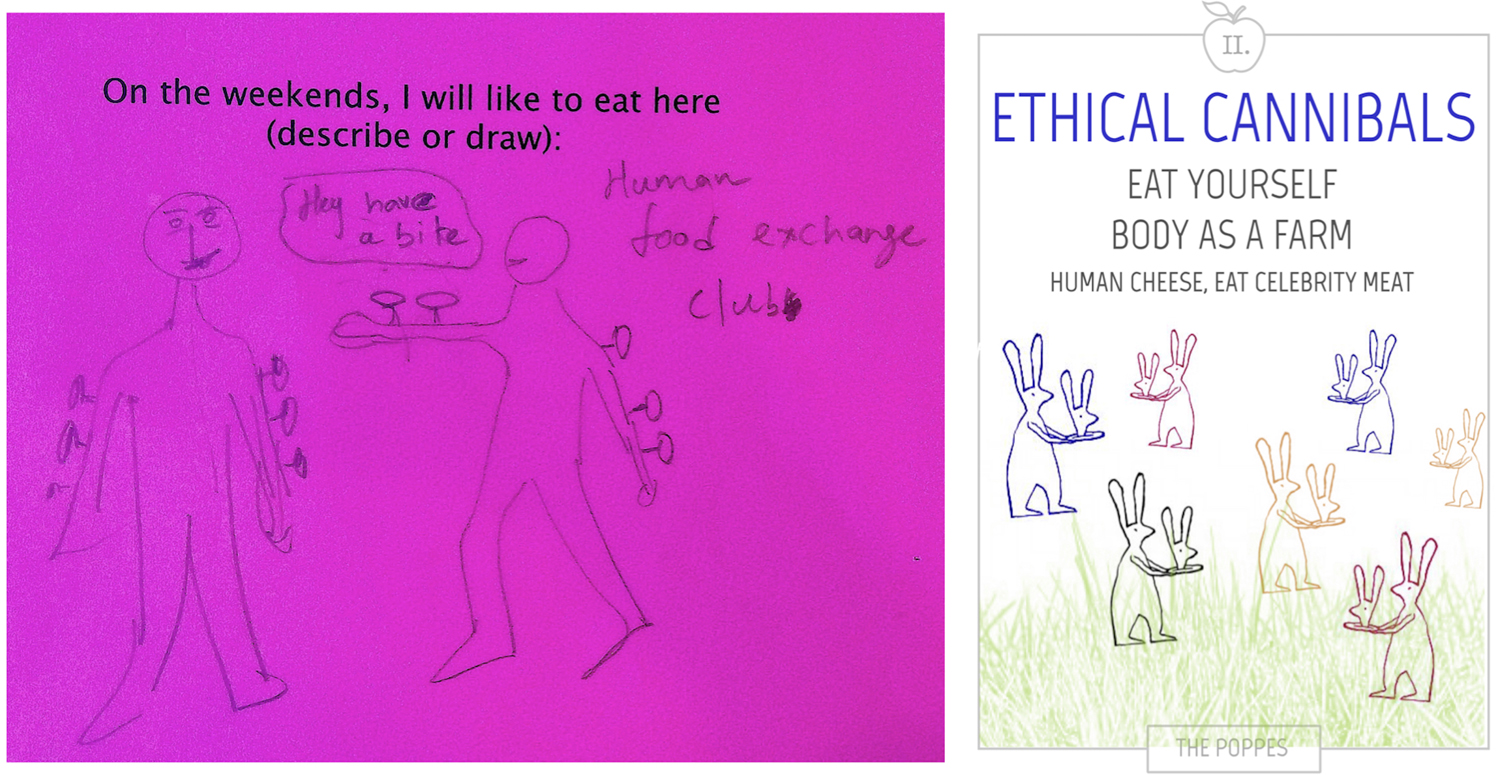

When a reading is finished, a participant is asked to select one card from the final collage that they feel is the most important. They then craft a short ‘what-if’ scenario imagining that they are a member of the selected food-tech tribe (Figure 6). A few scenario examples follow.

Human-food exchange club and social breastfeeding

Inspired by the card of Ethical Cannibals—dieters preferring to ‘eat themselves’ as an ethical alternative to consuming animal protein—a Parlour participant at the Emerge exhibition in Arizona (USA) proposed a scenario for convivial more-than-human food futures. In his imagined future as an Ethical Cannibal, he would consume special probiotics to tweak his gut flora and grow edible mushrooms on his skin. Instead of feeding just himself, he would share his harvest with others in the Human-Food Exchange Club—a community space for peer exchange of edible proteins cultivated in and on human bodies (Figure 7).

A similarly focused response to the Ethical Cannibals card was presented by a participant at the VVitchVVavve festival in Melbourne, Australia, who suggested the idea of social breastfeeding. Instead of breastfeeding only her baby, she imagined sharing the nourishing protein in her milk with a broader circle of friends and family, as well as with any other non-human animals in need of good nutrition.

Both scenarios reflect on broken global food supply chains and unevenly distributed food resources, proposing self-replenishing human bio-materials as a nutritious resource for human and non-human eaters. The implementation of the proposed ideas would require a radical shift in values, and the scenarios thus serve as a provocation, raising for debate the role of human bodies in supporting regenerative food futures.

Genomic surveillance & algorithmic chefs

During our reading of the Genomic Fatalists card, a participant at the Cross festival in Prague pointed out the growing volume of sensitive personal data that people share over online diet personalisation services (e.g., demographic and metabolic details, genetic information). Her scenario includes a drawing of herself walking in a street full of food shops—bakeries, ice cream parlours, cheese and wine boutiques—staring sadly into the shopping windows, unable to buy anything. (Figure 8)

As the participant explained, her bank card (in the scenario world) is connected to her personal genetic data profile, which is managed by her health insurer. Aiming to keep their clients fit and profitable assets, the insurance company does not allow her to purchase foods that are considered unhealthy.

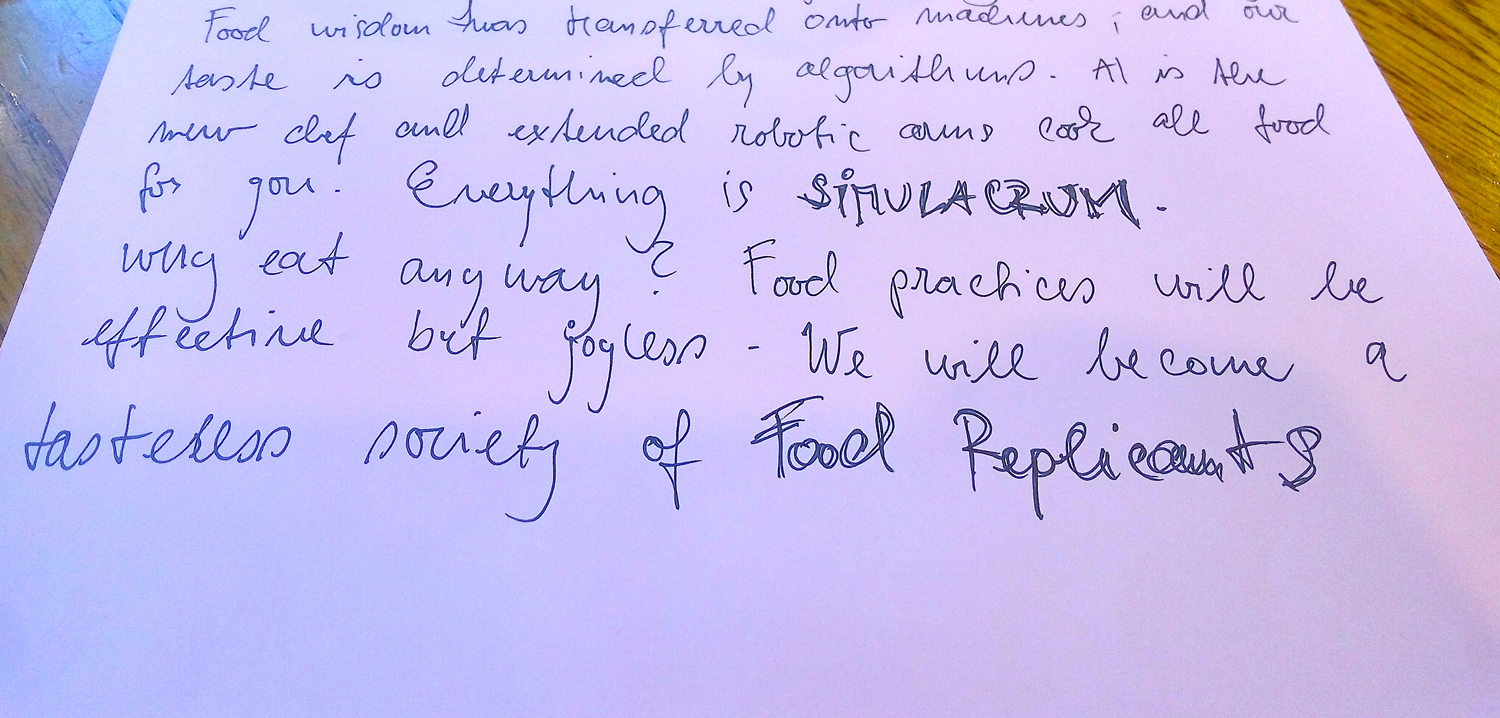

Reflecting on the Food Gadgeteers card, a young mother attending the Emerge Parlour highlighted the simulacral character of cooking with smart ‘AI-based’ food technologies: While having the illusion of preparing their food by themselves, users rely on algorithmic commands prescribed by smart machines, such as automated, remote-controlled ovens and ‘intelligent’ cookbooks.[6] In her scenario, she envisioned a Food Gadgeteers future in which people stop eating food altogether and become Food Replicants. (Figure 9)

These dystopian scenarios illustrate concerns with the potentially nefarious role of novel food technologies, as surveillance tools restrict people’s personal choices and agency. Their creativity as cooks as well as their gustatory joys are inhibited by the cold efficiency of vigilant algorithmic chefs.

Towards Transformative Food Futures

Since the start of the Parlour project, we have collected hand-written notes from over 160 Food Tarot readings and the same number of participant-made scenarios. The scenario examples described above illustrate the kind of critical, imaginative reflections that the experimental Food Tarot toolkit can provoke. The personal food-tech reflections shared by Parlour participants are both optimistic and sceptical, provocative and practical, whimsical and serious. They touch upon broader social circumstances of food-tech innovation as well as personal food-tech contexts. The breadth of these ideas illustrates a variety of perspectives on how to approach contemporary food-tech issues.

The cards do not provide instructive recipes for better food practices. Instead of being didactic, they provoke critical thinking, enable a space for playful learning and nurture imagination. They do not support transformative food action on a systemic level but they can help people reflect, and imagine how food futures might look—an essential, although only partial, step in any sustainable food transition.[7] It is vital to note that the experimental Food Tarot encounters in the Parlour have not been always reflective and inspiring. Sometimes, participants engaged on a rather superficial level, focusing on the aesthetic—and decidedly whimsical—aspects of the imagined diet tribes, rather than on the food-tech provocations that they carry. This is a limitation of the card deck as a critical design artifact.[8]

Besides performative readings in the Parlour, we have used the Food Tarot toolkit as a pedagogical prop in various food and design research courses and workshops. The data collected from readings and course observations helped us to make better sense of food-tech innovation and gain a deeper understanding of what technology can do in various social and cultural food contexts.[9] As a toolkit for experimental food practitioners, the Food Tarot deck is available for free, under a Creative Commons license.

References

Dolejšová, M. (2016). A Taste of Big Data on the Global Dinner Table. Journal for Artistic Research, issue 9, 2016. https://doi.org/10.22501/jar.57801

Dolejšová, M. (2018). Edible Speculations: Designing for Human-Food Interaction. Doctoral dissertation, National University of Singapore.

Dolejšová, M. (2021). Edible Speculations: Designing Everyday Oracles for Food Futures. Global Discourse, 11:1-2. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/204378920X16069559218265

Dolejšová, M., Khot, R.A., Davis, H., Ferdous, H.S., Quitmeyer, A. (2018). Designing Recipes for Digital Food Futures. In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ‘18). ACM, New York, NY, USA, Paper W10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170427.3170622

Dolejšová, M., Wilde, D., Altarriba Bertran, F., and Davis, H. (2020). Disrupting (More-than-) Human-Food Interaction: Experimental Design, Tangibles and Food-Tech Futures. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/3357236.3395437

Emergen Research (2021). Food Tech Market By Technology Type (Mobile App, Websites), By Service Type (Online Food Delivery, Online Grocery Delivery, OTT & Convenience Services), By Product Type (Meat, Fruits and Vegetables, Dairy), and By Region, Forecasts to 2027. Report ID: ER_00464.

Lupton, D. (2017). Cooking, eating, uploading: digital food cultures. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Food and Popular Culture, pp. 66-79.

Norton, J., Raturi, A., Nardi, B., Prost, S., McDonald, S., Pargman, D., Bates, O., Normark, M., Tomlinson, B., Herbig, N. and Dombrowski, L. (2017). A grand challenge for HCI: food + sustainability, interactions, 24(6): 50-55.

Wilde, D., Dolejšová, M., van Gaalen, S., Altarriba Bertran, F., Davis, H. & Raven, P.G. (2021 – upcoming). Troubling the Impact of Food Future Imaginaries. Proceedings of the 2021 Nordic Design Research Conference (NORDES).

Willett, W. et al. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet 393, 10170, 447-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

- Willet et al., 2019. ↵

- Emergen Research, 2021. ↵

- Dolejšová 2016; Lupton, 2017; Norton et al., 2017. ↵

- Dolejšová et al. 2020. ↵

- See details in Dolejšová, 2018. ↵

- See details in Dolejšová 2018. ↵

- Wilde, Dolejšová, et al. 2021. ↵

- See Dolejšová, 2021 for details. ↵

- For details of Parlour research, see Dolejšová, 2018; 2021. ↵