10.1 Disability Management

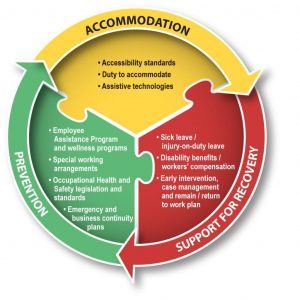

Disability management is a set of employer practices designed to prevent or reduce workplace disability and assist workers in recovering normal functioning as quickly as and to the maximum degree possible. In sections that follow, we’ll examine each of the three interrelated aspects of disability management:

| Prevention | Employers may seek to prevent injuries and illnesses that give rise to disabilities through injury prevention efforts as well as employee assistance and wellness programs. |

| Accommodation | Workers who have disabilities may require accommodation. This may include assistive technologies and modifications to work, work processes, and the workplace. |

| Recovery | Some disabilities are temporary in nature. Sick leave, modified work, disability benefits (including workers’ compensation), and return to work programs can assist workers during the period of time required for them to recover.[1] |

Before discussing disability management, it is useful to consider what the term disability means. Disability is often discussed as a characteristic of a worker (i.e., the worker is disabled). While a worker may indeed have an impairment, it is important to remember that it is the workplace context that turns the impairment into a disability. See more information in the box below.

Conflating impairment and disability

It is useful to be mindful of how we use the term disability. At a very basic level, disability means the condition of being unable to perform a function or task as a consequence of a physical or mental impairment. That definition seems pretty straightforward. In this case, being unable to perform a function is only meaningful if performing the function is an expectation of a situation. What this means is that the existence of impairment (i.e., a cognitive or physical difference) does not cause a disability. Rather, it is the nature of the tasks in the workplace that turn impairment into a disability.

For example, pretend that your sense of smell is very limited. Is that olfactory impairment a disability? If you were a gas fitter, it might well be considered a disability because being able to smell a gas leak is an expectation of the job (even though there are other ways to detect natural gas). In most other circumstances, few people would consider an impaired sense of smell a disability. Thus the work context turns the impairment into a disability. Impairments are, on their own, not necessarily troublesome, tragic, or disabling. Further, altering the context (e.g., modifying work) can eliminate the disability even though the impairment remains.

One of the ways disability and impairment are socially constructed is that we often associate them with traits that have some form of observable manifestation. It is important to remember that impairment and disability are not always visible or obvious. Much impairment is difficult to casually observe (e.g., diabetes or epilepsy). Cognitive and mental conditions can be particularly difficult to identify. Others can be cloaked through treatment (e.g., prostheses, medication). Society may overlook impairments that are less observable, and thus may be less likely to implement appropriate accommodations to address them.

It is also important to be mindful of the tendency to conflate illness and disability. Illness often entails discomfort, and we seek medical intervention to either resolve the underlying cause or treat the symptoms. Sometimes, illness can cause an impairment that, in specific workplace circumstances, creates a disability. Yet, in most cases, disability and impairment require neither medical supervision nor intervention. In this way, impairment and disability are not questions of health or ill health.[2]

Disability management is often said to minimize the cost of disability to employers.[3] These practices also ensure that employers meet their duty to accommodate. Human rights legislation requires employers to avoid discriminatory workplace practices. This chapter focuses specifically on employers’ obligation to accommodate workers with temporary or permanent physical or mental injuries, regardless of whether the impairment was caused by a workplace injury.

Employers’ duty to accommodate requires employers to alter work, work practices, or the workplace in order to allow workers with disabilities to perform meaningful work. The duty to accommodate requires employers to make any necessary efforts to accommodate the worker’s disability-related needs up to the point of undue hardship. The threshold of undue hardship varies from workplace to workplace. To claim undue hardship, typically, an employer is required to demonstrate that an accommodation is economically unsustainable, interferes with a legitimate operational requirement, or poses a health-and-safety threat.[4] In these circumstances, an employer is still required to provide whatever accommodation is possible short of undue hardship.

Why Have an Approach to Job Accommodation by Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB)

Undue Hardship – the Ontario Human Rights Commission

- Government of Canada. (2011). Fundamentals of disability management. Ottawa: Author. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/psm-fpfm/ve/dee/dmi-igi/fun-fon/intro-eng.asp ↵

- Stone, S. (2008). Resisting an illness label: Disability, impairment and illness. In P. Moss & K. Teghtsoonian (Eds.), Contesting illness: Processes and practice (pp. 201–217). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ↵

- Tompa, E., de Oliveira, C., Dolinschi, R., & Irvin, E. (2008). A systematic review of disability management interventions with economic evaluations. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 18(1), 16–26. ↵

- Manitoba Human Rights Commission. (2010). Reasonable accommodation. http://www.manitobahumanrights.ca/publications/guidelines/reasonable_accommodation.html ↵

A set of employer practices designed to prevent or reduce workplace disability and help workers to recover normal functioning as quickly and to the maximum degree possible.

The condition of being unable to perform a function or task as a consequence of a physical or mental impairment.

A cognitive or physical difference that, in a specific context, may give rise to a disability.

Employers’ legal obligation to alter work, work practices, or the workplace to the point of undue hardship in order to allow workers with disabilities to perform meaningful work.

The point at which an accommodation is economically unsustainable, interferes with a legitimate operational requirement, or poses a health-and-safety threat.