Module 2: Program Vision, Feasibility, and Planning

Creating and Aligning Program Vision

Greg Yantz

A vision is “a thought, concept, or object formed by the imagination” (Merriam–Webster, n.d.). When thinking about a vision for an online program, what do you imagine the new online program will be, and what does it include? What metrics will you use to measure success?

The program vision reflects the high-level goal(s) and purpose that form the foundation of any program framework; it is central to understanding the program, its needs, and if the goals you’ve set for the program have been met and can be sustained. If we think of program design as a journey, the vision is the destination, and the trip to get there is the program development and implementation process. The teams that do this work need to understand and articulate the program vision so they can set program outcomes and goals, then measure and assess whether they have been met. In other words, the vision enables you to determine the destination and how you will know when you’ve arrived.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Articulate a vision for the program that aligns with the discipline/s and reflects the needs of various stakeholders

- Articulate a vision that aligns with relevant institutional, provincial, and national strategies

- List the required and available resources for program development

You will take away:

- A process you can follow to develop a program vision statement that is aligned with institutional strategies

- A draft resource plan that identifies key partners and the consultations needed to assess the costs of your online program

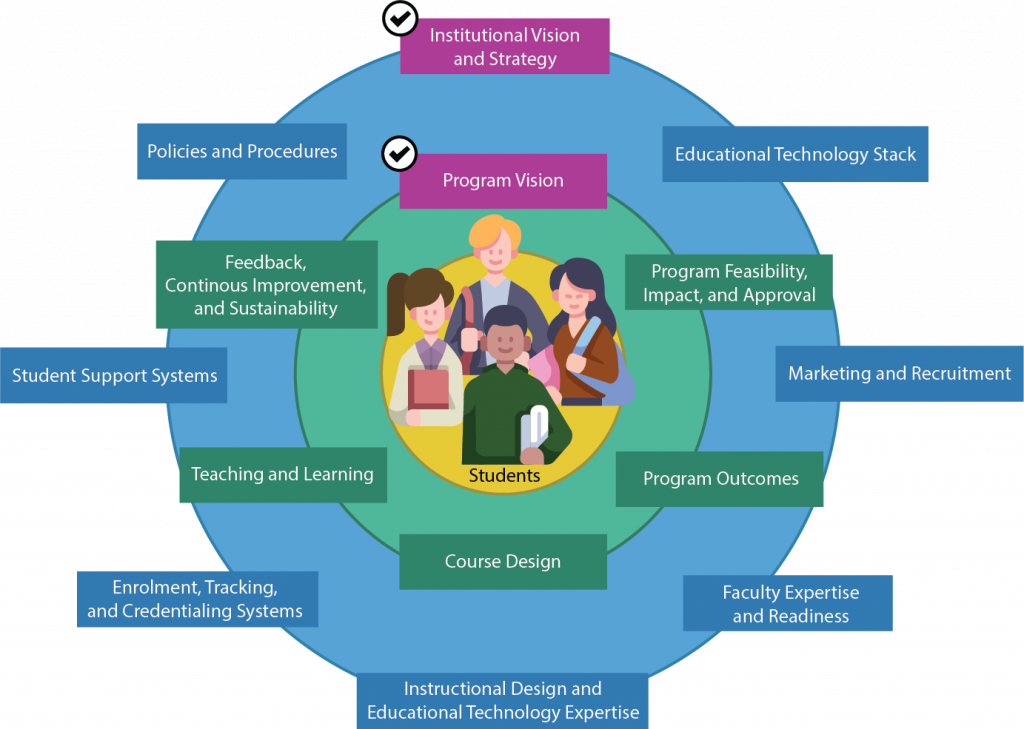

This unit focuses on the Institutional Vision and Program Vision elements of the Online Program Ecosystem. Read more about the ecosystem in Module 1, Unit 1: Collaborating to Create the Online Learner Life Cycle and its Ecosystem

Why Have a Program Vision?

Simon Sinek (2011) notes in Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action that a starting point for any vision is determining an answer to the very basic “why” question. In the case of a new program, the answer to “why” addresses the core purpose or the reason for the program. Creating the vision requires collaboration by a team, both within an institution and potentially with those external to the institution who have subject matter expertise and knowledge about the discipline and its purpose. Creating a vision provides the foundation for the program, and the vision should be reviewed regularly to ensure the desired purpose and values for the program remain in focus.

Watch the first three minutes of Simon Sinek’s video (TEDX Talks, 2009) about understanding your “why”.

Workbook Activity: After viewing the video, can you clearly articulate the “why” for your online program? More importantly, is it evident to others? If you have a vision statement, add it to the Program Design and Implementation Workbook for future reference. Use the “What is Your Why” reflection activity that follows it help ensure that your vision is clear, relevant, and reflects the needs of all internal and external stakeholders. In some cases, you may find you need to engage in consultation and collaboration to answer those questions. We suggest processes for this in the “Creating an Online Program Vision” section below.

Do you know your “why”?

Your vision is the “why” behind your online program, and creating your vision focuses on reflection and discussion with others about the answer to “why?” as well as the foundational principles for the program.

As referenced throughout this book, collaboration is the action of working with others to produce or create something together that improves upon what could be done alone. In the case of creating a vision for an online program, collaboration means taking an evidence-informed, team approach to understanding the “why” behind the need for the program. At the high-level visioning stage, collaborators work together to address the following questions:

- Why is this program important?

- What are the unique advantages of the program—what makes it distinctive?

- How does the program contribute to the needs of the university or college community and the broader local, provincial, and global community?

- How do we define success in this program, and how will we know that the program has been successful (what metrics will you use)?

The above questions are useful when visioning any new program. There are also some additional questions specific to online programs that should be considered during your visioning process:

- Why online? What is your rationale for developing an online program specifically?

- How will offering the program online build institutional capacity by allowing connections with new types of students, whether in new geographical areas or those who were previously underserved?

- Does an online offering provide better access and flexibility for students?

- Is institutional strength enhanced through offering a program in an online delivery format?

Before we share more about how you might go about answering these questions and creating a program vision, let’s hear from a leader who has experienced firsthand how important it is to create an evidence-based program vision that speaks to your strengths.

Now that we’ve thought more about the importance of the online program vision, we can see how some of the “Do You Know Your Why?” questions are embedded in two real-world online program examples.

Examples of Program Vision Statements

➊ The Social Media Communications Program

The Social Media Communications Program develops intermediate-level critical thinking and writing skills together with technical knowledge of social media platforms. The goal of the program is to develop individuals who can understand and use social media in an ethical and meaningful way. The program provides graduates with the necessary background to enter the workforce as social media coordinators or social media strategists.

➋ The Higher Education Program

The Higher Education Program inspires and supports high-quality practice in community colleges, universities, and college transition programs throughout the region and nation. Its curriculum reflects leading-edge thinking in design as well as implementation, and its graduates routinely:

-

- assume leadership positions in teaching and administration in community colleges and universities throughout North Carolina and beyond;

- are relied upon as catalysts for meeting the evolving social, economic, political, and global challenges facing higher education; and

- are recognized for their strong academic preparation and achievements as they continue their education.

In addition, the Higher Education Program faculty is utilized as a vital professional development resource for community colleges and universities in the areas of instructional improvement, institutional leadership and change, college- and career-readiness, and college access and success for non-traditional and adult students. Faculty, students, and graduates, together with their partners in the field, promote effective and compassionate higher education practice at the individual, program, and institutional level and proactively negotiate the shifting demands of an increasingly diverse and complex world. (Appalachian State University, n.d.)

Creating an Online Program Vision

As you might have guessed from the “Do You Know Your Why?” questions and video, creating an online program vision involves gathering information from multiple stakeholders and data sources. While the process you use for this may be guided by your institutional policies and procedures, there are some common stakeholders and steps that will contribute to your visioning success.

Identify Program Stakeholders

Identify individuals to be included in the discussion and creation of the vision. Individuals or groups involved in visioning should be able to respond to the “why” for the potential program idea and articulate how a successful program will create impact. Examples of individuals or groups to include:

- Current faculty who are experts on the topic or discipline

- Experts in online delivery, such as educational developers or online curriculum specialists, instructional designers, and learning management system specialists

- Community partners who may also be subject matter experts, want to hire graduates and know what is required to be successful

- Current students and potentially those who may be interested in taking the program

- Alumni who may have an interest or expertise in the subject area

- Administrators and staff who will need to support the program such as librarians, academic advisors, marketers, recruiters, and those from international focused areas of the institution

- Individuals who can provide expertise specific to equity, diversity, and inclusion and First Nations, Inuit, and Metis knowledge

Create a Plan Where Stakeholders Can Exchange Ideas and Information

Most commonly, you might organize a series of meetings or a retreat with the visioning team. Retreats work best as a way to focus the discussion and make the most efficient use of everyone’s time. Not everyone can always make in-person meetings, however, so consider how you might also collect data using surveys or shared documents such as a Google Doc or Office 365. One facilitation model for holding a visioning retreat is a Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results (SOAR) retreat, described in more detail below. An example facilitation plan is also included at the end of this unit.

We suggest a smaller, core group be responsible for drafting the vision after an initial visioning retreat or series of meetings. They can then circulate the draft to the larger group for feedback and make any final revisions. And remember, you are visioning for an online program, so part of your discussion should be related to the “why” of developing the program for an online audience.

Creating an Online Program Vision in Five Steps

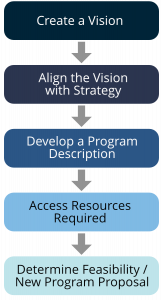

The process for creating a vision will commonly follow four steps:

- Complete a creative/drafting process (e.g., SOAR retreat)

- Create a draft program vision

- Collect reflection and feedback comments from stakeholders on the draft vision

- Revision of the vision statement (and sometimes back to step 2, as necessary)

- Finalize the vision statement & share it with the community (note: steps 3-5 may be repeated depending on feedback at this point)

Example Visioning Retreat Process: SOAR

What is SOAR?

“SOAR (an acronym for Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results) is a framework to guide strategic conversations related to leveraging and building on academic program strengths. A SOAR retreat allows those envisioning an online program to take a strengths-based and data-driven approach to curricular visioning and planning. Retreat participants can include a range of program stakeholders (instructors, administrative staff, students, employers) to ensure that program visioning incorporates a broad set of perspectives.” – (Anstey & Haque, n.d.)

The following SOAR resources can be used and modified as necessary to plan and facilitate a program visioning retreat:

- Creative/drafting process Sample Retreat (Anstey & Haque, n.d.)

- SOAR Facilitator Notes (Hundey, et al., 2019)

- SOAR Retreat Participant Agenda (Hundey, et al., 2019)

Aligning Your Vision

Once you have developed your Program Vision, aligning it with other institutional strategies will support the rationale for its development. Decision-makers want to know why they should provide resources for a new online program and how it will contribute to, or benefit from, institutional and provincial strategies. Alignment with external requirements, such as accreditation standards or strategic goals, is also often required for Ministry approval and funding, particularly for colleges. In these instances, it is important to align the strategic goals and any external requirements with the vision for the program so that its connections can be clearly seen by everyone. Beyond simply the “why,” it requires thought with respect to other factors such as cost and resources. As we discuss later, there is a connection between alignment with strategic goals and the feasibility of an online program.

Workbook Activity: After reflecting on the strategic goals and external requirements relevant to your online program, write down your top 3-5 priorities in the workbook that align your program vision to larger strategies.

For example:

- The program vision must align to the new institutional eLearning or Online Learning Strategy for funding purposes.

- The program vision must align with the new Strategic Mandate Agreement (SMA).

- The program vision must align with several key areas of the institution’s strategic plan.

If you used the SOAR retreat to articulate your vision, you have already identified key areas to consider for alignment and have noted them in the workbook. If not, then an example and template for aligning the vision to strategies and requirements are provided below. Collaboration with those previously identified to support vision creation will provide the best outcome, and collaboration is important for the inclusion of different perspectives as well as creating buy-in for the program. Remember: this alignment is used to articulate the need for an online program and as a metric for program success. The exercise is best completed at a meeting of the group where the final program vision is provided in advance along with a request to reflect before the meeting discussion.

The following links provide examples of external strategies or requirements to which you might align your program if relevant:

- eCampusOntario

- Ministry of Colleges and Universities

- Council of Ontario Universities

- Ontario College Quality Assurance Service

- Postsecondary Education Quality Assessment Board

- Colleges Ontario

- Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario

- Ontario Universities Council on Quality Assurance

Example of Articulating and Aligning the Program Vision to Institutional Strategies:

|

Program Vision Statement: Develop an online program that will provide students with interdisciplinary knowledge about artificial intelligence and prepare them to work in the IT sector. |

|

| Institutional Strategy: | Alignment to Vision: |

| Strategic Mandate Agreement (SMA) | Selected IT programs are an area of institutional approved focus and this program topic is included as an IT program |

| Digital & eLearning Strategy | The strategy identifies a target for increasing the number of online programs and this supports that goal |

| President’s Target for New Programs | There is an institutional target for the creation of a specific number of new programs each year and this supports that goal |

| Ministry of Colleges and Universities (MCU) Funding Approval | Funding requests require a vision as part of the program rationale and this vision meets that requirement |

| Institutional Strategic Plan | The key goal of the strategic plan is to increase access to historically underrepresented populations and offering this program online in a flexible timetabling format will provide access to those unable to attend classes in person. |

Creating a Program Description

Using the information you created to this point, write a brief, informative description of the new program that provides high-level insight for those who need to understand it. This should be no more than one or two paragraphs that summarize the program and that can be modified for later use in websites, brochures, and other marketing documents. You will also use this for the New Program Proposal later in this module. In some cases, the program vision itself will satisfy the need for a program description, whereas in other instances it may need to be expanded slightly. Algonquin College provides some helpful tips for writing program descriptions:

Broadly speaking, the tone of all Program Descriptions is engaging and reader-friendly. Program Descriptions engage the audience by employing the following editorial tips:

- Use the active voice and present tense (avoid the use of the word “will”)

- Use personal pronouns to address readers directly (e.g., “you” and “yours”)

- Use simple sentence structure and concise language

- Use inclusive, gender-neutral language

(Algonquin College, n.d.)

Program Description Examples

➊ Major in Popular Music Studies at Western University

The BA (Major in Popular Music Studies) is a module unique to Western University that engages students with the interdisciplinary nature of the study of popular music. The program incorporates three dimensions:

- Practical subjects, including song writing and analysis of popular songs and recordings

- Recording practice

- Critical study of musical styles, recordings, artists, and genres in their broader historical and cultural contexts.

In addition to courses in popular music and culture, the program includes post-1945 popular music, musical theatre, jazz, and more advanced courses on indigenous music and music of the world, film studies, literature, and sociology. Introductory and advanced courses in song writing and desktop music production allow students to compose, produce, and record their own music (Western Music, n.d.).

➋ General BA in English at Queen’s University

When you study English online at Queen’s with this General BA, you’ll learn to read perceptively, analyze clearly, and communicate effectively. You’ll explore writers such as Shakespeare, Austen, and Bronte, but also engage with current forms such as graphic novels and works of contemporary writers (Queens University, n.d.).

➌ Oneida Language Immersion, Culture, and Teaching at Fanshawe College

The Oneida Language Immersion, Culture, and Teaching program is an Ontario College Advanced Diploma (Accelerated) offered in-community at the Oneida settlement, southwest of London, Ontario. This program includes immersive language learning that prepares students for a variety of language-related careers including teacher of On^yote’a:ka as a second language, translator, language consultant, language specialist or storyteller. The program’s unique structure supports the building of language skills and enables the immersive and cultural integration qualities of the curriculum. Students will learn best teaching practices such as classroom management, lesson planning and education theory, which will provide a pathway to further studies in teaching. The program is intensive by its very nature and requires a strong commitment from students to attend each lesson and take advantage of practice opportunities. Students may find employment in school boards, communities, government agencies, educational facilities and more (Fanshawe College, n.d.).

Considering Barriers to Online Program Development

You have now collaborated to create a vision, aligned it with strategies, and used all that information to draft a program description. Before moving to determine the resources required and the feasibility of the program, it’s useful to reflect on the challenges that might be faced. This will help inform what is needed in terms of resources to overcome the challenges in developing an online program. In the video below are some examples of challenges faced by others.

Online Program Development Resource Assessment

Determining costs and other resource needs requires collaboration with those who have the knowledge and expertise to provide accurate estimates. For example, the administrator of the Learning Management System (LMS) can provide information about any additional LMS costs associated with an online program, such as licensing. The Finance and Human Resource Departments can provide samples of costs for other online programs and resources, and the Information Technology (IT) Department can provide information about software that may already be supported or that will need to be purchased. Consultations are necessary to support an accurate cost assessment, and such collaboration will also legitimate the feasibility of the program. In the video below, two educational leaders discuss some of the main challenges and opportunities related to resourcing and sustaining online programs.

As you can see, from the video, articulating the vision for a new program naturally leads to questions about the necessary resources to realize that vision. If the vision is the “why,” then resources are the “who” and “what” in terms of the needs for creating the new online program. If you followed the SOAR process for visioning—or even if you used another approach—various resource needs may have been identified and discussed as part of creating the program vision. The workbook activity below will allow you to list those needs in preparation for a more detailed business plan in the next section on feasibility, including:

- Creating a list of what is necessary to develop the program: assessing resources in this section can be specific to program development needs or the resources for delivering the program itself. For example, developing the program may require hiring a subject matter expert to support the creation of program learning outcomes and course content, and delivering the program may require IT infrastructure or software investment in the educational technology stack.

- Identifying which resources on the checklist currently exist and which need to be acquired.

- Identifying costs for development and for the program itself (this can be used for the next unit on program feasibility)

- Starting to consider who you might need to hire as an additional resource and the cost associated with the hire. Use the interactive object below to click through a list of possible roles that might support your program development. Note that some of these roles may already exist at your institution and be available to work with you at no additional charge. Part of your feasibility planning will be to determine to what extent you need to budget for the necessary expertise and where it is available in kind.

Workbook Activity: Complete the list of required resources in the workbook for use in your New Program Proposal.

Sample:

| Required Resources | |

| Resource | Contact for Consultation/Information/Support |

| Subject matter experts to support costing of equipment and development of learning outcomes | Associate Dean, Department Administrator, or Human Resources to determine the cost for hiring |

| Full time or part-time faculty to develop course curriculum | Associate Dean, Department Administrator, or Human Resources to determine the cost for hiring |

| Software or technology infrastructure expense (e.g., simulation software, servers) | IT Administrator, LMS Administrator |

| Operational expense (e.g., consumables that are used for the program each time it is offered, software) | Department Administrator, Finance Department |

| Non-faculty human resource needs (e.g., lab technicians, teaching assistants, program coordinator) | Department Administrator, Human Resources Department |

| Marketing (e.g., recruiting, promotion items, advertising) | Marketing Department or Department Communications/Marketing |

| One-time start-up expenses (e.g., launch event, travel, professional development) | Marketing Department or Department Communications/Marketing |

| Library resources (e.g., purchase of new resources such as e-books, journal articles, software) | Librarian/s |

| Additional student service supports (e.g., specialized career service support, additional resources for accessibility, counselling, and advising resources) | Administrators in Student Services or the International Office depending on needs |

| Other: | |

Unit Resources

Unit Resources

The use of evidence that contributes to decision-making about particular problems or issues about best use of resources within institutions and across the healthcare system.

from Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (2006). Weighing Up the Evidence. Making evidence-informed guidance accurate, achievable, and acceptable. A summary of the workshop held on September 29, 2005.

These are the eLearning Tools and software that will enable students to learn online, for example, the Learning Management System and any plug-in tools—such as audience response systems, Web Conferencing software, and Assessment software—as well as the hardware required for the stack to operate.