1.6 Colonial and Federal Design – USA

Please Read

Thomas Jefferson and his design of Monticello

https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Monticello

Over a period of more than forty years, between approximately 1767 and 1809, Thomas Jefferson designed, constructed, and renovated the house and gardens of his plantation home, Monticello [Fig. 1]. Located on a mountaintop southwest of Charlottesville in the Piedmont region of Virginia, the site was part of the 5,000-acre property in the Rivanna River district that he inherited from his father, Peter Jefferson, in 1757.[1]

Jefferson began planning Monticello in 1767, and construction began two years later. He drew heavily from Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture (1570) when designing the first version of his neoclassical house, a six-room structure featuring a two-story portico at the entrance [Fig. 2]. In an architectural memorandum that he wrote in 1769, for example, Jefferson recorded specific figures from Palladio’s text as well as from James Gibb’s Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1738), to which he referred during the construction of Monticello.[2] He held copies of both architectural treatises as part of his extensive personal library, which contained a significant collection of architecture and landscape design literature.[3] On November 26, 1770, Jefferson moved from Shadwell, his childhood home in Albemarle County, Virginia, to Monticello, occupying the top floor of the recently completed South Pavilion, the first brick building to be constructed on the property.[4] In 1782 the French Major General François-Jean Beauvoir, Marquis de Chastellux, an early visitor to Monticello, wrote that Jefferson was “the architect, and often one of the workmen” on the project and described the house—then still in progress—as “very elegant,” proclaiming “Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the fine arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather” (view text). By the summer of 1784, when Jefferson departed for Paris to serve as minister to France, the exterior of the first house at Monticello was largely complete but the interior remained unfinished.[5]

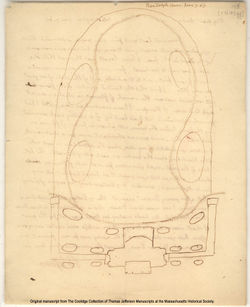

Whereas much is known about the construction of the dwelling during this initial phase, the landscape design during this period is less well understood. On May 15, 1768, Jefferson recorded in his Account Book that he had contracted with John Moore to clear and level 250 square feet of the mountaintop before Christmas, so that construction on the new house could begin the following year. By by summer of 1769, Jefferson had planted fruit trees in an orchard on the southeast side of the mountain and begun also begun preparations for a kitchen garden. A park with a circumference measuring 1,850 yards had been cleared on the north side of the mountain by September. Work on the first (or uppermost) of four roundabouts—roads that encircled the mountain at different elevations—began by November 1772. The roundabouts were connected to one another by roads that cut across the mountainside obliquely, as seen in this 1809 survey by Jefferson of the mountaintop [Fig. 3].[6]

Jefferson also recorded an elaborate landscaping plan for Monticello in his Account Book of 1771, but much of the design was never realized. In the plan, he called for the establishment of a burial ground with a “small Gothic temple of antique appearance” and the construction of a temple or grotto by the spring on the north side of the property. He also planned to thin the trees throughout the grounds and “intersperse Jessamine, honeysuckle, sweetbriar, and . . . hardy flowers” (view text).[7] Two early plans by Jefferson of the house and surrounding grounds indicate that he intended to create rectangular flower beds on the west side of the mansion and a semicircular arrangement of trees on the east side, but these features were not added until more than three decades later [Figs. 4–5]. Additional clues about Jefferson’s planting activities during these early years are provided in his Garden Book, which he maintained between 1766 and 1824. According to Jefferson’s records, various trees and flowers had been planted before he departed for Europe in 1784. This suggests the presence of flower beds near the house, although their exact location is undetermined.[8]

Jefferson cultivated a wide variety of fruits and vegetables at Monticello, planting an orchard, as noted above, as early as 1768 and a vegetable garden and vineyards by 1774. Under the guidance of Filippo Mazzei (1730–1816)—a Florentine horticulturalist and wine merchant who befriended Jefferson and settled in Albemarle County in 1773—Jefferson hired professional Italian gardeners Antonio Giannini and Giovanni da Prato to oversee the care of his fruit trees and vineyard.[9] Enslaved gardeners such as George Granger Sr., carried out much of the day-to-day work caring for the “orchards, grasses &c.”[10]

The five years that Jefferson spent abroad had a significant impact on his views of domestic architecture and landscape design.[11] During a visit to England in April 1786, Jefferson, accompanied by John Adams (1735–1826), visited sixteen English gardens, using Thomas Whateley’s Observations on Modern Gardening (1770) as his guide, and he recorded his impressions in his travel diary.[12] Jefferson apparently disliked the more formal gardens he visited, complaining, for example, that Chiswick House “shows still too much of art” and that the gardens at Hampton Court Palace were “old fashioned.” He preferred the style of the gardens at Esher Place, remarking that the clumps of trees “balance finely–a most lovely mixture of concave and convex.”[13]

Jefferson returned from Europe in 1789, eager to transform Monticello according to his new ideas. In a letter to Angelica Schuyler Church (1756–1814), written just before he departed for Virginia, Jefferson wrote that he looked forward to being “liberated from the hated occupations of politics” so that he could turn his attention back to Monticello: “I have my house to build, my fields to form, and to watch for the happiness of those who labor for mine” (view text). However, just a few months after landing in the United States, President George Washington appointed Jefferson the first U.S. secretary of state, a position he held through 1793; the implementation of his new plans for Monticello would have to wait. Jefferson’s son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph (1768–1828), with the participation of Jefferson’s daughters Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836) and Mary Jefferson (1778–1804), directed basic farming and gardening activities at Monticello in Jefferson’s absence.[14]

Jefferson resigned as secretary of state in January 1794 and retired to Monticello. Lucia Stanton has argued that Jefferson was largely focused between 1794 and 1796 on reorganizing the plantation, dividing it into quarter farms—each with seven fields of forty acres—in a “quest for economy and efficiency.” Perhaps the most significant transformation during these years was Jefferson’s decision, in an effort to reverse soil exhaustion, to replace tobacco with wheat as the plantation’s primary cash crop. The switch greatly affected the living and working conditions of the approximately one hundred enslaved people who lived at Monticello during this period. Wheat demanded more land for cultivation than tobacco, and thus, Stanton argues, drawing on archaeological evidence, that the accommodations for many enslaved field workers changed from from close clusters of large multi-family dwellings located near the overseer’s house to smaller, single-family cabins located on “scattered sites on the fringes of cultivated lands.”[15] Jefferson also made some improvements to the ornamental landscape at Monticello during these years, hiring the professional Scottish gardener Robert Bailey in 1794 to assist in laying out the grounds.[16]

In 1796 Jefferson embarked on a major expansion and renovation of the neoclassical house that he would later term his “essay in Architecture”—a project that was informed by the modern domestic architecture he had seen while living in Europe (view text). Jefferson removed the upper story of the original house; extended the northeast front to include a large entrance hall, library, and three bedrooms; and completed a second level of bedrooms within the first floor so that the house appears to be only a single story from the outside. He also added a dome—a first in American domestic architecture—to the house in 1800, inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Rome. L-shaped dependency wings nestled into the hillside to the north and south of the mansion largely kept utilitarian areas of the house—such as the kitchen, dairy, washhouse, privy, and horse stalls—out of view. Above the dependency wings, Jefferson constructed nine-foot-wide raised terraces that provided open views of the landscape from the house. According to William L. Beiswanger, these L-shaped terraces recall the elevated walkways suggested by the Scottish theorist and critic Lord Kames (1696–1782) in his Elements of Criticism (1762), a work that Jefferson knew by 1771.[17] Other utilitarian spaces, including several slave quarters, servant quarters, storehouses, and skilled workshops (such as the joinery and weaving cottage), were located along Mulberry Row—a street named for the mulberry trees planted on either side of it—that was located about 200 feet southeast of the mansion.[18]

Following a visit to the estate in May 1796, Isaac Weld (1774–1856), an Irish travel writer, described the changes underway and predicted that Monticello “[would] be one of the most elegant private habitations in the United States” (view text). One of the features of the house noted by Weld was the addition of a greenhouse adjacent to Jefferson’s private apartments, situated where his study opened onto the Southeast Piazza. Writing to William Hamilton, owner of the Philadelphia estate The Woodlands, in 1808, Jefferson described his greenhouse as “only a piazza adjoining my study” and explained that he intended to use “it for nothing more than some oranges, Mimosa Farnesiana & a very few things of that kind” (view text). The piazza was apparently without a heating system, and, according to Beiswanger, “its success as a greenhouse was limited.” The space was multipurpose, and Jefferson even added a workbench in order to use the space as a small workshop. Although nothing remains of the aviary at Monticello, which Jefferson likely designed to house his pet mockingbirds, a brief description in Jefferson’s building notebook suggests that it too was located in the Southeast Piazza and that the floor of the cage was high enough to walk under.[19]

Between 1797 and 1809, Jefferson spent much of his time in Washington, DC, while serving first as vice president of the United States (1797–1801) and then as president (1801–1809). Renovations on the house at Monticello continued throughout Jefferson’s absence and were not completed until 1809. Jefferson waited to implement a second major round of improvements to Monticello’s landscape. On July 31, 1806, while in the midst of his second term as president of the United States, Jefferson wrote from Washington to Hamilton that “having decisively made up my mind for retirements at the end of my present terms, my views & attentions are all turned homewards” and noted that he would wait to improve the grounds “in the style of the English gardens” until his return to Monticello (view text). However, as early as 1804, Jefferson began to put his ideas to paper, penning his “General ideas for the improvement of Monticello” (view text). Jefferson’s plans aimed to improve the views from the house, intending to arrange lawns and clumps of trees to maximize vistas between the upper and lower roundabouts and to create a pleasure ground with a large grove of trees “broken by clumps of thicket.” He also wrote of his desire to create a ha-ha made of stone excavated from the nearby garden (likely to save costs) along Mulberry Row. The ha-ha, which surrounded the west lawn, was not completed until 1814.[20] In 1806 Jefferson sketched plans for the mountaintop, featuring a large grove northwest of the mansion; an expansion of the vegetable garden and orchard to the south of the house; and an oval lawn or “Level” on the west front [Fig. 6].

The expansion of the fruit and vegetable gardens was a major undertaking during these years. In 1807 Jefferson hired a crew of enslaved laborers from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to move approximately 200,000 cubic feet of Piedmont clay to expand and transform the existing vegetable garden into a 1,000-foot-long terraced vegetable garden. 5,000 tons of rocks were placed to retain the terraces, and the arduous work took three years to complete. During the years Jefferson lived in Washington, his daughter Martha, aided by the enslaved gardeners George Granger Sr., “Gardener John,” and Goliah, tended the vegetable garden at Monticello.[21] After an 1809 visit to the plantation, Margaret Bayard Smith (1778–1844) noted that there was still much work to be done on the vegetable garden and wrote that the view from the garden was “at present its greatest beauty.” Smith also observed that Jefferson kept all of his garden seeds “labeled and in the neatest order” in a closet (view text). 330 varieties of 99 species of vegetables and herbs were grown in this two-acre garden at Monticello, including species native to the hot climates of South and Central America, the Mediterranean, Africa, and the Middle East, and seeds that Jefferson acquired through the Lewis and Clark expedition.[22] According to Peter J. Hatch, Jefferson took advantage of the terraced microclimates to “grow more vegetables with significantly less skill or labor” than was required by a more traditional and refined English-style kitchen gardens like the one found at George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate.[23]

Thomas Jefferson also improved the fruit garden, comprising two small vineyards, berry squares, a small nursery, and the 400-tree South Orchard, located to the south of the vegetable garden. The orchard had been surrounded by a hedge of hawthorn bushes that Jefferson purchased from the nurseryman Thomas Main in Washington, DC, and shipped to Monticello in February 1806.[24] In 1809, workers erected a ten-foot chestnut board paling fence surrounding the vegetable and fruit gardens that could be locked to keep the produce out of the reach of animals, plantation workers, and unwanted guests.[25] On the north side of the mansion, a second orchard was planted with cider apples (to take advantage of this orchard’s relatively cooler temperatures) and peach trees.[26]

From Washington, Jefferson worked primarily with his granddaughter Anne Cary Randolph to design and care for the new oval flower beds that were installed in 1807–8 on the east and west fronts of the mansion and the flower border along the winding walk surrounding the lawn (view text) [Fig. 7]. Jefferson instructed the overseer Edmund Bacon that Wormley Hughes, an enslaved man who had been trained by Bailey and by 1806 had become the principal gardener at Monticello, should prepare the flower beds for planting (view text)[27] Many of the flower seeds and bulbs were procured by Jefferson from the Philadelphia nurseryman Bernard M’Mahon (view text).[28]

In 1808 Jefferson also sent Bacon instructions for an experimental garden, reserving part of the ground between the third and fourth roundabouts for “lots for the minor articles of husbandry, and for experimental culture, disposing them into a ferme ornée by interspersing occasionally the attributes of a garden” (view text).[29] According to Therese O’Malley, southern plantations in the United States such as Monticello exemplify the ferme ornée, as endorsed by the English garden designer and writer Stephen Switzer (1682–1745) in his Ichnographia Rustica (1742). Jefferson’s plan for the spring roundabout at Monticello shows how Jefferson integrated farm and garden elements at Monticello. With its use of spiral and serpentine forms, the plan also suggests the influence of Batty Langley’s “irregular” garden designs published in his New Principles of Gardening (1728).[30]

Jefferson continued to play an active role in managing his gardens and farms at Monticello until about 1816, when, at the age of seventy-three, he turned their care over to his grandson Francis Eppes (1801–1888).[31] Jefferson died at Monticello a decade later, on July 4, 1826, and was interred in the cemetery on the site. To pay off Jefferson’s debts, his daughter Martha and grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792–1875) sold most of the contents of the mansion, as well as farm animals, equipment, and 140 enslaved people by public auction in 1827.[32] Smith, who returned to Monticello for a second visit in 1828, remarked on the dilapidated state in which she found the property at that time, noting “Ruin has already commenced its ravages” (view text). In 1831, Jefferson’s heirs sold the Monticello to Dr. James T. Barclay of Charlottesville, who attempted to turn the estate into a silkworm farm. The venture quickly failed, and in 1834 Barclay sold Monticello to U.S. naval officer Uriah Phillips Levy. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased the estate from Levy’s nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, in 1923.

Soon after taking over the estate, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation began to restore it, starting with the mansion and then replanting the groves, vegetable garden, orchards, and vineyards. Information for the restoration was gleaned not only from Jefferson’s detailed plans and notes but also from pioneering landscape archaeological excavations, which began in June 1979 and uncovered the remains of the roundabouts, the ha-ha and paling fence, a complex of buildings along Mulberry Row, and the terraced gardens, vineyards, and orchards.[33] In 1997, archaeologists began a long-term Plantation Archaeological Survey to document and analyze the history of settlement and land-use on the more than 2,000 acres of land that comprised the core of Jefferson’s plantation. Through extensive examinations of the terraced garden wall, the kitchen dependency, and the four corner terraces, the survey has yielded significant insights into how Monticello was constructed and how the surrounding landscape was modified during and after Jefferson’s lifetime. The survey has revealed much about the lives of Monticello’s enslaved inhabitants as well. Between 2000 and 2002, for example, archaeologists uncovered the Park Cemetery, a burial ground for enslaved African-Americans, which was located on the southern flank of Monticello Mountain.[34] The Thomas Jefferson Foundation continues to operate Monticello as a historic site, and archaeological research into the house and grounds is ongoing.

—Lacey Baradel

For more references and direct images, texts and quotes visit the original site here https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Monticello

Site Dates: 1767–present

Site Owner(s): Peter Jefferson August 1707–1757; Thomas Jefferson 1743–1826; Martha Jefferson Randolph 1772–1836; James T. Barclay 1807–1874; Uriah P. Levy 1792–1862; Jefferson Monroe Levy 1852–1924; Thomas Jefferson Foundation 1923

Associated People: Antonio Giannini 1778–1782, gardener; Giovannini da Prato c. 1781–1812, gardener; Robert Bailey 1794–1796, gardener; Wormley Hughes 1781–1858, enslaved gardener; Tom Shackleford, enslaved gardener; George Granger Sr. 1796, enslaved gardener; “Gardener John” 1798–1800, enslaved gardener; Goliah c. 1802, enslaved gardener; Edmund Bacon 1806–1822, overseer; Anne Cary Randolph 1791–1826

Location: Charlottesville, VA · 38° 0′ 30.96″ N, 78° 27′ 19.40″ W

Condition: Extant

Keywords: Aviary/Bird cage/Birdhouse; Basin; Bed; Belvedere/Prospect tower/Observatory; Border; Bower; Bridge; Cascade/Cataract/Waterfall; Chinese manner; Clump; Column/Pillar; Dovecote/Pigeon house; Eminence; English style; Fence; Ferme ornée/Ornamental farm; Gate/Gateway; Greenhouse; Grotto; Grove; Ha-Ha/Sunk fence; Hedge; Kitchen garden; Labyrinth; Lawn; Nursery; Obelisk; Orchard; Park; Piazza; Picturesque; Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden; Pond; Portico; Prospect; Seat; Temple; Terrace/Slope; Thicket; Trellis; View/Vista; Walk; Wall; Wilderness; Wood/Woods

Monticello, located near Charlottesville, Virginia, was the plantation home of the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826). Jefferson designed and redesigned the neoclassical mansion and gardens at Monticello over a period of more than forty years, from approximately 1767 until 1809. Especially notable landscape features include the innovative terraced vegetable garden and vineyards. Today, Monticello is operated as a historic site by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Notes

- ↑ For a transcription of Peter Jefferson’s will, see http://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/1797.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Memorandum Books, 1767, Jefferson Papers, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jefferson relied on either the 1715 or 1742 edition by Giocomo Leoni of Palladio’s text. For a catalogue of Jefferson’s library holdings, see E. Millicent Sowerby, comp., Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 5 vols. (Washington, DC, 1952–59), view on Zotero. See also William Bainter O’Neal, Jefferson’s Fine Arts Library: His Selections for the University of Virginia Together with His Own Architectural Books (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edwin Morris Betts, ed., Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book, 1766–1824 (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1944), 20, view on Zotero; Kevin J. Hayes, The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 119, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William L. Beiswanger, “Thomas Jefferson’s Essay in Architecture,” in Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Foundation; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 2–5, view on Zotero. The north wing—the first part of the house to be habitable—was completed by about 1772, around the time that Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton (1748–1782).

- ↑ Betts 1944, 12, 17, 18, view on Zotero. The first mention of the roundabout is a November 12, 1772, entry in Jefferson’s Garden Book (34). The exact dates of construction for the other three roundabouts is unknown, but Jefferson mentions the second roundabout in a March 30, 1782, entry in his Garden Book (94). The third and fourth roundabouts were completed by the time of his 1809 survey.

- ↑ See also Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 150, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Betts 1944, vii, view on Zotero. Jefferson’s Garden Book is in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

- ↑ Martin 1991, 150–151, view on Zotero; Edwin M. Betts, “Jefferson’s Gardens at Monticello,” Agricultural History 19, no. 3 (July 1945): 182, view on Zotero; Philip J. Pauly, Fruits and Plains: The Horticultural Transformation of America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 24, view on Zotero; Peter J. Hatch, “A Rich Spot of Earth”: Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden at Monticello (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 56, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Letter from Thomas Jefferson, July 29, 1787, from Paris to Nicholas Lewis, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives. During the late 1780s, while serving as minister to France, Jefferson entrusted friends and neighbors, especially Nicholas Lewis (1734–1808), to run Monticello as a tobacco plantation in his absence. Enslaved people living at Monticello not only maintained Jefferson’s gardens but also established their own vegetable gardens on the property and sold extra produce to the Jefferson family. Hatch 2012, 63, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Beiswanger 2002, 5, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Adams was then serving as minister to the Court of St. James. Martin 1991, 145, view on Zotero; Hatch 2012, 20, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Betts 1944, 111–12, view on Zotero. The memorandum, “A Tour to Some of the Gardens of England,” is reproduced on pages 111–14.

- ↑ Hatch 2012, 22, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lucia Stanton, “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 72–73, 63, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Bailey left Monticello in 1797 to start his own commercial nursery in Washington, DC. Hatch 2012, 23, 25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lord Kames discussed the walkways in his in his essay “Gardening and Architecture.” Beiswanger 2012, 5, 9, 23, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William M. Kelso, “Jefferson’s Garden: Landscape Archaeology at Monticello,” Archaeology 35, no. 4 (July/August 1982): 38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Beiswanger 2012, 18, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martin 1991, 153–154, view on Zotero; William L. Kelso, “Landscape Archaeology and Garden History Research: Success and Promise at Bacon’s Castle, Monticello, and Poplar Forest, Virginia,” in Garden History: Issues, Approaches, Methods, ed. John Dixon Hunt (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1992), 36, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jefferson paid Lewis Dangerfield, a farmer from Fredericksburg, for the use of Dangerfield’s enslaved workers. Hatch 2012, 5, 25, 30, 59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hatch 2012, 3–4, 47, view on Zotero. Jefferson kept some of the seeds from the Lewis and Clark expedition to grow at Monticello, but he sent most to William Hamilton and Bernard M’Mahon in Philadelphia. Jefferson also received annual shipments of seeds from André Thöuin, director of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, between 1808 and 1822. In 1809, shortly before leaving Washington, DC, to retire to Monticello, Jefferson purchased at least thirty new vegetable varieties for his garden from seedsman Theophilus Holt. See pages 19–20, 27, 33.

- ↑ Hatch 2012, 7–8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hatch 2012, 27, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kelso 1982, 39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter J. Hatch, “The Gardens of Monticello,” in Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville, VA: Thomas Jefferson Foundation; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 141, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stanton 2012, 190–91, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Hatch 2002, 125, 129, 130, view on Zotero. According to Hatch, twenty-five percent of the flowers documented at Monticello were native to North America.

- ↑ See also Martin 1991, 148, 161, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Appropriation and Adaptation: Early Gardening Literature in America,” Huntington Library Quarterly 55, no. 3 (Summer 1992): 409, 412–13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martin 1991, 163, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Stanton 2012, 69–70, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kelso 1982, 38, view on Zotero; Kelso 1992, 37–53, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For documents related to past and current archaeological projects at Monticello, see https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/current-research.

- ↑ Jump up to:35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Betts 1944, view on Zotero.

- ↑ François Jean Chastellux, Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781, and 1782, 2 vols. (London: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1787),view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Maria Cosway, October 12, 1786, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-10-02-0309. Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10, June 22–December 31, 1786, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954, 443–550).

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Angelica Schuyler Church, November 27, 1793, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Isaac Weld Jr., Travels through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (London: John Stockdale, 1799), i, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Mann Page, May 16, 1796, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), view on Zotero

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to William Hamilton, July 31, 1806, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Anne Cary Randolph, June 7, 1807, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Edmund Bacon, November 24, 1807, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Anne Cary Randolph, February 16, 1808, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Anne Cary Randolph, March 22, 1808, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Jump up to:47.0 47.1 Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. by Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Henry Latrobe, October 10, 1809, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, June 6, 1814, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Martin 1991, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, rev. ed. (London: Longman et al., 1850), view on Zotero.

Media Attribution

- “View of the West Front of Monticello and Garden” by Jane Pitfield Peticolas is in the public domain.

- Screenshot of “Monticello Virtual Tour” is used under fair dealing.

- Various plans of Monticello by Thomas Jefferson are in the public domain.