Dada – Deborah Gustlin & Zoe Gustlin Gustlin, Deborah, and Zoe Gustlin. Dada (1916-1924). Evergreen Valley College, 28 Mar. 2022, https://human.libretexts.org/@go/page/121531.

Dada materialized from the chaos of World War I, a conflict employing trench warfare and advanced weaponry, killing millions of people. Artists and poets of the period believed war degraded social constructs and values, established corruption, conformity, and violence. A war is dependent on the ability and efficiency of machines instead of the human body, a battle without humanity. “The beginnings of Dada,” poet Tristan Tzara recalled, “were not the beginnings of art, but disgust.”[1] The name Dada was formed by Richard Huelsenbeck and writer Hugo Ball when they looked at a French-German dictionary and noted Dada was ‘rocking horse’ in French or foolish naivete in German, the right word for an irrational movement. Dada’s ideas grew from a small group of artists in Europe who wanted to create new forms of art and alternatives to the existing methods and standards. They tried to criticize life, governments, capitalism, and institutions they found around them through their art; the aesthetics of their work was not the focus. Leah Dickerson wrote,

“For many intellectuals, World War I produced a collapse of confidence in the rhetoric—if not the principles—of the culture of rationality that had prevailed in Europe since the Enlightenment.”[2]

They experimented with the idea of art, used multiple types of materials, and innovated with readymade resources, collage techniques, and photomontages. The artists started improvising with elements to make the assemblages, criticizing the general world purview and the distortions of those in power. They used old photos, newspapers, books, or letters cut apart into abstract forms and reassembled, governmental and political propaganda destroyed and reworked as new words. Readymade objects were constructed in parts to define a concept or idea. Painter Albert Gleizes remarked, “Never has a group gone to such lengths to reach the public and bring it nothing.”[3] Dadaism dehumanized art with pointless materials and images reshaped randomly outside of any convention. They heavily influenced modern, conceptual, performance, abstract art, and installation art for a movement lasting less than ten years.

Dada started in Zurich, Switzerland, followed by Berlin, New York City, and Paris. The artists lived and worked in more than one place, especially those disrupted by World War I. Switzerland was a neutral country, and many temporarily stayed there during the war or to escape the draft. Most artists worked in other styles and movements after Dadaism, Surrealism a natural subsequent movement many of them pursued other styles. Artists in this section include:

Francis Picabia

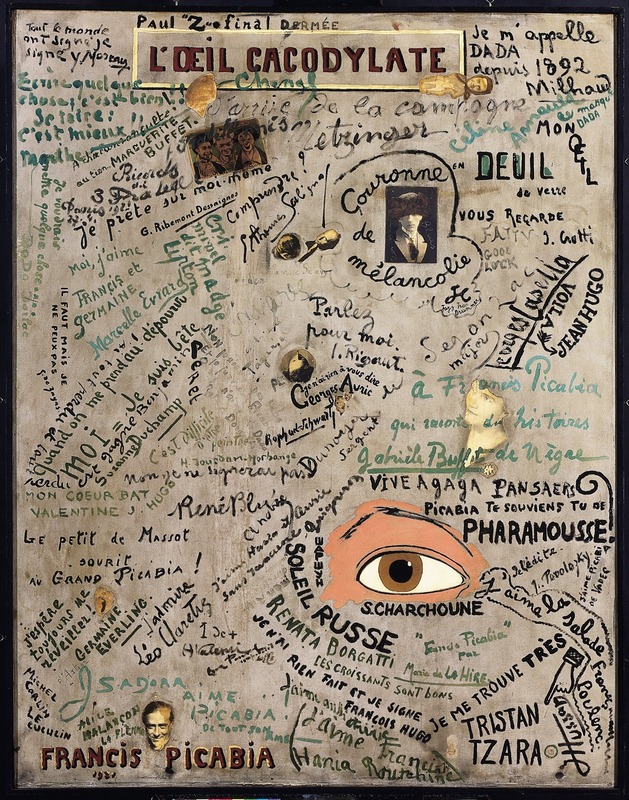

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) was born in Paris when his father was the Cuban attaché in Paris. His mother died at an early age, leaving Picabia a large inheritance and freeing him to study at different academies in France. Originally his work was similar to the Impressionists; then, he adopted Cubism. During World War I, he moved between New York and Switzerland, painting and publishing the journal 391, adding experimental ideas. From 1912 until 1921, he worked with the abstract ideas of Dadaism. He became friends with Marcel Duchamp, and Alfred Stieglitz had his show at Gallery 291. Picabia was fascinated with the shape and form of different objects, synthetically creating art based on mechanical processes. Alarm Clock (5.7.1) was made by applying ink directly on the mechanism of a clock to print on the paper, joining the gears with lines. He used large block letters for the cover of the Dada magazine issue number 4-5. Picabia viewed the work as logic disintegrating in the ongoing onslaught of the war yet portraying the clock as neutral Switzerland. L’Oeil Cacodylate (Cacodylic Eye) (5.7.2) displays the large block letters at the top of the image; a sizeable brown eye is near the bottom. The legend about the painting started when Picabia had an eye infection, and the doctor gave him Cacodylate de Sodium, a medicine used in that era. When his friends visited, he asked them to inscribe an image or words on his working canvas. The canvas was covered with signatures, messages, and collaged photographs, becoming a group art project. At this period, lettering on modern European artwork was minimal; this work was revolutionary.

%252C_Dada_4-5%252C_Number_5%252C_15_May_1919.jpg?revision=1)

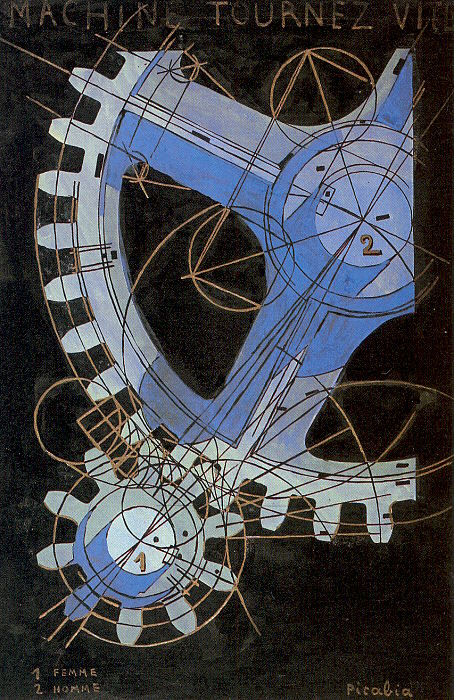

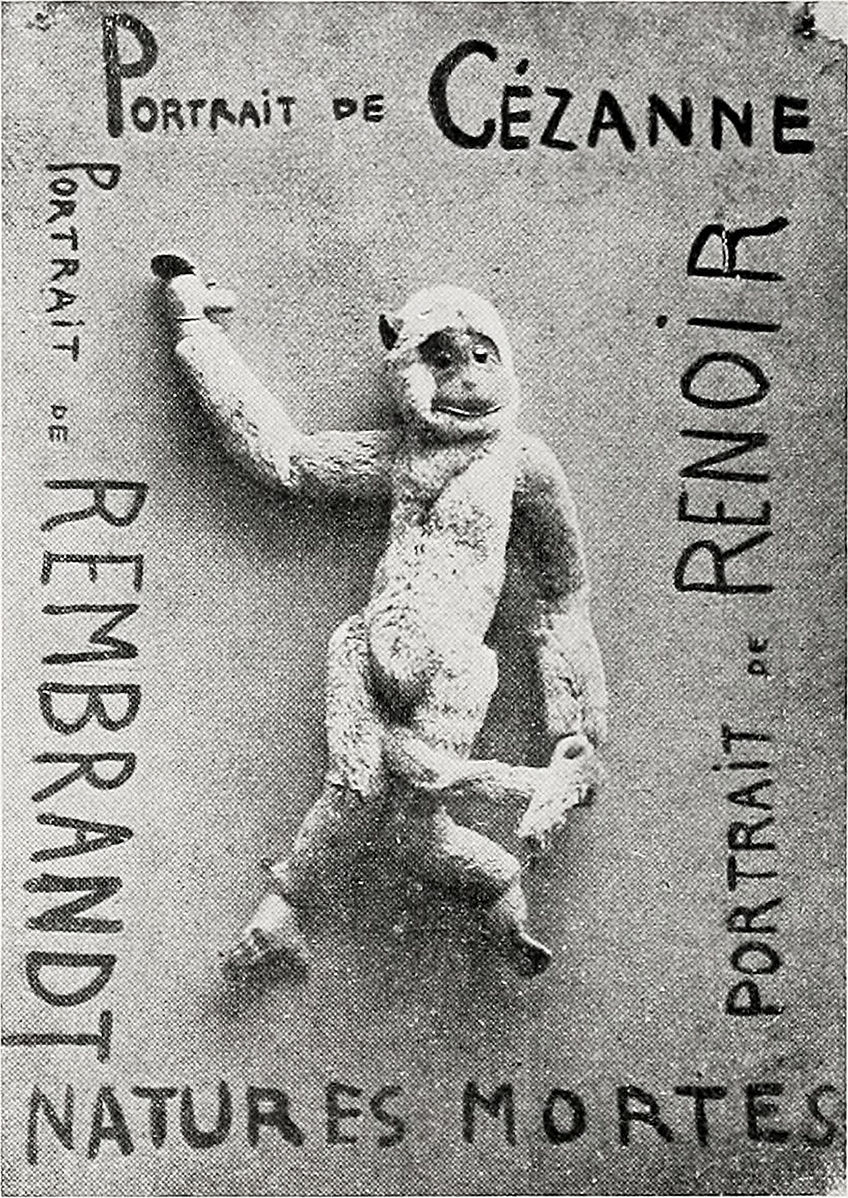

Machine Turn Quickly (5.7.3) is an example of Picabia’s mechanomorphic works. The Dadaists were horrified by the senseless violence of World War I and the destruction of the concept of humanity. The growth of science and technology in the industrial age added to the dehumanization of people. People became machines in disguise. Picabia incorporated these feelings into his artwork using mechanical representations of gears, wheels, pulleys, or other parts of mechanized works. He used lines so finely marked they appear to be machine-produced. Natures Mortes; Portrait de Cézanne, Portrait de Renoir, Portrait de Rembrandt(5.7.4) is a characteristic example of Dada anti-art. It is offensive and declares painting dead. The readymade monkey is the center of the work, punctuation in the middle of the determining idea. Picabia used rudimentary lettering around the tattered monkey, enhancing the concept of the named artists as no more than stuffed monkeys.

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was born in France; his grandfather was a well-known painter, and the Duchamp household was filled with cultural activities. Some of his siblings also became successful artists. He studied at an academy for a while before he was drafted into the infantry in 1905. Through his brothers, he became acquainted with the Cubist artists and started painting in the style. When he was turned down at one of the Cubist exhibitions for his painting Nudes Descending a Staircase, the painting was displayed in New York and caused a fury. He moved away from the association with a group. In 1913, he painted his last Cubist-based image, moving away from the painterly look and turning his interests to a more technical and exhibitory concept. He was exempt from the draft because of a heart murmur during the war, and he wanted to leave Paris. His painting in New York may have caused an uproar, but it also helped sell his other paintings and added to his reputation. Duchamp was a longtime friend of Francis Picabia who was connected with the Zurich Dada, and when he came to New York, Duchamp, Picabia, and Man Ray met continually. They traveled back and forth between Europe and New York. Dada in New York was not as serious as in Europe, and Duchamp’s first significant contribution was the Fountain, generating another uproar. “Readymades” became his theme. He used found objects and assembled them into something, questioning the whole concept of art and its glorification. Duchamp considered paint a readymade product, no different than other things.

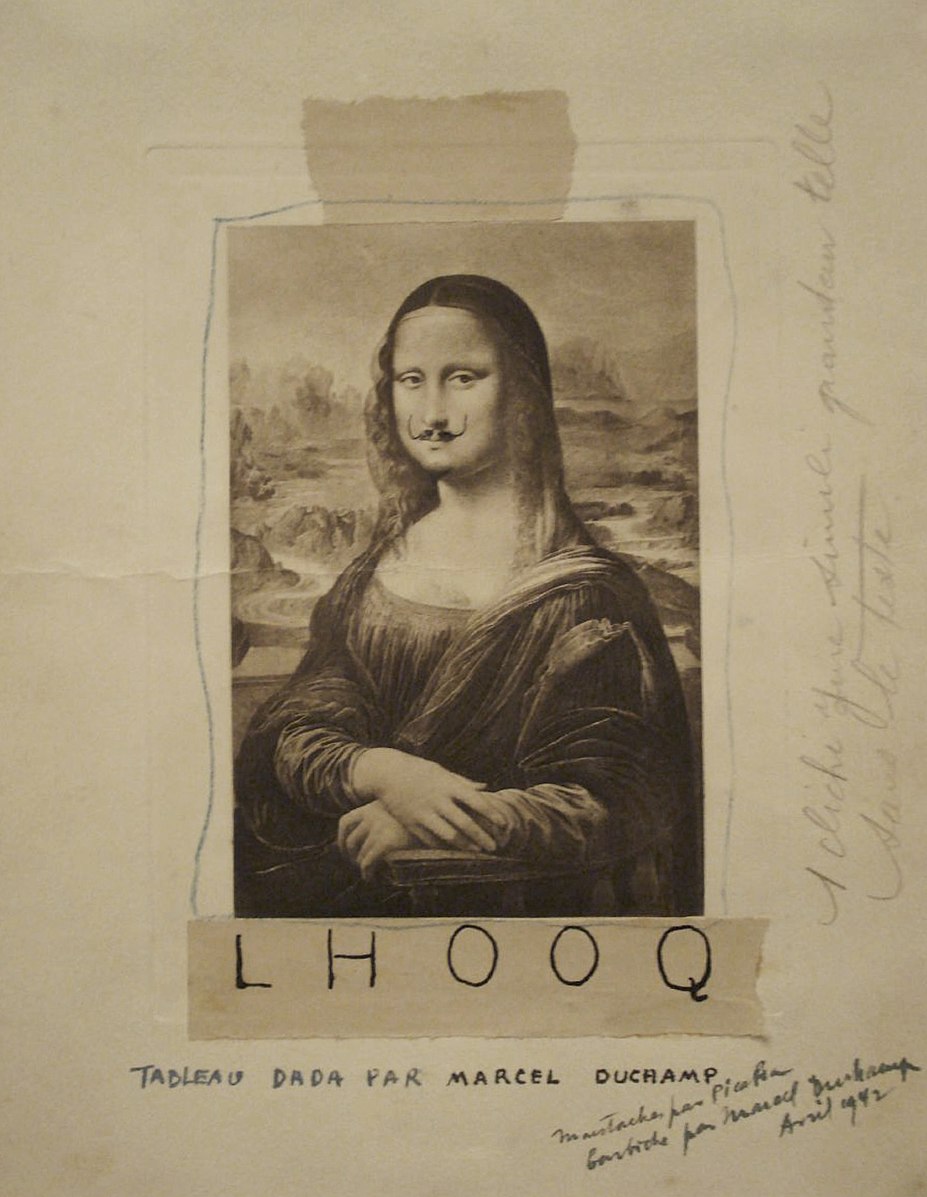

Duchamp used a readymade postcard of the Mona Lisa for L.H.O.O.Q.(5.7.5), drawing a moustache. He resided with Picabia when he made the image, one of his methods to upend cultural and rational artistic values. Duchamp liked to play with words, and the letters L.H.O.O.Q. in French sound as “Elle a chaud au cul” (There is fire down below). Duchamp had a female pseudonym, and perhaps he added the gender reversal mustache to masculinize the female image. The image was successfully mass reproduced and a symbol for Dada. The Fountain (5.7.6) was submitted to an exhibition by the Society of Independent Artists and turned down, not considered art and creating the question of “what is art.” The work was considered art by some because the Readymade object was completely divorced from its original place and intent, reassigned a new name, further removing it from its normal position also adding his signature. The publicity made the Fountainnotorious and challenged the idea of how institutions defined and chose art. “In 1913, I had the happy idea to fasten a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and watch it turn,” he later wrote, describing the construction he called Bicycle Wheel, a precursor of both kinetic and conceptual art.[4] Bicycle Wheel (5.7.7) was assembled from readymade objects, repositioned, signed by Duchamp, and considered art. Although he liked to use readymades, he did not consider them as unique objects. After he assembled the wheel on a stool, he found it comforting to watch the wheel turn, looking through it as though watching waves form or flames dance.