4.7 Modern Russian Movements

Excerpt from: The Creative Spirit: 1550-Present by Elizabeth Cook is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution across the territory of the Russian Empire, commencing with the abolition of the monarchy in 1917, and concluding in 1923 after the Bolshevik establishment of the Soviet Union, including national states of Ukraine, Azebaijan and others, and end of the Civil War.

It began during the First World War, with the February Revolution that was focused in and around Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg), the capital of Russia at that time. The revolution erupted in the context of Russia’s major military losses during the War, which resulted in much of the Russian Army being ready to mutiny. In the chaos, members of the Duma, Russia’s parliament, assumed control of the country, forming the Russian Provisional Government. This was dominated by the interests of large capitalists and the noble aristocracy. The army leadership felt they did not have the means to suppress the revolution, and Emperor Nicholas II abdicated his throne. Grassroots community assemblies called ‘Soviets‘, which were dominated by soldiers and the urban industrial working class, initially permitted the Provisional Government to rule, but insisted on a prerogative to influence the government and control various militias.

A period of dual power ensued, during which the Provisional Government held state power while the national network of Soviets, led by socialists, had the allegiance of the lower classes and, increasingly, the left-leaning urban middle class. During this chaotic period, there were frequent mutinies, protests and strikes. Many socialist political organizations were engaged in daily struggle and vied for influence within the Duma and the Soviets, central among which were the Bolsheviks (“Ones of the Majority”) led by Vladimir Lenin. He campaigned for an immediate end of Russia’s participation in the War, granting land to the peasants, and providing bread to the urban workers. When the Provisional Government chose to continue fighting the war with Germany, the Bolsheviks and other socialist factions exploited the virtually universal disdain towards the war effort as justification to advance the revolution further. The Bolsheviks turned workers’ militias under their control into the Red Guards (later the Red Army), over which they exerted substantial control.[1]

The situation climaxed with the October Revolution in 1917, a Bolshevik-led armed insurrection by workers and soldiers in Petrograd that successfully overthrew the Provisional Government, transferring all its authority to the Soviets. They soon relocated the national capital to Moscow. The Bolsheviks had secured a strong base of support within the Soviets and, as the supreme governing party, established a federal government dedicated to reorganizing the former empire into the world’s first socialist state, to practice Soviet democracy on a national and international scale. Their promise to end Russia’s participation in the First World War was fulfilled when the Bolshevik leaders signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in March 1918. To further secure the new state, the Bolsheviks established the Cheka, a secret police that functioned as a revolutionary security service to weed out, execute, or punish those considered to be “enemies of the people” in campaigns consciously modeled on those of the French Revolution.

Soon after, civil war erupted among the “Reds” (Bolsheviks), the “Whites” (counter-revolutionaries), the independence movements, and other socialist factions opposed to the Bolsheviks. It continued for several years, during which the Bolsheviks defeated both the Whites and all rival socialists. Victorious, they reconstituted themselves as the Communist Party. They also established Soviet power in the newly independent republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia and Ukraine. They brought these jurisdictions into unification under the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1922. While many notable historical events occurred in Moscow and Petrograd, there were also major changes in cities throughout the state, and among national minorities throughout the empire and in the rural areas, where peasants took over and redistributed land.

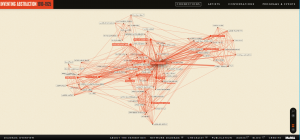

Some of Modern Art’s most notorious artistic practitioners were Russian. Artists who are said to have invented ideas of abstraction, and who influenced multiple art styles and periods across the Western art world, including Canada, in the early twentieth century were; Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandre Rodchenko, El Lisitisky, and avant-garde filmmakers who transformed the experience of cinema, especially Dziga Vertov and his iconic film Man with a Movie Camera. One of the most prolific and influential artists from Russia, who worked within multiple artistic collectives, such as the German collective of Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider Group), and the Bauhaus, Wassily Kandinsky.

Explore the readings and film below to learn about influential Russian artistic and philosophical periods, including Suprematism, Constructivism, Theosophy, and the Avant-Garde.

Kandinsky’s Art in Germany, c. 1910–1937 In Hardiman, Louise, and Nicola Kozicharow. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2018. Internet resource. https://www.merlot.org/merlot/viewMaterial.htm?id=1375032

WATCH FILM

OR you can find a copy with a different soundtrack on archive.org here:

https://archive.org/details/ChelovekskinoapparatomManWithAMovieCamera

or another here https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/114305?vp

For Further Study:

Siegelbaum, Lewis. “Workers’ Clubs.” Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, 29 Jan. 2016, https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1924-2/workers-clubs/.

For information on 19th century Russian Art and Culture view Part Two: Russian Art and Society In Stavrou, Theofanis George. Art and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Indiana University Press, https://publish.iupress.indiana.edu/projects/art-and-culture-in-nineteenth-century-russia