Perspective: Food Access

Laine Young

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Differentiate among the concepts of food deserts, food swamps, food mirages, and food oases.

- Articulate the differences between food environments in specific urban areas.

- Identify the barriers to food access—like transportation, income, and time—and the socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in food access.

Introduction

There are many factors that influence people’s access to food in a town or city. Some are specific individual barriers (e.g., income), but often there are larger structural issues (e.g., racism, discrimination, resource inequity). These barriers can be social, economic, or physical. To evaluate food access, it is important to be able to differentiate among the food environments that people belong to. Neighbourhoods struggling with food access within cities can be food deserts, food swamps, or food mirages. Those with superior access to food are considered food oases. The number and quality of healthful and affordable options for access to food in each neighbourhood determines which food environment the area belongs to. We differentiate between these environments because each problem is unique and requires specific solutions to improve food access. This chapter explores the different food environments in communities and how they affect access to food. It provides examples of work that has been done to mitigate these barriers to access in the city of Toronto, Ontario.

Food Environments

While health promotion materials tend to emphasize the importance of individual food choices, access to healthy food is primarily determined by the social and built environments, including “community” and “consumer” nutrition environments. The community nutrition environment is determined by “the number, type, location and accessibility of food outlets such as grocery stores,” and the consumer nutrition environment is categorized by what “consumers encounter in and around places where they buy food, such as the availability, cost, and quality of healthful food choices.”[1]1 Food environments are affected by both community and consumer nutrition environments.

The conditions of different food environments within neighbourhoods can have an impact on access to food for the residents that live there. Negative food environments are those in which healthy food access is limited or difficult due to lack of retail options, cost, transportation and mobility, and availability of culturally appropriate foods. They have been linked to communities whose demographics indicate they have a lower socio-economic status, as well as racial and ethnic disparities. These inequities in the food environment can be partially attributed to racial segregation in neighbourhoods. For example, certain neighbourhoods in the U.S. where residents are predominantly Hispanic and Black have less access to large, chain grocery stores, and more access to fast food.[2]2 This is not always the case, as we sometimes see higher-income neighbourhoods without grocery stores and other nutritious food sources. The difference is that people living in higher-income communities typically have the money to purchase more expensive options close by, have vehicles to drive to buy food, and typically don’t have the same time constraints or accessibility issues as those in lower-income neighbourhoods.

There are currently four examples of food environments that appear in the literature: food deserts, food swamps, food mirages, and food oases. It is important to distinguish between these environments, given that different strategies are needed to mitigate the different risks in each3.[3] Food deserts are areas of a city where residents lack physical and/or financial access to nutritious food. People living in rural areas may also need to travel long distances to get their food and are often left out of the food environment literature.[4]4 In Canada, people are more likely to experience food swamps, areas that have nutritious food stores but also have an abundance of unhealthy options that are more accessible.[5]5

Another food environment that is important to discuss is food mirages. In this case, healthful food options are available, but not affordable to those with low incomes, requiring them to travel long distances for access to affordable food.[6]6 Food mirages differ from food deserts because it appears that the neighbourhood has healthful food options close by, but they are not actually usable resources for some members of the community (because they cannot afford to shop there). In addition to affordability, there are also other potential access issues for the residents of the neighbourhood. Food access is more than financial, as a household’s physical ability to get to and navigate the stores (e.g., because of disability or age) can restrict their access. Many also experience time poverty,[7]7 for example, if they work several jobs, use public transit, or are the primary caregiver in their household; in these cases, the number of hours left in their day to acquire food is much less than in other households. Finally, a food oasis is a neighbourhood with superior access to nutritious foods.[8]8

Table 1: Negative food environments and their characteristics (Young 2021)

| Food Deserts | Food Swamps | Food Mirages |

|---|---|---|

| Residents lack physical access to nutritious food. They are unable to walk to find nutritious food. They must have access to transportation. | Residents have access to nutritious food, but unhealthful options are more abundant. | Residents have nutritious food options close by but they are unable to afford it. |

| There are few options in the community to purchase nutritious food (i.e., grocery store, healthful restaurants). | Community has nutritious food options, but the unhealthful options are more accessible (i.e., fast food, convenience stores). | Community has nutritious food options, but the unhealthful options are more affordable (i.e., fast food, convenience stores). |

Measuring Food Access

In order to determine how to classify a neighborhood’s food environment, community food assets need to be measured. A food asset is a place where local residents can go to “grow, prepare, share, buy, receive or learn about food”[9]9 through, for example, community programs, retail outlets, urban gardens, and fresh food markets. Determining the number of food assets in a community can be challenging without a tangible way to collect the data. Toronto Public Health’s Food Strategy and the Toronto Food Policy Council created a way to measure the available food assets in the city, providing a tool to advocate for food environment change.

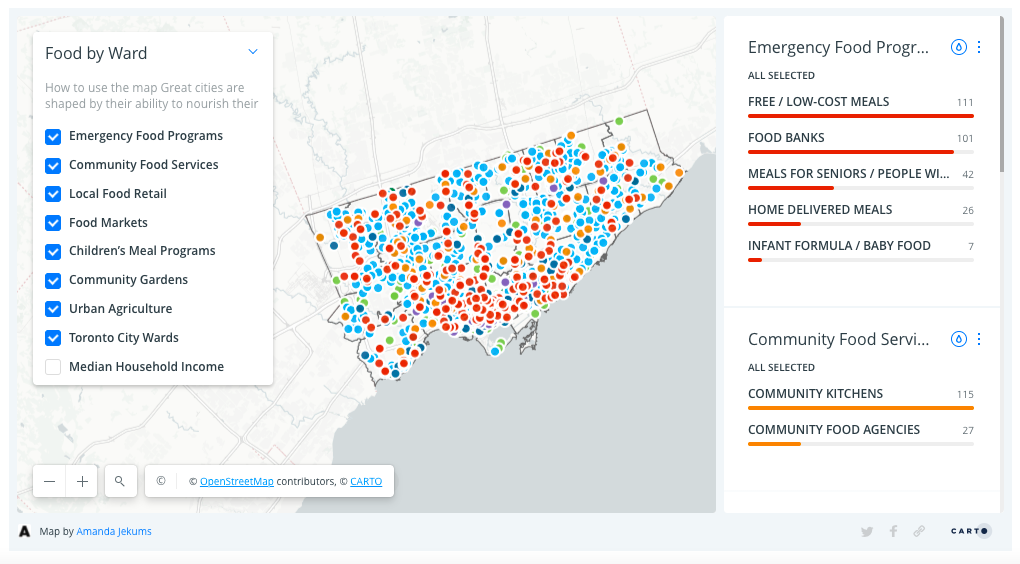

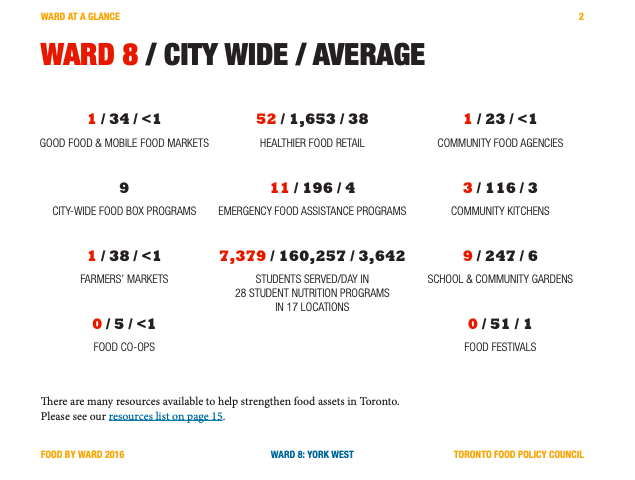

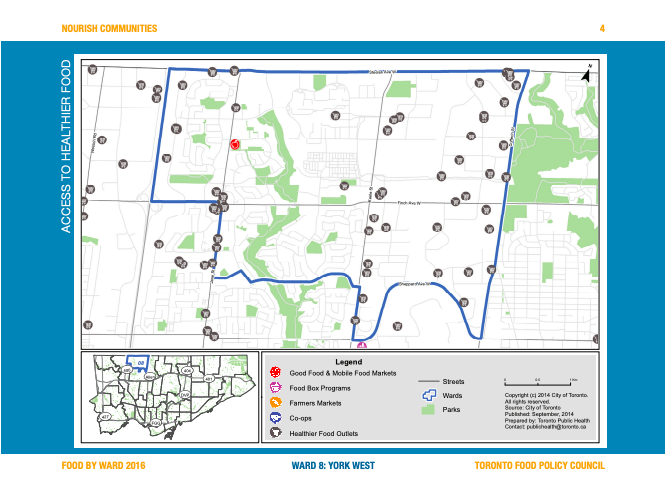

Toronto's Food by Ward project was created as a way of measuring the unequal distribution of food assets across the city’s neighbourhoods.[10]10 This information was collected through grassroots organizing in each city ward. In each area, Food Champions led the data collection through several rounds of community consultations. Food Champions are “people who care about food, healthy communities, and economic development, and (who) are working together to protect, promote, and strengthen food assets.”[11]11

The food asset categories that were collected within the Food by Ward project included: emergency food programs, community food services, local food retail outlets, food markets, children's meal programs, community gardens, and urban agriculture projects.[12]12 The data was collected and mapped, so residents and policy makers could visualize the assets, as well as determine which communities were lacking or had an abundance of food. This provided community organizers with the data needed to approach City Council representatives in their specific wards and advocate for change. This project makes the case that food-related projects and development are just as important as other urban infrastructure.[13]13

Food by Ward is an excellent example of measuring food access, but is highly dependent on resources to maintain the data. Without dedicated funding, the tool is not sustainable. While the tool itself is not currently being maintained across all of metropolitan Toronto, some individual neighbourhoods, like Rexdale, have taken on their own asset mapping on a smaller scale. This allows each neighbourhood to ensure that their maps are updated and reflect their current situation. Food asset mapping has a lot of potential for measuring access to food, but there needs to be a sustainable approach, including the human and technical resources needed to maintain the data.

Toronto’s Response to Negative Food Environments

Cities have the potential to mitigate the impact of challenging food environments through initiating policy and programs that increase nutritious food access in the areas that need it most. The city of Toronto has many geographic areas that fall under the above-mentioned negative food environments. Toronto Public Health’s Food Strategy has implemented many initiatives to combat this in the city. The Food Strategy uses a “food-systems perspective” that focuses on nutrition, prevention of diseases, food literacy, social justice, food supply chains, economic development, environmental protection, and climate change mitigation.[14]14

Grab Some Good

In 2014, one of the key projects of the Toronto’s Food Strategy was called Grab Some Good. This project was initiated to combat the lack of equitable access to healthy food across the city.[15]15 Many Canadian cities, Toronto included, technically do not have food deserts and, for various reasons are far likelier to have food swamps.[16]16 Grab Some Good was a partnership between the Food Strategy and community partners like FoodShare.[17]17 (FoodShare is a food justice organization in Toronto that provides nutritious food to people across the city. They collaborate with the people most affected by poverty to create long-term solutions to food problems.) The three major projects that evolved were Healthy Corner Stores, Mobile Good Food markets, and Subway Pop-Up markets. The goals of Grab Some Good were:

- To offer healthy, affordable and culturally diverse fresh food to residents living in areas that are underserved by healthy food retailers.

- To provide fresh produce at convenient locations at prices that are lower than the average grocery store.

- To promote healthy and sustainable eating habits among all Toronto residents and to support good nutrition and disease prevention interventions.[18]18

The Healthy Corner Store initiative provided logistical and infrastructure support to local corner stores, aimed at increasing the healthy food available to people in the surrounding neighbourhoods and at ensuring that the owners were making profit from the endeavor.[19]19 To address the issue of minimal grocery store availability in underserved neighbourhoods, the Food Strategy and FoodShare launched mobile food markets in 2012. These retrofitted wheelchair buses were transformed into mobile food markets and served affordable, healthy food to 11 low-income neighbourhoods in Toronto.[20]20 The Toronto Transit Commission pop-up markets, another partnership with FoodShare, were established in major transit hubs and provided commuters with access to healthy snacks, as well as fruits and vegetables to take home with them without needing to stop at a grocery store.[21]21

Each of these three projects attempted to mitigate the negative effects of neighbourhoods found in food swamps in innovative and community-focused ways. They were successful in improving access to nutritious food in the neighbourhoods they served. They offered innovative solutions to food environment problems. Unfortunately, the overarching issue with these types of projects is the lack of financial sustainability. As they all required some degree of municipal funding, the longevity of the projects was not guaranteed and they are therefore no longer running. Nonetheless, these cases show that if municipal governments can prioritize funding to address food swamps, deserts, and mirages, or if community organizations can build self-sustainability, there is great potential to make changes to the way food is accessed in these communities.

Good Food Markets

One of FoodShare’s many successful projects is the Good Food Markets. These markets are found across the city in neighbourhoods that lack access to nutritious food and are run by the community members themselves. The program trains community members on the necessary skills and information needed to run the markets and provides the tools and resources necessary for sustainability.[22]22 The Good Food Markets not only provide access to food, they work more holistically—as community hubs that engage and connect residents in their own neighbourhood.[23]23 This type of community engagement is important for neighbourhoods to build social cohesion and strengthen the residents’ ties to their community. This model has great potential for success because it is sustainable and driven by the needs of those who use it.

Conclusion

To ensure healthy communities, it is important to measure food access within specific neighbourhoods. Identifying the type of food environments that communities reside within can help inform targeted responses by municipal governments and community organizations.

It is critical to address the racial and ethnic disparities present in negative food environments. This necessitates structural change through policy-making, planning, and development, in order to address diet quality (related to food environments) within white and minority populations.[24]24 Such efforts should address the disparities in access to healthful food in neighbourhoods to limit the impact on nutrition and health outcomes.[25]25

Toronto Public Health’s Food Strategy and FoodShare have shown great examples of engaging in innovative solutions to manage food access, but there are funding challenges that can have an impact on the capacity to help communities in the long-term. Moving towards the community hub model has great potential to improve food access and serve communities in a holistic way.

Discussion Questions

- How might systemic discrimination, based on the demographics and experiences of residents within a neighbourhood, influence their food environment?

- Do you notice any differences in perceived access to food between low- or high-income neighbourhoods in your community?

- What kinds of impacts related to food access might residents of diverse racial or ethnic backgrounds experience in their communities?

Exercise

Additional Resources

FoodShare website

Food by Ward Website

Yang, Meng, Haoluan Wang, and Feng Qiu. “Neighbourhood Food Environments Revisited: When Food Deserts Meet Food Swamps.” The Canadian Geographer 64, no. 1 (2020): 135–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12570.

CBC article, “Chinatown BIA slams study calling area 'food desert'.”

Canadian Public Health Association “Mobile good food market brings healthy choices to neighbourhoods in ‘food deserts’.”

References

“Advancing Food Access.” FoodShare. Accessed June 9, 2021.

“Food by Ward.” Toronto Food Policy Council. Accessed June 9, 2021.

“Food Deserts.” Canadian Environmental Health Atlas. Accessed June 9, 2021.

Chen, T. and E. Gregg. 2017. “Food Deserts and Food Swamps: A Primer.” National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health.

Glanz, K., J.F. Sallis, B.E. Saelens, and L.D. Frank. 2007. “Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S).” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 32 (4): 282–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.019.

Stowers, K.C., Q. Jiang, A.T. Atoloye, S. Lucan, and K. Gans. 2020. "Racial Differences in Perceived Food Swamp and Food Desert Exposure and Disparities in Self-Reported Dietary Habits." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (19): 1gx+.

“Toronto Food Strategy: 2016 update.” Toronto Public Health.

“Vancouver Food Asset Map.” Vancouver Neighbourhood Food Networks. Accessed June 9, 2021.

Yang, M., H. Wang, and F. Qiu. 2020. “Neighbourhood Food Environments Revisited: When Food Deserts Meet Food Swamps.” The Canadian Geographer 64 (1): 135–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12570.

- Glanz et al. 2007, 282. ↵

- Stowers et al. 2020. ↵

- Yang et al, 2020. ↵

- Chen & Greg, 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Yang et al. 2020. ↵

- Canadian Environmental Health Atlas, n.d. ↵

- Yang et al. 2020. ↵

- Vancouver Neighbourhood Food Networks. ↵

- TFPC, n.d. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- TPH, 2016. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 16. ↵

- TPH 2016. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- FoodShare n.d. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Stowers et al, 2020. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

one way in which a city is divided into units of governance or management; e.g., city councillors may be elected by wards.