1.2 Academic Art & Arts Education

Baroque artist, designer, and court-appointed decorator Charles Le Brun, designed or supervised the production of most of the paintings, sculptures, decorative objects, and interiors commissioned by French royalty. Trained as a painter, Le Brun was the founder of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1648. “Known today as The French Academy of Fine Arts (Academie des Beaux-Arts), It was abolished temporarily during the French Revolution before being renamed the Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Academie de Peinture et de Sculpture). In 1816, it was amalgamated with two other arts bodies, the Academy of Music (founded in 1669) and the Academy of Architecture (founded in 1671), to form the Academie des Beaux-Arts.” [1]

The academy controlled all aspects of artistic endeavors, and it was extremely difficult for artists and designers working outside of the academy to make a living. Acting as a center for arts education and display, members of the Academy received technical instruction in painting and sculpture, as well as were awarded possibilities of exhibition. Monopolizing the world of art and commerce, the academy was created to ensure creative standards were approved and upheld by the government and the King of France. In order to bring his skills to the attention of potential customers, an artist had to exhibit his works in public, and the only permitted public art show was the Salon, he could only exhibit if his submission was “accepted” by the Salon jury.

Accepted Academicians (members of the academy), were not only responsible for the training of the future artists and designers of France, but they were also under the obligation to the King in deciding the aesthetic qualities of French interior and exterior environments. Being delegated as the sole participants in the Salon, an annual exhibition for the members of the academy held in the Louvre left the academicians eligible for official arts jobs. Accordingly, “Art created, shown, and accepted by the members of the Academy is now called Academic Art, and all artistic practice was categorized under a hierarchical schematic. As part of its regulation of French painting, the French Academy imposed what was known as the hierarchy of genres, in which the five different painting genres were ranked according to their edification value. This hierarchy was announced in 1669 by Andre Felibien, Secretary to the French Academy, and ranked paintings as follows: (1) History Painting; (2) Portrait art; (3) Genre Painting; (4) Landscape Art; (5) Still Life Painting” [2]

The majority of the lower classification of painters such as still life painters were women. This system was used by the academies as the basis for awarding scholarships and prizes, and for allocating spaces in the Salon,[3] leaving women artists outside of the commercial and public art world.

The academy also regulated how a painting should be painted, the types of colours an artist could use, the overall style, and even how much of the brushwork should be visible. Some of the most important artworks were not accepted into the academy because of the strict system of rules they had in place, and women were seldom invited at all. Women were excluded from essential training courses, such as anatomy and life drawing classes where it was practically illegal for a woman to participate in, yet because these courses were the essential teachings for History style of painting, women were excluded from the academy.[4]

The power of the monarchy over cultural production was an extreme propagandistic enterprise, as we saw with the creation of the Royal Academy, and also it affected the production of textiles and other designed objects. The court was the cultural center of Europe and this was due to the supreme rule of the king through his absolute political power. The king wanted to control everything and that included how objects were designed, manufactured, and who was allowed to own them. Charles Le Brun was made the director of the Royal Factory of Furniture to the Crown at the Gobelins Manufactory, and he was responsible for overseeing all production. LeBrun, “Orchestrated numerous craftsmen, including tapestry weavers, painters, bronze-workers, furniture-makers, and gold- and silversmiths, who supplied objects exclusively for the king’s palaces or as royal gifts.”[5] As a result of financial difficulties, the factory was forced to close in 1694, reopening in 1699 but only to produce tapestries.[6]

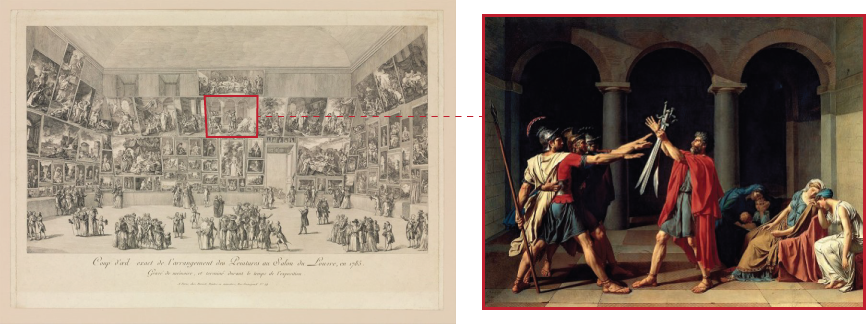

Due to the stronghold and power of the French academy, it was very difficult for artists and designers to make a living if they were working outside of the hierarchal categorizations of representation. Remember there were five categories of paintings that were deemed acceptable to make and these were (1) History Painting; (2) Portrait art; (3) Genre Painting; (4) Landscape Art; (5) Still Life Painting. Exhibitions of work by the Royal Academy of Painters and Sculptors were held here from the late seventeenth century and the word Salon now held a more specific meaning when it came to the display of art & design objects. Today we know this as the Salon Hang, where multiple images are grouped together on a wall. The salon hang became the established pattern at the annual Paris Salon, and its hierarchy of genre was visualized. Works depicting history painting were hung at just above eye level on the wall, while those of the other categories were hung higher or lower than eye level. (see image below) Over the years, artists and designers would conduct exhibitions and events in resistance to the Salon of the Academy, in an attempt to overthrow the rule the court had on the production of art and design objects. The most notable of these artists are Gustave Courbet and the Impressionists of the nineteenth century.

(1) History Painting; (2) Portrait art; (3) Genre Painting; (4) Landscape Art; (5) Still Life Painting. Right: Jaques Louis David Oath of the Horatii, 1784

Throughout the history of the western world, meaning the earth and all of its components, natural or manmade — people have always had a sense of exploration, and an innate curiosity about situated and lived-in environments. Think now about how you understand the phrase we encountered last year, the Grand Tour?

Beginning in the 16th century, The Grand Tour was a specific educational experience pursued by wealthy young men. By the period of the enlightenment, it was almost an essential and expected aspect to the pursuit of knowledge. I believe it stemmed from two ideas or practices, the practice of pilgrimage and the cultural creation of affording leisure time to wealthy people.

Pilgrimage is a religious practice, predominately engaged by believers of either Christianity or Islam, where they partake in walking great distances to visit their respected religious monuments. Jean Sorabella, writing for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, describes The Grand Tourist as being typically a young man with a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature, meaning ancient Greek and Ancient Roman literature,[7] which I remind you was only rediscovered and intensely studied during the period of the renaissance. These wealthy men were offered the ability to practice what is known as a leisurely lifestyle, they had the privilege of leisure time. They were how contemporary theorists described as being from a leisure class, they had the financial means to travel, and a cultural interest in fine art practices, primarily influenced by a specific education. Many would begin their journeys in London England, and then visit all of the main cities of Europe with the goal to learn as much as they could about architecture, art, design, and cultural differences from their own lived experiences. Italy was an important stop on the Grand Tour, and specific lessons on ancient Rome, the renaissance, and the Italian baroque were sought after.[8] The art market also benefitted from the Grand Tour, because the tourists were expected to bring home souvenirs, to demonstrate their knowledge of the areas they visited. The Grand Tour gave concrete form to northern Europeans’ ideas about the Greco-Roman world and helped to foster Neoclassical ideals. Secondly, the grand tour was used to facilitate the guilds and to educate their members, the equivalent to the idea of the journeyman role in the numerous guilds of Western European Cities.

Think back to what the role of the journeyman entailed? And more specifically what is considered a guild?

Read: Félix Duban and the Buildings of the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts, 1832-1840

van Zanten, David. “Félix Duban and the Buildings of the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts, 1832-1840.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 37, no. 3, [Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press], 1978, pp. 161–74, https://doi.org/10.2307/989207.

Media Attributions

- “Self Portrait”, by Charles le Brun is in the public domain.

- “Oath of the Horatii” by Jacques-Louis David is in the public domain.

- “Untitled” by unknown with unknown licence.

- “La Cour du Palais des études de l’École des beaux-arts” by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.

- “The Entrance to the Grand Canal” by Canaletto is in the public domain.

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/lebrun.htm ↵

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/lebrun.htm ↵

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/lebrun.htm ↵

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/old-masters/lebrun.htm ↵

- https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/group/103KBP ↵

- https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/charles-brun ↵

- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm ↵

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/grand-tour.htm ↵