Perspective: Food and Identity

Kate Gardner Burt

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Use the Dimensions of Personal Identity model to describe how personal identities are shaped.

- Explain ways in which social norms have an impact on perceptions of food.

- Examine how different ways of knowing shape food culture.

- Use self-reflection and critical analysis to examine their own relationship with food and how that relationship effects their personal identity.

Introduction

What we eat—and don’t eat—is influenced by who we are and where we live. Our individual food choices represent multiple layers of our identities, which are situated within our social and physical environment. What we eat is influenced, for example, by what foods are grown or sold in our geographic regions, by what foods our caregivers served when we were infants, and by the foods our friends and family ate while we were growing up. Our food choices are also influenced by our values, wealth, and social trends. The myriad layers of our own identities give unique meaning to food and, collectively, give rise to food culture. Therefore, understanding food culture requires an analysis of one’s own perspective to explicate personal, community, and societal values, assumptions, norms, and biases. Ultimately, to understand food culture and develop cultural humility—the ability to work effectively with individuals whose identity is different from our own—we must develop self-awareness of our own perspectives as well as an awareness of others’ perspectives.

Our perspectives are a manifestation of our upbringing, informed by our unique personal identities and experiences. Over time, they become a lens that has an impact on the way we view the world. As we grow, so too does our worldview. Our lenses are dynamic—they are shaped and reshaped as we gather information from new sources and understand information in new ways. Each individual’s lens is a synthesis of their multilayered personal identity. Personal identities are simultaneously historic and current; they are rooted in our cultural and familial pasts, but shaped by our personal and present conditions.

Our identities are developed (in part) from various sources of information that we receive consciously and subconsciously. Table 1 provides examples of different types of information received from different sources that shape personal identity.

Table 1: Examples of the type and source of information that shapes personal identity

| Information Type | Internal Information Sources | External Information Sources |

|---|---|---|

| implicit | assumptions; biases; values; personality traits | social norms*; policies; practices; media messaging |

| explicit | choices; conscious thinking | familial norms*; news information; research findings |

*Social and familial norms may be implicit or explicit categorically, or vary depending on the norm itself (e.g., some norms may be explicit while others may be implicit)

As a result, identity is shaped in ways that we are and are not aware of. We unconsciously integrate information into our worldview—what we think of as ‘the way the world works’. However, everyone’s world works differently depending on their identity. A person living in India during the early 1800s has a different worldview than a person born and raised in 21st-century Peru. When we add layers of identity to those contexts, understanding individuals’ experiences becomes more complex, because identity is intersectional (that is, identities overlap and have an impact on each other). A cis-gendered, straight male, born to a high social caste in Mumbai (then Bombay), India in the 1800s has a different identity than a transgender female born into an Andean farming family in modern-day Peru.

Those individuals’ experiences also differ because they exist in different social, political, geospatial, and historical contexts. The policies, systems, and structures operating in those contexts advantage (or privilege) some identities but not others. In other words, gender identity only matters because societies have, in general, given men more advantages than women. Deeper than that, cis-gendered men and cis-gendered women experience more privilege than their transgender peers. In contrast, other demographic identities, like eye color, face shape, handedness, and height are not used for social policy making, so they are still identities, albeit relatively innocuous ones. Ultimately, identities and the social structures in which an individual lives determine the way their world works and the information they come to know.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge— how we know what we know—and epistemological investigation helps us distinguish beliefs from opinions. As investigators, we try to be objective, but in reality, we are not unbiased observers. What we know—or what we think we know—is subject to interpretation, to our interpretation through the lens of our personal identities. We must therefore understand our personal identities in order to distinguish our perspective and how it has an impact on our perceptions. Since our knowledge of food is based on the ways we come to know things, it is up to each of us to better understand ourselves.

What is “knowing”?

What we know is influenced by our personal identities, and our identities become a lens through which we consume and process information. Information may fall into four categories[1]:

- Facts are evidence-based verifiable information, built upon objective reasoning and rooted in science.

- Opinions, or judgements based on facts, are formed in a genuine attempt to draw a conclusion from facts. It is possible to come to different conclusions using the same facts.

- Beliefs are convictions based on cultural or personal faith, morality, or values. In contrast to opinions, beliefs are not necessarily fact-based.

- Prejudices are opinions based on insufficient, faulty, or biased information, and can be disproved by facts. Hidden values and assumptions are embedded in prejudices but can be revealed with critical thinking. Bias and stereotypes are forms of prejudice and can be formed consciously or unconsciously.

Information from each of these categories is used to form knowledge. For example, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans are translated to the general public using MyPlate, a visual method of portioning food, promoted as the healthiest way to eat (see Figure 1).[2]

MyPlate recommendations are based on all of the aforementioned categories of knowledge:

- Facts about nutrient composition (e.g., fruits and vegetables contain valuable nutrients).

- Opinions about how to best translate epidemiological research into practice (e.g., fruits and vegetables should comprise half of one’s intake).

- Beliefs about what foods should be on the plate (e.g., dairy should be included at every meal).

- Prejudices in the form of social norms (e.g., using a Euro-centric nine-inch dinner plate is the best way to communicate this information to Americans, who are predominantly white and of European descent).

Critical thinking is therefore necessary to understand nuances leading to a seemingly fact-based conclusion: To be healthy, eat according to MyPlate.

Each way of knowing is important to understand food culture, and it is important to be able to distinguish them. It is also important to understand that each way of knowing informs food culture. For instance, staple foods are usually based on foods that are indigenous to a region (i.e., facts). Using those foods, cultures develop recipes and patterns of eating that produce a pleasant flavor and aroma (i.e., beliefs, based on sense of smell and taste), which result in some benefit (i.e., opinions, based on relationships between food and health or food cookery), and that are rooted in prejudices or biased social stereotypes (i.e., some foods or food practices are condemned while others are valued).

In order to understand the meaning and value of food, it is necessary to understand how we have built knowledge about food and meaning. We must explore our personal identities through intentional self-reflection to understand how values, assumptions, and biases impact and shape our lens and perspective.[3]

How Personal Identity Shapes Knowledge

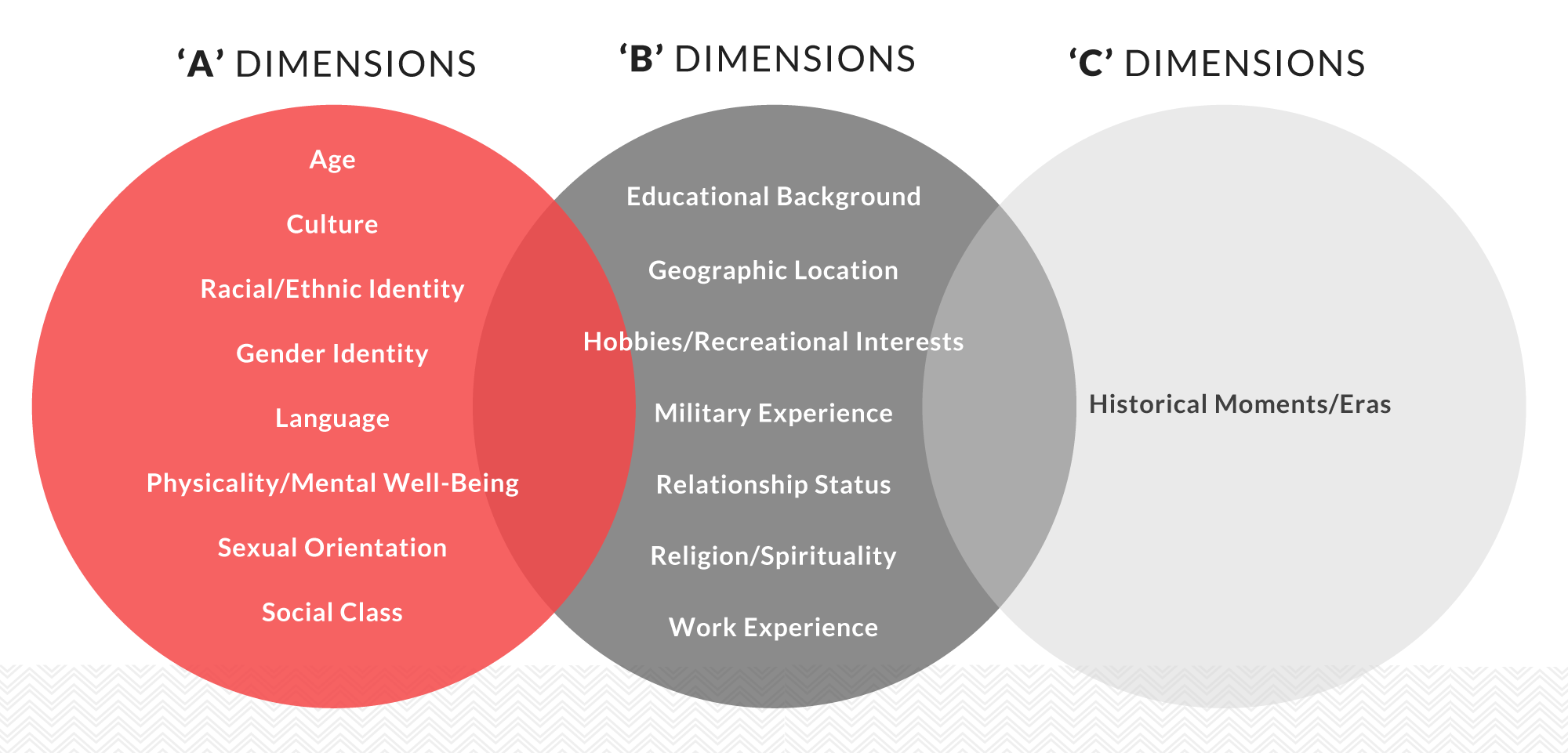

The Dimensions of Personal Identity model (Figure 2) can be used to see ourselves or others clearly because it breaks down how facets of our identities interact to shape who we are and what we know.[4]

There are three dimensions of personal identity:

- Dimension A: visible characteristics you are born with or into, making these characteristics “fixed” or unchangeable. They include age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, culture, language, and social class. These characteristics are the basis for developing assumptions and biases, which can lead to stereotyping and prejudice.[5]

- Dimension B: characteristics that are not always visible. They include personal attributes such as geographic location, educational attainment, marital status, parental status, employment status, hobbies or personal interests, military experience, and religion. Often, individuals exert some control or choice about characteristics in Dimension B (e.g., military service is not always a choice but it can be in some cases).

- Dimension C: the historical, social, political, and cultural context that shape individuals and societies. These characteristics shed light on how our individual or cultural experiences differ by revealing norms, assumptions, and values that influence personal identity.

The “choices” defining an individual’s Dimension B attributes depend largely on Dimension C. The “choices” an individual has only exist within a narrow range of possibilities. For instance, women did not not always have the freedom to choose to be employed; having that choice depended on the era during which they lived. In essence, Dimension B represents the “consequences” of the A and C dimensions. The choices individuals make (B Dimension) are influenced by visible characteristics of Dimension A and the historical, political, and sociocultural context of Dimension C.

To better understand how our identities overlap, intersect, and have an impact on how we are perceived and treated by others, guided group activities like the Personal[6] and Social[7] Identity Wheels or self-guided programs like the Supporting Equitable Dietetics Education Self Study[8] can be used. These toolkits are designed to make relationships between identity, power, and marginalization explicit. In essence, they assert that certain identities are more or less visible at times in a social context. These tools can also reveal how the identities that are most important to an individual may not be view as most important by society at large. Ultimately, because identities have an impact on the experiences individuals have, understanding identity is a critical aspect of understanding worldview.

How Personal Identity Shapes Cultural Knowledge

Though the development of our personal identities is unique, many commonalities exist between individuals who share characteristics. Those commonalities, or collective identities, give rise to social groups. Shared collective identity through social groups, group norms, and values become the basis for cultural identity and knowledge. Though many social groups exist, groups with the most social power and status become dominant. (Often, it is the ‘majority’ group, though not always.) Dominant social groups tend to dictate cultural norms, values, and assumptions, which become interwoven into the structure of society. Ultimately, there becomes a collective perspective that dominates and dictates meaning within a culture. Members who identify with the dominant group typically benefit from the dominant group’s policies and practices, while others do not—a condition called privilege.[9] Privilege is important to understanding one’s relative position in society and how others, who don’t identify with a dominant group, may have similar life circumstances but different experiences.

When we examine social identity using this framework, we see how the dominant group dictates norms and practices. For instance, the use of cutlery, chopsticks, or eating with one’s hands differs regionally across the world, depending on the dominant group’s norms and values. Western societies use cutlery because the dominant group is white European and, historically, white Europeans believe that using cutlery is more refined.[10] With this assertion, however, we see the biased, covert ways that social power is maintained: deeming other (non-European) practices as less refined subjugates the people who follow those practices. Understanding collective identity and dominant group norms is thus important to understanding the meaning of food.

Using Perspective to Make Meaning of Food

Critical analysis is used to understand individual and social phenomena. This section includes three questions that serve as examples of how to apply critical thinking to understanding the meaning of food.

1. How have some cuisines become known as ‘ethnic’ and others are known as ‘expensive’?

What the average U.S. adult is willing to pay for a particular food item is not objectively calculated. If it were, the cost of ingredients and labor would directly correlate with the price of food. Instead, the price of food—particularly restaurant food—is based on something entirely subjective.

The amount of money one is willing to pay for food is directly related to the perception of the culture producing that food.[11] ‘Expensive’ food—or food that people are willing to pay a high price for—is generally produced by cultural groups that are highly regarded by U.S. adults. In contrast, ‘ethnic’ food is often attributed to cultures’ whose prestige or reputation is not as well regarded. The dominant group of U.S. adults, who are white and of European descent, have constructed a social hierarchy based on beliefs and prejudices about others.

For instance, Chinese food is often deemed ‘ethnic’, whereas Italian food is considered expensive and elegant. Yet, both cuisines have dishes based on noodles, with a sauce, and chopped or minced ingredients. They are, on paper, very similar. The price difference between the foods is based on how each culture is perceived. Italian immigrants, once targets of discrimination, gained social capital and respect in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[12] In contrast, Chinese immigrants were subject to an overtly racist immigration ban (the Chinese Exclusion Act) and other forms of stereotyping and discrimination.[13] The dominant group of white U.S. adults perceived Italians to be of greater social rank, leading to a willingness to pay more for food that was perceived to be better.

2. What criteria are used to determine if a dish is “authentic”?

Whether or not a recipe or dish is culturally authentic is more commonly determined by consumers than it is by members of the culture the dish represents. Perceived authenticity is subjective and often an oversimplification of complex cultural underpinnings. Some might consider a dish authentic if it is based on indigenous ingredients and prepared in a way that has been done for many generations. Others might consider a dish authentic if it is frequently consumed in a particular place. These limited definitions fail to capture cultural nuances. The exact ingredients used, the preparation method, the proportion of different ingredients all vary across regions and even within neighborhoods.

Dominant group thinking defines what we know as authentic. The social context includes stereotypes and perceptions of other cultures, and it also includes other influences, like food marketing through gastrodiplomacy. Gastrodiplomacy is a coordinated effort by a nation to use food to promote their culture.[14] As a result, gastrodiplomacy campaigns communicate cultural attributes and values. Thailand, for instance, developed a cultural diplomacy program with a marketing strategy that requires overseas restaurants to be open for at least five days per week for a year, accept credit cards, have at least six Thai dishes on the menu, employ Thai chefs with Thai cooking training, and use materials and equipment from Thailand. It is clear that a goal of the Thai gastrodiplomacy program is to ensure that Thai restaurants abroad communicate similarities about Thai food to consumers. Dishes in restaurants represent only a sliver of authentic Thai cuisine: it is the cuisine that trained chefs prepare, whereas many other authentic examples are prepared in private households. There is not one single version of authentic pad Thai, despite what the gastrodiplomacy program communicates.

3. How does the socio-political environment have an impact on our perceived value of foods?

The perception of foods from specific cultures are not free from the dominant group’s economic and political values. The use of food labels, for example, including how or why a particular food is labeled, varies across nations. In the U.S., food labeling about origin is based on capitalistic notions of ownership through the use of trademarks.[15] In other words, the name of a regional food is attributable and reserved only for the trademark owner; it does not indicate quality. Trademarks are restrictive and relatively expensive for small farmers, serving to carve out rights for businesses and restrict the market. An example of a trademarked name is “Idaho Potatoes.”[16] An Idaho grower using a label that indicates that their potatoes are Idaho Potatoes, but who is not certified by the Idaho Potato Commission, may be subject to a lawsuit.

Geographic indication labels, common in Europe, are based on different values and qualities, such as terroir. Terroir is generally understood as the set of local attributes (including soil chemistry, climate, other environmental factors, and human practice) that impart a distinct set of flavors to the food produced in a given region. It is an indicator of quality, taste, and other desirable attributes. A geographic indication label is not owned by any person or entity, and in can be used by anyone in the region to which it applies, provided they follow certain practices and are certified by regulatory agencies.

While consumers may be unaware of what a given label means, the value of a food product may be related to its commodification (for some people) or cultural pride (for others). Clarifying these differences and understanding how such values are embedded in food culture helps us understand the meaning of foods in various contexts and settings.

Conclusion

In order to understand the meaning of food, we need to understand our own lens—our personal, community, and societal values, assumptions, norms, and biases. Understanding that lens through critical analysis can enhance self-awareness and reflectively examine what is embedded in our own meanings of food. Conducting a self-analysis through the Dimensions of Personal Identity Model or other tools can be helpful in developing an understanding of our individual identity and values, how we are each shaped into the people we are, and our relative position in society (e.g., the degree to which we experience privilege or marginalization). It is important to understand our own biases, through critical reflection or implict bias assessments (many of which are freely available online).

Assessing our own identities and biases can help facilitate an understanding of other cultures’ food because it helps differentiate among facts, beliefs, opinions, and prejudices. Understanding others’ food culture from their perspective, rather than our own, not only helps in understanding the meaning of food for others, it makes each person more culturally humble and able to authentically engage in the world.

Discussion Questions

- Consider the Dimensions of Personal Identity model again. How does your identity shape the meaning of food for you?

- When a dominant social group dictates what “authentic food” looks like in another culture, what are the potential impacts and on whom?

- What is the relationship between cultural humility and empathy? Is either (or are both) required to understand diverse food cultures?

Additional Resources

- Harvard Implicit Association Tests

- How Privileged Are You? (Buzzfeed quiz.)

References

Arredondo, P. 2018. “Dimensions of Personal Identity in the Workplace.” Arredondo Advisory Group (blog), November 7, 2018.

Arredondo, P., R. Toporek, S.P. Brown, J. Sanchez, D.C. Locke, J. Sanchez, and H. Stadler. 1996. “Operationalization of the Multicultural Counseling Competencies.” Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 24, (1): 42–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.1996.tb00288.x.

Burt, K.G. 2020. A Primer on Privilege in Dietetics and Nutrition. EatRightProTV: FNCE 2020 Learning Lounge. Chicago, IL: The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Burt, K.G. 2022. “The Whiteness of the Mediterranean Diet: A Historical, Sociopolitical, and Dietary Analysis Using Critical Race Theory.” Journal of Critical Dietetics.

“Epistemology.” 2021. In Oxford University Press.

Fowler, H.R., and J.E. Aaron. 2011. The Little, Brown Handbook. 12th ed. Boston: Pearson

Goldsmith, S. 2012. “The Rise of the Fork.” Slate, June 20, 2012.

Hodge, D.R. 2018. “Spiritual Competence: What It Is, Why It Is Necessary, and How to Develop It.” Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 27 (2): 124–39.

“Idaho Potato Commission.” Accessed January 25, 2021.

Josling, T. 2006. “The War on Terroir: Geographical Indications as a Transatlantic Trade Conflict.” Journal of Agricultural Economics 57 (3): 337–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2006.00075.x.

“MyPlate | U.S. Department of Agriculture.” Accessed May 6, 2021.

University of Michigan. 2021 “Personal Identity Wheel – Inclusive Teaching.”

Ray, Krishnendu. 2016. The Ethnic Restaurateur. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Rude, Emelyn. 2016. “A Very Brief History of Chinese Food in America.” Time Magazine, February 8, 2016.

University of Michigan. 2021. “Social Identity Wheel – Inclusive Teaching.”

“Supporting Equitable Dietetics Education Self Study.” 2021. Diversify Dietetics.

Yeager, K.A., and S. Bauer-Wu. 2013. “Cultural Humility: Essential Foundation for Clinical Researchers.” Applied Nursing Research 26 (4): 251–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008.

Zhang, J. 2015. “The Foods of the Worlds: Mapping and Comparing Contemporary Gastrodiplomacy Campaigns.” International Journal of Communication 9: 568–91.

- Fowler & Aaron 2011. ↵

- MyPlate | U.S. Department of Agriculture 2021. ↵

- Arredondo et al. 1996; Yeager & Bauer-Wu 2013; Hodge 2018. ↵

- Arredondo et al. 1996. ↵

- Arredondo 2018. ↵

- Personal Identity Wheel – Inclusive Teaching 2021. ↵

- Social Identity Wheel – Inclusive Teaching 2021. ↵

- Supporting Equitable Dietetics Education Self Study 2021. ↵

- Burt 2020; Goldsmith 2012. ↵

- Goldsmith 2012. ↵

- Ray 2016. ↵

- Burt n.d. ↵

- Rude 2016. ↵

- Zhang 2015. ↵

- Josling 2006. ↵

- Idaho Potato Commission 2021. ↵

an ongoing process, rather than a state of being, that requires the development of self-awareness about personal and cultural identity, as well as knowledge about others.

the relationship among the multiple identities, policies, systems, and structures that have an impact on an individual’s relative position in society

a branch of philosophy focused on the theory of knowledge, specifically its nature and origin; the processes and structures of making knowledge.

understanding of the history, social context, and values of a cultural group.

unearned social advantage that may influence an individual’s behaviours in ways that become problematic for those without privilege; often invisible to those that have it.

a coordinated effort by a nation to use food to promote its national identity and culture.

a marker or tool used to identify the geographic origin of a product.