8.3 Developing Training Programs

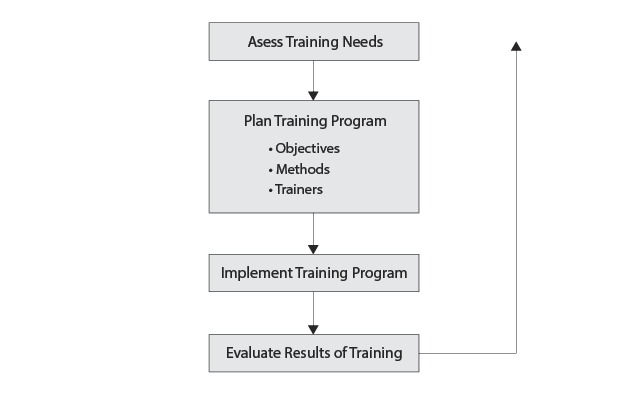

Instructional Design is a process of systematically developing training to meet particular goals and objectives. Figure 8.1 provides an overview of the process. The process begins by conducting a needs assessment to determine what kind of training is required to meet organizational goals. Organizational goals for health and safety training often include meeting legislative requirements or seeking to reduce injury rates, enhancing (or remediating!) the organization’s reputation for safety, or qualifying for workers’ compensation premium rebates. Employers seek to meet these goals by changing workers’ knowledge, skills, or behaviours via training.

Identifying specific organizational goals often clarifies who needs to be trained and the nature of the training that is required. Continuing with the example started in the last section, an organization seeking to meet its obligation to provide WHMIS training would train those workers who will work with hazardous materials. The content of the training will be shaped by which hazardous materials were used in the workplace and the selected control strategies. Whether a workplace would retrain workers who had previously received training might depend upon the nature of the hazard (which may have changed over time), the control strategies adopted (e.g., some PPE may require workers to undergo periodic retraining), and the additional cost (if any) of the retraining.

The question of cost reminds us that a needs assessment is not an entirely technical undertaking. What training is needed is not always perfectly clear, and those responsible for designing training can legitimately choose among different training options. For example, do workers with no responsibility for containing chemical spills require this training? This discretion over how to train is exercised in a particular economic and political context. Employers in capitalist economies are influenced by the profit imperative either directly or indirectly (in the case of public and non-profit sectors), which often causes them to seek to minimize labour costs (which include the cost of training). This often means that a needs assessment entails a cost-benefit analysis of the training, which may shape the kind of training employers choose to provide.

Figure 8.1 The instructional design process

Once the broad organizational goals of training have been identified, our attention then shifts to planning the training program, including developing the specific training objectives and methods and selecting trainers. Training objectives typically identify what the worker is expected to know or be able to do at the end of the training and establish some level of acceptable post-training performance. Training objectives may also help employers identify materials (e.g., MSDSs, PPE, administrative procedures) required for workers to apply the training in the workplace. Carrying on with the earlier WHMIS training example, workers might be expected to identify the ways in which each type of hazardous material can cause harm and be able to perform any physical skills associated with the control strategy adopted for each hazard (e.g., monitoring ambient levels of a gas). They might also be expected to always comply with the control strategies when working with the materials after the training and face periodic evaluation of their compliance and potential sanction for non-compliance.

After the training objectives have been established, it becomes necessary to determine what training methods will be used to accomplish the objectives. Most of us have sat through classroom-based training at some point, and online training is becoming increasingly common because its cost is relatively low and it can be offered when it is convenient to the learner. Lecture- or demonstration-style training may not be the most effective way to teach OHS skills and procedures. Experiential training (e.g., hands-on training or real-world simulations) may be more effective. It may also take more than a single demonstration or opportunity to practice for workers to become proficient at OHS skills and then integrate them into their work practices.

The final step in planning the training program is to select the trainer. Training may be provided by staff members or contracted to an outside provider. This decision is often based upon the required expertise (e.g., being licensed to provide training for particular kinds of equipment) and the cost. A common pitfall in OHS training is selecting a provider (who often has a pre-packaged program) before determining the training objectives and methods. This approach may reduce the effectiveness of the training, as usually training is not a one-size-fits-all proposition.

Techniques of delivering training are beyond the scope of this book, although the discussion above provides some examples of different delivery strategies. After the training has been delivered, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of the training. There are four types of training outcomes that can be assessed and listed in ascending order of measurement difficulty:

- Reaction: Trainees’ satisfaction with the training venue, content, and activities is easy to assess (e.g., using a questionnaire). This information may be used to improve participants’ subjective experience of future training events but does little to assess the degree to which the training has met the training objectives.

- Learning: It is possible to measure the knowledge and skills trainees gained from the training through testing (e.g., multiple-choice quizzes, demonstrations). These measures are useful at measuring short-term outcomes of training. Learning outcomes can also be assessed partway through a longer training program in order to identify which aspects of the training require reinforcement or additional practice.

- Behaviour: OHS training often seeks to alter trainees’ behaviour, so measuring behavioural change in the workplace over time may be a useful assessment. This can be done through observation or by reference to indicators of desired behaviours (e.g., monitoring workers’ level of exposure to radiation).

- Results: The purpose of training may be to affect overall organizational performance (e.g., lower injury rates). When assessing such outcomes, it is important to be mindful of non-training factors that may affect organizational results and that a positive outcome may not be due to the training itself.

Behaviour-based safety systems

Training is often said to be an effective means of reducing the incidence of workplace injury. For example, training workers to work safely is a key component of behaviour based safety (BBS), a popular approach to OHS among employers. BBS views the workplace as a venue of measurable behaviour that can be properly shaped to prevent injuries.[1] As its name implies, BBS draws heavily on a behaviourist view of learning and focuses on modifying worker behaviour via training-reinforced positive and negative feedback. For example, safety metrics (e.g., number of days without a time-loss injury) may be publicly posted and linked to rewards (e.g., cash bonuses or workplace events such as free pizza lunches). Such rewards certainly can shape worker behaviour. It is unclear, however, if these rewards cause workers to work more safely or simply alter their injury-reporting behaviours.

BBS focuses attention on observable behaviours, most of which are performed by workers. This approach tends to narrow the scope of safety inquiry, neglecting root causes of injuries and factors directly within employer control. In this way, BBS constructs injuries as the result of worker incompetence, inattentiveness, and carelessness, often (and incorrectly) claiming that up to 90% of injuries are caused by unsafe acts.[2] Ignored in this approach to incident prevention are factors that are harder to observe, such as the (un)availability of safety equipment, unsafe production processes and job designs, pressure to work faster, and the employer failing to remediate known hazards.

Moreover, the solutions that flow from BBS tend to focus on modifying worker behaviour (via less effective forms of hazard control, such as administrative controls, PPE, and worker training) rather than remedying the hazardous condition through elimination, substitution, or engineering controls. In this way, BBS leads to an entrenchment of a workplace culture of blaming the worker for mishaps. The United Steelworkers of America have provided a trenchant critique of BBS, showing that it facilitates greater management control over workers while providing “no mechanism for the workers to discipline management” for inadequate safety protection.[3]

BBS is a concrete example of how the different views of employers and workers about injury prevention can play out in the workplace. When conducting a needs assessment, it is important for OHS practitioners to be cognizant of the political context in which the training is occurring. This contextual awareness may also help identify the potential for worker resistance to the content or format of training based upon their workplace interests.

Assessment activities are often determined during the design phase. This approach tends to most closely align assessment with the training objectives and ensure assessment is appropriate for the chosen training method. Concluding the WHMIS example, if the organizational goal is meeting (and being seen to meet) legislative requirements around hazardous materials, this goal can be met by demonstrating that workers received the training. Assessing workers’ learning and behaviour might tell both the employer and the workers important things about the effectiveness of the training at imparting knowledge and skills and altering behaviour. That said, cost considerations might affect the degree to which the achievement of training objectives get measured.

- Geller S. (2001). Behavior-based safety in industry: Realizing the large-scale potential of psychology to promote human welfare. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 10(2), 87–105. ↵

- Frederick, J., & Lessin, N. (2000). Blame the worker: The rise of behavioral-based safety programs. Multinational Monitor, 21(11), 10–14. ↵

- United Steelworkers. (n.d.). The Steelworkers Perspective on Behavioral Safety. Pittsburgh: Author, p. 5. http://assets.usw.org/resources/hse/Resources/uswbbs.pdf ↵

The process of systematically developing training to meet particular goals and objectives.

A process to determine what kind of training is required to meet organizational goals.

The outcome(s) an organization expects to realize from training.

What the worker is expected to know or be able to do or how they will act as a consequence of the training, often expressed as some level of acceptable post-training performance.

The strategies and techniques used to meet training objectives.

An approach to OHS that views the workplace as a venue of measurable behaviour that can be shaped via feedback to prevent injuries.