8.3: Installation Art – Research as Practice

What is Installation art? Why is this chapter subtitled Research as Practice?

Fred Wilson – Mining the Museum 1993

Choose to read

Corrin, Lisa G. “Mining the Museum: An Installation Confronting History.” Curator, vol. 36, Dec. 1993, pp. 302–13. https://historyinpublic.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2016/01/Curator_Mining-the-Museum.pdf

Gerald McMaster

McMaster, Gerald R. “INDIGENA: A Native Curator’s Perspective.” Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 3, [Taylor & Francis, Ltd., College Art Association], 1992, pp. 66–73, https://doi.org/10.2307/777350.

Amalia Mesa-Bains

Written by Jennifer Lorraine Fraser – excerpt of graduate studies essay 2016 – edited 2022

Professor emerita, Amalia Mesa Bains is an artist, curator, educator, psychologist, and cultural practitioner. Born Maxine Amalia Mesa in Santa Clara, California in 1943, she was one of two children of Maria Gonzales Mesa and Lawerence Escobedo Mesa.[7] Since the 1960s, Mesa Bains has worked as an artist concurrently with her pedagogical practice. Her work is consistently political and socially constructive. During the Civil Rights era, Mesa Bains established the first public school integrated development program for fellow educators[1] and has received acclaim from the communities she serves, as noted in her 1992 receipt of the MacArthur Fellowship.[2] In 1995, she co-founded the Department of Visual and Public Art at California State University Monterey Bay campus,[3] with a vision to support first-generation college students and those of local low-income communities.[4] Recently, she created a large-scale archival exhibition project ‘consisting of three cabinets of curiosity, entitled the New World Wunderkammer, in The Fowler Museum at UCLA, for their 50th anniversary.[5] This archival display follows her current practice in installation art, bordering on the formation of knowledge through institutional constructs of the library system, museology, and scientific progress.[6]

Mesa Bains’ artistic process stems from a reflection on her childhood and upbringing, the laborious work of her parents, and their individual struggles to become citizens of the United States of America. Their stories are as much a part of Mesa Bains’ cultural endeavors as is her own individual history of resistance and community practice. Now, retired, she is still active in the Californian arts and activist communities.

During the Mexican Revolution of 1916, her father, Lawerence Escobedo Mesa, immigrated to California as a young boy with his mother.[8] As a young man, he worked picking cotton, and in the text Homegrown, (co-authored with bell hooks,) Mesa Bains recalls being a young girl when her father ceased to work as a migrant laborer to begin his career as a ranch hand. This book details how the family transitioned from living in poverty to a lower/middle-class environment and described how their family shared labor while living on the ranch.[9] She states, “Operating as an internally colonized community within the borders of the United States, Chicanos forged a new cultural vocabulary composed of sustaining elements of Mexican tradition and lived encounters in a hostile environment.”[10] Mesa Bains identifies this aspect of sharing labor as important for her contextualization of the Chicano movement later in life.

The Chicano movement was a civil rights endeavour, started by Cesar Chavez,[11] to initiate political mobility within the working class system of Mexican American migrant farmworkers.[12] Fighting for fair pay, fair working conditions, and a decent living, Chicanos conducted marches protesting the Vietnam War, and non-unionized labor practices of the 1960s/70s.[13] Provocatively, Mesa Bains distinguishes between Mexican Americans and Chicano/as, with the latter having a position of political agency to be able to enact, “power and justice to act on behalf of others through the right of dissent and fight.”[14] Moreover, being Chicano/as is a state of being, an identity that is in constant action of “resistance and affirmation – resistance to colonial practices, hegemony and white racism – affirmation in sustaining culture in hostile environments.”[15]

A further distinguishing factor of Mesa Bains’ life and art is the close relationship her family has to the Catholic Church. As a child, Mesa Bains would attend mass for the family, because her mother and father decided to use birth control, and through this, they felt ostracized by the church.[16] Private Mexican-Catholic interiors usually have an area of reverence to the teachings of the bible, acting as a personal altar for the inhabitants of the home. The Church, however, can be considered to some as a hostile environment, negating the spiritual practices of non-Christians and subjugating believers to its teachings.[17] Mexican American women colonized through the church and corresponding religious systems of power and their institutions find spiritual grounding in tending to their own home practices.[18] The altars are metaphorically linked together as “a cosmology of the family-centered in memory that is linked to the present.”[19] Chicana cultural theorist Gloria Anzaldua, describes this as a “breaking down of paradigms and straddling two or more cultures, by creating a new mythos.”[20] For Mesa Bains, her mythos is depicted, translated, and organized into her sculptural installations. The majority of her work either hints at the ideas necessary to construct a home altar or directly references this phenomenon in Mexican/Chicano/a culture. Professor of Visual Studies at UCSC, Jennifer A. Gonzalez describes the home altar as, “most often the responsibility of the matriarch or oldest woman of the household—who uses this sacred space to perform religious, as well as secular rites of rhetoric: supplication, praise, display and memorializing.”[24]

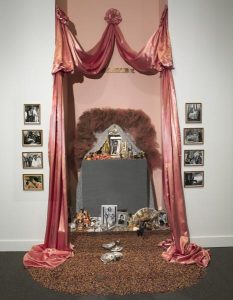

As a Chicana artist, Mesa Bains employs the vocabulary of her home environment to assert meaning into the larger fabric of art practice, and social interactions. Defined as the “Chicano phenomenon of rasquachismo, or the view of the downtrodden,”[21] Mesa Bains states she “began to observe and also create artwork rooted in the everyday or vernacular so much a part of our shared working-class backgrounds.”[22] An Ofrenda for Dolores Del Rio, first fabricated in 1984, and revised in 1991, then again in 2004, is a direct example of this practice. Purchased in 1991, through the Collections Acquisition Program[23] of The Smithsonian American Art Museum, the altar is an installation depicted as a large vanity table, with found objects, glossy images of Mexican Hollywood scarlet Dolores Del Rio, lavish fabric, and multiple mirrors. In 2004, after the death of her mother, Mesa Bains revised the altar and inserted a photograph of her mother into the installation. (Fig. 2) By working with the form of the home altar, Mesa Bains reclaims the spiritual traditions she practiced with her mother and paternal grandmother.[25] She does this as an embodiment of “memory making, history-making,”[26] “and [as] a call to recover and reshape the spiritual identity of the Chicana.”[27] For Mesa Bains, this spiritual identity is embedded in the “laboring body.”[28]

Mesa Bains’ mother, Maria Gonzales Mesa, immigrated to California in the 1920s.[29] When she was a child, her own mother had to give her up as an orphan which left her in the care of a Mexican convent school for a few years.[30] When Gonzales Mesa was a teenager she was reacquainted with her mother and they worked together as domestic workers.[31] Together they would cross into California to work for a day and then return to Mexico, however on one particular day she remained in the US.[32] For the entirety of her working life in the US, she was a domestic worker in the homes of the wealthy. The families she worked for would in turn give her unwanted items, clothing and fabric castoffs, chipped perfume bottles, which returned home to the child Mesa Bains,[33], and later these cast-offs became part of her art as found objects. This act of inserting wealthy unwanted objects into her installations encouraged Mesa Bains to reappropriate the term ‘rasquachismo’ (loosely translated to kitsch for non-chicana critics) and incorporating this practice of bringing the everyday ‘kitsch’ into her art. Accordingly, Mesa Bains describes these found objects as icons of undocumented histories.[34] In so doing, she reimagines these icons as models to reclaim personal and communal power. She states,

As the movimiento model of cultural workers called on Chicano/a artists to dedicate themselves to anti-elite practices that would bring affirmation and pride to the community, the artist engaged in a cultural reclamation through which the traditions of the past could be reanimated in innovative styles.[35]

In An Ofrenda for Dolores Del Rio, Mesa Bains, reclaims the Chicana’s laboring body as a site for what cultural theorist Walter Mignolo refers to as the decolonial gesture, which manifests itself in methods of representation and their corresponding ‘universes of meaning.’[36] Mignolo’s definition of the universe of meaning is the accumulation of inventive narratives, including both ideological constructs of knowledge and their constitutive disciplined practice.[37] However, the gesture, according to Mignolo, “does not lie in the content but in the process and the context.”[38] Mignolo states that “decolonial gestures” would be any and every gesture that directly or indirectly engages in disobeying the dictates of the colonial matrix and contributes to the building of the human species.”[39]

Mesa Bains practice is one that disobeys hegemonic constructs found in American, Mexican, and religious cultures. In her altarpiece she explicitly displaces traditional altar-making practices as a process of revealing colonial and patriarchal misconceptions. Firstly, tending to the spiritual altar is typically a private practice done in the home. Secondly, Mesa Bains combines two different Mexican altar practices into one, those of the altar and the ofrenda.[40] The altar is a space to honor the living members of your friends, family, and struggles experienced in life corresponding to important events.[41] The ofrenda is a temporary structure, typically presented over the ceremony of the Day of The Dead, held from November 1-2, honoring deceased loved ones, and their lived histories.[42] When Mesa Bains began to present altars combining the two forms, the elders in her community cautioned her against it warning of bad luck for the living members of her veneration.[43] By reconstituting the formal elements of the altar, and in making them her own construction of meaning, Mesa Bains is citing a space for the re-emergence of spirituality distant from western idealized forms.

[1] Hooks, Bell, and Amalia Mesa Bains. Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism. Cambridge, MA: South End, 2006. Print. p. 41

[2] Mesa Bains, Amalia. “Artist’s Statement.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80.1 (2012): 3-6. Oxford University Press, Web. 18 Mar. 2015. <http://jaar.oxfordjournals.org/>. P.3

[3] ibid

[4] “About CSUMB.” https://csumb.edu. California State University Monterey Bay. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. <https://csumb.edu/about>.

[5] “New World Wunderkammer: A Project by Amalia Mesa Bains| Fowler Museum at UCLA.” http://www.fowler.ucla.edu, 13 Oct. 2013. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. <http://www.fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/fowler-at-fifty-new-world-wunderkammer>.

[6] “Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead: Amalia Mesa BainsMesa Bains.” Spark. KQED, Northern California. Oct. 2009. Web Video. 12 Apr. 2015 http://www.kqed.org/arts/programs/spark/profile.jsp?essid=25985

[7] Hooks, Bell, and Amalia Mesa Bains. Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism. Cambridge, MA: South End, 2006. Print. p.8

[8] Hooks, Bell, and Amalia Mesa Bains. Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism. Cambridge, MA: South End, 2006. Print. p. 6

[9] ibid

[10] Mesa Bains, Amalia. “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicana Feminisms: A Critical Reader. Ed. Gabriela F Arredondo. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2003. Print p.301

[11] Mesa Bains, Homegrown, p.92

[12] ibid

[13] ibid

[14] Ibid p.137

[15] Ibid p.118

[16] Ibid

[17] Delgadillo, Theresa. Spiritual Mestizaje: Religion, Gender, Race, and Nation in Contemporary Chicana Narrative. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2011. Print. p.2

[18] ibid

[19] Mesa Bains, Homegrown, p.118

[20] Anzaldua, Gloria. “La Conciencia de la Mestiza/Towards a New Consciousness,” in Borderlands/La Frontera. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute. 1987 PDF Web. 28. Mar. 2015 http://www.sfu.ca/iirp/documents/Anzaldua 1999.pdf p.78

[21] Mesa Bains, Amalia. “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicana Feminisms: A Critical Reader. Ed. Gabriela F Arredondo. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2003. Print p300

[22] ibid

[23] “An Ofrenda for Dolores Del Rio.” americanart.si.edu. Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1 May 2012. Web. 15 Apr. 2015. <http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/researchNotes/1998.161.pdf>.

[24] Gonzalez, Jennifer A. “Rhetoric of the Object: Material Memory and the Artwork of Amalia Mesa BainsMesa Bains.” Visual Anthropology Review 9.1 (1993): 82-91. Wiley Online Library. Web. 28 Mar. 2015. <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy library.ocad.ca/doi/10.1525/var.1993.9.1.82/epdf>. P.85

[25] ibid

[26] Mesa Bains, Homegrown,, p.118

[27] “Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead: Amalia Mesa BainsMesa Bains.” Spark. KQED, Northern California. Oct. 2009. Web Video. 12 Apr. 2015 http://www.kqed.org/arts/programs/spark/profile.jsp?essid=25985

[28] Mesa Bains, Homegrown,, p.64

[29] Mesa Bains, Homegrown,, p. 118

[30] Mesa Bains, Homegrown,, p.

[31] ibid

[32] ibid

[33] ibid

[34] Mesa Bains, Amalia. “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicana Feminisms: A Critical Reader. Ed. Gabriela F Arredondo. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2003. Print p.

[35] Mesa Bains, Amalia. “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicana Feminisms: A Critical Reader. Ed. Gabriela F Arredondo. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2003. Print p.

[36] Mignolo, Walter. “Looking for the Meaning of ‘Decolonial Gesture’.” Http://hemisphericinstitute.org/. Duke University Press. Web. 29 Mar. 2015. <http://hemisphericinstitute.org/hemi/en/emisferica-111-decolonial-gesture/mignolo>. p.1

[37] ibid

[38] ibid

[39] ibid p.9

[40] “Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead: Amalia Mesa Bains.” Spark. KQED, Northern California. Oct. 2009. Web Video. 12 Apr. 2015 http://www.kqed.org/arts/programs/spark/profile.jsp?essid=25985

[41] ibid

[42] ibid

[43] Mesa Bains, Homegrown,, p.118

Explore

Duron, Maximiliano. “How to Altar the World: Amalia Mesa-Bains’s Art Shifts the Way We See Art History.” ARTnews.com, ARTnews.com, 9 Jan. 2020, https://www.artnews.com/artnews/news/icons-amalia-mesa-bains-9988/.

Fowler Museum. “New World Wunderkammer: A Project by Amalia Mesa-Bains.” Fowler Museum at UCLA, 23 Feb. 2022, https://fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/new-world-wunderkammer-a-project-by-amalia-mesa-bains/.

Augmented Reality of New World Wunderkammer https://artsandculture.google.com/art-projector/6AFjQVGwU2ppkg?hl=en

Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña: The Couple in the cage

Analysis of Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña’s ‘The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey’ by Rachelle Sanicharan is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Abstract

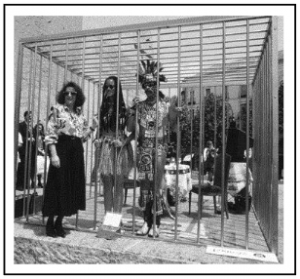

The performance The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña presents a piece mainly featuring two people where presented as a couple, from a fictional island called Guatinaui. The piece performed throughout the world from 1992 to 1994 and in a film in 1993, is narrated from the perspectives of colonial experts who guide the audience through the supposed features of the island, its peoples and the roles the couple played in society. The performance was a response to the quincentennial of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and sought to highlight parts of this history that are often ignored. In this way, one of the main objectives of the performance was to demonstrate the general idea of the Other, and how people from developed countries viewed indigenous communities.

The performance The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña presents a piece mainly featuring two people where presented as a couple, from a fictional island called Guatinaui. The piece performed throughout the world from 1992 to 1994 and in a film in 1993, is narrated from the perspectives of colonial experts who guide the audience through the supposed features of the island, its peoples and the roles the couple played in society. The performance was a response to the quincentennial of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and sought to highlight parts of this history that are often ignored. In this way, one of the main objectives of the performance was to demonstrate the general idea of the Other, and how people from developed countries viewed indigenous communities.

Keywords: Caribbean, Guatinaui Odyssey, Performance Art

Author biography: Rachelle is a fourth-year student as a Canadian Studies Specialist at the University of Toronto. She is an Indo-Guyanese Canadian woman who has a particular interest in researching, recording, and preserving her Indo-Caribbean culture.

Analysis of Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña’s ‘The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey’

The performance The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña presents a piece mainly featuring two people where presented as a couple, from a fictional island called Guatinaui. The piece performed throughout the world from 1992 to 1994 and in a film in 1993, is narrated from the perspectives of colonial experts who guide the audience through the supposed features of the island, its peoples and the roles the couple played in society.[1] Throughout these performances – including some at reputable museums and similar [academic] venues globally – the audience did not know that the couple in the cage that were being showcased, were conducting a performance piece. The performance was a response to the quincentennial of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and sought to highlight parts of this history that are often ignored. In this way, one of the main objectives of the performance was to demonstrate the general idea of the Other, and how people from developed countries viewed indigenous communities. This includes considerations for the gaps in Eurocentric conceptualization of authenticity, identity, and multiculturalism in a world that still views the ‘Other’ as people who need to be subjugated – often caged, controlled, and treated like animals.

The performance allows for one to gain a deeper understanding of authenticity and how it is presented and perceived in the world. Something that was apparent throughout the film was the reaction of observers of the performances around the world really believed the story that was being told, and appeared to enjoy visualizing the entrapment of these two people from an undiscovered island. The performance demonstrated art as “a form of studying the West’s construction of itself through its construction of the Other.”[2] This was clear as the film demonstrated varying positionalities highlighting those who had a problem with two human beings being kept in cages and being treated like animals, and people of colour who related the exhibit to what their ancestors went through.

Whilst there were those who shared their disgust for such an exhibit, there were others who took photos with the two disguised performers, even going as far as to pay for the woman to dance for them or for the man to tell a story in what was presented as the language of Guatinaui. In response, the performers did things like listing cities and places while mixing in Spanish and made up words. These actions demonstrate how the label of Other was used to justify the treatment the two performers received. In addition, the cage had things such as a tv and a radio. With these tools, the performers made a mockery of the whole ideology of the piece by dancing to Rap music and watching TV. The idea of authenticity was pushed aside because of how they were being presented by ‘experts.[3]

Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña used parody as a key feature of the performance, ‘othering’ themselves for the audience, but the viewer of the film too sees the ‘colonial gaze’ and responses of the audience which too becomes a part of the art in the film.[4] This really allowed for a full picture of what was happening during the performance, and the mindset that people had when visiting the exhibit. Some people did question the legitimacy of the exhibit, but most people believed its content because historically, people being presented in cages is something that Western countries have done many times before. Sadly, many did not protest that two people were in cages, and instead actively participated, feeding them like they were animals and photographed them as if they were objects – paying to do so. This demonstrated the skewed perspective the western world has of people labelled as the Other which leads to them being treated as less than a person.

The idea behind creating such a performance that is shown globally, is to demonstrate the skewed perception that people have and to highlight the historical and contemporary labelling of people as the ‘Other’ or subaltern. It is still very present in society today beyond the exhibit and its performance with people of colour often being asked where they are from, simply because of the colour of their skin, or being labelled as exotic because of their race. Similarly, this othering also occurs with cultural displays that are seen as antithesis to western dogma. In the film’s demonstration of people being hesitant when approaching the cage, it also reminds the viewer that the othering that occurs in broader society is often based on fear. Unfortunately, today, we still see how the “West” still fears the ‘Other’ and how they still seek to control and ‘cage’ people, even if it isn’t as apparent as it is shown in this performance.

The performance, The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey, addresses notions of authenticity by showcasing how the idea of the Other is presented to people throughout the world and how the story of the fictional characters was enough to convince many people that a new island and ‘type’ of people had been discovered. For many of these people that was enough to justify why these people were in cages, and that in itself demonstrates how othering often strips people of logic, morals, and humanity.

Works Cited

Behar, Ruth, and Bruce Mannheim. “The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey.” Visual Anthropology Review 11, no. 1 (1995): 118–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1995.11.1.118.

“Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña: The Couple in THE Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West.” Classroom – Art & Education, December 1, 2018. https://www.artandeducation.net/classroom/video/244623/coco-fusco-and-guillermo-gmez-pea-the-couple-in-the-cage-two-undiscovered-amerindians-visit-the-west.

“The Couple in the Cage.” IMDb. IMDb.com, October 10, 1993. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0301136/.

L’Clerc, Lee. “‘The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey/ recording_1.’ .” Lecture, n.d.

Stith, Nathan. “The Performative Nature of Filmed Reproductions of Live Performance.” Theatre Symposium 19, no. 1 (2011): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1353/tsy.2011.0009.

Taylor, Diana. “A Savage Performance: Guillermo Gómez-Peña and COCO Fusco’s ‘ Couple in the Cage.’” TDR/The Drama Review 42, no. 2 (1998): 160–80. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.1998.42.2.160.

https://youtu.be/qv26tDDsuA8

Additional Resources:

VAN SAAZE, VIVIAN. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks. Amsterdam University Press, 2013. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n18r.

van der Meulen, Nicolaj, Wiesel, Jörg and Reinmann, Raphaela. Culinary Turn: Aesthetic Practice of Cookery, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839430316

- Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña. The Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West.” Classroom - Art & Education, December 1, 2018. https://www.artandeducation.net/classroom/video/244623/coco-fusco-and-guillermo-gmez-pea-the-couple-in-the-cage-two-undiscovered-amerindians-visit-the-west ↵

- Behar, Ruth, and Bruce Mannheim. “The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey.” Visual Anthropology Review 11, no. 1 (1995): 118–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1995.11.1.118. ↵

- Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña. The Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West.” Classroom - Art & Education, December 1, 2018. https://www.artandeducation.net/classroom/video/244623/coco-fusco-and-guillermo-gmez-pea-the-couple-in-the-cage-two-undiscovered-amerindians-visit-the-west ↵

- Stith, Nathan. “The Performative Nature of Filmed Reproductions of Live Performance.” Theatre Symposium 19, no. 1 (2011): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1353/tsy.2011.0009. ↵