Perspective: Food Allergies

Janis Goldie

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Explain the basic aspects of food allergies and their prevalence as a public health issue.

- Describe how food allergies are an important issue of consideration in the broader context of Food Studies.

- Identify elements of the impact and experience of those living with food allergies.

Introduction

What did you eat for lunch today? A sandwich? Perhaps some bannock or curry? Maybe a sushi roll or a taco or a slice of pizza? Did you think about the ingredients? How the food was prepared? What oil or condiment was used? Did you consider that eating your lunch might harm you—harm you so severely that you would need immediate medical attention and, if not treated promptly, could even die? If these questions aren’t at the top of your mind before lunch—or every time you eat—then you probably don’t live with a food allergy.

Food allergies occur when the immune system does not recognize a food as safe and responds with an allergic reaction.[1] A serious reaction, anaphylaxis, can manifest as a number of different body-system effects, such as respiratory (trouble breathing, chest pain, or throat tightness), skin (hives or swelling of the face or lips or tongue), gastrointestinal (nausea or vomiting), or cardiovascular (dizziness or fainting), among others. While reactions can range in severity, a food allergy is a chronic health condition, requiring ongoing medical attention and limiting the daily activities of those afflicted.

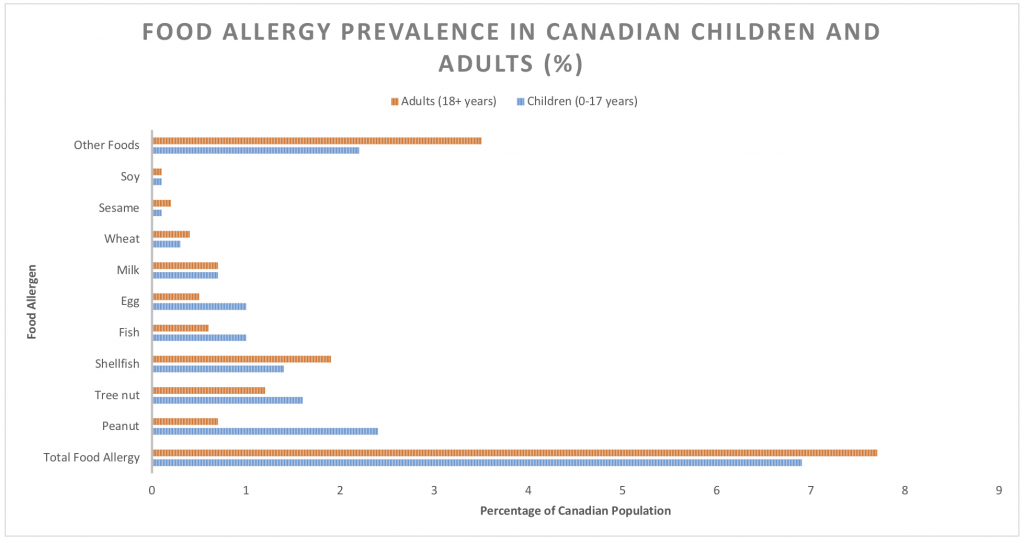

Roughly 2.6 million Canadians are affected by food allergies that can be deadly if treatment is delayed.[2] In Canada, 7.7 percent of adults and 6.9 percent of children under the age of 18 now report having at least one food allergy.[3] Peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, mustard, fish, shellfish, sesame, soy, and wheat are the priority food allergens in Canada and are responsible for the majority of clinical reactions.[4] (See Table 1 below for breakdown of prevalence by age and allergen in Canada.) Food allergies are a serious and growing public health issue in Canada and much of the world. There has been a significant reported rise in food allergies in the past two decades, with up to a 50 percent increase of prevalence for children since 1997.[5] With prevalence at an all-time high[6] and no agreed upon explanation as to the cause and minimal treatment options available for the food allergic, food allergies are cause for concern.[7]

Alongside the increasing prevalence of food allergies, research on the subject has also increased over the last few decades. Living with a food allergy qualifies as a legal disability under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada, including an obligation to accommodate.[8] Those with food allergies are frequently bullied, socially isolated, economically challenged, and experience significant negative outcomes on their quality of life (QoL). In this way, “food allergies not only increase the risk of fatality for those most severely affected, they regularly disrupt life for those diagnosed and their families”.[9] Given that eating is a constant and potentially lethal risk, the study of food allergies presents a unique and important perspective to consider within food studies. Whether examining the issue from a food systems, culture, justice, risk, feminist, or policy lens, the topic of food allergies provides an ample area for future study in the field.[10] In the following section, some of the current findings in the research on food allergies are outlined. I then go on to discuss an area that is receiving greater consideration and research—the communication or discourse of food allergies.

Current Research

The Impact and Experiences of Food Allergies

The majority of the research on food allergies to date is biomedical. Biomedical studies examine issues such as current diagnosis options, prevention, treatment, and management strategies, as well as the epidemiology of food allergies and their prevalence.[11] In contrast, social science research on food allergies has focused on the experiences and effects of living with food allergies. For example, recent studies on the economic costs associated with food allergies have found that the overall economic burden is substantial, both for those with food allergies as well as for healthcare systems.[12] In Canada, families with a member who has a food allergy reported higher direct annual costs of just less than $2400 (on average), largely attributed to increased spending on groceries and restaurant meals. Food-allergic families also spent more travelling to medical appointments and on medications compared to families without a food allergy.[13] While healthcare costs in Canada related to food allergies are only beginning to be tracked, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) reported that between 2007 and 2014, the total number of visits to the emergency departments for anaphylaxis and allergy rose from 69,691 to 84,855 in Alberta and Ontario alone.[14] Other studies have examined billing fees from physicians for common allergy tests across Canada and have found that costs vary widely depending on the service and province.[15]

Beyond the economic effects of living with a food allergy, there has also been a significant focus on the effects on QoL and the lived experiences of the food allergic as well as their caregivers. This research includes examinations of the psychosocial and mental health impacts of living with food allergies, as well as daily management and health-related measures.[16]. These studies show how all areas of life can be affected by food allergies—including emotional, physical, and social—for the food allergic and their family members. Everything from grocery shopping, meal preparation, school attendance, family and social activities, as well as social skills can be impacted. In addition, the effect on caretakers of children with food allergies, as well as the children themselves, can result in high levels of emotional distress and anxiety. Caregivers feel sadness, anger, guilt, worry, and uncertainty about food allergies in their children, and that their distress becomes worse if they have fewer emotional resources, younger children, and/or children with behavioural problems. [17] In addition to the effects on mental health, there are notable psychosocial effects. Living with a food allergy results in significant instances of social isolation, such as not being able to attend or participate in workplace, friend or family functions, restaurant outings, or even travel opportunities, which further affects QoL.[18] For children, not being able to eat what others are eating, or even needing to eat alone, can be particularly challenging in social settings such as schools, parties, and sports events. In addition, bullying is a noted problem for children with food allergies. Anywhere from 16 to 32 percent of children or teens report having been teased or bullied because of their food allergy, often leading to negative emotional/psychological impacts such as sadness, depression, and decreased QofL.[19] Other studies note the stigma surrounding food allergies and the challenges that go along with the consistent self-identification that management of a chronic health condition necessitates.[20]

With regard to vulnerable groups, research has indicated that education, socioeconomic status, and race can affect the experiences and management of food allergies. For example, lower-income individuals in Ontario with food allergies reported difficulty obtaining safe food and medications due to medical misinformation, having to use food banks, and/or general financial barriers.[21] Other studies have found that Caucasian children and those with higher income are more frequently provided a diagnosis than other children,[22] while Aboriginal children have low rates of diagnosis and treatment for their food allergies as well as significant disparities in food allergy management related to health–care access.[23]

Various other studies on food allergies have examined risk perception as well as risk-taking behaviors, such as the conscious risks teenagers with food allergies are willing to take (trying food without knowing the ingredients, not having their EpiPens on hand, etc.), in addition to management strategies and practices in schools and policies, to name just a few areas.[24] In all, the study of food allergies is a burgeoning area of focus with many facets.

Food and Communication: The Discourse of Food Allergies

In food studies, food is understood to be much more than just a means of survival. Food is sustenance, but it is also “a symbol, a product, a ritual object, an identity badge, an object of guilt, a political tool, even a kind of money.”[25] As Koç, Sumner, and Winson argue, “What we eat, how we eat, when we eat, and with whom we eat reflect the complexity of our social, economic, political, cultural, and environmental relations with food”.[26] Food has much meaning. As such, the combination of a communication studies approach and a food studies approach (both fields emphasize interdisciplinarity and a critical perspective) is a natural fit.

Connecting food and communication is a fairly recent move.[27] The study of communication “is concerned with understanding the ways in which humans share verbal and nonverbal symbols, the meanings of the shared symbols, and the consequences of the sharing.”[28] Because food is a nonverbal symbol in so many ways, unpacking the meanings that we have around food and the consequences of those meanings is crucial to understanding food. Food is also a code, much like language, in that it expresses patterns of social relationships, can be performative, and is directly linked to both ritual and culture.[29] In all of these ways, we “use food to communicate with others and as a means of demonstrating personal identity, group affiliation and disassociation, and other social categories, such as socioeconomic class” so that “food functions symbolically as a communicative practice by which we create, manage and share meanings with others.”[30] We use food in the construction and communication of our own personal identities, in our group associations, and our ability to share and discuss food across a wide variety of social sites and situations. Importantly, our communication about food, which can be referred to as our food discourse, “operates as important ‘sites of struggle’ with significant social and political implications.”[31] Discourses around the local food movement, organic food, or dietary practices such as veganism, for example, all point to social and political implications such as changes in production and consumption behaviours, investments in economic resources, and government policies.[32]

When we understand that not just food and the ways we communicate about food matter economically, politically, and socially, we start to ask questions about the ways issues such as food allergies are represented in talk, text, and media culture more broadly. We also start pay more attention to the implicit and explicit meaning of discourses around food allergies, and what they mean for how we develop resources and supports, approach treatments, management practices, policies, etc. While there is a great deal of research on food allergies, the focus on the various discourses of food allergies is only beginning to receive more attention.

Examining how we communicate about food allergies can be undertaken in various discursive sites of text and talk across various contexts. A few studies have begun to examine the discourse of food allergies within sites of media culture. For example, looking at food allergy blogs, Morlacchi has investigated the ways that food-allergy discourse orients the health risk as an individual responsibility, centered on food consumption and choice. Further, she highlights that that responsibility is represented as a gendered one, so that “allergy foodwork is overwhelmingly seen as the responsibility of women as mothers and as providers of food for their families.”[33] Analysis on the framing of food allergy discourse in the news has pointed to the way that certain stakeholders frame issues differently. Advocates and affected individuals make moral judgments and suggest remedies, while doctors diagnose the cause of food allergies or frame food policy issues.[34] Others point to the harmful effects of representing food allergies humorously in entertainment media.[35] In a recent piece, for example, two short comedic media representations of food allergies were analyzed: an episode of CBC Television’s Mr. D, in which one of the main characters has an anaphylactic reaction; and a short stand-up skit from the Halifax Comedy Festival about food allergies in wartime.[36] These media artifacts represent food allergies as something to be not taken seriously, even ridiculed. The food allergic are shown as weak and unable to survive or cope with life’s everyday challenges. Further, food allergies are represented as an individual problem—one in which the food allergic is responsible for the problem solely on their own.

These messages matter, because like all discourse circulating in the public domain, they can inform our broader beliefs and behaviours, especially when certain representations persist and dominate. Its pervasiveness in North America as a cultural-orientation machine means that media culture offers much social instruction about who we are and what our norms and values are in a society. The ways that food allergies are presented in our popular media such as comic books[37], news or social media[38] or entertainment texts, can thus influence how we feel, think about, or react to food allergies in our lives. If the messages we hear about food allergies on television, for example, tell us that people with food allergies are weak and that food allergies are not an issue to take seriously, then it might relate to the policies that are created for schools or the real-world bullying that exists for the food allergic.

In all, while the study of the discourses of food allergies needs much more attention, it is an important step in the research on food allergies more generally. When we tie the research on the experiences of those living with, or caring for, the food allergic with research into the way we talk about, and thus understand food allergies, we are much better positioned to provide valuable and meaningful social impact. We must first assess how we understand the meanings behind food allergies in our cultures if we are to come to any sort of health or policy solutions.

Conclusion

The issue of food allergies is an important area of consideration within the broader field of food studies because of its increasing prevalence and the impacts it has on the daily lives of those affected. The study of food allergies also provides a valuable opportunity to examine an area of discourse of food—in which the meanings imbued within a wide variety of talk and text construct and cement our understandings of disease, management strategies, support systems, and policies. We are used to thinking about food as a source of nourishment and identity, as well as for enjoyment and pleasure. But when the food one consumes poses a constant, everyday risk to one’s life, there are very different meanings imbued within it. Understanding the different ways that food means is an important endeavour to continue to build on in the work of food studies.

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important to connect food discourse to the broader field of food studies? Why do our meanings and language about food matter?

- Why do you think the research on food allergies has been slow to examine the communication around this health issue?

- What representations have you seen of food allergies in media culture? Do you recall any scenes in popular films or television series in which a food allergy episode or reaction occurs? If so, what happened? How was the reaction portrayed? How was the person experiencing the reaction portrayed? What meanings about food allergies were constructed? Do these align with the experiences indicated by the academic research?

Additional Resources

National Film Board, Sabrina’s Law, 2007, documentary available for free online streaming.

References

Abo, M.M., M.D. Slater, and P. Jain. 2017. “Using Health Conditions for Laughs and Health Policy Support: The Case of Food Allergies.” Health Communication 32 (7): 803–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1172292.

Abrams, E.M., E. Simons, J. Gerdts, O. Nazarko, B. Povolo, and J.L.P. Protudjer. 2020. “‘I Want to Really Crack This Nut’: An Analysis of Parent-Perceived Policy Needs Surrounding Food Allergy.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 1194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09309-w.

Abrams, E.M., E. Simons, L. Roos, K. Hurst, and J.L.P. Protudjer. 2020. “Qualitative Analysis of Perceived Impacts on Childhood Food Allergy on Caregiver Mental Health and Lifestyle.” Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 124 (6): 594–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2020.02.016.

Clarke, A.E., S.J. Elliott, Y. St. Pierre, Lianne Soller, Sebastien La Vieille, and Moshe Ben-Shoshan. 2020. “Temporal Trends in Prevalence of Food Allergy in Canada.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 8 (4): 1428-1430.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.021.

Cummings, A.J., R.C. Knibb, Michel Erlewyn‐Lajeunesse, Rosemary M. King, Graham Roberts, and Jane S. A. Lucas. 2010. “Management of Nut Allergy Influences Quality of Life and Anxiety in Children and Their Mothers.” Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 21 (4p1): 586–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00975.x.

de Silva, D., S. Halken, C. Singh, A. Muraro, E. Angier, S. Arasi, H. Arshad, et al. 2020. “Preventing Food Allergy in Infancy and Childhood: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials.” Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 31 (7): 813–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13273.

Desrochers, P. 2016. “Lies, Damned Lies, and Locavorism: Bringing Some Truth in Advertising to the Canadian Local Food Debate.” In Food Promotion, Consumption and Controversy: How Canadians Communicate VI, edited by Charlene Elliott. Athabasca, AB: Athabasca University Press: 229–250.

Derkatch, C. and P. Spoel. 2017. Public Health Promotion of ‘Local Food’: Constituting the self-governing citizen-consumer. Health 2 (2): 154–170.

Dixon, J., S.J. Elliott, and A.E. Clarke. 2016. “‘Exploring Knowledge-User Experiences in Integrated Knowledge Translation: A Biomedical Investigation of the Causes and Consequences of Food Allergy.’” Research Involvement and Engagement 2 (1): 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0043-x.

Elliott, S., and F. Cardwell. 2018. “What about the Other 50 Percent of the Canadian Population? Food Allergies Ignored in National Policy Plan.” Canadian Food Studies / La Revue Canadienne Des Études Sur l’alimentation 5 (3): 285–89. https://doi.org/10.15353/cfs-rcea.v5i3.326.

“Estimated Food Allergy Prevalence among all Canadians.” 2017. AllerGen.

Fong, A.T., C.H.Katelaris, and B. Wainstein. 2017. “Bullying and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Food Allergy: Bullying with Food Allergy.” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 53 (7): 630–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13570.

Foong, R.-X., J.A. Dantzer, R.A. Wood, and A.F. Santos. 2021. “Improving Diagnostic Accuracy in Food Allergy.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 9 (1): 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.037.

Goldie, J.L. 2019. “The ‘Funny’ Thing About Food Allergies….in Canadian Media.” In The Spaces and Places of Canadian Popular Culture, edited by Victoria Kannen and Neil Shyminsky, 318–27. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press.

Golding, M.A., E. Simons, E.M. Abrams, J. Gerdts, and J.L.P. Protudjer. 2021. “The Excess Costs of Childhood Food Allergy on Canadian Families: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 17(1): 1-11.

Greene, C.P., and J.M. Cramer. 2011. “Beyond Mere Sustenance: Food as Communication/Communication as Food.” In Food as Communication: Communication as Food, edited by Janet M. Cramer, Carlnita P. Greene, and Lynn M. Walters, ix–xix. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Greenebaum, J. 2012. Veganism, Identity and the Quest for Authenticity. Food, Culture & Society 15 (1): 129-144.

Gupta, R.S., E.E. Springston, M.R. Warrier, B. Smith, R. Kumar, J. Pongracic, and J.L. Holl. 2011. “The Prevalence, Severity, and Distribution of Childhood Food Allergy in the United States.” Pediatrics 128 (1): e9–17. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0204.

Gupta, R., D. Holdford, L. Bilaver, A. Dyer, J.L. Holl, and David Meltzer. 2013. “The Economic Impact of Childhood Food Allergy in the United States.” JAMA Pediatrics 167 (11): 1026–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2376.

Hamshaw, R.J.T., J. Barnett, and J.S. Lucas. 2017. “Framing the Debate and Taking Positions on Food Allergen Legislation: The 100 Chefs Incident on Social Media.” Health, Risk & Society 19 (3–4): 145–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2017.1333088.

Harrington, D.W., K. Wilson, S.J. Elliott, and A.E. Clarke. 2013. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Food Allergies in Off-Reserve Aboriginal Children in Canada.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien 57 (4): 431–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2013.12032.x.

Henderson, M.C. 1970. “Food as Communication in American Culture: Today’s Speech: Vol 18, No 3.” Today’s Speech 18 (3): 3–8.

Husain, Z., and R.A. Schwartz. 2013. “Food Allergy Update: More than a Peanut of a Problem.” International Journal of Dermatology 52 (3): 286–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05603.x.

Information Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2015. “Anaphylaxis and Allergy in the Emergency Department.”

Jackson, K.D., L.D. Howie, and O.J. Akinbami. 2013. Trends in Allergic Conditions Among Children: United States, 1997-2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

Kamdar, T.A., S. Peterson, C.H. Lau, C.A. Saltoun, R.S. Gupta, and P.J. Bryce. 2015. “Prevalence and Characteristics of Adult-Onset Food Allergy.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. In Practice 3 (1): 114-5.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2014.07.007.

Koç, M., J. Sumner, and A. Winson, eds. 2017. Crtical Perspectives in Food Studies. Second. Don Mills, ON: Oxford.

Lizie, ArtAhur. 2014. “Food and Communication.” In Routledge International Handbook of Food Studies, edited by Ken Albala, 27–38. New York, NY: Routledge.

McNicol, S. and S. Weaver. 2013. “‘Dude! You Mean You’ve Never Eaten a Peanut Butter and Jelly Sandwich?!?’ Nut Allergy as Stigma in Comic Books.” Health Communication 28 (3): 217–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.669671.

Miller, J., A.C. Blackman, H.T. Wang, S.Anvari, M. Joseph, C.M. Davis, K.A. Staggers, and Aikaterini Anagnostou. 2020. “Quality of Life in Food Allergic Children: Results from 174 Quality-of-Life Patient Questionnaires.” Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 124 (4): 379–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2019.12.021.

Minaker, L.M., S.J. Elliott, and A. Clarke. 2014. “Exploring Low-Income Families’ Financial Barriers to Food Allergy Management and Treatment.” Journal of Allergy (February): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/160363.

Morlacchi, P. n.d. “Foodwork as Re-Articulation of Women’s in/Visible Work: A Study of Food Allergy Blogs.” Gender, Work & Organization. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12600.

Murdoch, B., E.M. Adams, and T. Caulfield. 2018. “The Law of Food Allergy and Accommodation in Canadian Schools.” Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 14 (1): 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0273-6.

Nettleton, S., B. Woods, R. Burrows, and A. Kerr. 2010. “Experiencing Food Allergy and Food Intolerance: An Analysis of Lay Accounts.” Sociology 44 (2): 289–305.

Nwaru, B.I., L. Hickstein, S.S. Panesar, A. Muraro, T. Werfel, V. Cardona, A.E.J. Dubois, et al. 2014. “The Epidemiology of Food Allergy in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Allergy 69 (1): 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12305.

Pitchforth, E., S. Weaver, J. Willars, E. Wawrzkowicz, D. Luyt, and M. Dixon-Woods. 2011. “A Qualitative Study of Families of a Child with a Nut Allergy.” Chronic Illness 7 (4): 255–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395311411591.

Protudjer, J., L. Penner, L. Soller, E.M. Abrams, and E.S. Chan. 2020. “Billing Fees for Various Common Allergy Tests Vary Widely across Canada.” Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 16 (28): 1–6.

Rachul, C., and T. Caulfield. 2011. “Food Allergy Policy and the Popular Press: Perspectives From Canadian Newspapers.” Journal of Asthma & Allergy Educators 2 (6): 282–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150129711410691.

Ravid, N.L., R.A. Annunziato, M.A. Ambrose, K. Chuang, C. Mullarkey, S.H. Sicherer, E. Shemesh, and A.L. Cox. 2012. “Mental Health and Quality-of-Life Concerns Related to the Burden of Food Allergy.” Immunology and Allergy Clinics 32 (1): 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2011.11.005.

Sauer, K., E. Patten, K. Roberts, and M. Schartz. 2018. “Management of Food Allergies in Schools.” Journal of Child Nutrition & Management 42 (2).

Shaker, M.S., J. Schwartz, and M. Ferguson. 2017. “An Update on the Impact of Food Allergy on Anxiety and Quality of Life.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics 29 (4): 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000509.

Sicherer, S.H., and H.A. Sampson. 2018. “Food Allergy: A Review and Update on Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 141 (1): 41-58.

Soller, L., M. Ben-Shoshan, D.W. Harrington, M. Knoll, J. Fragapane, L. Joseph, Y. St. Pierre, et al. 2015. “Prevalence and Predictors of Food Allergy in Canada: A Focus on Vulnerable Populations.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 3 (1): 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2014.06.009.

Warren, C.M., J. Jiang, and R.S. Gupta. 2020. “Epidemiology and Burden of Food Allergy.” Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 20 (2): 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-0898-7.

Warren, C.M., A.A. Dyer, A.K. Otto, B.M. Smith, K. Kauke, C. Dinakar, and R.S. Gupta. 2017. “Food Allergy–Related Risk-Taking and Management Behaviors Among Adolescents and Young Adults.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 5 (2): 381-390.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.12.012.

“WHOQOL – Measuring Quality of Life| The World Health Organization.” n.d. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol.

Williams, N.A., G.R. Parra, and T.D. Elkin. 2009. “Subjective Distress and Emotional Resources in Parents of Children With Food Allergy.” Children’s Health Care 38 (3): 213–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739610903038792.

Zhen, W. 2019. Food Studies: A Hands-On Guide. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nettleton 2010. ↵

- AllerGen 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Husain & Schwartz 2013. ↵

- Jackson et al. 2013. ↵

- Sicherer & Sampson 2018. ↵

- Clarke et al. 2020; Soller et al. 2015; Kamdar et al. 2015. ↵

- Murdoch et al. 2018. ↵

- Elliott & Cardwell. 2018. ↵

- Zhen 2019. ↵

- Foong et al. 2021; Dixon et al. 2016; Silvaet al. 2020; Nwaruet al. 2014; Warren et al. 2020. ↵

- Gupta et al. 2013. ↵

- Golding et al. 2021. ↵

- Information Canadian Institute for Health Information 2015. ↵

- Protudjer et al. 2020. ↵

- Cummings et al. 2010; Shaker et al. 2017; Miller,et al. 2020. ↵

- Williams et al. 2009; Abrams et al. 2020. ↵

- Ravidet al. 2012. ↵

- Fong et al. 2017. ↵

- Pitchfort 2011. ↵

- Minaker et al. 2014. ↵

- Gupta et al. 2011. ↵

- Harrington et al. 2013. ↵

- Warrenet al. 2017; Abramset al. 2020; Sauer et al. 2018. ↵

- Reardon cited in Koç et al. 2017. ↵

- Koç et al. 2017. ↵

- Henderson 1970. ↵

- Lizie 2014. ↵

- Greene & Cramer 2011. ↵

- Ibid, xi. ↵

- Fiske cited in Greene & Cramer 2011. ↵

- Desrochers 2016; Derkatch & Spoel 2017; Greenebaum 2012. ↵

- Morlacchi n.d., 11. ↵

- Harrington et al. 2012; Rachul & Caulfield 2011 ↵

- Abo et al. 2017; Goldie 2019. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- McNicol & Weaver 2013. ↵

- Hamshaw et al. 2017. ↵

a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction.

an individual's perception of how they are doing, relative to others in comparable context and value systems; may include aspects of health, wealth, work, economic and social status, religious beliefs and freedoms, safety, education, and free/leisure time.

talk or text in social and historical context, about any subject, at any time, and in any form, where materializations of meaning or ideology exist.

the creation of a new space of academic investigation through the blending or hybridization of two or more disciplines.

the ways in which mass media, including digital platforms, are integrated within society and culture, producing lasting effects in human interaction; includes processes of mediation in broader cultural discourse.