2.10 Victorian Photography

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, The Artist’s Studio / Still Life with Plaster Casts – DR. Kris Belden-Adams

By modern standards, nineteenth-century photography can appear as a relic of the past. While the stark black and white landscapes and unsmiling people have their own austere beauty, these images also challenge our notions of what defines a work of art. Photography is a controversial fine art medium, simply because it is difficult to classify—is it an art or a science? Nineteenth-century photographers struggled with this distinction, trying to reconcile aesthetics with improvements in technology.

Although the principle of the camera was known in antiquity, the actual chemistry needed to register an image was not available until the nineteenth century.

Artists from the Renaissance onwards used a camera obscura (Latin for dark chamber), or a small hole in the wall of a darkened box that would pass light through the hole and project an upside-down image of whatever was outside the box. However, it was not until the invention of a light-sensitive surface by Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce that the basic principle of photography was born.

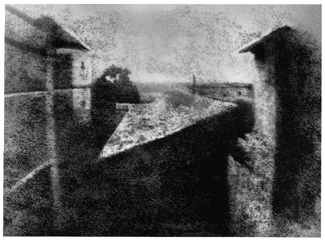

From this point the development of photography largely related to technological improvements in three areas, speed, resolution and permanence. The first photographs, such as Niépce’s famous View from the Window at Gras (1826) required a very slow speed (a long exposure period), in this case about 8 hours, obviously making many subjects difficult, if not impossible, to photograph. Taken using a camera obscura to expose a copper plate coated in silver and pewter, Niépce’s image looks out of an upstairs window, and part of the blurry quality is due to changing conditions during the long exposure time, causing the resolution, or clarity of the image, to be grainy and hard to read. An additional challenge was the issue of permanence, or how to successfully stop any further reaction of the light sensitive surface once the desired exposure had been achieved. Many of Niépce’s early images simply turned black over time due to continued exposure to light. This problem was largely solved in 1839 by the invention of hypo, a chemical that reversed the light sensitivity of paper.

Technological improvements

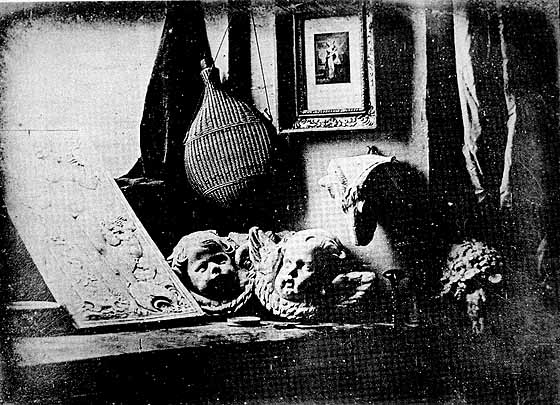

Photographers after Niépce experimented with a variety of techniques. Louis Daguerre invented a new process he dubbed a daguerreotype in 1839, which significantly reduced exposure time and created a lasting result, but only produced a single image. Like many of the founding inventors of photography, Daguerre—a Parisian theatrical scene-painter/designer and showman—saw this new medium as part-art, part-science. This image of Daguerre’s own studio (he was a practicing artist), testifies to photography’s scientific achievement (resulting from incessant experiments with photochemistry, partly to find a way to make a permanent image) as it also implicitly argues for photography’s merit as an art medium by providing a link between photography and a traditional still-life painting.

The still life is a genre of subjects in artworks that involves inanimate objects, arranged to evoke symbolic associations. The subjects of The Artist’s Studio / Still Life with Plaster Casts lend themselves to visual analysis using the elements of art and principles of composition. Framed by drapery in the corner of his studio, a wicker-covered bottle hangs near a framed artwork just above the center of the frame, both surrounded by plaster casts of the heads and tiny wings of two putti (center), the head of a ram (center-right), and a panel bearing a nude female (possibly Venus) in low relief, flanked by a pushy Cupid (left edge).

Daguerre’s combination of objects obediently remained still for the duration of the long exposure (an estimated 15–20 minutes), but also displayed a remarkably wide range of tonal values, variegated textures, highlights, and shadows to add visual interest. Vertical architectural framing is offset by compositional diagonals to move the viewer’s eye dynamically through the image. In other words, Daguerre did not set up and make this photograph solely to test his photochemistry, but to accentuate the artistic value of his subject matter—and by extension, to highlight the artistic value of the new medium he helped create.

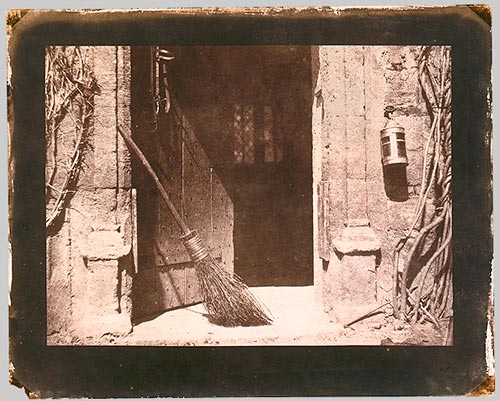

At the same time, Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with his what would eventually become his calotype method, patented in February 1841. Talbot’s innovations included the creation of a paper negative, and new technology that involved the transformation of the negative to a positive image, allowing for more that one copy of the picture. The remarkable detail of Talbot’s method can be seen in his famous photograph, The Open Door (1844) which captures the view through a medieval-looking entrance. The texture of the rough stones surrounding the door, the vines growing up the walls and the rustic broom that leans in the doorway demonstrate the minute details captured by Talbot’s photographic improvements.

The collodion method was introduced in 1851. This process involved fixing a substance known as gun cotton onto a glass plate, allowing for an even shorter exposure time (3-5 minutes), as well as a clearer image.

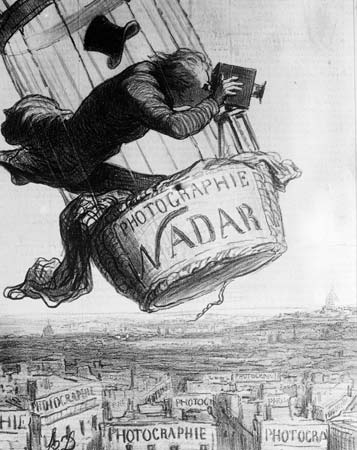

The big disadvantage of the collodion process was that it needed to be exposed and developed while the chemical coating was still wet, meaning that photographers had to carry portable darkrooms to develop images immediately after exposure. Both the difficulties of the method and uncertain but growing status of photography were lampooned by Honoré Daumier in his Nadar Elevating Photography to the Height of Art (1862). Nadar, one of the most prominent photographers in Paris at the time, was known for capturing the first aerial photographs from the basket of a hot air balloon. Obviously, the difficulties in developing a glass negative under these circumstances must have been considerable.

Further advances in technology continued to make photography less labor intensive. By 1867 a dry glass plate was invented, reducing the inconvenience of the wet collodion method.

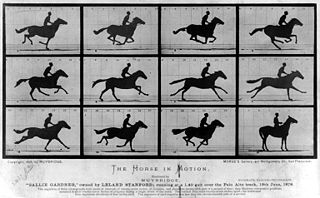

Prepared glass plates could be purchased, eliminating the need to fool with chemicals. In 1878, new advances decreased the exposure time to 1/25th of a second, allowing moving objects to be photographed and lessening the need for a tripod. This new development is celebrated in Eadweard Muybridge’s sequence of photographs called Galloping Horse (1878). Designed to settle the question of whether or not a horse ever takes all four legs completely off the ground during a gallop, the series of photographs also demonstrated the new photographic methods that were capable of nearly instantaneous exposure.

Finally, in 1888 George Eastman developed the dry gelatin roll film, making it easier for film to be carried. Eastman also produced the first small inexpensive cameras, allowing more people access to the technology. These cameras known as the Brownie cameras were invented and patented by Frank A. Brownwell of Vienna, Ontario, Canada. (The same small town Thomas Edison’s family first lived in before being forced to flee to the United States.)

Photographers in the 19th century were pioneers in a new artistic endeavor, blurring the lines between art and technology. Frequently using traditional methods of composition and marrying these with innovative techniques, photographers created a new vision of the material world. Despite the struggles early photographers must have had with the limitations of their technology, their artistry is also obvious.

Women, Urban Culture, and Photography

Please Read

Additional resources:

The First Photograph from the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

A Thumbnail History of the Daguerreotype

Niépce: The Reference Website about the Inventor of Photography

Eadweard Muybridge’s Photography of Motion

The Wizard of Photography: The Story of George Eastman and how he Transformed Photography

About Honoré Daumier (National Gallery of Art)

Mitchell Leslie, “The Man Who Stopped Time” in Stanford Magazine, 2001

Freeze Frame: Eadweard Muybridge’s Photography of Motion (National Museum of American History)

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License