How do we picture a shifting urban landscape constantly on the verge of disappearing? Stan Douglas’s 14-foot-long panoramic photograph of one block of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighborhood addresses this difficulty, documenting every building in exacting detail. But just as important in Douglas’s photograph is what goes unseen and uncaptured by the camera: the human subjects that usually populate the street, the pressures of real estate speculation on housing, and the shifting identity of the city in the lead-up to the 2010 Olympic Games. Though the image is a careful study of a specific place, the photograph offers us evidence of how Vancouver is impacted by global forces that are shaping city streets everywhere.

Gentrification, protest, and the landscape

Taken at night and theatrically illuminated with soundstage lighting, Every Building on 100 West Hastings captures an otherwise unremarkable city block with remarkable clarity. The neighborhood pictured has been called “the poorest postal code in Canada” and is the site from which dozens of women, many of them Indigenous, have disappeared (the remains of many of them were subsequently discovered on convicted serial killer Robert Pickton’s farm in 2002). Vancouver has prospered in the past few decades thanks to international trade and the success of the tech and film industries, but the Downtown Eastside neighborhood, operates as a point of contrast for the rest of the city, where poverty, homelessness, drug use, and sex work have increased as the divide between the rich and poor deepens. [1]

Digitally stitched together from twenty-one separate photographs, Douglas’s panoramic view of the block would be impossible to replicate with natural sight. With the camera aimed squarely at each building façade, the image allows us to take in the entirety of the streetscape without bending the horizon line, or losing focus. Its massive scale encourages our eye to skip along the length of the street, noticing that hotels, pawnshops and convenience stores are the most common surviving businesses, while six lots are either for sale or lease by realtor Fred Yuen, hinting at the economic downturn the neighborhood has experienced. Handmade signs in shop windows advertise closing sales, pawnshops offer to “buy, sell, or trade” goods, convenience stores announce ATMs and cheap cigarettes, and two closed circuit cameras surveil the left-hand street corner outside Jaysons Food Market.

At the time Douglas made the image, the neighborhood was on the verge of another change, however, represented by the coming of the Olympic Games to Vancouver in 2010. Fierce debates were raging between residents, city officials and real estate developers about whether it would be possible to “clean up” the Downtown Eastside in time for the international event, and over the future of the Woodwards department store, located immediately across the street, behind Douglas’s camera. Closed due to increased competition from American big-box stores, local residents occupied the building to demand it be converted into affordable housing rather than condominiums, culminating in a stand off between police, developers and local activists in 2002 known as Woodsquat. Every Building on 100 West Hastings does not picture these events, but by devoting such large-scale attention to a neighborhood whose future was contested, Douglas’s image raised questions about the value of the landscape for local communities (a community that includes the artist himself, whose studio is located only three blocks from the site of the photograph).

Missing bodies and the ethics of documentary photography

Unlike photojournalistic images of the neighborhood, which show sidewalks busy with cars and people, Douglas photographs an empty West Hastings Street. While this is usually a bustling street, even late at night, the artist blocked off the sidewalk with city permits to photograph its sidewalks empty of people. If you look closely, temporary “no parking” signs dot the lampposts in the image.

Without human subjects in the scene, the photograph recalls documentation of Hollywood film sets and studio constructions of city façades, referencing Vancouver’s history as “Hollywood North,” an affordable stand-in for American cities in movies and television series. But removing the neighborhood residents from the camera’s gaze is also a response to decades-long questions about the ethics of street photography, particularly when documenting poorer urban areas. The Downtown Eastside was often depicted in news media across Canada at the time Douglas was working, but while photojournalists frequently turned the camera’s lens towards the neighborhood’s unhoused residents, the artist purposely removes them from view. By obscuring human subjects from his frame, Douglas avoids the potential of re-victimizing local residents a second time, through the invasive view of the camera, as photographer Martha Rosler once famously argued in her landmark essay on the ethics of documentary photography in the Bowery neighborhood of Manhattan.

Some of the bodies missing from the block were forcefully disappeared, however, by police enforcement of anti-loitering laws, or more nefariously, drug overdoses and the disappearances and deaths of women involved in sex work. Douglas’s ability to control the movement of bodies across the streetscape has led several commentators to question if a problematic power dynamic is still at play between the photographer and his un-pictured subjects. It is telling that, in 2003, the Vancouver Book Award was presented as a tie between Heroines by Lincoln Clarkes—a series of black and white photographs, inspired by 1990s fashion advertising of unnamed women subjects in the Downtown Eastside—and a small catalogue devoted to Every Building on 100 West Hastings produced by the Contemporary Art Gallery: a tie that speaks to the charged place the Downtown Eastside occupied in citizens’ imaginations. While Douglas’s photograph imaged a city block that was poised to be transformed by unseen actors (either gentrified by developers or reclaimed by the community), Clarkes’s series seemed to re-center the neighborhood’s fate on its individual residents, using the established language of photojournalism to expose them as victims.

Conceptual photography in Vancouver

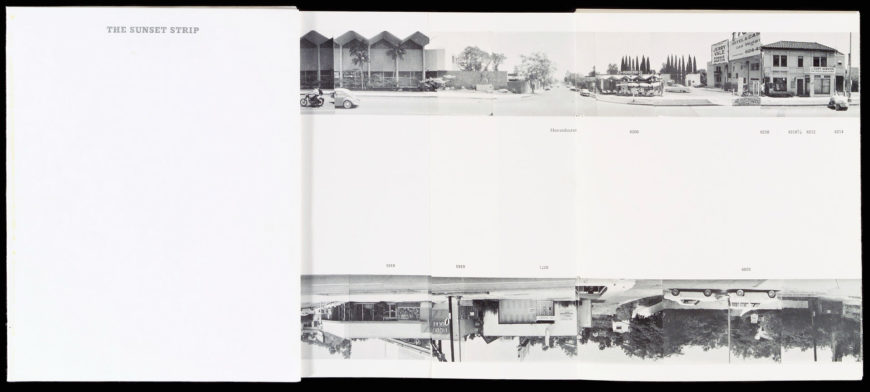

Though taken well before the invention of Google Street View, Douglas’s image evokes a similar perspective of a city block as seen out the window of a car. This viewpoint is not accidental: the title and structure of Douglas’s photograph is borrowed directly from a famous photo book, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, by American conceptual artist, Ed Ruscha. In his accordion-style fold out book published in 1966, Ruscha took black and white photographs of every building along the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles and placed them side by side to create a panorama of both sides of the street. Though Douglas borrows Ruscha’s title and structure for his image, his choice of aesthetic is strikingly different. While Ruscha was interested in making a banal, black-and-white document of vernacular architecture, copying amateur photography and inhabiting the role of the “non-artist” to challenge the artist-as-genius narrative of modernist formalism, Douglas borrows the visual language of commercial film studios to capture the block in vivid, full color detail. In this way, Douglas’s photograph responds to the flow of ideas between West Coast conceptual artists, like Ruscha, and artists in the so-called Vancouver School of photo-conceptualism.

One of the hallmarks of the Vancouver School’s approach is the use of cinematic conventions in fine art photographs. The theatrical lighting used in Douglas’s nighttime image would be familiar to many Vancouver residents accustomed to seeing film crews cordoning off public space for television shows and movies. But unlike his contemporary, Jeff Wall, whose cinematographic photographs are often staged in Vancouver, but are not meant to depict Vancouver (or anywhere), in Douglas’s photographs, the location plays itself. Detroit is Detroit, Cuba is Cuba, and Vancouver is Vancouver in Douglas’s studies of the urban landscape. He nevertheless connects local conditions to global forces in each of these series, demonstrating the ways the landscape is transformed in response to the pressures of globalization, capitalism and urban renewal.

Notes

- See Jeff Sommers and Nicholas Blomley, “The Worst Block in Vancouver.” Every Building on 100 West Hastings. Vancouver: Contemporary Art Gallery, 2002, pp. 19–58.

Additional resources

Burnham, Clint. 2005. “No Art After Pickton.” Fillip, 1 (1), pp. 1–3.

Every Building on 100 West Hastings. 2002. Reid Shier, ed. Vancouver: Contemporary Art Gallery.

INTERTIDAL: Vancouver Art and Artists. 2005. Dieter Roelstrate and Scott Watson (eds.). Antwerp: Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen.

Mansoor, Jaleh. 2005. “Ed Ruscha’s ‘One-Way Street,’” October 111 (Winter), pp. 127–142.

Modigliani, Leah. 2018. Engendering an Avant-Garde: The Unsettled Landscapes of Vancouver Photo-Conceptualism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Moser, Gabrielle. 2011. “Phantasmagoric Places: Local and Global Tensions in the Circulation of Stan Douglas’s Every Building on 100 West Hastings,” Photography & Culture 4:1 (March), pp. 55–72.

O’Brian, Melanie., 2007. “Introduction: Specious Speculation,” in Melanie O’Brian (ed.), Vancouver Art & Economies. Vancouver: Artspeak/Arsenal Pulp Press, pp. 11–26.

Roelstraate, Dieter. 2013. “Apparation Theory: Stan Douglas and Photography,” in Stan Douglas, Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, pp. 103–109.

Rosler, Martha. 1993. Rosler, Martha. “In, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)” in The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press), pp. 303–341.

Ruins in Process: Vancouver Art in the Sixties, The Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at The University of British Columbia, and the grunt gallery

Sommers, Jeff and Nicholas Blomley, 2002. “The Worst Block in Vancouver.” Every Building on 100 West Hastings. Vancouver: Contemporary Art Gallery, pp. 19–58.

Vancouver Anthology: The Institutional Politics of Art, Stan Douglas, ed., 2nd edition (Vancouver: Or Gallery/Talon Books, 2009)

Jeff Wall, “‘Marks of Indifference’: Aspects of Photography in, or as, Conceptual Art,” in Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer, eds. (Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, 1995): pp. 247–267.

Watson, Scott. 1991. “Discovering the Defeatured Landscape,” Vancouver Anthology, Stan Douglas, ed. (Vancouver: Talonbooks/Or Gallery), pp. 246–265.

Esma Mohamoud

Esma Mohamoud