2.3 Realism

Please Read

Gustave Courbet, “A Burial at Ornans” – Jennifer Lorraine Fraser

“The title of Realist was thrust upon me just as the title of Romantic was imposed upon the men of 1830. Titles have never given a true idea of things: if it were otherwise, the works would be unnecessary. Without expanding on the greater or lesser accuracy of a name which nobody, I should hope, can really be expected to understand, I will limit myself to a few words of elucidation in order to cut short the misunderstandings. I have studied the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns, avoiding any preconceived system and without prejudice. I no longer wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of “art for art’s sake”. No! I simply wanted to draw forth, from a complete acquaintance with tradition, the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality. To know in order to do, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal.” Gustave Courbet; Realism 1855

Gustave Courbet (1819 – 1877), is noted to be one of the most influential artists of modern Western culture. Somewhat unwillingly, Courbet is considered a leading figure of the French revolution of 1848, and also the founder of the artistic movement that arose from the political upheaval in France, Realism. Courbet artfully created his own persona, to pursue greater artistic achievement and to gain recognition. This essay will be an exploration of Courbet’s monumental painting A Burial at Ornans (fig.1). With a focus on its key subject matter, its style, and a sliver of the social/ historical significance of its time, I will discuss why its relevance today is as important as it was in the 1850s.

The original title, A Painting of Human Figures, the History of a Burial at Ornans, ascribes the subject matter in its entirety. In 1848, Courbet returned to his hometown of Ornans to attend the funeral of his maternal grandfather, Oudot Jean Antoine. The funeral was conducted in a new cemetery in the farming community of Ornans, and it is said, the following year, Courbet used this dramatic event to create the painting, however, it is not confirmed this particular funeral is at the core of the painting. Some experts have suggested the left-hand side of the frieze-like composition holds a portrait of Courbet’s deceased grandfather, being very much alive in the crowd, hence the reason for questioning whether or not it is indeed the funeral of M. Antoine. Courbet’s grandfather was a veteran of the 1799 French revolution and there are two other veterans represented in the foreground of the painting. The background is represented by Courbet’s depiction of the landscape of Ornans. To the viewer, there is an allusion to being present in the cemetery and attending the funeral alongside the many townspeople, of being immersed in the composition as one of the different classes of people represented. Within the anti-hierarchical composition, there are portraits of known townspeople, the local priest and bishops, as well as Courbet’s beloved sisters.

Gustave Courbet did not only want to be considered an artist but also to be recognized as an influential man; a man of his times. A Burial at Ornans was one in a series of paintings Courbet created in his newly formed stylistic vision. Many scholars believe Courbet was the founder of French Realism, and the philosophy of art at the centre of Courbet’s vision is the notion of the artist being true to oneself and of creating art in everyday occurrences of life, not only when creating an actual art piece. To be an artist is to always be living with a sense of purpose, to expose the events in their own lives in the most real and honest form. This sense of purpose extends to future generations with whom Courbet shares the truth of his philosophy of a ‘living art.’ “Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the presentation of real and existing things.”[1]

Realism follows romanticism on the timeline of Western art history, and in it, we see a higher emphasis on the commercialism of visual art as well as a new intellectual debate upon the role of art-making itself. For centuries paintings consisted of renderings of beautiful and ornate biblical stories, monumental in form and size. During the romanticism period, artists created paintings emphasizing historical events combining a portrayal of idealized moral stories at their essence. Courbet differs from the romantics by inserting everyday themes into the subject matter, the stronger sense of naturalism, is accentuated by the darkness of his canvases. A Burial at Ornans is huge, a full ten by twenty-two feet and the figures in the foreground are life-size and larger. The two veterans on our right center are close to seven feet tall. That dimension was usually reserved for paintings depicting historical and biblical stories. Every aspect of the painting was created to attempt to portray the truth, even within the darker palette he used showing the true nature of light. There are no illuminated figures, only diffused lighting upon certain individual characteristics of each figure represented.

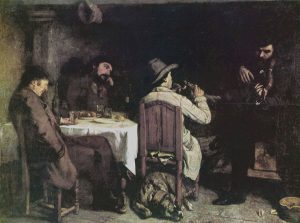

After many refusals, in 1849, Courbet’s work After Dinner at Ornans (Fig.2) won the gold medal at the Paris Salon. This accolade from his peers enabled Courbet to enter as many paintings as he wished in the subsequent years without fear of rejection. “A Burial at Ornans”, among others, was on show in the Paris salon of 1851. By 1855 the International Exhibition went to Paris and Gustave was invited to present his work; three entries were dismissed, “A Burial at Ornans” being one of them. As a result of this rejection Courbet decided to stage his own exhibition of his work directly across the street from the International Exhibition. The subject of his exhibition was entitled Realism, and he copied the practice of the political figures of the day by presenting a manifesto of his intent. (Please see title page) A manifesto reclaiming realism as his own by emphasizing that titles are given when they shouldn’t be or when they mean something else, just so that the critics and connoisseurs of art, and political theory can engage one another in trivial pursuits.

Gustave Courbet was influenced by the past and by new inventions of the present. He would find copies of paintings that hung in the Louvre and paint over them, copying the masters who preceded him. He was influenced by the secular art of the Netherlands and the darker Spanish masterpieces. One of the most important influences for Gustave Courbet was the invention of photography which allowed for artists to interpret a whole new way of perceiving their worlds. Photography contributed to an emphasis on what was current and most importantly to what was real.

Gustave Courbet blazed the trail for how we view the art of art-making today. With his strong sense of character and knowledge of the art market, Courbet set the stage for how contemporary artists are perceived in present society. Similar to philosophers and educators of the past artists today are seen as elevated cultural beacons of truth. Present-day artists, with their individual style and convictions, have more freedom of thought and style than ever before. It is safe to say that if Gustave Courbet had not been set on creating a niche for himself, the history of modern art would be very different for everyone. Without Gustave Courbet, the history of art would have been completely changed. His manifesto and his way of life highly influenced the impressionists of the early 1900s. We do not know if Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, and others would have ventured out on their own, after their own rejections by the Paris Salons of their time if it was not for the strength of artistic endeavor portrayed by Gustave Courbet.

“I honor myself by remaining faithful to my lifelong principles; if I betray them, I should desert honor to wear its mark.”

Gustave Courbet died in exile in Switzerland. He was 58.

His remains were moved to the very same cemetery at Ornans in 1919.

Honour, Hugh, and John Fleming. The Visual Arts: a History. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2010. Print.

Piper, David, and Philip S. Rawson. “French Realism.” The Illustrated History of Art. London: Bounty, 2005. Print.

Piper, David, and Philip S. Rawson. “Courbet: The Artists Studio.” The Illustrated History of Art. London: Bounty, 2005. Print.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. “Chapter 2, Pg 100-101.” Beauty and Art, 1750-2000. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

The Great Artists, Romantics and Realists, Courbet. Kultur International Films, LTD. DVD., 50minutes

The Structure of Beholding in Courbet’s “Burial at Ornans” Michael Fried, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Jun., 1983), pp. 635-683, Published by: The University of Chicago Press Found online jstor.org

Larger than Life, Arts & Culture, Smithsonian Magazine.” History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places Smithsonian Magazine. Web. 11 July 2010. <http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/larger-than-life.html>.

“Musée D’Orsay: Gustave Courbet A Burial at Ornans.” Musée D’Orsay: Accueil. Web. 11July2010; http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/search/commentaire/commentaire_id/un-enterrement-a-ornans-130.html?no_cache=1>.

Undergraduate paper: Gustave Courbet, “A Burial at Ornans”

Jennifer Lorraine Fraser 2010 – Edited 2022

For Further Study: (not assigned)

https://openeducationalberta.ca/19thcenturyart/chapter/chapter-6/#footnote-251-31

ROSA BONHEUR

The new woman is a concept that began in the 1890s and moved into the 20th century, a turn-of-the-century phenomenon, but you could say Rosa Bonheur was at the forefront of changing the social perception of how a woman should hold herself in public spaces, and in work. A new woman equaled liberated, being mobile, and able to navigate herself through the world, entering the male public sphere, the male domain, male public arena, she was radical, she was often political especially, where women’s rights were concerned, political organizations such as the suffrage movement began during this period, many women remained single and were well-educated.

Rosa Bonheur lived as a radical new woman as early as the 1850s, because she had built herself a professional career as a painter that was deemed a part of the male domain, and in addition, she was an animal painter, accordingly, this particular classification of painting at the time was definitely seen as a male pursuit, especially in the painting of large animals, if women did paint animals they were seen as painting more domestic animals, Bonheur became the most respected animal painter in France and then elsewhere, she received critical acclaim and became financially self-sufficient by 1853.[2] Bonheur, very often dressed in male clothing, going to horse fairs and slaughterhouses and she had to go and look at animals to get a sense of how to paint them. Women’s period clothing was very constricting, so she approached the police to see if she could get special permission to wear men’s clothing out in public, so it was a stipulation to her allowance that she was only allowed to wear men’s clothing while she was painting or pursuing anything to do with painting when she was not painting she had to wear women’s clothing.[3]

At first glance, this is an image of men taming or riding horses during a fair, in actual fact, this is a self-portrait and Bonheur. She positions herself sitting in the middle of the composition, and she is the only figure with no facial hair, and the only figure making contact with the spectators as if she is trying to tell us something. At first glance she looks like one of the boys and is riding on a brown horse in the middle of white horses, there is a male trying to constrain and control the horse parallel, in the literature of time animals were compared to women and tamers to men and the function of the patriarchal system. The debates concerning animal rights were in process, and much of the arguments stemmed from the control over the bodies of women and animals and the subsequent connections with nature, culture, sexuality, and dominance.[4] The issues of dominance over middle-class women, and working-class men and women coincided with animal rights activists, describing how both dealt with institutionalized authority over their bodies by way of the upper classes.

Additional Resources:

A critical analysis of Bonheur’s work from a contemporary – written in 1871 – http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0202%3Achapter%3D24

David Perkins. Romanticism and Animal Rights. Cambridge University Press, 2003. – ISBN 13 978-0-511-06287-2 ebook

For Fanshawe College students: http://ezpxy.fanshawec.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=120559

The New Woman International: Representations In Photography and Film From the 1870s Through the 1960s. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.9475509.0001.001. Open Access: https://www.fulcrum.org/concern/monographs/sq87bw51m

- Piper, David, and Philip S. Rawson. "Courbet: The Artists Studio." The Illustrated History of Art. London: Bounty, 2005. Print. ↵

- Lecture notes from Sonia Halpern's Art History course 2010 - Western University. ↵

- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435702 ↵

- David Perkins. Romanticism and Animal Rights. Cambridge University Press, 2003. EBSCOhost, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezpxy.fanshawec.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=120559&site=eds-live. ↵