3.1 Impressionism

Manet and the Impressionists (https://boisestate.pressbooks.pub/arthistory/chapter/manet-impressionists/) – Edited by Jennifer Lorraine Fraser

Édouard Manet

- Édouard Manet, a French painter, was a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism

- His early masterworks, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe) and Olympia, engendered great controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the genesis of modern art.

- His style in this period was characterized by loose brush strokes, simplification of details, and the suppression of transitional tones.

- Manet’s works were seen as a challenge to the Renaissance works that inspired his paintings. Manet’s work is considered “early modern,” partially because of the black outlining of figures, which draws attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

Édouard Manet (1832–1883) was a French painter. One of the first 19th-century artists to approach modern and postmodern-life subjects, he was a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. His early masterworks, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe) and Olympia, engendered great controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the genesis of modern art.

Manet opened a studio in 1856. His style in this period was characterized by loose brush strokes, simplification of details, and the suppression of transitional tones. Adopting the current style of realism initiated by Gustave Courbet, he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1858–59) and other contemporary subjects such as beggars, singers, Gypsies, people in cafés, and bullfights. Music in the Tuileries is an early example of Manet’s painterly style. Inspired by Hals and Velázquez, it is a harbinger of his lifelong interest in the subject of leisure.

The Paris Salon rejected The Luncheon on the Grass for exhibition in 1863. Manet exhibited it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected) later in the year. The painting’s juxtaposition of fully dressed men and a nude woman was controversial, as was its abbreviated, sketch-like handling, an innovation that distinguished Manet from Courbet. At the same time, this composition reveals Manet’s study of the old Renaissance masters. One work cited by scholars as an important precedent for Le déjeuner sur l’herbe is Giorgione’s The Tempest or Titian’s Pastoral Concert from 1509.

The painting, The Luncheon on the Grass, depicts the juxtaposition of a female nude and a scantily dressed female bather on a picnic with two fully dressed men in a rural setting. Rejected by the Salon jury of 1863, Manet seized the opportunity to exhibit this and two other paintings in the 1863 Salon des Refusés, where the painting sparked public notoriety and controversy

As he had in The Luncheon on the Grass, Manet again paraphrased a respected work by a Renaissance artist in his painting Olympia (1863), a nude portrayed in a pose that was based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538). Manet created Olympia in response to a challenge to give the Salon a nude painting to display. His subsequently frank depiction of a self-assured prostitute was accepted by the Paris Salon in 1865, where it created a scandal.

The painting was controversial partly because the nude is wearing some small items of clothing such as an orchid in her hair, a bracelet, a ribbon around her neck, and mule slippers, all of which accentuated her nakedness, sexuality, and comfortable courtesan lifestyle. The orchid, upswept hair, black cat, and bouquet of flowers were all recognized symbols of sexuality at the time. This modern Venus’ body is thin, counter to prevailing standards, and this lack of physical idealism rankled viewers. Olympia’s body as well as her gaze is unabashedly confrontational. She defiantly looks out as her servant offers flowers from one of her male suitors. Although her hand rests on her leg, hiding her pubic area, the reference to traditional female virtue is ironic: female modesty is notoriously absent in this work. As with Luncheon on the Grass, the painting raised the issue of prostitution within contemporary France and the roles of women within society.

The roughly painted style and photographic lighting in these two controversial works was seen by contemporaries as modern: specifically, as a challenge to the Renaissance works Manet copied or used as source material. His work is considered “early modern,” partially because of the black outlining of figures, which draws attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

Impressionism

Impressionism is a 19th-century movement known for its paintings that aimed to depict the transience of light and capture scenes of modern life and the natural world in their ever-shifting conditions.

Key Points

- The term ” impressionism ” is derived from the title of Claude Monet’s painting, Impression, soleil levant (“Impression, Sunrise”).

- Impressionist works characteristically portray overall visual effects instead of details, and use short, “broken” brush strokes of mixed and unmixed color to achieve an effect of intense color vibration.

- During the latter part of 1873, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley organized the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”) to exhibit their artworks independently to mixed critical response.

- The Impressionists exhibited together eight times between 1874 and 1886. The individual artists achieved few financial rewards from the impressionist exhibitions, but their art gradually won a degree of public acceptance and support.

- Impressionists typically painted scenes of modern life and often painted outdoors or en plein air.

- In the middle of the 19th century, the Académie des Beaux-Arts dominated French art, valuing historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits as opposed to landscapes or still life.

- In the early 1860s Monet, Renoir, Sisley, and Bazille met while studying under the academic artist Charles Gleyre. They discovered that they shared an interest in painting landscape and contemporary life rather than historical or mythological scenes.

- Impressionist paintings can be characterized by their use of short, thick strokes of paint that quickly capture a subject’s essence rather than details.

- Impressionist paintings do not exploit the transparency of thin paint films (glazes), which earlier artists manipulated carefully to produce effects.

- Thematically, Impressionist works are focused on capturing the movement of life, or quick moments captured as if by a snapshot.

Impressionism is a 19th century art movement that was originated by a group of Paris-based artists, including Berthe Morisot, Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, as well as the American artist Mary Cassatt. These artists constructed their pictures with freely brushed colors that took precedence over lines and contours. They typically painted scenes of modern life and often painted outdoors. The Impressionists found that they could capture the momentary and transient effects of sunlight by painting en plein air. However, many Impressionist paintings and prints, especially those produced by Morisot and Cassatt, are set in domestic interiors. Typically, they portrayed overall visual effects instead of details, and used short, “broken” brush strokes of mixed and unmixed color to achieve an effect of intense color vibration.

Radicals in their time, early impressionists violated the rules of academic painting. In 19th century France, the Académie des Beaux-Arts (“Academy of Fine Arts”) dominated French art. The Académie was the preserver of traditional French painting standards of content and style. Historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits were valued (landscape and still life were not), and the Académie preferred carefully finished images that looked realistic when examined closely. Color was somber and conservative, and traces of brush strokes were suppressed, concealing the artist’s personality, emotions, and working techniques.

Impressionist painters could not afford to wait for France to accept their work, so they established their own exhibition—apart from the annual salon organized by the Académie. During the latter part of 1873, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley organized the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”) to exhibit their artworks independently. In total, 30 artists participated in their first exhibition, held in April 1874 at the studio of the French photographer and caricaturist Nadar.

The critical response was mixed. Critic and humorist Louis Leroy wrote a scathing review in the newspaper Le Charivari in which, making wordplay with the title of Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant (“Impression, Sunrise”), he gave the artists the name by which they became known. The term “impressionists” quickly gained favor with the public. It was also accepted by the artists themselves, even though they were a diverse group in style and temperament, unified primarily by their spirit of independence and rebellion. They exhibited together eight times between 1874 and 1886. The individual artists achieved few financial rewards from the impressionist exhibitions, but their art gradually won a degree of public acceptance and support. Their dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, played a major role in this as he kept their work before the public and arranged shows for them in London and New York.

The Impressionists captured ordinary subjects, engaged in day-to-day activities in both rural and urban settings. Impressionist artists relaxed the boundary between subject and background so that the effect of an impressionist painting often resembles a snapshot, a part of a larger reality captured as if by chance. They were trying to show the spectacle of Paris and its surrounds that hadn’t been available to the working class before.

Between 1853 and 1870, Napoleon III, nephew of the original Bonapart and the new Emperor, charged his prefect of the Seine, the Baron Haussmann, with the urban renewal project of Paris. Paris in the 19th c. was still a medieval city with narrow, cobbled streets and open sewers with no street lighting in most sections of the city. The urban poor mostly inhabited the central section of Paris and was the population who had fomented and carried out the great Revolution of 1889 and the smaller uprisings of 1830 and 1848. The dark, narrow streets of Paris made it difficult for the government to police those populations. Haussmann would clear the center of Paris of both people and buildings and install the wide, clear boulevards lined with expensive storefronts and apartment buildings for the new bourgeoisie. Sewage would no longer run down the center of the street and modern gas-lights would ensure that modern Paris would truly be “the city of lights.” All of this became the spectacle that for the Impressionists would be what modernism was all about and the subject of many of their paintings.

The development of Impressionism can be considered partly as a reaction by artists to the challenge presented by photography, which seemed to devalue the artist’s skill in reproducing reality. In spite of this, photography actually inspired artists to pursue other means of artistic expression, and rather than compete with photography to emulate reality, impressionists sought to express their perceptions of nature and modern city life.

Scenes from the bourgeois care-free lifestyle, as well as from the world of entertainment, such as cafés, dance halls, and theaters were among their favorite subjects. In their genre scenes of contemporary life, these artists tried to arrest a moment in their fast-paced lives by pinpointing specific atmospheric conditions such as light flickering on water, moving clouds, or city lights falling over dancing couples. Their technique tried to capture what they saw.

In the middle of the 19th century, the Académie des Beaux-Arts dominated French art. The Académie was the preserver of traditional French painting standards of content and style. Historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits were valued; landscape and still life were not. The Académie preferred carefully finished images that looked realistic when examined closely. Paintings in this style were made up of precise brush strokes carefully blended to hide the artist’s hand in the work. Colour was restrained and often toned down further by the application of a golden varnish.

In the early 1860s, four young painters—Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille—met while studying under the academic artist Charles Gleyre. They discovered that they shared an interest in painting landscape and contemporary life rather than historical or mythological scenes. Following a practice that had become increasingly popular by mid-century, they often ventured into the countryside together to paint in the open air, or en plein air, but not for the purpose of making sketches to be developed into carefully finished works in the studio, as was the usual custom. By painting in sunlight directly from nature, and making bold use of the vivid synthetic pigments that had become available since the beginning of the century, they began to develop a lighter and brighter manner of painting that extended further the Realism of Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon School.

Impressionist paintings can be characterized by their use of short, thick strokes of paint that quickly capture a subject’s essence rather than details. Colors are often applied side-by-side with as little mixing as possible, a technique that exploits the principle of simultaneous contrast to make the color appear more vivid to the viewer. Impressionist paintings do not exploit the transparency of thin paint films (glazes), which earlier artists manipulated carefully to produce effects. Additionally, the painting surface is typically opaque and the play of natural light is emphasized.

Thematically, the Impressionists focused on capturing the movement of life, or quick moments captured as if by a snapshot. The representation of light and its changing qualities were of the utmost importance. Ordinary subject matter and unusual visual angles were also important elements of Impressionist works. Note the factory in the background – another symbol of the modern life the Impressionists were trying to capture.

Impressionist Sculpture

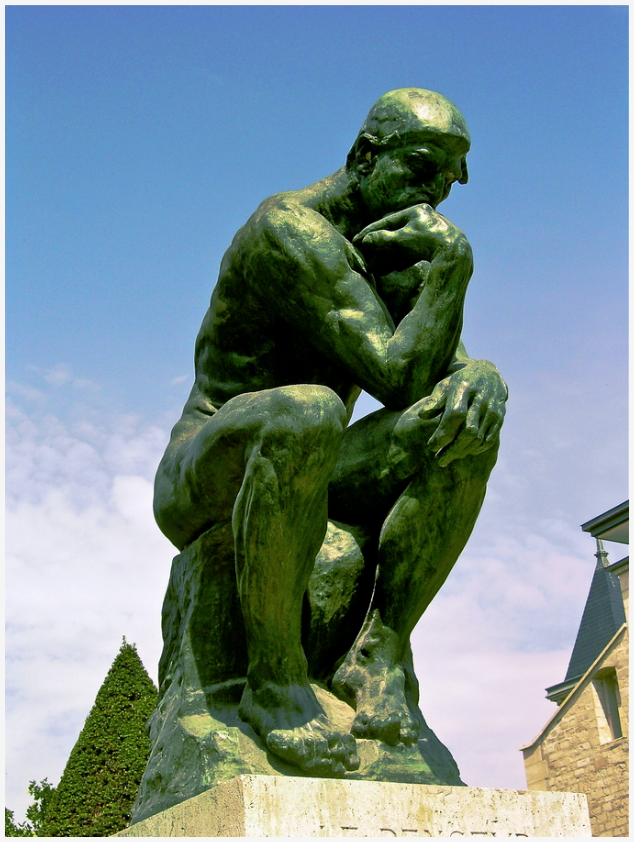

Modern sculpture is generally considered to have begun with the work of French sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Key Points

- Typically, modernist artists were concerned with the representation of contemporary issues as opposed to grand historical and allegorical themes previously favored in art. Rodin modeled complex, turbulent, deeply pocked surfaces into clay and many of his most notable sculptures clashed with the predominant figure sculpture tradition, in which works were decorative, formulaic, or highly thematic. The spontaneity evident in his works associates him with the Impressionists, though he never identified as such.

- Rodin’s most original work departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory in favor of modeling the human body with realism, and celebrating individual character and physicality.

- It was the freedom and creativity with which Rodin used these practices, along with his more open attitude toward bodily pose, sensual subject matter, and non-realistic surface, that marked the re-making of traditional 19th century sculptural techniques into the prototype for modern sculpture.

- Though his work crossed many stylistic boundaries, and he did not identify as an Impressionist specifically, Degas is nonetheless regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism.

- The sculpture Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, by Edgar Degas c. 1881 was shown in the Impressionist Exhibition of 1881 and drew a great deal of controversy due to its departures from historical precedent, a key motive of the Impressionists.

French Sculpture

Modern classicism contrasted in many ways with the classical sculpture of the 19th century, which was characterized by commitments to naturalism, the melodramatic, sentimentality, or a kind of stately grandiosity. Several different directions in the classical tradition were taken as the century turned, but the study of the live model and the post-Renaissance tradition was still fundamental. Modern classicism showed a lesser interest in naturalism and a greater interest in formal stylization. Greater attention was paid to the rhythms of volumes and spaces—as well to the contrasting qualities of surface (open, closed, planar, broken, etc.)—while less attention was paid to storytelling and convincing details of anatomy or costume. Greater attention was given to psychological effect than to physical realism, and influences from earlier styles worldwide were used.

Modern sculpture, along with all modern art, “arose as part of Western society’s attempt to come to terms with the urban, industrial and secular society that emerged during the 19th century.” Typically, modernist artists were concerned with the representation of contemporary issues as opposed to grand historical and allegorical themes previously favored in art.

Rodin’s Influence

Modern sculpture is generally considered to have begun with the work of French sculptor Auguste Rodin. Rodin, often considered a sculptural Impressionist, did not set out to rebel against artistic traditions, however, he incorporated novel ways of building his sculpture that defied classical categories and techniques. Specifically, Rodin modeled complex, turbulent, deeply pocketed surfaces into clay. While he never self-identified as an Impressionist, the vigorous, gestural modeling he employed in his works is often likened to the quick, gestural brush strokes aiming to capture a fleeting moment that was typical of the Impressionists. Rodin’s most original work departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory, in favor of modeling the human body with intense realism, and celebrating individual character and physicality.

Rodin was a naturalist, less concerned with monumental expression than with character and emotion. Departing with centuries of tradition, he turned away from the idealism of the Greeks and the decorative beauty of the Baroque and neo-Baroque movements. His sculpture emphasized the individual and the concreteness of flesh, suggesting emotion through detailed, textured surfaces, and the interplay of light and shadow. To a greater degree than his contemporaries, Rodin believed that an individual’s character was revealed by his physical features. Rodin’s talent for surface modeling allowed him to let every part of the body speak for the whole. The male’s passion in The Kiss, for example, is suggested by the grip of his toes on the rock, the rigidness of his back, and the differentiation of his hands. Rodin saw suffering and conflict as hallmarks of modern art. He states that “nothing, really, is more moving than the maddened beast, dying from unfulfilled desire and asking in vain for grace to quell its passion.”

Rodin’s major innovation was to capitalize on such multi-staged processes of 19th-century sculpture and their reliance on plaster casting. Since clay deteriorates rapidly if not kept wet or fired into a terra-cotta, sculptors used plaster casts as a means of securing the composition they would make out of the fugitive material that is clay. This was common practice among Rodin’s contemporaries: sculptors would exhibit plaster casts with the hopes that they would be commissioned to have the works made in a more permanent material. Rodin, however, would have multiple plasters made and treat them as the raw material of sculpture, recombining their parts and figures into new compositions and new names. As Rodin’s practice developed into the 1890s, he became more and more radical in his pursuit of fragmentation, the combination of figures at different scales, and the making of new compositions from his earlier work.

It was the freedom and creativity with which Rodin used these practices—along with his activation of the surfaces of sculptures through traces of his own touch—that marked Rodin’s re-making of traditional 19th-century sculptural techniques into the prototype for modern sculpture.

Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas was a French artist famous for his paintings, sculptures, prints, and drawings. He is especially identified with the subject of dance; more than half of his works depict dancers. He is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism, although he rejected the term, preferring to be called a Realist.

During his life, public reception of Degas’s work ranged from admiration to contempt. As a promising artist in the conventional mode, Degas had a number of paintings accepted in the Salon between 1865 and 1870. He soon joined forces with the Impressionists, however, and rejected the rigid rules, judgments, and elitism of the Salon—just as the Salon and general public initially rejected the experimentalism of the Impressionists.

Degas’ work was controversial but was generally admired for its draftsmanship. His La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans, or Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, which he displayed at the sixth Impressionist Exhibition in 1881, was probably his most controversial piece; some critics decried what they thought its “appalling ugliness” while others saw in it a “blossoming.” The sculpture is two-thirds life size and was originally sculpted in wax, an unusual choice of medium for the time. It is dressed in a real bodice, tutu, and ballet slippers and has a wig of real hair. All but a hair ribbon and the tutu are covered in wax. The 28 bronze repetitions that appear in museums and galleries around the world today were cast after Degas’ death. The tutus worn by the bronzes vary from museum to museum.

Recognized as an important artist in his lifetime, Degas is now considered one of the founders of Impressionism. Though his work crossed many stylistic boundaries, his involvement with the other major figures of Impressionism and their exhibitions, his dynamic paintings and sketches of everyday life and activities, and his bold color experiments served to finally tie him to the Impressionist movement as one of its greatest artists.

Attribution:

Introduction To Art by Muffet Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Review: https://smarthistory.org/europe-19th-century/impressionism/impressionism-a-beginners-guide/