Perspective: Eating Healthy

Jennifer Brady

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Describe the two divergent paradigms of healthy eating that are central to current nutrition debates.

- Identify and define key concepts for thinking critically about healthy eating.

- Discuss healthy eating as an area of contested meaning that shapes—and is shaped—by power inequities.

Introduction

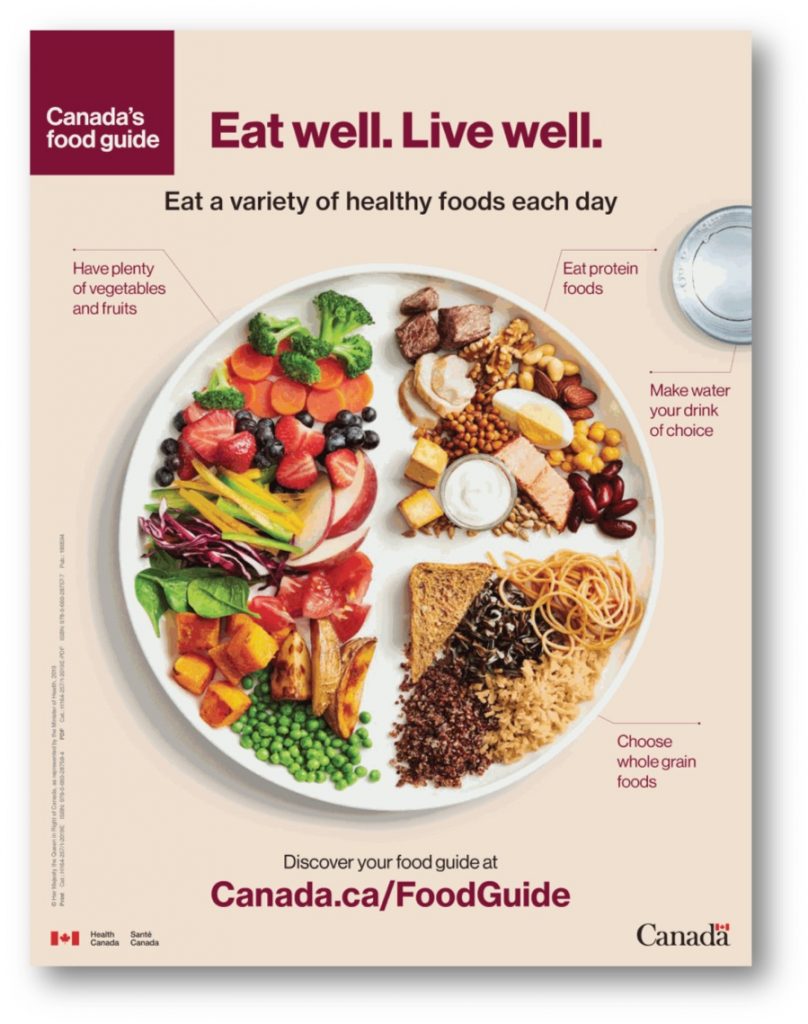

What is healthy eating? For many, the answer to this question seems simple: healthy eating means eating a variety of foods with an emphasis on low-calorie, nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables, fibre-rich whole grains, lean proteins, and unsaturated healthful fats, like plant-based oils. Conversely, healthy eating means avoiding unhealthful foods, which are high in calories, fat, salt, and sugar. This description reflects a mainstream account of healthy eating that is championed by nutrition and health experts, as well as via government-issued tools and policies, such as Canada’s Food Guide. Although the answer to the question “what is healthy eating?” may seem simple, this chapter suggests that it is anything but!

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755–1826), a French politician and lawyer, wrote, “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es.”[1] This phrase is often translated into the well-known idiom, “You are what you eat.” However, a more accurate translation reads, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” In other words, who and what we are, our social, cultural, and spiritual identities, and even our bodies, shape and are shaped by what we eat. If we agree with Brillat-Savarin’s observation—and many do—then it is important to think about another question when thinking about healthy eating: If we tell people what to eat, aren’t we at the same time telling them who we think they should be?

This question is important because it invites consideration of the ways in which defining healthy eating and telling others what to eat is inherently political. That is, the ways in which healthy eating is defined and communicated to diverse populations are not neutral. This includes the people, the knowledge, and the language involved in such communications. Rather, as researchers in the fields of critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics have established, healthy eating is a terrain of competing perspectives that are rooted in diverse forms of knowledge. Said otherwise, healthy eating is intertwined with social and structural inequities in society.

Current debates

An important debate within critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics is about who gets to decide what it means to eat healthy and based on what criteria. Although there are a multitude of views about what healthy eating is, at the core of current debates lie two competing perspectives—or paradigms—each of which present divergent ideas about what healthy eating is, the kinds of knowledge that are important to understanding it, and what it means to tell others what they should and shouldn’t eat to be healthy.

On one side of the debate is a dominant paradigm. A dominant paradigm may be described a set of values and ways of thinking about an issue that becomes so pervasive that the underlying assumptions and approaches to understanding it are seen to be normal and completely natural, and other perspectives and approaches are dismissed as inappropriate or false. On the other side of the debate is a critical paradigm. A critical paradigm also comprises a set of values and ways of thinking about an issue, but it is explicitly concerned with relationships of power. More specifically, a critical paradigm is concerned with the ways in which power inequities form and are perpetuated in society. Hence, the dominant and critical paradigms comprise very different priorities and ways of understanding what it means to eat healthy, and what it means to tell others what to eat. The next two subsections explore each paradigm in more detail.

The Dominant Paradigm

Why, at first glance, does the question “What is healthy eating?” seem so simple? How is it that we all seem to be able to recite a version of healthy eating that approximates the one described at the beginning of this chapter, even though it does not reflect what, how, or why many of us eat? In short, healthy eating is the subject of a dominant paradigm. In other words, healthy eating has come to be defined in ways that reflect a particular set of values, ideas, assumptions, and forms of knowledge that are largely taken for granted. More specifically, the values, ideas, assumptions, and ways knowing that underlie hegemonic nutrition frame healthy eating as something that is best understood as a biophysiological concern, and is therefore most accurately described using science and quantitative measure. That is, the dominant paradigm understands healthy eating through an approach to knowledge known as a positivist epistemology. When viewed through this lens, the criteria used to define healthy eating focus almost exclusively on the quantifiable nutrients contained in single food items, which are determined through scientific analysis. Hence, the answer to the question, “What is healthy eating?” is simply understood as the consumption of foods that are high in health-promoting nutrients and low in nutrients that are seen as harming one’s health.

An example of hegemonic nutrition as the dominant paradigm of healthy eating is Canada’s Food Guide (see Figure 1).[2] Canada’s Food Guide reflects the model of healthy eating that is described at the beginning of this chapter, and that stems from a positivist epistemological approach. In other words, Canada’s Food Guide categorizes and promotes foods based almost exclusively on their nutrient content. For example, fruits and vegetables are grouped and promoted based on their relatively high content of fibre and micronutrients, such as vitamins and antioxidants, versus the number of calories and the amount of fat, sugar, and salt. Likewise, the recommendation to “eat protein foods,” particularly those that are plant-based and unprocessed, is intended to encourage consumption of foods such as fish and legumes, which are high in protein and other health-promoting nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids and fibre, and which are low in calories and saturated fat.

The dominant paradigm of healthy eating and the science of nutrition have led to important discoveries about consuming certain nutrients and avoiding others. This in turn can benefit our health and help to manage and/or reduce our risk of various diseases. But consider this: there is also much about food, eating, and health that the dominant paradigm and nutrition science cannot tell us about healthy eating. To explore this issue, consider how the question “What is healthy eating?” might be answered from the perspective of the critical paradigm.

The Critical Paradigm

In contrast to the dominant paradigm, the critical paradigm draws on a different understanding of what counts as legitimate knowledge, known as interpretive epistemology. An interpretive epistemological approach sees food, eating, and health as being highly contextual, and that insights gained from people’s lived experience are also important to understanding healthy eating. In other words, the critical paradigm sees food, eating, and health—and how we understand these things—as inseparable from the social, cultural, economic, political, historical, and geographic contexts in which they exist. This includes the ways in which food, eating, and health are understood and experienced by people. For example, when viewed from the dominant paradigm, chocolate cake is a high-calorie, nutrient-poor, unhealthful food. Yet when viewed with from the critical paradigm, eating chocolate cake is (for many of us) laden with meanings that connect us to who we are, to our relationships with friends and family, and to important social and cultural rituals like birthdays. Hence, from a critical perspective, what healthy eating is depends on a set of unique circumstances related to who, when, where, why, and how one might be seeking to define healthy eating. The critical paradigm thus implies that understanding healthy eating requires knowledge beyond what can be known through science alone.

In taking an interpretive epistemological approach, the critical paradigm also highlights the ways that definitions of healthy eating are intertwined with social and structural inequities, such as sexism, classism, racism, as well as hierarchies of knowledge wherein non-dominant (i.e., non-scientific) ways of seeing the world are dismissed as untrue, deceptive, or deluded. For example, the dominant paradigm sees lobster as a universally healthy food because it is low-fat, protein-rich, and high in omega-3 fatty acids. Yet the dominant paradigm obscures the local context in which lobster may be fished, sold, and eaten. For example, in Mi’kmaw’ki/Nova Scotia, where I live and work, lobster has been at the centre of on-going and sometimes violent conflict between commercial lobster fishers—who are predominantly White—and Indigenous Mi’kmaw fishers, whose right to fish is protected by treaties, but which has been repeatedly threatened as a result of settler colonialism and anti-Indigenous racism.

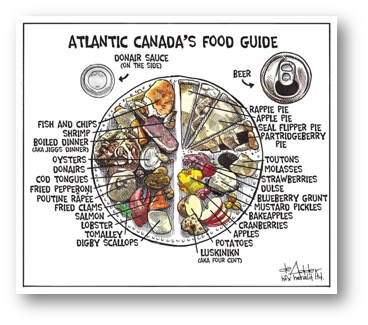

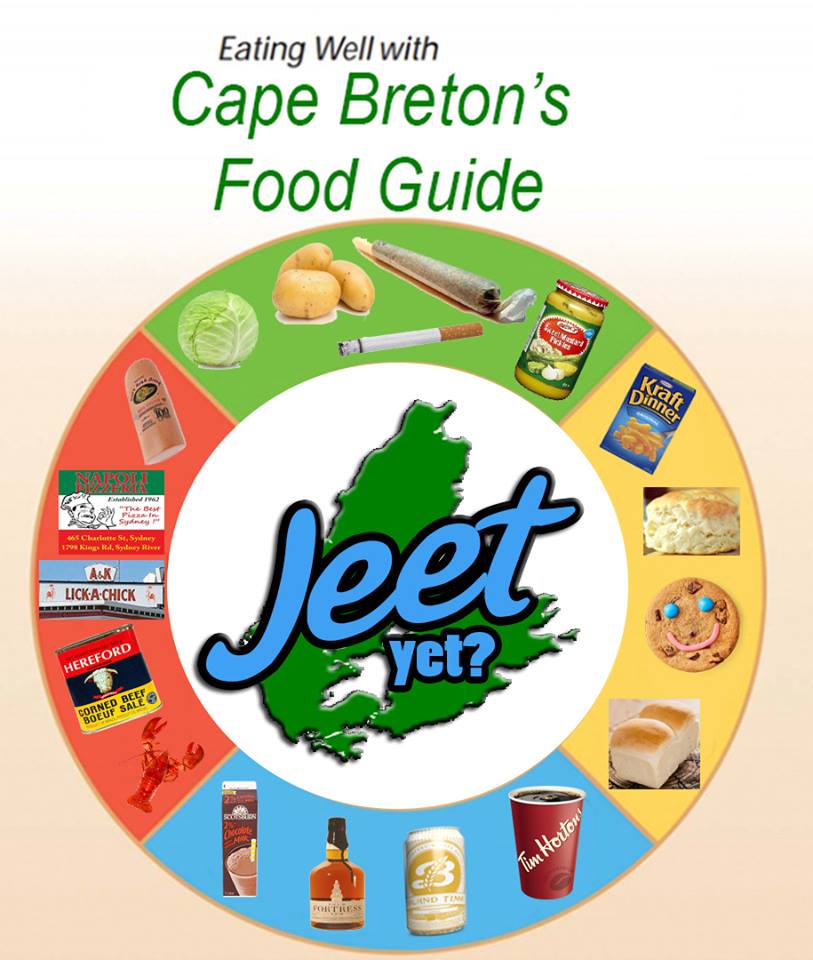

The fundamental differences between the dominant and critical paradigms of healthy eating are well illustrated by Atlantic Canada’s Food Guide (see Figure 2) and Cape Breton’s Food Guide (see Figure 3), both of which were published as satirical responses to the latest version of Canada’s Food Guide shortly after its release.[3],[4] The Atlantic Canada and Cape Breton food guides may be seen as simply poking fun at the gap between the picture of healthy eating depicted by Canada’s Food Guide and the stereotypical eating habits and food culture of those living in Cape Breton and Atlantic Canada. However, they may alternatively be seen as legitimate critiques of Canada’s Food Guide, which does not reflect the social, cultural, economic, and historical realities of those living in Eastern Canada.

One strength of the critical paradigm is its emphasis on the highly contextual nature of food and health, which doesn’t dismiss as unhealthy the foods and ways of understanding health that are meaningful and important to people all over the world. The traditional food and eating habits of Eastern Canadians reflect the region’s rich social and cultural identity that is rooted in its unique history, geography, and climate; some of these are depicted in the Cape Breton and Atlantic Canada food guides. Both guides include a diverse array of foods, such as canned corned beef, lobster, soft rolls, luskinikan, rappie pie, boiled dinner, and donair. Many of these might be unfamiliar or unappealing to those who “come from away” (as those people from the rest of Canada are typically labelled by Eastern Canadians). These foods are also low in fibre and other health-promoting nutrients, and high in calories, fat, sugar, and salt, but are also deeply rooted in the history and culture of the region, and in the identities of those who live here. Are these foods not a part of healthy eating for people living in Eastern Canada?

Another strength of the critical paradigm is its emphasis on the interconnection between social and structural inequities—such as racism, sexism, and poverty—and what people eat and how they understand health. The provinces of Eastern Canada have suffered social and structural inequities as a result of economic hardship and intergenerational poverty. Nova Scotia, for example, and especially Cape Breton island have for decades reported highest rates of food insecurity[5] and poverty[6] compared to all other Canadian provinces. The minimum hourly wage in Nova Scotia falls well below what is considered an adequate living wage, and many people earn salaries that are below or barely above the poverty line[7]. The impact of poverty is even more severe for the Indigenous Mi’kmaq individuals and communities who live throughout the region, and who have fought to maintain traditional food and eating habits despite the impact of racism and colonialism. In short, many of the foods that are visually depicted in Canada’s Food Guide—such as salmon, quinoa, and fresh berries—are both financially out of reach and culturally irrelevant to the people who live in this region.

Canada’s Food Guide, and the dominant paradigm of healthy eating more generally, overlook the contextual factors that shape what is accessible to and considered healthy by Eastern Canadians. What is more, if what we eat is meaningful to who we are (as Brillat-Savarin suggests and as the Cape Breton and Atlantic Canada food guides seem to affirm), then in many ways we are telling people who they should be when we tell them what to eat. The dominant paradigm of healthy eating can thus be seen as overlooking, if not exacerbating, the social and structural inequities that shape what, why, how, and when people eat.

Despite its strengths, the critical paradigm also has shortcomings. Specifically, the critical paradigm provides little concrete guidance about what foods and eating patterns contribute to human health. This insight leads to yet more questions that are important to the ongoing debates about healthy eating that have unfolded within critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics. One such question is: How do we reconcile the strengths of the dominant and critical paradigms? In other words, how can we provide information that may help people eat healthfully, but in ways that do not dismiss or exacerbate inequities, and instead affirm the highly contextual and deeply held meanings of food, eating, and health?

Discussion and implications

The dominant paradigm has led to many health-promoting and life-saving discoveries about healthy eating, including how to manage and treat disease through diet. However, this paradigm has been widely criticized for overlooking the highly contextual nature of healthy eating, which is intertwined with social and structural inequities, as well as the knowledge that is derived from people’s everyday lived experiences of food and eating. Conversely, the critical paradigm has shed light on the highly contextual nature of food and eating, the interconnections between how we define and think about what is healthy to eat, and social and structural inequities. Yet the critical paradigm tends to overlook the scientific evidence, and provides little direction about what and how we should eat to support health. In this light, the question remains: What is healthy eating?

The answer that is currently emerging from critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics points to the need to bring together the strengths and weaknesses of both the dominant paradigm and the critical paradigm. That is, what is needed is an understanding of healthy eating that reflects scientific evidence about the impact of what we eat, but which also incorporates the diverse meanings of food, eating, and health that are rooted in the complex and contextual experiences of people’s everyday lives. How exactly that might unfold is a question on the horizon of the developing field of critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics.

Conclusion

As researchers, activists, practitioners, and students of food and nutrition, our work is often geared toward changing what and how people eat. Questions such as “What is healthy eating?,” and “What does it means to tell others what to eat?” are important and require us to consider the breadth of knowledges that are needed to understand potential responses.

This overview has drawn on key concepts in the field of critical nutrition studies and critical dietetics to explore two epistemological paradigms that provide very divergent responses to these questions. Some of these responses are reflected in the different depictions of healthy eating presented by Canada’s Food Guide and the Cape Breton and Atlantic Canada food guides. Ultimately, what these divergent paradigms indicate is that healthy eating is a terrain of contested meaning that shapes and is shaped by social and structural inequities. In other words, answering the question, “What is healthy eating?” is anything but simple.

Discussion Questions

- Reflexive thinking is important for being aware of our social positionality within systems of power and privilege, such as those that influence how we view healthy eating. Think about what healthy eating means to you and the role it plays in your day-to-day life and in shaping your identity. What informs your conceptualization of healthy eating? How does your conceptualization of healthy eating reflect the dominant and critical paradigms discussed above?

- Recall the Atlantic Canada Food Guide and the Cape Breton Food Guide discussed in this chapter. If you were to create a food guide to reflect the town, region, or country that you call home, what foods or messaging about healthy eating would it include?

Additional Resources

Coveney, J. and S. Booth, eds. 2019. Critical Dietetics and Critical Nutrition Studies. Boston: Springer.

Hayes-Conroy, Allison, and Jessica Hayes-Conroy, eds. 2016. Doing Nutrition Differently: Critical Approaches to Diet and Dietary Intervention. New York: Routledge.

Koç, Mustafa, Jennifer Sumner, and Anthony Winson, eds. 2021. Critical Perspectives in Food Studies, 3rd edition. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parker, Barbara, Jennifer Brady, Elaine Power, and Susan Belyea, eds. 2019. Feminist Food Studies: Intersectional Perspectives. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rebel Eaters Club, S2 E5: “Eating 101 with Dr. Jennifer Brady.”

References

CMikeHunt. “Substitute donair for Lick-a-chick and you’ve got a Halifax version.” Reddit, January 25, 2019.

Brillat-Savarin, J.-A. 2007. Physiologie du goût. Project Gutenberg.

deAdder, M. “Atlantic Canada’s Food Guide,” Chronicle Herald, January 28 2019.

Driscoll, C. and C. Saulnier. “Living Wages in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick 2020” (website). Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Accessed May 1, 2021.

Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide (website). Accessed May 1, 2021.

Saulnier, C. and C. Plante. “The Cost of Poverty in the Atlantic Provinces” (website). Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Accessed May 1, 2021.

Tarasuk, V. and A. Mitchell. “Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18” (website). PROOF. Accessed May 1 2021.

referring to academic approaches that focus on observing, analyzing, and acting upon systemic structures such as bias, inequity, or difference.

an interdisciplinary field that draws on the perspectives and tools of critical social theory to illuminate the ways in which nutrition and healthy eating are shaped by and shape social and structural inequities in society.

an interdisciplinary field that draws on critical social theory to explore power in relation to food, nutrition, and healthy eating; includes the knowledge base, education and training approaches, and regulatory frameworks within the dietetic profession.

the unfair and systematic outcomes experienced by different groups in society that are reinforced by the structural organization of that society.

a framework, or way of thinking, commonly accepted by members of a given knowledge community; a model of something that serves as a reference point, or standard, for other iterations of that thing.

the systems by which one country or socio-political group rules, governs, or dominates another.

an approach to knowledge that takes empirical evidence—data derived through observation of phenomenon—as the means to uncovering objective truths about the world.

the practice of viewing knowledge as created through and inseparable from the observations and context of the observer; interpretive epistemology is always subjective.