8.4 Disorienting the Art World: Mona Hatoum in Istanbul – Jo Applin

Jo Applin, “Disorienting the Art World: Mona Hatoum in Istanbul”, British Art Studies, Issue 3, https://dx.doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/japplin – CC BY-NC International 4.0

In 1995 the German curator René Block was invited to curate the 4th International Istanbul Biennial. Titled “Orient/ation: The Vision of Art in a Paradoxical World”, Block eschewed the national groupings employed by most biennials, instead tackling head-on the idea of what nationality might mean in a climate of increasing global mobility in which the art world comprised an “international diaspora of artists”. 1 Block’s poster for the Biennial was a hastily hand-drawn compass, its coordinates marked deliberately incorrectly. West was labelled North, South-East read as South- West, and the North-East was renamed “Istanbul”. According to this compass there is no one central point or locale relative to which its cardinal points of north, south, east, and west can make sense. 2

Block wanted to draw attention to the ways in which events such as the Istanbul Biennial tend always to be framed in relation to the central power blocs of Western Europe or North America. By placing the “Orient”—with all its nostalgic, romantic, racist, and ideologically charged associations—at the centre of the Biennial’s world-map, Block’s aim was to re-orient, or rather, to disorient the art world, and to remap its familiar coordinates. Block paid particular attention to Turkey’s geographical neighbours, inviting artists from Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Macedonia, Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, and the newly formed Balkan states.

Block also invited a mix of ten younger and more senior figures from the then-thriving British art scene, seven of whom were women, and five of whom were born outside the United Kingdom—Anish Kapoor in Mumbai, Shirazeh Houshiary in Iran, Zaha Hadid in Iraq, Ceal Floyer in Pakistan, and Mona Hatoum in Beirut—in one more complicated twist on how viewers might begin to think about—or rethink—the idea of nationality, “Britishness”, and the geopolitics of home and belonging. Less than a handful of those selected were affiliated with the then-dominant “Young British Artists” (or YBAs); a phenomenon that since the late 1980s had stood for a very particular, increasingly jingoistic formulation of “British” art that ran counter to Block’s attempt to disrupt, rather than affirm, ideas of national identity.

Hatoum was a generation older than the YBAs, and her practice was a world apart from Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin’s dystopic vision of a beer-soaked, bawdy Albion. On the contrary, Hatoum’s work addressed the condition of rootlessness, rather than a rooted sense of belonging, and while she drew freely on her own experience as an exilic subject born in Lebanon to Palestinian parents, she has always, rightly, insisted that her work should not be reduced to only that interpretative framework.

In 1975, when she was in her twenties, Hatoum paid a short visit to London. While she was there civil war broke out in Lebanon, making it impossible for Hatoum to return. Forced to remain, the artist enrolled for undergraduate studies at the Byam Shaw School of Art, after which she went on to study at

the Slade. English was to become her third language, after Arabic, which she had always spoken at home, and French, which she’d spoken at school.

Hatoum’s homesickness became a key motif for her ensuing work, most powerfully articulated in her important video-piece Measures of Distance (1988), in which Hatoum reads aloud in English some letters from her mother, the Arabic text of the originals being superimposed over images of her mother taken in the shower. While Hatoum’s exilic status is foregrounded in many of her works, her growing reputation from the late 1980s onwards assured for her a standing in the London art world that was, significantly, far from that of an “outsider”.

In Istanbul, Hatoum showed two rectangular floor-bound works that were very much in keeping with her practice in London at that time. Pin Carpet and Prayer Mat (fig. 1 and 2) were both covered with neat, tightly aligned rows of sharp pins; stainless steel in the case of Pin Carpet, and nickel-plated in the case of Prayer Mat. Both glisten when the light catches them. Prayer Mat was the smaller of the two, measuring about one metre in length, while Pin Carpet measured over one metre wide by approximately two-and-a-half metres long. The rug or carpet was a format Hatoum returned to several times over the coming years, recalling a longer interest in post-sixties sculptural practice, such as the Minimalist floor-pieces of Carl Andre, or Eva Hesse’s latex “rugs” such as Schema and Sequel on which she balanced loose rubbery balls that might—like Hatoum’s glass-marble “map” carpets—roll free and disintegrate if touched. Hatoum enjoyed the sense of dislocation and the complex muddle of the familiar and the unfamiliar that the rugs offered, which, as with the best of Hatoum’s work, both conceptually and literally served to wrong-foot viewers.

In 1996 Hatoum made Doormat, a domestic doormat complete with the word “WELCOME” spelled out across the middle in hundreds of bristling stainless steel pins, glued to stand upright in uniform rows running along the horizontal length of the mat. Doormat is at once welcoming and frightening, a binary which Hatoum frequently exploits in her work. That the domestic is typically cast as the traditional realm of the female subject was a point not lost on Hatoum, who would have been all too aware of the complexities of this situation when installing her work in a largely Islamic culture, in which the daily prayer ritual performed at the local mosque tends to be attended largely by men, with many women instead performing their prayers at home. Although for Block Hatoum’s works offered “a sharp commentary on the situation of women in the Orient”, Hatoum, as ever, was resistant to the idea that her work could be reduced to any one specific meaning. 3 For Hatoum her work spoke to universals as much as particulars, and while for some critics the constant reference to her place of birth and exiled status has proven the driving force in how to think about her work, the artist is always quick to offer other, often more expansive themes that concern her; of home, not “her” home; of violence, not civil war; of women, not this one particular woman. Of her works for the Istanbul Biennial, Hatoum has said:

A carpet is supposed to give you comfort and protect you from the cold of the floor. From a distance this carpet looks like it is made of plush velvet, a very inviting shimmering surface. When you approach it, you realise it is made of millions of sharp stainless steel pins pushed upwards through a canvas backing. I showed it at the Istanbul Biennale in the Aya Ireni church along with another smaller mat. 4

Hatoum refers here to Pin Carpet, which she placed in the by-then decommissioned Aya Ireni church. It was the first church built in Constantinople, and remained the city’s central place of worship until Hagia Sofia was first dedicated in 360 AD. The second “smaller mat” Hatoum refers to is Prayer Mat, which also had a shiny, pin-studded surface. The thought of standing, kneeling, or sitting on either carpet is an uneasy one. As Hatoum put it, her rugs and carpet works operate through “a kind of attraction/ repulsion”; at turns suggestive of a magic carpet or prayer mat or, from a Western perspective, of a doormat designed to wipe one’s feet clean. 5

Inset among the pins of Prayer Mat was a small compass. As well as recalling the overarching theme of the Biennial, the compass here serves a specific, and not just metaphorical, function. It is there to assist the worshipper who must face in the direction of Mecca when praying, and the mat is always situated as such. Travelling prayer mats with in-built compasses are readily available to purchase, as Hatoum would have been aware—any number of shops on London’s Brick Lane stock similar items; slightly kitsch, yet helpful, aids for Muslims located far from Mecca’s geographic location in Saudi Arabia who may be on the move, or away from home travelling and in need of assistance in locating their coordinates from their current position. 6 Hatoum’s two mats, one in an historically Christian place of worship, the other explicitly referencing Islam, could be considered bookends framing Hatoum’s Christian upbringing within a Muslim culture. However, they point also to a wider geopolitical situation addressed in other works made by Hatoum from around this time, in which cultural motifs are taken not as given but as mobile and open to interpretation. To whom is the invitation to pray extended? And what are we to make of that invitation, suffused as it is with a threat of violent damage to one’s body? Hatoum prefers to leave the question open and unanswered: poetics, not polemics, guide the political implications of her work. While Hatoum has often spoken of the powerful impact made on her by the Palestinian writer Edward Said’s 1984 essay, “Reflections on Exile”, the coordinates of her work have never been confined solely to those of “east” versus “west”. 7 Like Block she wanted to disorient

and so re-orient attention elsewhere, away from “nationality” as either straightforward or important in the final analysis of the work. Said, in turn, wrote an essay about Hatoum’s work in which he suggested that

An abiding locale is no longer possible in the world of Mona Hatoum’s art which . . . articulates so fundamental a dislocation as to assault not only one’s memory of what once was, but how logical and possible, how close and yet so distinct from the original abode, this new elaboration of familiar space and objects really is. 8

Hatoum’s practice both exploits and confounds binary oppositions by redeploying them in ways that are at once specific and allusive, personal and playful. Her work is never explicit. Rather, Hatoum prefers to work in the gaps between making and meaning, saying that any work of art that “obviously reveals itself” and its “intentions” is “boring”. 9

Another early work by Hatoum titled Light Sentence (1992), in which a single light bulb swings in a grid of mesh lockers to throw menacing, mobile shadows, is frequently described as a political work that speaks of the refugee camp, of confinement, and indeed disorientation. And yet, as Farah Nayeri has pointed out, the artist frequently finds viewers coming to her work “with this preconceived idea of where I come from, and therefore what I’m putting in my work, and they tend to over-interpret the work in relation to my background”. 10

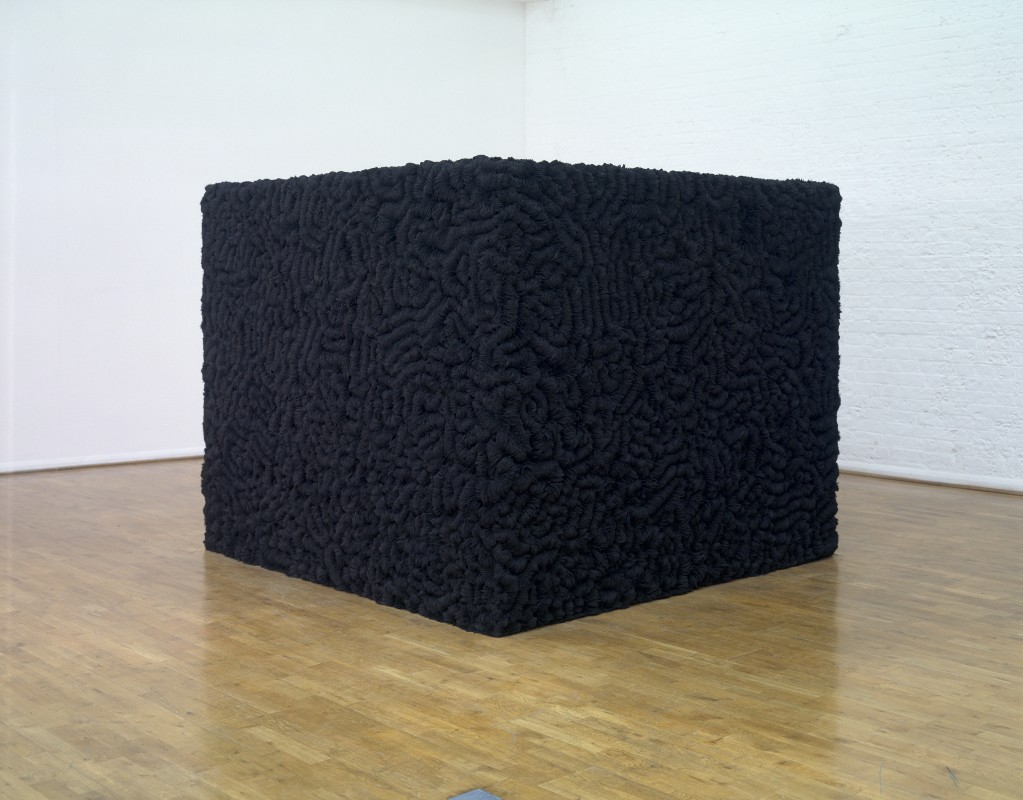

At the centre of a compass is found a magnet, an object that operates according to the same logic of attraction and repulsion as many of Hatoum’s works. It is magnetism that allows the compass needle to establish its coordinates, and to position us in the world. Magnets seek similarity, not difference (the south pole of a magnet is always attracted to another south pole). Place a north- and south-seeking pole near by and they will repel one another, refusing contact or connection. Three years before the Istanbul Biennial, Hatoum had made another work that used magnetic forces to counter global ones. Formally the work was an ambivalent “homage” to Piero Manzoni’s 1961 sculpture Socle du Monde, in which the Italian artist placed a sculptural plinth upside down on the ground as if supporting the weight of the world. In Hatoum’s reworking, or rather re-worlding of Manzoni’s sculptural base, every surface of the magnetic pedestal was covered in a writhing sea of iron filings, dotted with clustered islands (fig. 3). If you held an opposing magnet close to the surface, the filings started to ripple and move. In contrast to Manzoni’s proposal, the base of the world in Hatoum’s work was not fixed and solid, but mobile and responsive, liable to change and subject to human as well as material forces.

Crucially, the pins that make up the surface of both Prayer Mat and Pin Carpet are also magnetic. The magnet functions in these works both as a material conduit and also as an apt metaphor for both Hatoum’s and Block’s global politics, which set out to disorient an art world that remained attracted to sameness rather than difference, and which complacently treated nationality and cultural difference as irreconcilable, polar certainties rather than unsettled and staying that way. Hatoum insists that her own biography neither explains nor wholly accounts for the kinds of worlds her work seeks to invoke and produce; so too the position of her Islamic prayer mat in a church in Istanbul refuses to resolve or settle as either political or personal, polemic or poetic. Like the needle on a compass, Hatoum’s aim with works such as Prayer Mat is to orient and disorient viewers in equal measure. By the same measure, Hatoum’s status as a leading British artist who looks outwards rather than inwards, has defined her critical engagement with a globalizing contemporary art world, even as she insists upon, and continues to assert, the grounded nature of her art, as signalled by her various site- specific works and frequent international residencies. 11 Place matters, as does our embodied relationship to that place and to the materials and objects comprising our lived environment, wherever in the world that may be.

I would like to thank Mona Hatoum for her help in the preparation of the essay.

Footnotes

- See the website of the Istanbul Biennial, accessed 12 Aug. 2015: http://bienal.iksv.org/en/archive/biennialarchive/213

- See Arthur C. Danto’s catalogue essay for the 1995 Istanbul Biennial, “Art and the Discourse of Nations: Reflections on Biennial of Nations”, in 4th International Istanbul Biennial: Orient/ation: The Vision of Art in a Paradoxical World (Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, 1995), in which he to addresses Block’s motif of the compass.

- René Block, “Is it Possible to Create Works that Aren’t Art?”, in 4th International Istanbul Biennial: Orient/ation, 20–35 (25, 29).

- Mona Hatoum, personal correspondence to Chiara Bertola, 2015.

- Janine Antoni, “Mona Hatoum [interview]”, BOMB 63 (Spring 1998): http://bombmagazine.org/article/2130/mona- hatoum

- Guy Brett has also described these works in his “Survey”, in Michael Archer, Guy Brett, and Catherine de Zegher, Mona Hatoum (London: Phaidon, 1997), 77.

- See Edward Said, “The Art of Displacement: Mona Hatoum’s Logic of Irreconcilables”, in Said and Sheena Wagstaff,

Mona Hatoum: The Entire World as a Foreign Land, exh. cat. (London: Tate Publishing, 2000), 7–19.

- Said, “Art of Displacement”, 7–19 (15).

- Antoni, “Mona Hatoum [interview]”.

- Farah Nayeri, “The Many Contradictions of Mona Hatoum”, New York Times, 7 July 2015.

- Although the geopolitics of the artist residency is not quite so straightforward as such an “exiled” or outsider position might seem. On the politics of the artist as global “nomad”, see James Meyer, “Nomads: Figures of Travel in Contemporary Art”, in Site-Specificity: The Ethnographic Turn, ed. Alex Coles (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2001).

Bibliography

Antoni, Janine. “Mona Hatoum [interview].” BOMB 63 (Spring 1998): http://bombmagazine.org/article/2130/mona-hatoum

Block, René. “Is it Possible to Create Works that Aren’t Art?” In 4th International Istanbul Biennial: Orient/ation: The Vision of Art in a Paradoxical World. Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, 1995.

Brett, Guy. “Survey.” In Michael Archer, Guy Brett, and Catherine de Zegher. Mona Hatoum. London: Phaidon, 1997.

Danto, Arthur C. “Art and the Discourse of Nations: Reflections on Biennial of Nations.” In 4th International Istanbul Biennial: Orient/ation.

Said, Edward. “The Art of Displacement: Mona Hatoum’s Logic of Irreconcilables.” In Said and Sheena Wagstaff, Mona Hatoum: The Entire World as a Foreign Land. London: Tate Publishing, 2000, 7–19.