Case: Food Traceability

Blue Miaoran Dong

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Identify food traceability technologies, infrastructures, and corporate capitals that compose the Chinese food traceability system.

- Describe the limitations of the food traceability system relative to its public claims (like perfect transparency).

- Explain the potential harm and environmental impacts stemming from the food traceability system.

Introduction

Chinese Citizens are increasingly interested in knowing where their food comes from and seeking information about the conditions in which their food is produced. But how much detail is necessary? Do you need to know who is growing your crops, or how farmers feed the animals they raise? Would you be willing to pay a premium price for that information? Both the Chinese government and Chinese corporations are convinced that the answer to all of these questions is a resounding yes.

Context

Mounting food safety incidents and food fraud can endanger citizens and cost the global food industry billions of dollars every year. Traceability apps claim to give you the entire life story of your food by simply scanning a unique identification code attached to the food package. For instance, the identification code on an egg would allow you to know whether that egg was laid by the fittest hen. The hen would wear a device like a Fitbit on her ankle, which transmits live footstep numbers and other biometric data. Some premium egg farmers even have 360-degree surveillance cameras and face-recognition technology, to help you identify the hens in their farming environment. As the consumer, you can even choose a customized feeding plan for the hen, to ensure it lays eggs with a specific taste profile. On the one hand, this technology helps ensure animal welfare—i.e., that the hen has a nice environment for exercise and high-quality food to eat. On the other hand, this comes at a hefty price of privacy for consumers and augments social inequalities.

The Chinese government is enthusiastic about its food traceability system, which allows the government to pinpoint the source of food contamination more accurately, thus mitigating the risks of wide-scale, food-related disease outbreaks. But traceability also works as a goldmine for corporations to learn about their customers, to extract their personal information and expand the reach of their own business. There is a distinct difference between the Chinese and Canadian food traceability systems, in that the Canadian system does not trace forward to the customer. In other words, the Canadian system does not keep detailed consumer food preferences and purchasing habits; it only traces the food from origin to sales point. The Chinese food traceability system enables food corporations, food traceability technology providers, and the government to trace and track all kinds of consumer food preferences and eating habits. This information allows food corporations to create new hit products, or only produce those food items that sell in the greatest quantities, which in turn can decrease food diversity in the long run.

Tracing the Tracers

My interest in this rapidly developing technology sector led me to examine the financial reports of the big three Chinese technology corporations: Alibaba, Tencent, and JD,[1] which are playing essential roles in developing, distributing, operating, and transforming the Chinese food traceability system. This transformation accumulates substantial revenue in the hands of corporate actors. In the last ten years, food traceability apps available in China through Apple’s App Store have grown from 8 to 112, and from being available in 2 cities to 21. While this development trajectory prioritized coastal, eastern, and urban regions, it neglected rural and western regions, where citizens are still struggling to have an adequate internet connection and delivery service on which digital economies heavily depend. Amazingly, eggs with food traceability technology are 4 to 8 times more expensive than regular eggs. Evidently, not everyone can afford the well-traced food, and this is especially the case for people who live in rural regions.

Analysis

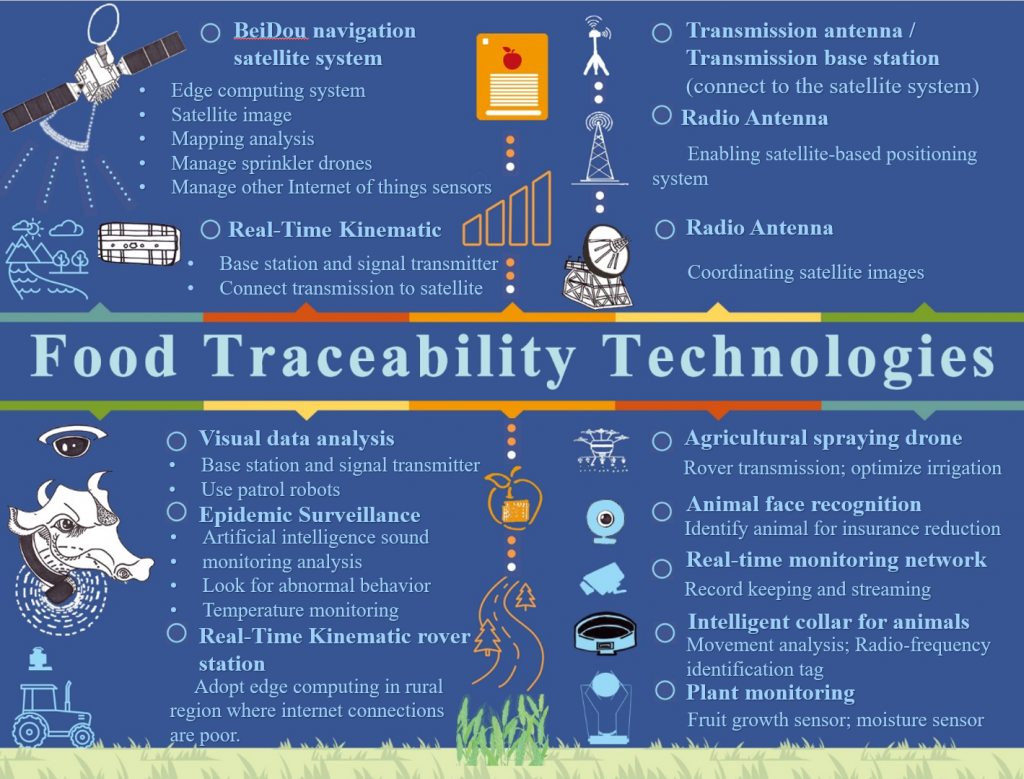

Figure 1 provides an overview of the food traceability technologies available as of 2021. The technologies include infrastructure hardware, the Internet of things (IoT), and computing capabilities. For instance, the Beidou navigation system enables the edge computing system to coordinate with Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) signal transmitter, RTK rover station, and radio antennas, which connect the transmission to the satellite. It also coordinates water sprinkler drones, IoT sensors, animal tracking collars, and plant monitoring devices to transmission base stations that coordinate orders for IoT sensors in the rural regions where internet connections are poor. Last, satellite systems combine satellite image, sensor data, and artificial intelligence analysis to generate an optimized irrigation action plan, provide animal early sickness alerts, and reduce insurance premiums with this heavily monitored and automated technology system.

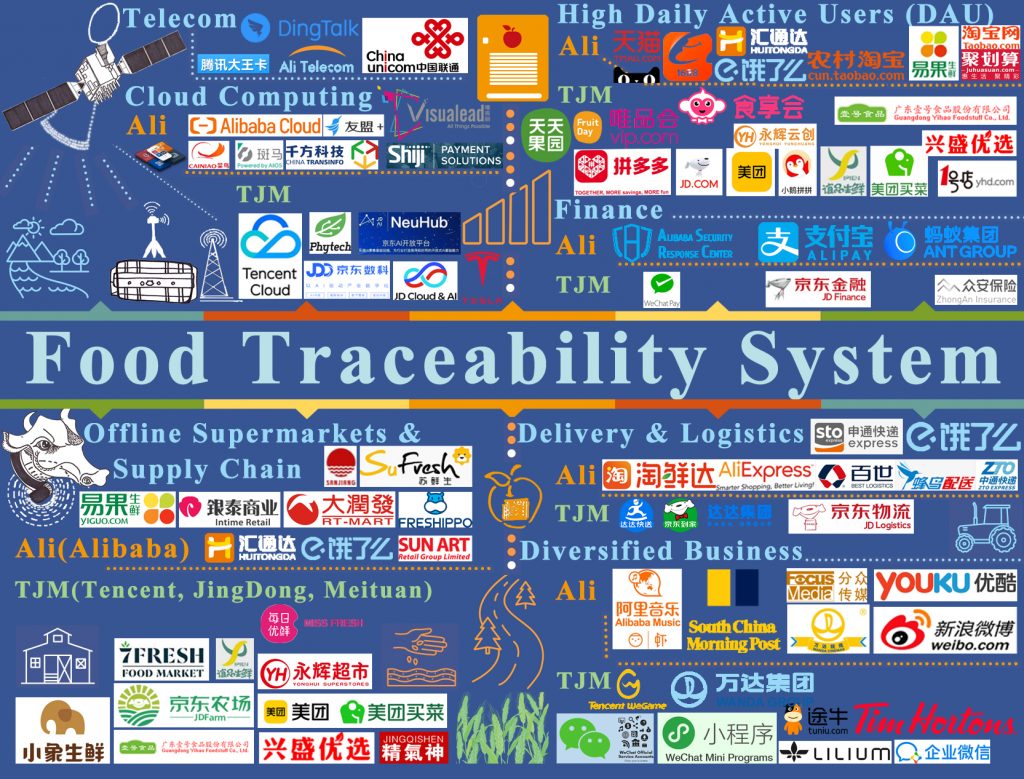

Figure 2 portrays the extent to which the dominant technology companies, Alibaba (Ali), Tencent, JD, and Meituan (TJM), have spread their influence over the various sectors of the food traceability system in China. First and foremost, Ali and the TJM platform ecosystem both invest and collaborate with a Chinese telecom company, China Unicom, to obtain an unfair advantage with high-quality internet connections and better telecom service rates. Furthermore, Ali and the TJM platform ecosystem have invested in information technologies and services like cloud computing. By investing in cloud computing companies like Ali Cloud, the retail technology Shiji, and the intelligent car operating system Banma, Ali has built a solid foundation to amplify traceability technology for commercial applications and actively promote the national code economy. Moreover, Ali and the TJM platform ecosystem have invested in many food traceability platforms with a high level of daily active user rate, like Ele, YiguoShengxian, and Fruit Day.

Ali directs and generates consumer traffic from one site to another, fosters symbiotic relationships, and strengthens the network effect. Their seamless integration also reaches offline activities, from offline supermarkets and supply chains to delivery and logistics systems. The Ali and TJM platform ecosystem integrate almost every aspect of the business.

By luring consumers into scanning offline QR codes, Alipay can potentially connect 555 direct procurement sources, 200 supermarket chains with 1700 traceable food items, free half-hour delivery, and traceable robot restaurants, all within the Alibaba ecosystem. Essentially, food traceability systems connect merchants with the consumer through the integrated platform design from online to offline. This model has now expanded beyond the scope of food, replicating the same business model in other sectors and sharing data with other diversified businesses within the same platform ecosystem. For instance, TJM invested in the travel business TunNiu, flying vehicle company Lilium, coffee franchise Tim Hortons, and film producer Wanda. Ali then uses the data collected and consumer traffic in the game industry, mini-program, business WeChat, and WeVideos. It creates an ultimate one-stop, convenient access center with four essential categories: financial, daily needs, travel and transportation, shopping, and entertainment, all embedded in the platform to further their monopoly and make it more robust. In a nutshell, if you came in for the food traceability information, the big technology corporations try to keep you around for four essential needs that they also own.

The ambitious market model promoted in this manner promises to deliver perfect transparency, but so far, it has only magnified information and power asymmetry. Specifically, between urban and rural regions, there is an imbalance in the development of food safety systems. The food safety and quality tests associated with the current traceability system revealed that twelve provinces were below the national average in food safety. The food safety and quality tests also found that most of the food that was turned down by the city and coastal markets (for having failed the essential food quality and safety test) was then sold back to rural regions. More information does not equal more certainty and transparency. And after all, does the average consumer want to—each time they sit down for a meal—read the entire biography of the hen that laid the egg they are about to eat? Or do they typically just need the peace of mind to enjoy their meal without doubt and concern?

Both the Chinese government and Chinese corporations are convinced that there is a need to build a technology-enabled food traceability system as a market solution to this increasing need. They also believe consumers are willing to pay a premium for the excessive details and data generated by the food traceability system. However, not every Chinese citizen can afford the increased premium, and not everyone feels the need to know the entire life story of a hen before feeling safe enough to eat an egg.

Chinese consumers can still buy the conventional egg without an identification code attached to it—for now. But this is only the beginning. The egg is likely just one example of the future of food consumption. Technology corporations are gradually making significant inroads into the food supply chain, from farms to transportation to retail. They are also exporting IoT technology and the accompanying business model to other parts of the world. Food, of course, is not unique in this, as this trend can be seen in other sectors as well, such as the health and insurance industries.

The next time you are about to eat an egg, consider the story one egg can tell, the industry one egg can change, and the impact one egg can make beyond the act of eating.

Discussion Questions

- What are the potential benefits of the Chinese food traceability system? What are the drawbacks?

- Is there anything in Chinese system that the Canadian food traceability system can adopt or avoid?

Additional Resource

Government of Canada. 2020. Traceability: Safe Food for Canadians Regulations.

References

Alibaba. 2020. 2019 annual report. Alibaba Group.

Alibaba. 2021. 2020 annual report. Alibaba Group.

JD. 2020. 2019 annual report. JD.com, Inc.

JD. 2021. 2020 annual report. JD.com, Inc.

Meituan. 2020. 2019 annual report. Meituan Dianping.

Tencent Holdings Limited. 2020. 2019 annual report. Tencent.

- Alibaba, Tencent, JD, and Meituan are among the top thirteen most valuable publicly traded internet companies in the world. Tencent has the highest monthly active user accounts, at 1165 million, and 50 million active merchant accounts among the big four internet companies (Tencent AR, 5). Alibaba has 846 million monthly active user accounts (Alibaba AR, 21). Meituan has 449 million active user accounts (Meituan AR, 2), but JD has 417 million active user accounts and is more involved in the food traceability system than Meituan (JD AR, 10). Tencent holds 17.9% of JD and 20.1% of Meituan, which are considered as operating under the same Tencent platform ecosystem. Collectively they are referred as TJM. To simplify the infographics, in the figures, Alibaba is referred to as Ali. ↵

the combined practices of ensuring that food and food products are free from harmful substances, both chemical and biological; food safety procedures can exist at all stages and within all spaces of food production, transformation, retail, preparation, and consumption.

a software application containing basic, traceable food production and distribution information that is supported by a range of technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain technologies, cloud computing, data analytics, and sensors in the ‘internet of things’; food traceabiltiy apps are embedded in one or many platforms owned by big technology corporations.

the many layers of technology-enabled food information embedded in highly monopolized platforms that are composed of food traceability apps, mini-programs, smart supermarkets, and offline access QR codes.

an economy in which digital technologies, which use computer code, are commercialized and permeate individual and social life.