11.2 Realities of Workplace Under Capitalism

Throughout this book, we have considered how the power imbalance in Canadian workplaces—an imbalance that favours employers and allows them to advance their interests at the expense of workers’ interests—affects OHS policy and practice. We have already discussed many of the mechanisms that benefit employers, from the careless-worker myth to behaviour-based safety. This section extends this analysis to consider how contemporary OHS arrangements developed and how they have slowly eroded the role of workers in workplace safety.

Today, OHS is a highly technical and highly professionalized field. Safety professionals are often extensively trained, and research has improved the effectiveness of hazard recognition, assessment, and control tools. OHS is also a multi-million dollar industry. Employers hire consultants and safety specialists to provide a wide range of services, from training to technical monitoring and control to designing safety systems. Most industries have developed industry safety associations (more on this below), both to offer many of these services and to lobby governments on employers’ behalf.

Safety was not always a sophisticated industry. The modern OHS movement arose out of worker activism and (sometimes illegal) workplace action that forced employers and governments to address safety concerns. During the 1960s, a series of wildcat strikes in industrial plants across Canada raised the profile of OHS issues.[1] In the 1970s and 1980s, worker safety activists formed a network that pushed for better hazard control, trained workers to protect their health, and forced legislative change that created the contemporary health and safety regime.[2] Most often the activism was conducted in the face of opposition from both employers and government.[3]

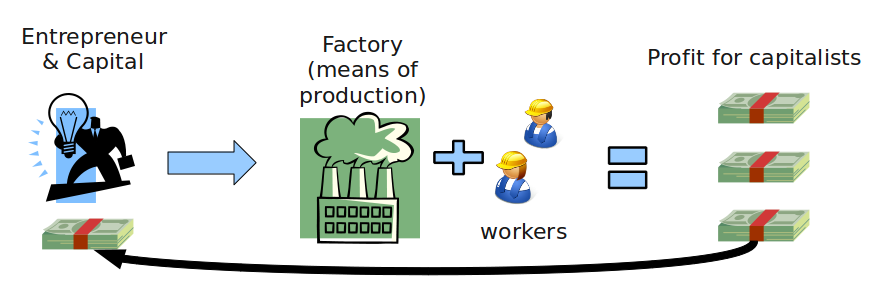

Despite government reluctance to take action on OHS, early government regulators recognized and enacted legislation and enforcement practices designed to mitigate the power imbalance in the workplace. For example, OHS pioneer Robert Sass, who wrote Canada’s first OHS legislation (in Saskatchewan) and was the architect of the three worker rights (i.e., the rights to know, participate, and refuse), argued that employer and state resistance to improving workplace safety was driven by the profit imperative of capitalism.[4] This view was consistent with historians’ understanding of government and employer safety efforts in the late 19th and early 20th century, which were designed to ensure that unsafe workplaces did not compromise employers’ ability to make a profit.[5] It is useful to remind ourselves that the profit imperative is also present, somewhat indirectly, in public and non-profit sector workplaces as well.

Over the last 30 years, the link between OHS and the broader struggle between worker and employer interests in the workplace has been obscured by employer efforts to professionalize safety. Professionalized OHS entails segregating safety issues from the rest of work by transforming OHS into a “neutral” practice of objectively measuring and correcting hazards. Employers benefit from narrowing OHS to a merely technical undertaking because, for example, it allows them to address safety issues with inexpensive (and often inadequate) controls (such as issuing workers PPE) rather than altering the work process to eliminate or at least control workers’ exposure to the hazard. This narrow approach has also legitimized employer’s cost-benefit analysis in OHS, as discussed in Box 11.1. Overall, this professionalization has rendered invisible the conflicting safety interests of employers and workers.

In professionalized OHS, safety becomes another tool with which the employer can control how the worker will perform their work. Safety becomes a monologue by the employer, rather than the dialogue between workers and employers that was envisioned by Sass and others. The implications of this change are evident in most workplaces across all sectors. There is little discussion between workers and their supervisors about how to control hazards. There is little debate about whether PPE is sufficient or whether something more is required. And the experiences of workers like Andrea MacPhee-Lay tell us what can happen when a worker speaks up about safety.

The Consequences of cost-benefit analysis in OHS

The Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (that province’s WCB) partnered with the Ontario division of the Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters association to produce a health and safety guidebook for employers, entitled Business Results through Health and Safety. The guide makes the economic case for safety:

In 1999 there were over 100,000 lost time injuries and occupational illnesses in Ontario workplaces. Over $2.6 billion (including administrative costs) was paid in compensation claims to injured and ill employees. In addition, indirect costs associated with workplace accidents and illness are conservatively estimated to be at least 4 times the direct costs. Together with direct costs this means there was over a $12 billion drain on Ontario productivity in 1999, and a loss of competitive advantage.[6]

The average workplace lost time injury in Ontario costs over $59,000. Surprised? The average lost time workers compensation claim cost is over $11,771, and other costs add up more quickly than most people realize. Property damage, lost production, manager and supervisor time due to an accident and with the injured person, costs to comply with Ministry of Labour orders, and the employee’s lower productivity while on light duty; the source of additional costs is extensive. . . . If your profit margin is 10%, it requires $590,000 in sales to produce $59,000 of profit. . . . A reduction of a lost time injury costing $59,000 has the equivalent profit effect as increasing sales by $590,000 at a 10% profit margin.[7]

These excerpts represent the classic economic argument for health and safety: safety pays. While this argument may persuade some employers to address safety issues, there is an unstated corollary: workplace safety should only be improved when it reduces costs and increases profit. The idea that safety should not be pursued if it costs too much is a pivotally important implication of this cost-benefit approach to OHS.

In this view, safety becomes a commodity that an employer can purchase so long as it has utility. Implied in this reasoning is that some degree of unsafe work is acceptable and that it is an employer’s right to decide the level of (un)safety experienced by workers. That OHS—and the human beings that OHS protects—might have intrinsic value is simply ignored in cost-benefit analyses. In this construction of workplace safety, safety is framed as a commodity.

This way of conceiving of occupational safety and health . . . reinforces the cognitive tendency to believe individuals make free choices in market transactions, including the choice to work in jobs that have greater safety and health risks. Second, it crowds out the democratic values that led to earlier legislation protecting workers. An economic point of view treats workplace safety and health policy as an issue to be determined using market values, rather than as a matter for democratic deliberation.[8]

Framing health and safety as a way to increase profits may on the surface be an appealing strategy for engaging employers. Yet this cost-benefit approach to OHS also legitimizes danger and ill health and undermines the workers’ role in achieving safe workplaces.

Another consequence of professionalized OHS is that the safety role of unions is diminished. When safety is seen as part of the employment relationship, the union has a legitimate role to play in safety (e.g., training workers, inspecting workplaces, raising issues on JHSCs) and safety is a condition of work that can be negotiated. Indeed, many unions appoint or elect a safety representative who engages with the employer to negotiate appropriate safety provisions. When employers outsource OHS to consultants and broadly treat it as a function separate from the work process, the union loses some of its ability to shape workplace safety.

The sidelining of unions is more than just a theoretical labour relations problem. Unions make workplaces safer. Unionized workplaces have lower incident and injury rates than non-union workplaces.[9] Unionized workers are also more likely to hold beliefs—for example, that taking risks is not part of their job—that contribute to safer work practices.[10] Unionized workplaces are safer due to a combination of better training (that teaches workers how to use their safety rights to make the workplace safer[11]), a more formalized process for worker participation (such as safety meetings and JHSCs[12]), and less fear among unionized workers of repercussions for exercising their rights.

The safety effect of unions demonstrates that OHS is most effective when workers are actively engaged in dialogue about safety and empowered to make change. This more democratic approach to safety runs counter to employers’ interests in maintaining control over the work process. Thus employers use their greater power in the workplace to shape OHS in ways that diminish workers’ roles. The reality of workplace safety under capitalism is that employers and workers want different (and often mutually exclusive) types of OHS, and over the past 30 years employers have slowly been winning this struggle.

- Richardson, B., & Newman, D. (1993). Our health is not for sale. Ottawa: National Film Board of Canada. ↵

- Storey, R. (2005). Activism and the making of occupational health and safety law in Ontario, 1960s–1980. Policy and Practice in Occupational Health and Safety, 1, 41–68. ↵

- Storey, R., & Lewchuk, W. (2000). From Dust to DUST to dust: Asbestos and the struggle for worker health and safety at Bendix Automotive. Labour/Le Travail, 45, 103–140. ↵

- Sass, R. (1986). The workers’ right to know, participate and refuse hazardous work: A manifesto right. Journal of Business Ethics, 5(2), 129–136; Sass, R. (1989). The implications of work organization for occupational health policy: The case of Canada. International Journal of Health Services, 19(1), 157–173. ↵

- Tucker, E. (1990). Administering danger in the workplace: The law and politics of occupational health and safety regulation in Ontario, 1850–1914. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ↵

- Ontario Workplace Safety & Insurance Board & Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, Ontario Division (2001). Business Results Through Health and Safety. Toronto: WSIB, p. vi. ↵

- Ibid., p. ix. ↵

- Shapiro, S. (2014). Dying at work: Political discourse and occupational safety and health. Wake Forest Law Review, 49, 831–847, pp. 832–833. ↵

- Yi, K. H., Cho, H. H. & Kim, J. (2011). An empirical analysis on labor unions and occupational safety and health committees’ activity, and their relation to the changes in occupational injury and illness rate. Safety and Health at Work, 2(4), 321–327. ↵

- Gillena, M., Baltz, D., Gassel, M., Kirsch, L., & Vaccaro, D. (2002). Perceived safety climate, job demands, and coworker support among union and nonunion injured construction workers. Journal of Safety Research, 33(1), 33–51. ↵

- Hilyer, B., Leviton, L., Overman, L., & Mukherjee, S. (2000). A union-initiated safety training program leads to improved workplace safety. Labour Studies Journal, 24(4), 53–66. ↵

- Yi, K. H., Cho, H. H., & Kim, J. (2011). An empirical analysis on labor unions and occupational safety and health committees’ activity, and their relation to the changes in occupational injury and illness rate. Safety and Health at Work, 2(4), 321–327. ↵