4.5 Futurism

Futurism

The futurist movement was launched in Italy in 1909 under the leadership of the charismatic poet F.T. Marinetti. Concerned that Italy was lagging behind the industrial advances of countries such as Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, the Futurists wanted to “fast forward” their nation into the forefront of modernization, by breaking all ties to the past. For this reason, the Futurists advocated the destruction of all ties to the past (including libraries and museums):

Futurist Manifesto, 1909

Futurism as a Political Movement

The Futurists aggressively campaigned for a revolution in art and society, and they publicized their ideas in “manifestos” (imitating political manifestos) that were widely circulated in the press:

Museum of Modern Art

They also famously embraced war and revolution as a means of social cleansing:

Sotheby’s. “Futur! Futurism.” YouTube, uploaded by Sotheby’s, 1 November 2013, https://youtu.be/lJTzl9ee-0k

Guggenheim Museum. “Futurist Performance and F.T. Marinetti.” YouTube, uploaded by Guggenheim Museum, 9 December 2016, https://youtu.be/5NzgSJCZ7g4

The Futurist movement was not limited to art: there were Futurist Manifestos issued for Music, Architecture, Photography, Cinema, and Fashion! The one thing they had in common was a radical break with the past, and an equally radical rejection of accepted cultural values.

The Futurists pioneered modern music through the invention of music “machines,” and the concept of music as “noise.” Luigi Russolo proposed a new form of “music” based on the sound of machines and industry. In his manifesto, The Art of Noises (1913), he wrote:

Luigi Russolo, “The Art of Noises,” 1913

The industrial revolution had created an entirely new form of sound, and Russolo proposed to harness this sound as the basis for a new form of music:

Luigi Russolo, “The Art of Noises,” 1913

Futurist music has been compared to Heavy Metal and Punk. Like these musical styles, the Futurists rejected traditional notions of “beauty” and embraced the raw sounds of the modern industrial environment.

Listen to recording of Rusollo’s noise music at Ubuweb.

Lisboa, Museu Coleção Berardo. “Luigi Russolo, Intonarumoris, 1913” YouTube, uploaded by david rato, 1 July 2012, https://youtu.be/BYPXAo1cOA4

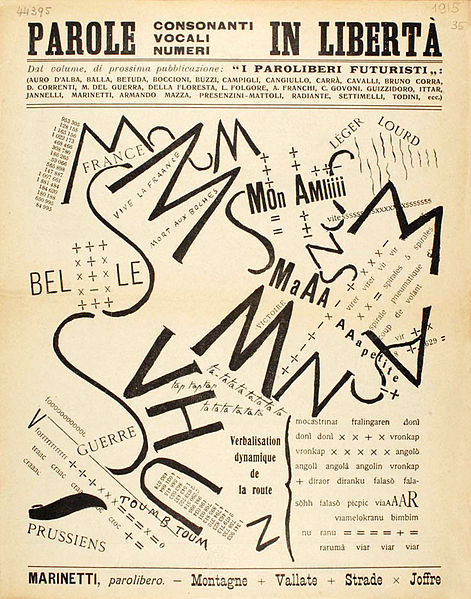

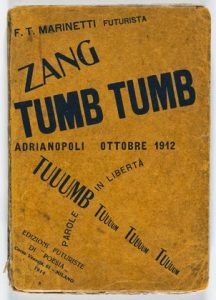

The Futurists also inspired a revolution in poetry and typography. Marinetti’s “words in liberty” sought to free words from conventional syntax, grammar, and meaning. In his poems and typographic designs words became “sounds” and “visual forms” rather than signifiers of meaning.

Museum of Modern Art

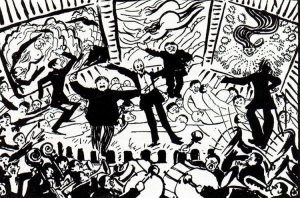

The Futurists pioneered “performance” as an art form, and their public appearances (what they called “serata”) were rarely polite affairs. They typically involved recitations of noise poems, and performances of noise music, along with declamations from manifestos, and irreverent acts such as burning the Austrian flag. The goal was to incite the audience to riot, and Marinetti judged his performance to be a success only if a fight broke out. Violence and mayhem were welcome remedies to what the futurists regarded as bourgeois complacency.

Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

Futurist art embraced the themes of movement, dynamism, and speed:

Rosalind McKever, Umberto Boccioine, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (Khan Academy)

In this work Giacomo Balla creates the sensation of motion through repeated forms:

In strip cartoons, multi-limbed figures appear all the time. They stand for bodies who are running or flapping or just for people who are doing a lot of things simultaneously, in a terrible rush. The multiplication and motion effect has allowed pictures to extend their repertoire enormously, to overcome their stasis in all kinds of ways . . . . [In this picture] A lady is walking a dog; a widow and her pet. The lady has roughly 15 feet, variably solid and see-through. The dog has eight countable tails, while its legs are lost in flurry of blurry overlays. Four swinging leads go between them. The picture’s sense of movement (if that is what it actually is) is created out of stark black forms and weird flowing lacey veils.”

Tom Lubbock, “Great Works: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash,” The Independent, September 4, 2009

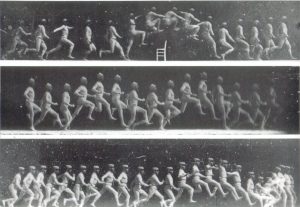

Balla was influenced by contemporary photographers who used stop-action cameras to capture motion. Anticipating the invention of the moving image (film) photographers like Edward Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey used multiple cameras fitted with a fast acting shutter. The resulting photographs are like the individual frames of a moving image. Balla endeavoured to create the same effect of motion by multiplying the limbs of his figures.

Étienne Jules Marey. “Étienne Jules Marey – L’Homme Machine” YouTube, uploaded by meisenstrasse, 17 June 2009, https://youtu.be/kMh7GI9pEIY

Museum of Modern Art

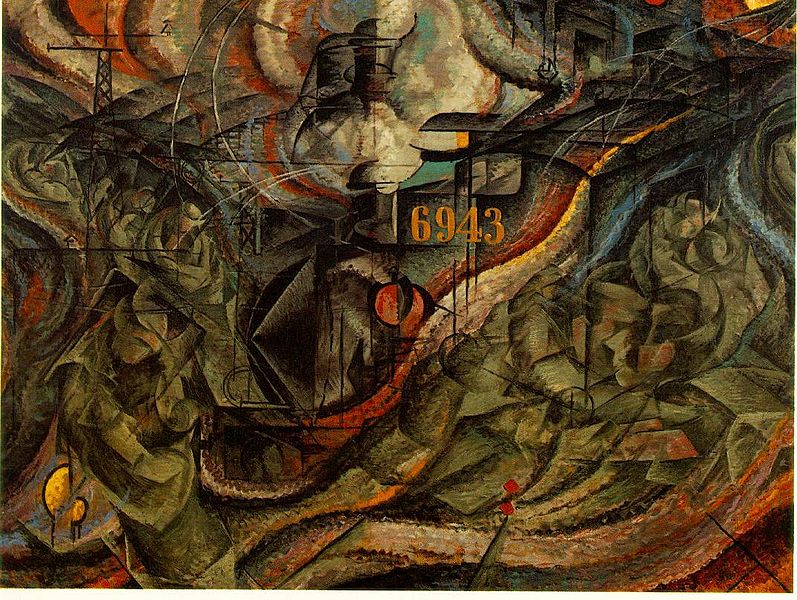

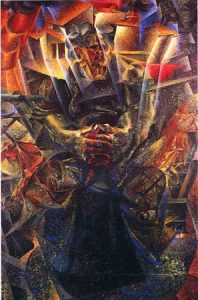

Cubism also helped Futurists represent motion, speed, and simultaneity. In this work, Boccioni uses Cubist fragmentation to evoke the dynamism and energy of a speeding locomotive:

Museum of Modern Art

The Museaum of Modern Art. “1913 | “Dynamism of a Soccer Player” by Umberto Boccioni” YouTube, uploaded by MoMA, 10 January 2013, https://youtu.be/GLEJgVSL0Ac

Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris

This painting by Luigi Russolo depicts a speeding automobile (a favourite subject of the Futurists). He creates the sensation of movement by fragmenting the object and the atmosphere around it into waves that resemble the scientific principal know as the Doppler Effect. This short video will explain it:

Alt Shift X. “The Doppler Effect: What does motion do to waves?” YouTube, uploaded by Alt Shift X, 6 June 2013, https://youtu.be/h4OnBYrbCjY

Museum of Modern Art

The defining work of the Futurist movement was Umberto Boccioni’s Unique forms of Continuity in space. It was an update on a famous sculpture of a striding man by Auguste Rodin. As the figure strides forward, the forms of his body unfold, creating a rushing surge of motion forward:

Museum of Modern Art

Italian Futurism: An Introduction

Can you imagine being so enthusiastic about technology that you name your daughter Propeller? Today we take most technological advances for granted, but at the turn of the last century, innovations like electricity, x-rays, radio waves, automobiles and airplanes were extremely exciting. Italy lagged Britain, France, Germany, and the United States in the pace of its industrial development. Culturally speaking, the country’s artistic reputation was grounded in Ancient, Renaissance and Baroque art and culture. Simply put, Italy represented the past.

In the early 1900s, a group of young and rebellious Italian writers and artists emerged determined to celebrate industrialization. They were frustrated by Italy’s declining status and believed that the “Machine Age” would result in an entirely new world order and even a renewed consciousness.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the ringleader of this group, called the movement Futurism. Its members sought to capture the idea of modernity, the sensations and aesthetics of speed, movement, and industrial development.

A manifesto

Marinetti launched Futurism in 1909 with the publication his “Futurist manifesto” on the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro. The manifesto set a fiery tone. In it Marinetti lashed out against cultural tradition (passatismo, in Italian) and called for the destruction of museums, libraries, and feminism. Futurism quickly grew into an international movement and its participants issued additional manifestos for nearly every type of art: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, photography, cinema—even clothing.

The Futurist painters—Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini, and Giacomo Balla—signed their first manifesto in 1910 (the last named his daughter Elica—Propeller!). Futurist painting had first looked to the color and the optical experiments of the late 19th century, but in the fall of 1911, Marinetti and the Futurist painters visited the Salon d’Automne in Paris and saw Cubism in person for the first time. Cubism had an immediate impact that can be seen in Boccioni’s Materia of 1912 for example. Nevertheless, the Futurists declared their work to be completely original.

Dynamism of Bodies in Motion

The Futurists were particularly excited by the works of late 19th-century scientist and photographer Étienne-Jules Marey, whose chronophotographic (time-based) studies depicted the mechanics of animal and human movement.

Étienne Jules Marey. “Étienne Jules Marey – L’Homme Machine” YouTube, uploaded by meisenstrasse, 17 June 2009, https://youtu.be/kMh7GI9pEIY

A precursor to cinema, Marey’s innovative experiments with time-lapse photography were especially influential for Balla. In his painting Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, the artist playfully renders the dog’s (and dog walker’s) feet as continuous movements through space over time.

Entranced by the idea of the “dynamic,” the Futurists sought to represent an object’s sensations, rhythms and movements in their images, poems and manifestos. Such characteristics are beautifully expressed in Boccioni’s most iconic masterpiece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (see above).

The choice of shiny bronze lends a mechanized quality to Boccioni’s sculpture, so here is the Futurists’ ideal combination of human and machine. The figure’s pose is at once graceful and forceful, and despite their adamant rejection of classical arts, it is also very similar to the Nike of Samothrace.

Politics & War

Futurism was one of the most politicized art movements of the twentieth century. It merged artistic and political agendas in order to propel change in Italy and across Europe. The Futurists would hold what they called serate futuriste, or Futurist evenings, where they would recite poems and display art, while also shouting politically charged rhetoric at the audience in the hope of inciting riot. They believed that agitation and destruction would end the status quo and allow for the regeneration of a stronger, energized Italy.

These positions led the Futurists to support the coming war, and like most of the group’s members, leading painter Boccioni enlisted in the army during World War I. He was trampled to death after falling from a horse during training. After the war, the members’ intense nationalism led to an alliance with Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party. Although Futurism continued to develop new areas of focus (aeropittura, for example) and attracted new members—the so-called “second generation” of Futurist artists—the movement’s strong ties to Fascism has complicated the study of this historically significant art.

Read

Learn more:

Futurism

- Tumultous Assembly: Visual Poems of the Italian Futurist. Getty Museum

- Futurism. Smarthistory

- Futurist Manifestos

- Futurism. Guggenheim Museum

- Words in Freedom: Futurism at 100. MOMA

- Tumultuous Assembly: Visual Poems of the Italian Futurists. Getty Museum

Italian Futurism: An Introduction

Read: Alberto Sposito. “Balla and Depero in Architecture.” Agathón. https://doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/1172017. Accessed 31 Aug. 2022. https://www.agathon.it/agathon/article/view/24/25

Attributions

Futurism in Art 109 Renaissance to Modern by Dr. Melissa Hall for Westchester Community College is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial.

Italian Futurism: An Introduction by Emily Casden for SmartHistory is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike