7.5 The Gay Rights Movement

A Precursor to Queer Designers:

Smarthistory – Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (billboard of an empty bed) by DR. TOM FOLLAND

Yet Gonzalez-Torres didn’t merely reference the work of earlier Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Dan Flavin—he introduced a specifically contemporary note into his work. In the late 1980s and early 1990s artists were asking new questions around the construction of identity—including gay identity. For instance, the lights in his work were redolent of the environment of a dance club (left), and the candy on the floor was a perverse reference to the drug AZT used to combat HIV. And the bed? Much like the paired wall clocks he created the same year entitled Perfect Lovers that marched slightly out of step with one another (one is a few seconds off), the censored image of same-sex love slowly makes its imprint.

Bed’s sexual politics

By 1987, a new era of gay activism had begun. The Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACTUP) formed and suddenly old questions around the relationship between art and politics took on new significance for gay artists. Artist-collectives like Gran Fury used appropriated image and text to convey overt political messages around the politics of AIDS. But Gonzalez-Torres did not follow this route. His disappearing but perpetually replenished works (viewers were allowed to remove a poster or take a piece of candy) took a more elegiac path: it was one in which any direct representation of homosexuality was seldom apparent. Thus his art became an abstract memorialization of loss. Gonzalez-Torres’ memorialization resonated especially during a time when Ronald Reagan (U.S. President from 1981 until 1989) notoriously never uttered the word “AIDS” because of its predominant association with homosexuality. Heads pressed onto pillows in the Untitled billboard thus becomes a simultaneous declaration and disavowal of same-sex love—writ large within an urban landscape.

As an artist, Gonzalez-Torres came of age during the 1980s (he was born in 1957 in Cuba). At that time, Postmodern artists often worked with existing imagery and text, appropriating and examining an increasingly media-saturated world. His earliest work was in that vein. In the manner of Jenny Holzer, who reproduced found slogans or random sentiments on wheat-pasted posters throughout the streets of lower Manhattan in the late 1970s, one of Gonzalez-Torres’ earliest works is a framed photostat (an early version of a photocopy) from 1988 of a sentence. It’s really a jumble of words—white letters on a black background that read “supreme 1986 court crash stock market crash 1929 sodomy stock market crash supreme 1987.” In this way, he offered a poetic commentary on the erasure of gay history by sandwiching a reference to the 1986 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the state of Georgia’s sodomy laws (which effectively criminalized homosexuality) between significant dates in economic history.1

Back to the future

Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) marked an important threshold in contemporary art history. In the late 1980s the art world underwent significant changes. It seemed to many critics at the time that postmodern art existed only to illustrate complex philosophical concepts, while the felt aspects of experience, important for the renewed surge of identity politics (political alliances based on identity, like the women’s movement), were ignored. Foregrounding the bodily dimension of experience, artists like Robert Gober, Kiki Smith and Jane Alexander created sculptural works with visceral impact. Artists began to return to discarded artistic strategies like narrative, constructed (rather than appropriated) forms—anything that would invoke a sense of the contemporary, lived aspect of everyday experience without mediation. Bodies were often splayed upon the gallery floor or its parts protruded from a wall.

Gonzalez-Torres’ art had, in a sense, a foot in both camps: Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) bore resemblance to the billboards Barbara Kruger had done as early as 1985. Her Surveillance is Your Busy Work is one that was unveiled in Minneapolis that year and featured her trademark use of advertising imagery reconfigured with text to correspond to discussions around public space, gender and corporate culture. But Gonzalez-Torres’s image of a disheveled bed was shorn of any textual or even didactic directive. Significantly, the image is of his own bed. Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) suggested—even if it did not portray—a tangible if disappearing presence.

1. This ruling was eventually overturned.

Additional resources:

Print/Out: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, on Inside/Out, MoMA’s blog (April 4, 2012)

Biography of the artist from Oxford University Press on MoMA.org

The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Art and Photography: the 1980s on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

GENERAL IDEA

General Idea – Art Addressing Queer Identity and the AIDS Crisis – from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/canadarthistories/part/activism/

Another art group that coalesced in Toronto in the period was General Idea, initially an anonymous group that crystallized into an intentional three-part group comprised of Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson. The group is well known for their work addressing the discourse on AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, as explained by Sarah E.K. Smith:

In the late 1980s AIDS was a taboo topic and a climate of fear surrounded the disease due to widespread and extreme homophobia. This was because initially the disease was thought to exclusively affect gay men. For instance, in 1981 the first article in the New York Times to address AIDS identified it as a cancer that only affected homosexuals.62 This was not helped by the fact that inaccurate and inflammatory information about the disease circulated widely in the media.63 Many aspects of the AIDS pandemic, including its scope and severity, were not at first understood. Tremendous prejudice—including within the medical community—was widespread given the initial impact of AIDS in the gay community and its sexual transmission. As such, there was a moral dimension to the AIDS pandemic that activists, as well as artists, sought to address.64 (Source: https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/general-idea/biography/)

Within this context, General Idea took a brazen approach to addressing the crisis, beginning with the 1987 painting AIDS produced for a fundraiser to benefit the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). This painting subsequently sparked the group to more broadly address the discourse on HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In AIDS, 1987, the artists appropriated American artist Robert Indiana’s (b. 1928) painting LOVE, 1966, replacing the word “LOVE” with the name of the new disease. The ironic appropriation of Indiana’s work was, AA Bronson later noted, in “bad taste. There was no doubt about that.” At the time, other artists were addressing the disease didactically in their work, in contrast to the more ambiguous statement General Idea made with AIDS.

Despite the initial reaction to the work, General Idea went on to create a series of projects around their AIDS logo, producing these in diverse media, from posters to stamps to rings. They advanced this logo to raise awareness about and combat the stigma and misinformation surrounding AIDS. Bronson stated, “Part of the hook of it for us was the fact that it involved so many issues, not only health issues, which were especially acute in the U.S., but also issues of copyright and consumerism.” The artists also continued to raise funds for AIDS charities through initiatives such as General Idea’s Putti, 1993, a large-scale installation created from a commercially available seal pup–shaped hand soap placed on a beer coaster. Ten thousand of the soaps were assembled to create a gallery installation and were available for viewers to take, with the suggestion to leave a $10 donation for a local AIDS charity.

The significance of General Idea’s activism cannot be understated. At the time AIDS was a taboo topic surrounded by fear. Speaking to the climate of the era, artist and writer John Miller explained, “In 1987 especially, identifying oneself as HIV-positive differed from coming out. You could lose your job and your friends. Others still might want to quarantine you. Even obituaries skirted all mention of the disease.”

In the late 1980s General Idea’s AIDS work took on personal significance. One of the group’s closest friends (who helped in producing Going thru the Motions, 1975–76, and Test Tube, 1979) died of AIDS-related causes in 1987 in New York. The group served as primary caretakers for the last weeks of their friend’s life. Partz and Zontal were diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1989 and 1990, respectively. Both artists publicly disclosed their status and, until their deaths in 1994, General Idea continued to create poignant and engaging artwork addressing AIDS. (Smith 2016, ACI).

In 1994, General Idea’s collaboration concluded with the deaths of Zontal and Partz from AIDS-related causes. Bronson continued to produce work and in the wake of the loss of Zontal and Partz and produced works in tribute to General Idea.

LGBT Rights and the AIDS Crisis https://boisestate.pressbooks.pub/arthistory/chapter/modern-to-postmodern/

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s led to increasing stigma against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, who in turn protested with political art and activism.

The LGBT community responded to the AIDS crisis by organizing, engaging in direct actions, staging protests, and creating political art. Some of the earliest attempts to bring attention to the new disease were staged by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a protest and street performance organization that uses drag and religious imagery to call attention to sexual intolerance and satirize issues of gender and morality. At the group’s inception in 1979, a small group of gay men in San Francisco began wearing the attire of nuns in visible situations, using high camp to draw attention to social conflicts and problems in the Castro District.

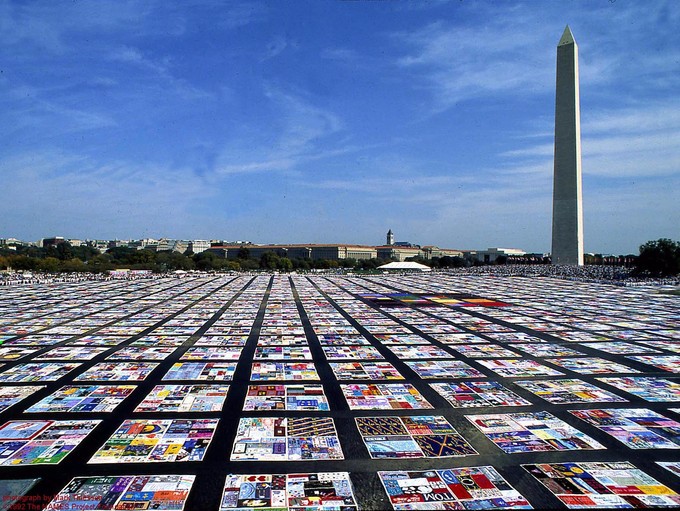

One of their most enduring projects of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence is the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, in which members who have died (referred to as “Nuns of the Above”) are immortalized. Created in the early 1990s, the quilt has frequently been flown around the United States for local displays.

A number of young artists who themselves were victims of AIDS made art that brought attention to the issue. Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz and Robert Mapplethorpe were artists who succumbed to the disease but created lasting work that brought attention to an issue that was for too long ignored by the politicians given the populations most affected by it at that time, and also especially in the case of Mapplethorpe – creating a Foundation for the arts and ongoing research into the disease.

For further study:

Vider, Stephen. The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226808222