7.4 Women’s Movement

WATCH FILM

Hershman-Leeson, Lynn, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Judy Chicago, Marina Abramovic, Miranda July, and Yoko Ono. Women Art Revolution. , 2019. Internet resource. https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/5322096?vp=banq

Please Read

Jones, Amelia. The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. London: Routldge, 2010. Print. https://archive.org/details/feminismvisualcu0000unse_s9h4/mode/2up

Chapter 7 John Berger pp 49 – 52

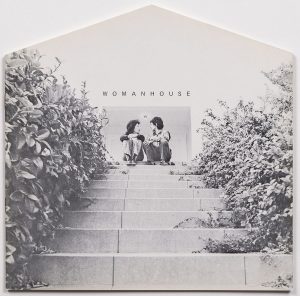

Chapter 8 Judy Chicago & Miriam Shapiro pp. 53 – 56

http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/yoko-ono-betye-saar-eva-hesse-alice-neel-feminism-motherhood-and-art/

Audrey Flack (editing in process)

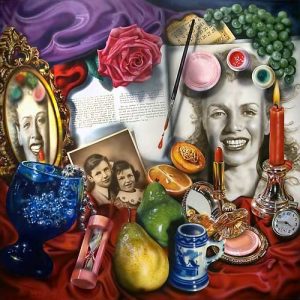

Audrey Flack was born in 1931, in New York City to a middle-class family with the expectation, as with most women of her generation and culture, to follow societal rules placed upon women[2]. In addition to having her own family, Flack was determined to be a great artist and became the first woman artist mentioned in an American art history textbook. Educated in art theory and practice from Cooper Union, Yale, and the New York Society of Art, additionally, Flack teaches across multiple Universities in the United States and lectures and exhibits internationally. In the 1970s, she reinforced the idea female artists could fit into a newly-generated and binding theory of feminism in art while challenging male-dominated art practices established in the 1950s and 1960s. Referencing this era in Marilyn (Vanitas) (1977) (fig.), Audrey Flack depicts the young Norma Jeane Baker before her self-initiated transformation as silver-screen icon Marilyn Monroe. Within the composition, Flack acknowledges parallels between her youth and that of Norma Jeane Baker. With the decision to invoke individual and social convictions as an artist, daughter, mother, and woman by sticking to these convictions Flack began to create work that transcends time.

During the 1930s and 40s, American artists were financially subsidized by the federal government and promoted by the federal art project. Amid the post-war boom of the 1950s, artists no longer wanted to operate within an art-for-arts sake doctrine[3]. These same artists whose careers began through government sponsorship schemes became leaders of the abstract expressionism movement with the notable exclusion however of most female artists. Female artists unable to enter into the male-dominated art world were pushed back to their homes and male artists stood at the forefront of art.[4]

The abstract expressionism movement among men was the focus of American modernism and it was seen by Flack as an elitist attitude towards art production, This type of attitude was used to impose further constraints on women students and professors in the most sought-after art institutions. Flack was of no exception, regardless, as a student of modernist Josef Albers, a leading aspect of her scholarly painting follows the doctrine of abstract expressionism by the strong use of colour, theories of vision, and an intuitive narrative.

Flack challenges contemporary masculine theories of art and art education and during her studies, Flack transformed her approach to academic painting from purely abstract to include figurative works.[7] Flack borrowed painterly tools from Dutch ‘vanitas’ still lives of the seventeenth century; specifically by including the study of works by Rembrandt, and two women artists, Louisa Roldan and Maria van Oosterwyck. [8]”. Flack is also inspired by Spanish baroque sculpture, nineteenth-century portraiture, abstract expressionism, pop art, photography, philosophical concepts on the nature of life and death, and psychoanalytical constructs, in doing so, Flack created new forms of painting, photorealism, and super realism[11].

Audrey Flack’s first photorealist work, as first coined by long time champion of her work, Louis K Meisel[15], was created in 1964, “Kennedy Motorcade” (fig.2), in which Flack painted by directly referencing a photograph from a magazine depicting the moment just before the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Her painting was autobiographical and invoked transcendence through a coming-of-age theme. Her contemporary male artists witnessed her work in photorealism, put their own spin on the execution of the style, and became more revered within the art world.

Audrey Flack changed her focus to public art sculpture in the 1980s. For over 20 years, Flack created sculptural works, infused with healing energies as found when revering the archetype of the goddess and the idea of a positive role model. Flack designs a multitude of sculptural programs, from those you can hold in your hand to large monumental Public civic works. Not binding herself to conventional stereotypes of women, combining historical theories on art-making, confronting traditional views on women’s role in society, and the use of the female body to invoke allegories of universal concepts such as strength, peace, and love, Flack has created a vast work of genius to mirror her own great achievements and has created a universally connective theory of art.

For further study:

The Gorilla Girls (https://boisestate.pressbooks.pub/thecreativespirit/chapter/chapter-15-globalism-and-identity/)

In 1985, a group of vigilantes wearing gorilla masks took to the streets. Armed with wheat paste and posters, the Guerrilla Girls, as they called themselves, set out to shame the art world for its underrepresentation of women artists. Their posters, in the words of one critic “were rude; they named names and they printed statistics. They embarrassed people. In other words, they worked.” In addition to posters (now highly-valued works of art), billboards, performances, protests, lectures, installations, and limited-edition prints make up the Guerrilla Girls’ varied oeuvre. Their unorthodox tactics were instrumental in making progress. The group is still going strong, reminding the art world that it still has a long way to go. Referring to themselves as “the conscience of the art world,” wherever discrimination lurks, the Guerrilla Girls are likely to strike again.

As their reputation has grown, they have encompassed targets beyond the art sphere, like Hollywood, right wing politicians, and same-sex marriage. They have collaborated with institutions that once shunned them, including the Tate Modern and MoMA, and yet their tactics remain as radical as ever. In a 2012 interview they revealed, “We’ve been working on a weapon, an estrogen bomb…If you drop it, the men will drop their guns and start hugging each other. They’ll say, ‘Why don’t we clean this place up?’ In the end, we encourage people to send their extra estrogen pills to Karl Rove; he needs a little more estrogen.”

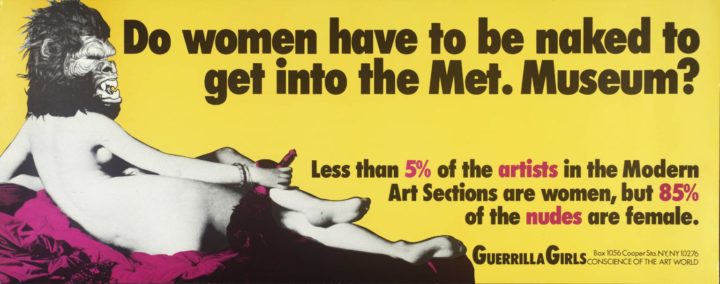

The 1989 piece titled “Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?” addresses the sexualization of women’s bodies in highly regarded paintings and artwork, and how ironically, “85% of the nudes are female” in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (an art museum in New York City), while “less than 5% of the artists in the modern art section are female”.

“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?” is notable for many reasons. Firstly, this is one of the first posters produced by the Guerrilla Girls’ that uses a variety of eye-catching colors as opposed to previous posters which were black and white, or utilized one color. This piece uses grayscale in addition to the bright colors pink and yellow, which almost create the illusion of vibration when juxtaposed. Secondly, up until this point the Guerrilla Girls’ posters made effective use of text based posters. But this poster incorporates imagery in addition to statics the Guerrilla Girls gathered while spending a day surveying the Met. They parodied a famous nude painting of a woman, La Grande Odalisque by Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, by taking the naked figure laying back in a relaxed position and placing a gorilla head over her face. Third, it really showed the boldness and passion for equal representation that the Guerrilla Girls possessed, as they went after the Met with the intention of shaming and humiliating such a prestigious art institution.

This poster also demonstrated their advertisement minded design in their choice of colors to get people’s attention, the bold typeface used, and use of color text to emphasize important elements of the statistics. Making it even more advertisement-like, the Guerrilla Girls paid for the poster put on the sides of New York City buses in the advertising spaces, until an outraged public caused the bus companies to disallow it from being shown. People were shocked, as they deemed the figure indecent and suggestive.

The work has been described as “iconic”(Seiferle), as it encompasses the style of the Guerrilla Girls: humor, use of facts and statistics, and advertisement style that can be found in so many of their works.

Sources Cited:

Manchester, Elizabeth. “Do women have to be naked to get Into the Met.Musem?.” Tate.org.uk, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guerrilla-girls-do-women-have-to-be-naked-to-get-into-the-met-museum-p78793.

Seiferle, Rebecca. “The Guerrilla Girls Artist Overview and Analysis.” TheArtStory.org, http://www.theartstory.org/artist-guerrilla-girls.htm.

Source: https://go.distance.ncsu.edu/gd203/?p=24873 Guerilla Girls