8.9 Move

Check Yourself

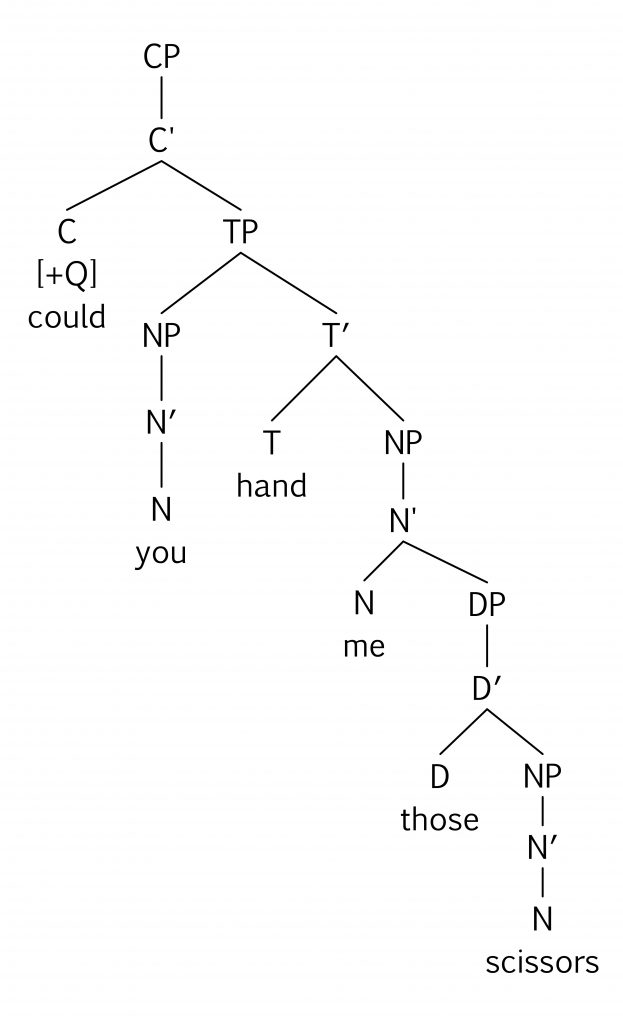

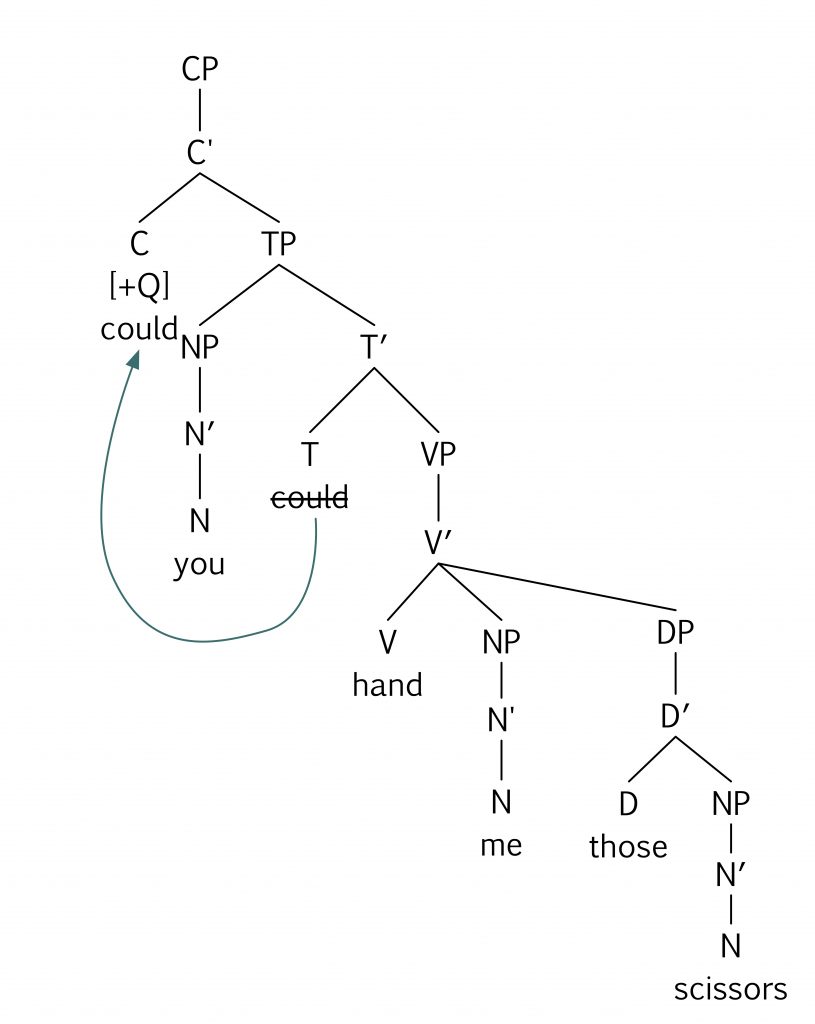

1. Which tree diagram correctly represents the question, “Could you hand me those scissors?”

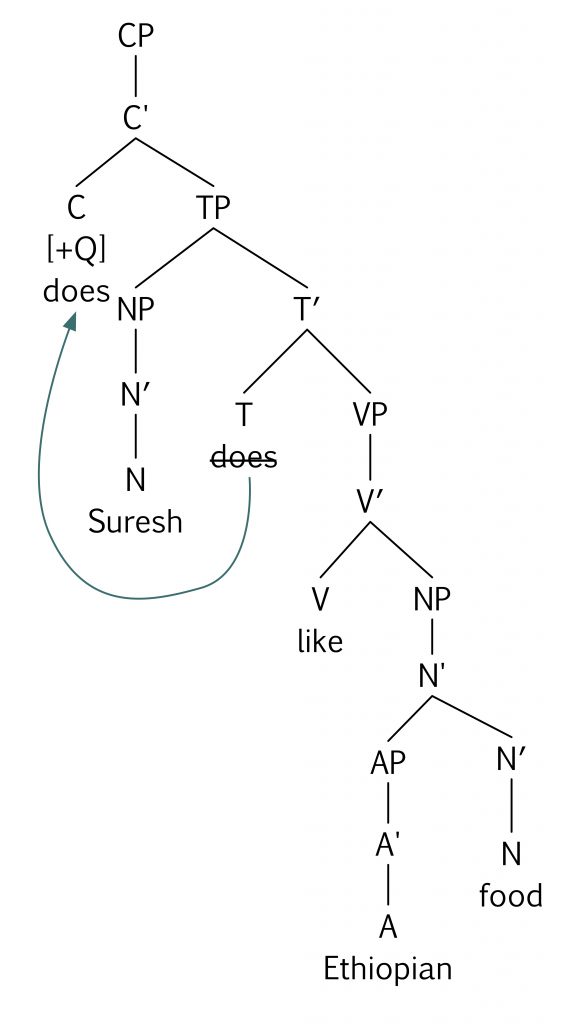

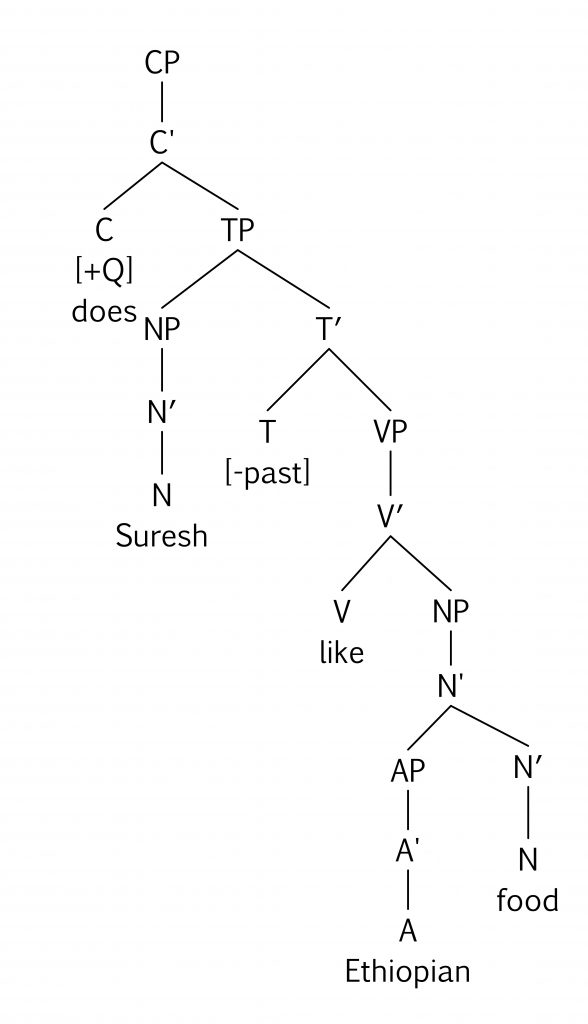

2. Which tree diagram correctly represents the question, “Does Suresh like Ethiopian food?”

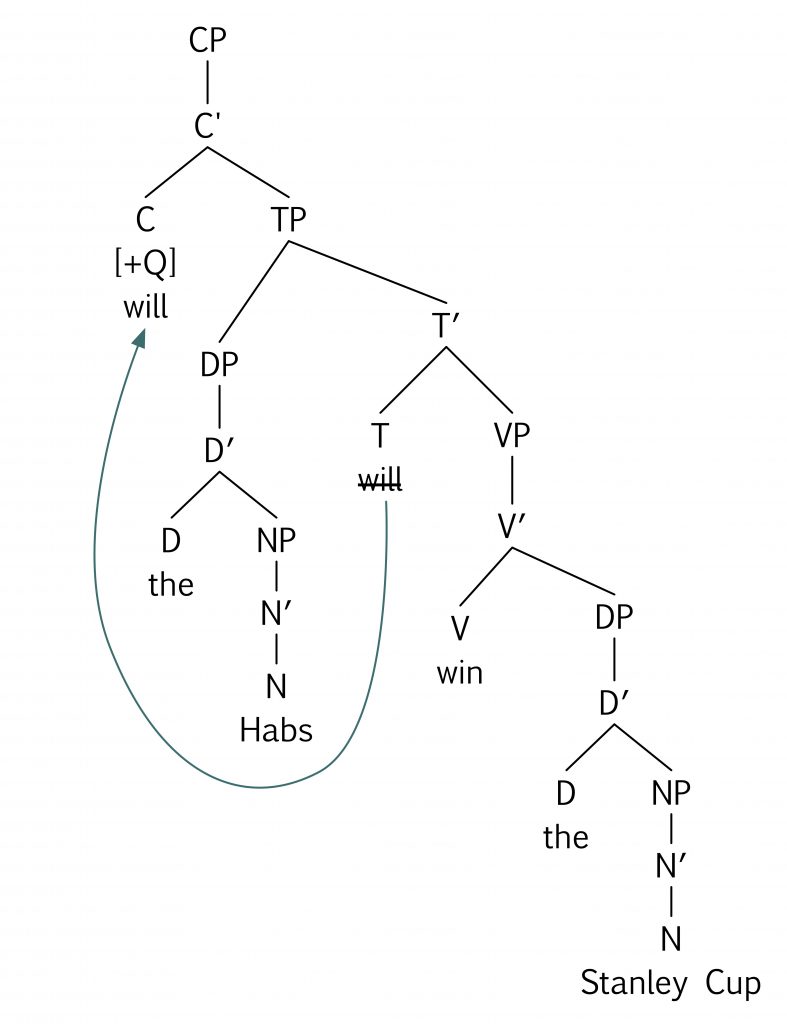

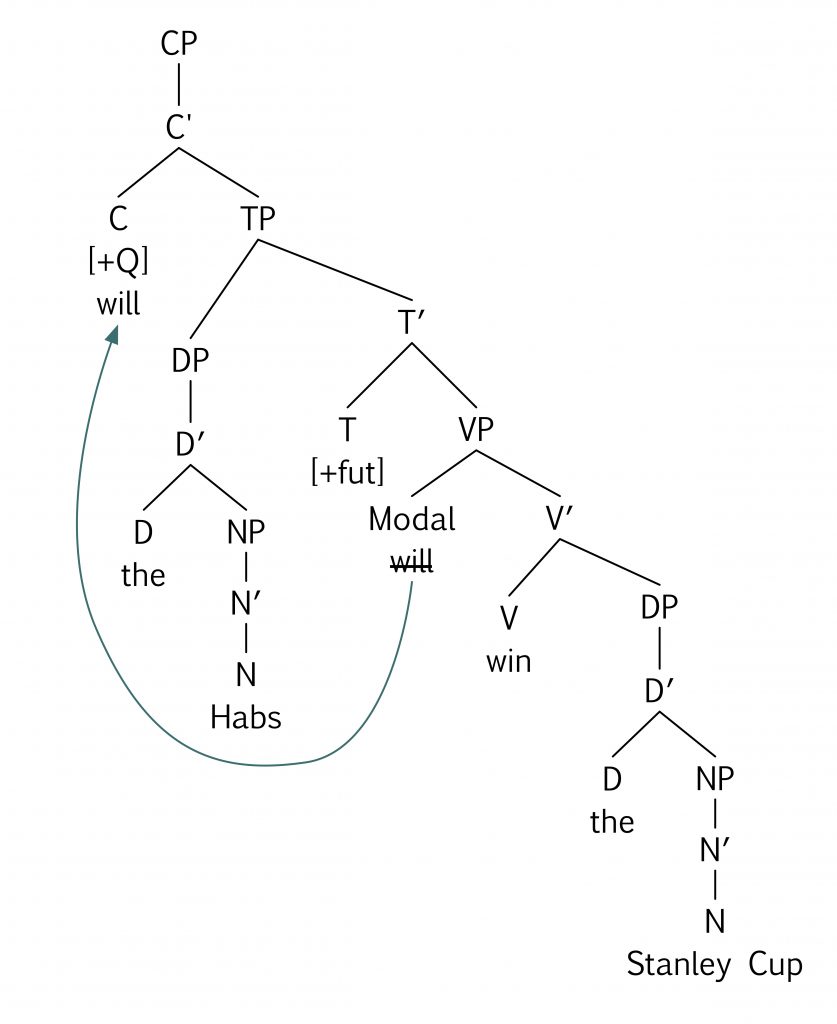

3. Which tree diagram correctly represents the question, “Will the Habs win the Stanley Cup?”

Video Script

We’ve developed a model of the mental grammar that says that we draw words, morphemes, and morphosyntactic features from our mental lexicon, and then the operation MERGE combines all these items into a grammatical x-bar structure. In this unit, we’re going to look at another operation of the mental grammar, called MOVE, which takes a part of a sentence and moves it somewhere else in the sentence. But why would we want to do that? Let’s look at some examples to figure it out.

Let’s take our now-familiar sentence, Ann hopes that the Leafs will win. Hope is one of those verbs that takes a whole clause as its complement, and that clause is introduced by the complementizer that in C-head position. But what if Ann isn’t hoping, what if she’s asking whether there’s any possibility of her hopes being realized? If she’s asking instead of hoping, the complementizer that doesn’t work as well here. It’s grammatical if we use the complementizer if. I’m going to suggest that the reason the complementizer that doesn’t fit very well in this position is because the verb head ask doesn’t just subcategorize for a complement clause — it’s even pickier than that! The verb ask subcategorizes for a question clause. And the difference between a regular complement clause and a question clause is that a question clause has a [+Q] feature in the C-head position.

So we’re seeing another instance of a morphosyntactic feature occupying a head position. The strange thing about features is that they don’t get pronounced. We know that morphemes and words link up a form (either spoken or written) with a meaning. But features have meaning and don’t have any form of their own. The tense feature does its job by making sure that its complement has the right form. And one way that the [+Q] feature does its job is by making sure that the thing in the C-head has the right form. So if is ok when the C-head has a [+Q] feature in it, but that is not so good.

There’s another way that the [+Q] feature can make itself noticed, though. In English, if we want to ask a question, we don’t do it like this: If the Leafs will win? How do we form that question when it’s not embedded inside another clause? Of course, it’s Will the Leafs win? How did that modal will get from its position between the subject and the main verb up to the beginning of the sentence? Here’s where the operation MOVE comes in.

The theory claims that the operation MERGE generates this structure for the question. This looks just like the declarative sentence, The Leafs will win, except that it has a [+Q] feature in the C-head position. That [+Q] feature needs people to know that it’s there; it’s not like the null complementizer that doesn’t mind being silent: it changes the meaning of the sentence so it wants to be pronounced. For questions that are main clauses themselves, it’s not grammatical in English to just stick a question complementizer into the C-head position. So instead, the operation MOVE comes along, picks up the modal from the T-head position, and moves it up to the C-head position.

But when the modal moves from T up to C, the T position doesn’t disappear from the tree. Instead, the thing that moved leaves behind a little footprint or shadow of where it used to be. In the theoretical literature, it’s called a “deleted copy” or a “trace” — the idea is that it’s still there in the T-head position in our mind, even though we pronounce it up in the C-head position.

Notice that now we’ve got two levels of representation in our syntax. MERGE generates the underlying form of a sentence, what we’ll call the Deep Structure. And then MOVE comes along and, well, moves things, to give us the Surface Structure. A lot of the sentences that we’ve been looking at so far have the same deep structure and surface structure, but when we look at questions, we can see that a sentence can have some systematic differences in how it’s represented at the two levels.

One thing I want to point out is that when we observe sentences, and when we make grammaticality judgments to observe whether a sentence is grammatical or not, what we’re observing is always the surface structure. The Surface Structure is the form of the sentence that we speak: it’s the form that’s out there in the world. We can’t ever observe the Deep Structure; that’s the form of the sentence that exists in our minds. But some of the things that we observe about Surface Structures allow us to conclude that the Deep Structure does exist in our mind and that it’s related in a systematic and predictable way to the Surface Structure. We can represent the relationship between Deep and Surface Structure using a tree diagram.

Just to make this idea about levels of representation clearer, let’s look again at these sentences. The idea is that when these two sentences, one a question and one a declarative sentence, are generated by MERGE, they have almost the exam same Deep Structure. The only difference between their Deep Structures is that the question sentence has a [+Q] feature in C and the declarative doesn’t. The declarative sentence is pretty much ok, so it doesn’t need the MOVE operation to do anything, so its Surface Structure is the same as its Deep Structure. But the question sentence needs to get its [+Q] feature expressed, so MOVE comes along and forms a Surface Structure that’s different from its Deep Structure. So the two sentences that were almost the same in their Deep Structures have one crucial difference between them in their Surface Structures.

We saw that when a sentence has a modal in the T-head position, that modal can move up to the C-head position to support a [+Q] feature. What happens when we want to form a question from a sentence that doesn’t have a modal in the T-head position? What about a sentence like this one? Samira phoned.

We know that the T-head node has a tense feature in it. In a declarative sentence, that tense feature makes sure that the V-head in its complement has the right feature — in this case, the past tense form phoned. But we certainly don’t form a question from this sentence by asking, “Phoned Samira?” What happens in this kind of sentence is that we bring the auxiliary do into the T-head position. Because in this case the tense feature is [+past], do becomes its past-tense form did. Now that the past tense feature is on the auxiliary, it won’t be on the lexical verb, so the verb phoned in V-head just takes its bare form phone. And then to get the [+Q] feature supported, MOVE takes did from the T-head position and moves it up to the C-head position, leading to the Surface Structure, “Did Samira phone?”

Your challenge now is to think about how our mental grammar forms yes-no questions for sentences that have non-modal auxiliaries in them. What do the Deep Structure and Surface Structure look like for each one? Try to figure it out!