11.2 Appropriation Art in the Instagram Age – Siobhan Lyons

Camera Copia: Reflections on Rephotography in the Instagram Age

by Siobhan Lyons – https://nanocrit.com/issues/issue10/camera-copia-reflections-rephotography-instagram-age

Published December 2016 – NANO: New American Notes Online by https://nanocrit.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The idea of appropriation-as-art is not at all new; one of the most notable examples of stylistic borrowing in the photography industry is that of Anne Zahalka’s “Sunbather” (1989), which deliberately replicates the form and technique of Max Dupain’s “Sunbaker” (1937). With subtle deviations from the original, appropriation belongs to a distinctly postmodern outlook of art. While Andy Warhol used appropriation of famous images as a comment on popular culture in the 1960s and 70s, the actual term appropriation developed in the 1980s, and is predominantly associated with artists such as Sherrie Levine, Jeff Koons, and Barbara Kruger. Levine in particular is, as Hayley Rowe argues, the most notable appropriation artist: “Levine worked first with collage, but is most known for her work with re-photography – taking photographs of well-known photographic images from books and catalogues, which she then presents as her own work.” While there is no official first use of the term re-photography, it can be seen to have emerged by the late 70s and early 80s.

Not to be confused with the act of taking a repeat photograph of the same site after a certain time period, the use of re-photography in this article refers to the act of photographing a pre-existing photograph. In 1979, Levine re-photographed a 1936 work by photographer Walker Evans. As Rowe notes, Levine’s work “did not attempt to edit or manipulate any of these images, but simply capture them.” Rowe furthermore argues that “she was advancing the art form that is photography by using it to increase our awareness of already existing imagery. On a basic level, we tend to equate originality with aesthetic newness. Why should a new concept—the concept of appropriation and the utilising of existing imagery—be deemed unoriginal?” Rowe’s position accords with Marcus Boon’s views on copying as essentially human and potentially original. Using the term copia, from the Roman goddess of abundance, to refer to a kind of artistic style circulating around “abundance, plenty [and] multitude” (41), Boon argues in his work In Praise of Copying (2010), that “copying is a fundamental part of being human” (7). The act of copying, for Boon, “is a part of how the universe functions and manifests” (7). In fact, Boon argues that the internet has radically altered conceptions of property and originality: “What the internet offers us is […] the opportunity to render visible once more the instability of all the terms and structures which hold together existing intellectual-property regimes, and to point to the madness of modern, capitalist framings of property” (245). He furthermore states that “the concept of an original could not exist without that of a copy, and, in practice, ‘originality’ was not an objective fact but a historically specific style of presentation” (49).

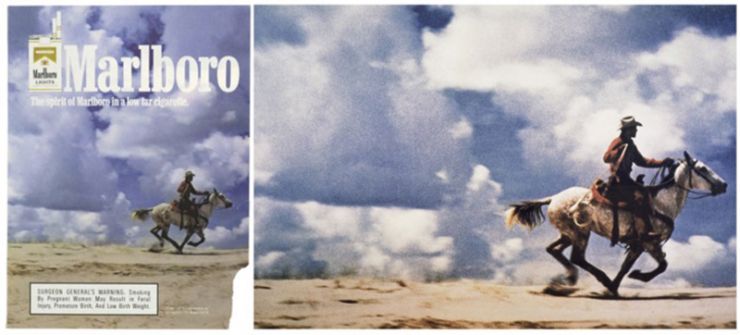

Yet as online photography-sharing networks such as Flickr and Instagram have gained traction in the last few years, undoing the amateur/professional hierarchy, questions of originality have resurfaced and continue to generate debate. One of the most famous cases in recent years is Richard Prince’s rephotographing of a number of photographers’ works. Famously, Prince began his career by rephotographing Sam Abell’s iconic cowboy photos for the American Marlboro advertisements. Also produced in 1989 alongside Zahalka’s “Sunbather,” ten years after Levine’s “Walker Evans” rephotograph, Prince cropped the famous image of the cowboy astride a horse in the American West and renamed it “Cowboy” (1989). Of this incident, Abell stated: “It’s obviously plagiarism” (qtd. in Samuels, “Photographer Sam Abell Talks”). Prince has since sold this work for millions of dollars at Sotheby’s (Samuels, “Photographer Sam Abell Talks”) while also profiting in recent years from social media through rephotographing the works of others on Instagram, much to the vexation of its users. Prince has routinely been at the center of much legal and ethical controversy in recent years, prompting renewed debate as to the status of originality in the photography world, and whether it is still a shared value. Is taking a picture of an already-existing photograph plagiarism? Or is there some semblance of originality in the act of rephotographing that aligns more with Boon’s views on copying? This paper addresses those cases that exemplify the growing discord around the virtue of originality, how networks such as Instagram have challenged such conceptions, and whether or not budding photographers value originality as their predecessors did.

Instagram, launched in October 2010 by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, has enabled both amateur and professional photographers to share images and videos with greater ease. Despite its popularity, however, Hu, Manikonda, and Kambhampati argue that relatively little scholarly attention has been paid to Instagram. This is especially true with regard to its legitimacy as an organization. The service is still predominantly in its infancy, which is reflected in the lack of actual scholarly research devoted to its ethical implications. Discussions regarding copyright issues have, however, been conducted online, regarding proper use of images, re-invoking the issues surrounding originality.

Yet debates regarding the status and legitimacy of appropriation as a potential art form have been circulating for a number of decades, ever since photography as both practice and art form became more widespread in the twentieth century. Such arguments are further problematized by the notion that photography itself initially confronted and dispelled ideas of originality for the sake of objectivity. In 1974, for instance, Richard Christopherson asked, “Can art be made by machines?” While Douglas Crimp notes that we have seen “the triumph of photography-as-art” (96), Mary Marien notes that many photographers repeatedly tried to incorporate different techniques into their practice in order to “negate the criticism that photography was witlessly automatic and therefore not an art” (450). More recently, however, arguments surrounding the extent to which photography can perfectly replicate and reproduce reality have been readily shut down, and the arguments against photography as art all but abandoned. Although as Potts argues, a central assumption surrounding photography was that “photography represented the world in a truthful, objective manner” (75), Roland Barthes argues in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980) that “the Photograph is unary when it emphatically transforms ‘reality’ without doubling it” (41). Essential to our understanding about originality and plagiarism is the relationship between photography and reality; in transforming reality without doubling it, Barthes acknowledges the photographer’s ability to creatively re-depict a scene without reproducing it, thereby alluding to the inherent creativity in an individual photograph. Hence the notion of photography as art, rather than as an objective reproduction of reality, informs these debates on the photograph as potentially original.

Abell’s Marlboro photograph became iconic and is considered by many to be a work of art, despite being an advertisement. In Art Worlds (1982), Howard S. Becker writes that in order for art photography to make a name for itself, it first had to remove itself from “nonartistic enterprises” such as advertising, and “cut its ties to the world of commercial photography” (340). The frenzy that followed Prince’s rephotograph of Abell’s work, however, suggests that such advertisements fall under the rubric of photographic art. Abell himself noted that he was not angry by Prince’s actions, but nor was he amused, saying that Prince has broken “the golden rule” of photography. He also states:

A photograph of mine could never be the Guggenheim museum, could never be on the cover of their guide, couldn’t be on the cover of the D.A.P. catalogue, and that is because editorial photography for the most part is considered by those entities, by the Guggenheim and by the art establishment to be not worthy. But copied by someone else it is worthy. So the art world has something to answer for, and I look forward to their answer. (Qtd. in Samuels, “Photographer Sam Abell Talks About ‘Cheeky’ Richard Prince”)

Abell’s views offer useful insight into the problems with contemporary plagiarism, showing how the industries are as much to blame as the artists themselves. Although the expectation for photographs to be original declined with the rise of postmodern discourse, photography was still considered an art form. In fact, many artists saw the appropriated work as superior in artistic quality to the original. Since the 1960s, appropriation-as-art in sculpture and photography gained a number of supporters, notably Prince’s contemporaries such as Cindy Sherman and Jeff Koons. Yet in his 2007 review of Prince’s work, Peter Schjeldahl claimed that the works of Sherman and Koons “are better, for stand-alone works of originality, beauty, and significance” (“The Joker: Richard Prince at the Guggenheim”).

With its origins in postmodern thought (as well as in Dada photography), appropriation was, in some circles, considered a form of art in and of itself, one that deliberately dismantled popular conceptions about authorship and attribution that had been persistently upheld in the art world since Romanticism and celebrated in Modernism. In photography, this concept was all the more prominent. From the 1970s onwards, concerns relating to originality were partially alleviated. As Marien argues, critics such as Douglas Crimp, Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster “focused on the demise of the original as a vastly important sign that modernism, with its enthronement of artistic expression and originality, was also dying” (434). Similarly, writer Jackie Higgins writes: “Modernist production gives way to postmodernist reproduction” (58).

Douglas Crimp argued that while photography was invariably seen as a form of art for the postmodernists, it was defined by a sense of nonconformity where style, intention and aesthetics were concerned: “the photographic activity of postmodernism operates, as we might expect, in complicity with these modes of photography-as-art, but it does so only in order to subvert and exceed them” (98). Debora Halbert makes a similar point in Perspectives on Plagiarism and Intellectual Property in a Postmodern World (1999): “A postmodern strategy is to avoid playing by the rules and attempt to expand our understanding of creation, commodification, and property law. However, when brought to court the postmodernist will (evidently) lose” (116). Such was the case (initially) for photographer Richard Prince. Prince has been at the center of controversy ever since he established a habit of rephotographing already-existing photographs in 1975; while the “Cowboy” photograph is arguably the most notable appropriation incident in Prince’s career, his work was declared unlawful in December 2008 by US District Judge Deborah A. Batts in a judgment over what was deemed improper use of the work of artist Patrick Cariou, who filed a suit against Prince. Prince had used over 30 of Cariou’s photographs in his exhibition Canal Zone. However, in 2013, Judge Batt’s ruling was reversed by the US Court of Appeals, which stated that the images were altered just enough so that the exhibition did not constitute copyright infringement. In 2014, an out-of-court settlement was made (Boucher).

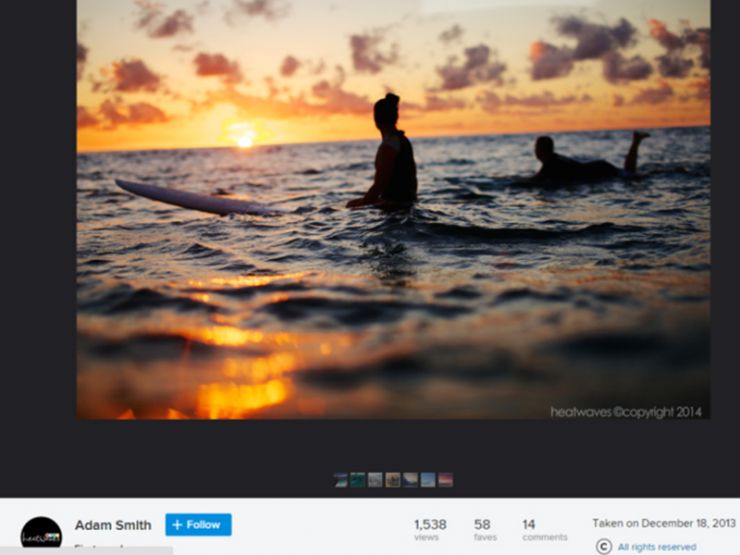

Prince has continued to use and alter the work of other photographers and artists, much to the vexation of both aspiring and established photographers online. An Instagram user named Doe Deere, for example, posted a photograph of herself with blue hair holding a blue-haired Pidgin doll on her account. When she discovered that her photograph appeared in one of Prince’s exhibitions, having sold for over $90,000, she took to her Instagram account and stated:

Figured I might as well post this since everyone is texting me. Yes, my portrait is currently displayed at the Frieze Gallery in NYC. Yes, it’s just a screenshot (not a painting). No, I did not give my permission and yes, the controversial artist Richard Prince put it up anyway. It’s already sold ($90K I’ve been told) during the VIP preview. No, I’m not gonna go after him. And nope, I have no idea who ended up with it! (qtd. in Samuels, “How Richard Prince Sells”).

The incident has been the subject of many articles, particularly in photography outlets like DIY Photography. In his article for DIY Photography, Liron Samuels openly disparages Prince’s work, calling it “lazy” art and pointing out the copyright issues that would automatically apply to Instagram users, saying: “If you were to take a screen shot of someone’s Instagram account and try selling it, two things would happen. The first is that you’d be told you’re violating the copyright of the photographer whose photo you’re selling, and secondly you’d be laughed at” (“How Richard Prince Sells”). He also argues: “It turns out, though, that if you’re famous enough you can take such a screen shot and not only bypass copyright but also make a fortune doing so.” The consensus regarding Prince’s status as a photographer appears unanimously disapproving in online photography forums. On Digital Photography Review, a page titled “Richard Prince is a jerk face” has attracted comments on the matter of Instagram and copyright, with one user writing:

I’m pretty much convinced at this point that he is deliberately spitting in the eye of the appellate court in Cariou. That court found that an appropriation that merely comments on a work (as opposed to transforms it) is not fair use. So what did he do? He made works where all he did was comment on the original, and did not transform it. I for one think he needs a good hard slap in the courts. (SpinOne)

Prince was also the target of Paddy Johnson in her Art World article “Richard Prince Sucks” (2014), saying: “We can trace appropriation precedents back to Warhol, and Prince as an early adopter, but who cares? Copy-paste culture is so ubiquitous now that appropriation remains relevant only to those who have piles of money invested in appropriation artists.” Johnson’s comments are on par with those of Mary Marien’s in Photography: A Cultural History (2002), namely that appropriation has, since the 1990s, become a tedious technique in photography. She argues: “by the mid-1990s, appropriation itself was mocked as a worn-out visual device, as when Amy Adler photographed her own drawing of Sherrie Levine’s appropriation of a photograph by Edward Weston” (450). Indeed, for many theorists, the postmodern celebration of artful copying at the expense of originality, in effect criticizing the integrity of originality, has since lost its novelty. Warhol’s artwork was undertaken at a time when the discourse of the self-as-commodity was gaining popularity, undermining the more modernist view that the artist and the artwork alike were meaningful repositories of significant meaning. As Sherri Irvin argues:

The 1960s saw the genesis of an artistic trend that seemed to give substance to the theories of Foucault and Barthes. The appropriation artists, beginning with Elaine Sturtevant, simply created copies of works by other artists, with little or no manipulation or alteration, and presented these copies as their own works. The work of the appropriation artists, which continues into the present, might well be thought to support the idea that the author is dead: in taking freely from the works of other artists, they seem to ask, with Foucault, “What difference does it make who is speaking?” (123-124)

Yet such dismissals of originality and authorship proved unconvincing outside of academic cultures. While the barrage of comments levelled against Prince and other appropriation artists have not made any meaningful impact on copyright laws, the comments are useful as they suggest that virtues of authorship and originality still hold sway in contemporary society, the growing use of digital technologies notwithstanding. Warhol’s works can, in fact, be seen as original insofar as they depart from their source in a predictable yet distinctly Warholian manner, transforming well-known images into commodities in ways that hadn’t, in fact, been seen before. They epitomize Gilles Deleuze’s concept of “difference within repetition” (24), relying on the aesthetics of mass production while offering something specific from the artist. Warhol’s work stands, as Mario Perniola argues, on the precipice between Modernism and Postmodernism, effectively destabilizing conceptions not only of art, but of its other: advertisement, celebrity, etc. As Perniola writes, the point of departure for Warhol’s works “is the image of modern information such as we find in newspapers, television, or advertisement” (27). Warhol’s art showed not only that art could be a commodity, but that the commodity could be a work of art. If anything, Warhol’s work reinforces his admiration for the original star or image of modernist poetics, the potency of their meaning, even if Warhol is seeking to undo it. Contemporary rephotography lacks such ideological underpinnings.

Prince was more recently the subject of another particularly scathing piece in The New Yorker by Schjeldahl in 2014. Schjeldahl concedes that while Prince’s work is art, it is “by a well-worn Warholian formula” (“Richard Prince’s Instagrams”). He also writes: “Possible cogent responses to the show include naughty delight and sincere abhorrence. My own was something like a wish to be dead – which, say what you want about it, is the surest defence against assaults of postmodernist attitude.”

Postmodern sensibility has notably waned following 9/11, with the New Sincerity movement seeming to replace it. In his 2012 Atlantic article “Sincerity, Not Irony, is our Age’s Ethos,” Jonathan D. Fitzgerald argues:

Looking back all the way to the 1950s and tracking the trajectory of pop culture, I do see an over-emphasis on irony for sure, but early in the aughts I see a change. Maybe it was September 11, and maybe it was that combined with the pendulum swing of time, but whatever the case, around the turn of the century, something began to shift. Today, vulnerability shows up in pop music where bravado and posturing once ruled.

Fitzgerald notes that since 9/11, postmodern irony has been replaced by values of sincerity and authenticity. But despite the rise in sincerity in popular culture, postmodern attitudes have nonetheless persevered in the context of art, with appropriation art, as Irvin argues, enduring in a contemporary art scene.

The difference between appropriation and plagiarism, appropriation and originality, or inspiration and plagiarism, is difficult at best to distinguish. While Anne Zahalka’s ‘Sunbather’ deliberately replicates—in form and style—Dupain’s “Sunbaker,” its subtle deviations from the original (the switch in gender, the added colour and the red hair) suggest it is more a playful homage than blatant plagiarism. Prince’s work, on the other hand, in its transparent copying of an original, can be considered a form of plagiarism. It does not merely imitate the style of an original, but usurps the thing itself through technological means, moving the original from one medium to another, much in the same way as a photocopier reproduces a copy, rather than producing stylistic differences that closely resemble an original. Analysing “Cowboy,” Higgins notes:

The scene appears as if through a haze, slightly soft and almost indistinct. Prince argues: “I seem to go after images that I don’t quite believe. And, I try to re-present them even more unbelievably.” There is an inevitable loss of detail from photographing the original advert; this becomes more pronounced when the image is enlarged to painting-sized proportions. It acts to distance the image from reality, reminding the viewer that it derived from an advertisement. (59)

Higgins’ comments therefore seem to suggest that a legitimate re-make of an original, as opposed to an exact reproduction, must somehow improve or expand upon the original, or in some way differentiate itself from the original, adding, rather than subtracting from the essence of the image. As Barthes argued in Camera Lucida: “it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there” (55, author’s emphasis). Hence Barthes points to the qualities and context that is already inside an image, noting that we have the capability to add something, while conceding that the image already bares a strong semiotic milieu. This is not to suggest that these photographs have a built-in context, nor does it mean that photographs can simply mean anything we want them to, only that their context is malleable to the certain historical, political, and social blueprints we attach to them.

While plagiarism is not at all new in a contemporary digital context, social media has arguably allowed greater accessibility to the works of others, further enabling creative borrowing of users’ works, blurring the lines between what is acceptable and what is unlawful. For Kembrew McLeod and Peter DiCola, copyright can actually act as a “constraint to creativity” (11). Discussing the use of sampling in the hip-hop industry, they note in a similar manner to Boon that such artists have forced us to rethink what constitutes creativity in a digital world (5). They furthermore argue that websites such as Youtube have “altered our relationship with technology and cultural production by providing consumers with the tools to become producers.” The transition from consumers to “prosumers” (Toffler 11) is also present in Instagram, where everyday consumers can produce their own photographic content without much corporate intervention.

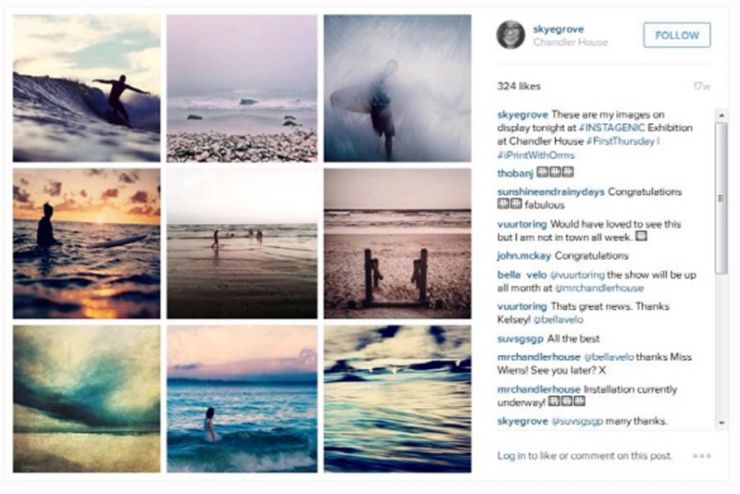

Yet while Prince has managed to undertake his artwork with relative legal ease, even profiting from appropriation in a more digital environment, other users have been caught copying and editing other Instagram users’ work while claiming ownership of the photographs. One such case is that of Skye Grove, one of the celebrity Instagrammers in South Africa who was copying other users’ photos and marketing them as her own on her profile page. Like Prince, Grove not only was reported to have exhibited photos that weren’t her own, but also sold some of the ones she took from other Instagram users. Some of the images that appeared on her page were found to have been photoshopped versions of other photographs, with some images simply flipped horizontally. Following this revelation, Grove was subsequently removed as a judge for the 2015 iPhoneography competition. Reporter Myolisi Sikupela writes that “the scope of Grove posting pictures that are not her own on Instagram and accepting that she took them is expansive,” with Instagram users from Australia to the United Kingdom claiming that their photographs had been copied, edited, and attributed to Grove.

Instagram does have its own privacy policies and copyright laws which it lists on its website. Instagram’s Terms of Use section, under the subtitle “Rights,” clearly states:

You represent and warrant that: (i) you own the Content posted by you on or through the Service or otherwise have the right to grant the rights and licenses set forth in these Terms of Use; (ii) the posting and use of your Content on or through the Service does not violate, misappropriate or infringe on the rights of any third party, including, without limitation, privacy rights, publicity rights, copyrights, trademark and/or other intellectual property rights; (iii) you agree to pay for all royalties, fees, and any other monies owed by reason of Content you post on or through the Service; and (iv) you have the legal right and capacity to enter into these Terms of Use in your jurisdiction.

The page also supports intellectual property rights, yet several users point out that these rights are not routinely enforced. In a 2015 article, Instagram user and photographer Emily Wang discussed the grey areas of copyright policy in Instagram, after another user had copied the pictures from her account and photoshopped them on their own profile page. Wang writes: “I contacted the Instagram team countless times about the problem, but was met with less than helpful responses: ‘Having reviewed your claim, we don’t see how the content you’ve reported, used in the manner depicted, could constitute a violation of your rights.’” While the copied photos were eventually taken down, Wang argues, “All this goes to show that there are still so many grey areas when it comes to intellectual property and ethics.” Discussing Prince’s well-known copying of other people’s photographs, she writes: “Richard Prince’s story reveals a larger problem with social media today: technology is progressing far faster than the pace of policymakers, an especially frustrating phenomenon for those in the artistic or creative fields.”

Indeed, in 2012, Ted Johnson reported on Instagram’s changes to its terms of use, which outlined that: “a business or other entity may pay us to display your username, likeness, photos (along with any other associated metadata), and/or actions you take, in connection with paid or sponsored content or promotions, without any compensation to you” (8). This particular update created an online backlash with both users and entertainment figures expressing concern “that they were giving away ownership rights to their photos” (8). Co-founder Kevin Systrom posted a reply online assuring users that Instagram would remove this claim, yet Johnson notes that “as social-media platforms gain traction, their owners are seeking new ways to monetize content, which has led, from time to time, to an outcry among users concerned about privacy” (8). As Kembrew and DiCola write, “understandably, the owners of copyrighted material are interested in asserting whatever legitimate rights they have regarding how their works are used” (34).

Johnson and others have pointed out the problematic nature of Instagram’s unstable copyright rules, reiterating Abell’s aforementioned comments that the art industries, more than the artists, are to blame for current copyright ambiguity. Intellectual property lawyer Peter Toren, Johnson writes, states that “users who take a photo own the copyright to that image. When they post them to Facebook pages or Instagram accounts, they are essentially agreeing to license them for display on the social-media platform” (8). While many Instagram users have expressed concern and outrage over the manner in which their content may be (mis)used, others have taken the opposite view, arguing in favor of the appropriation artists. Leslie-Jean Thompson writes of the Instagram group Applifam, a global Instagram community that shares and edits content on Instagram. Applifam posts copyright-free images each day, and encourages users and followers to edit them artistically to create what are meant to be entirely new works, after which they select a number of their favorite images (many of which have been featured in exhibitions). Rather than copying entire images and re-posting them as one’s own, Appiflam encourages the view that art is actually made, as previously discussed, through additions and changes to an original to create something new, while still advocating the notion of an artist’s original work and attribution. The interface of Instagram itself, as Spencer Wu notes, is purportedly borrowed from the platform of their social media rival Snapchat. Yet Wu notes that “Instagram took all of the best features from Snapchat and improved them tremendously.” In this way, both Applifam’s and Instagram’s approach to art accords with the views of Boon and McLeod and DiCola, who see sampling as a fundamental act in the process of creativity and producing newness. Yet the difference between sampling to create something new and the act of borrowing without attribution on Instagram remains unclear.

Of Applifam, Thompson writes that in a socially-mediated world, questions of originality and proper use of images are in a constant state of flux. She writes also about the differences between the pre-and post-internet eras and their respective treatments of unaltered images: “Technological advances, however, make it easy for nonprofessional photographers to alter images that would most likely, before the invention of such tools as Adobe Photoshop in 1990, have been left alone by amateurs” (74). As Kembrew and DiCola point out: “the clashes over sampling that occurred in the late 1980s anticipated both today’s remix culture and the legal culture that is largely at odds with it” (5).

In this unstable environment, which simultaneously disseminates and encourages remix culture (Lessig 2008) and original attribution of artists’ work, standardized rules relating to copyright are fluid at best. As Thompson writes: “for the public to photograph [art] work is often difficult: The masters’ works hang in art museums, and the museums rarely allow photographs to be taken. Reproductions of the masterworks, however, are for sale in the gift store” (77). Because of the conflicting messages that exist relating to expectations of copyright, image theft has become increasingly easier since the rules governing the proper use of images have not been properly enforced or solidified. In 2012, for instance, Applifam owner Johan Du Toit posted a forceful message online regarding image use, asking users, in all caps, to respect copyright, which provoked a mixed reaction from Instagram users. Thompson argues that “there was clear confusion from many as to what it actually meant to comply with the basic rule of not using someone else’s work without permission from the artist to do so” (77). While some users feel that the copyright rules hinder creativity in a post-digital environment, others are adamant that they want to retain copyright and ownership over their works, and yet other users are ambivalent—understanding the need for copyright but unsure of where exactly it applies, since so much content online is now seen to be public domain.

The ambiguous status of appropriation in contemporary photography shows that the concepts of plagiarism, originality, and borrowing other artists’ work have undergone reconsideration with the rise of social media. As Tsekeris and Katerelos observe:

[the] nineteenth-century ethos is being fundamentally challenged in the twenty-first century by digital technology. Today, people with access to the internet have unprecedented access to news, information, and commentary, and digital space permits a certain amount of power for ordinary people to determine how free information will be. (20)

This attitude is in stark contrast to those of the early to mid-twentieth century, for whom originality was a given in art. As Lars Lundsten writes, “within emerging media, such as FB or Instagram, derivation becomes an even richer concept than within traditional mass media” (365). Tsekeris and Katerelos similarly note that “for some, particularly those born and raised within the analogue world, sampling is suspect; it represents a form of plagiarism and intellectual property theft” (19).

Early twentieth-century theorists predominantly supported the uniqueness of a work of art, all but denouncing replication and appropriation. In his notable essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), theorist Walter Benjamin argues that mechanical reproduction drastically alters the way in which art is perceived, effectively destroying the aura of authenticity: “That which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art” (221). Yet postmodernists weren’t, and aren’t, overly concerned with authenticity. In their efforts to dismantle claims to authenticity, postmodernists sought to legitimize inauthentic reproduction, celebrating the copy over the original in a strictly Baudrillardian sense. Indeed, for Jean Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation (1981), it is the imitation that supersedes the original. Crimp similarly argues that in its very inauthenticity, Prince’s work gains the aura of art, signifying the ghost of an absence. He states, “Richard Prince steals the most frank and banal of these images, which register, in the context of photography-as-art, as a kind of shock. But ultimately their rather brutal familiarity gives way to strangeness, as an unintended and unwanted dimension of fiction reinvades them” (100). He also notes that “Prince’s rephotographed photographs take on a Hitchcockian dimension: the commodity becomes a clue. It has, we might say, acquired an aura, only now it is a function not of presence but of absence, severed from an origin, from an originator, from authenticity” (100).

Perniola discusses the concept of “art without aura” in Art and Its Shadow (2004). He argues that while Benjamin “relates the disappearance of the aura with the disillusion of the criterion of authenticity with the work of art” (45), the principle of authenticity in contemporary art has “been extraordinarily reinforced” (45). “In fact”, he says, “the more the artistic object is indistinguishable from the utilitarian object, as in the ready-made, the more it has to be certified and guaranteed as unique, unrepeatable and endowed with cultural authority” (45-46). On the other hand, Becker remarks that art depends on its offering of difference: “each work in itself, by virtue of its differences (however small or insignificant) from all other works, thus teaches its audiences something new: a new symbol, a new form, a new mode of presentation” (66). Becker’s comment is useful for understanding the intricacies of art and the problem with appropriation, but less so for the grey area of photographs that rely on altering techniques, such as cropping and flipping. Yet while these techniques alter the original to create something seemingly different, arguably they do not add, but subtract from the original, precisely by removing, rather than adding, artistic elements. Prince does not actually appear to add anything new to the images that he copies, while the Instagram users on the Applifam page are encouraged to alter the images so that they appear to be significantly different. As Higgins’ aforementioned comments attest (and as the artwork on Applifam’s page shows), only our capacity to add something to a photograph distinguishes it from an original, relying on this repetition to produce difference (in a Deleuzian sense), much in the same way Anne Zahalka’s “Sunbather” relies on Max Dupain’s Sunbaker to produce difference. In this way, we can understand Prince’s case, and by extension, the current rise in plagiarism on Instagram, as lacking artistic innovation through the lack of adequate difference. Yet it is not so much the works themselves that lack originality but the methods and intentions of their authors.

Whether a piece of work is art or whether it is permissible are two different points entirely: it has been claimed by many that art and originality are not one and the same, even though a conventional understanding of art is premised on the concept that it cannot be repeated. The grey area of online photography platforms such as Instagram particularly undergird these dilemmas relating to intellectual property and originality, moving beyond the deterioration of the aura in mechanical reproduction to that of the strength of originality in digital replication. In this instance, while certain artists such as Richard Prince have been legally acquitted of wrongdoing, cultural commentary implies that his actions (and the actions of Instagram at large) are an affront to virtues of originality, thereby showing that ideas of plagiarism and originality are malleable to the contexts—legal or cultural—in which they are employed, but no less important to either. While definitions and understandings of what constitutes originality and plagiarism are not clear in either context, what is clear is that originality remains a virtue in the art world, however, contested and elusive.

Works Cited

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: U of Michigan P, 1981. Print.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. Print.

Becker, Howard S. Art Worlds. Berkeley: U of California P, 2008. Print.

Boon, Marcus. In Praise of Copying. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2010. Print.

Christopherson, Richard. “Making Art with Machines: Photography’s Institutional Inadequacies.” Urban Life and Culture 3 (1974): 3-34. Print.

Crimp, Douglas. “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism.” October. 15 (Winter 1980): 91-101. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. London, New York: Continuum, 2004. Print.

Fitzgerald, Jonathan D. “Sincerity, Not Irony, is our Age’s Ethos.” The Atlantic. 20 Nov. 2012. Web. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/11/sincerity-not-irony-is-our-ages-ethos/265466/

Higgins, Jackie. Why it Does Not Have to Be in Focus: Modern Photography Explained. Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2013. Print.

Hu, Yuheng, Lydia Manikonda, and Subbarao Kambhampati. “What We Instagram: A First Analysis of Instagram Photo Content and User Types.” International Conference on Web and Social Media. 2014. Web. http://149.169.27.83/instagram-icwsm.pdf

Irvin, Sherri. “Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art.” British Journal of Aesthetics 45.2 (Apr. 2005): 123-137. Print.

Johnson, Paddy. “Richard Prince Sucks.” Artnet News (21 Oct. 2014). Web. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/richard-prince-sucks-136358

Johnson, Ted. “Instagram Blinks: Outcry highlights copyright conundrum.” Daily Variety (19 Dec. 2012): 8. Print.

Lessig, Lawrence. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. London: Penguin, 2008. Print.

Lundsen, Lars. “Emerging Categories of Media Institutions.” Philosophy of Emerging Media: Understanding, Appreciation, Application. Ed. Juliet Floyd and James E. Katz. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 2016. 361-371. Print.

Marien, Mary Warner. Photography: A Cultural History. London: Lawrence King Publishing, 2006. Print.

McLeod, Kembrew and DiCola, Peter. Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling. Durham: Duke UP, 2011. Print.

Perniola, Mario. Art and Its Shadow. London: Continuum, 2004. Print.

Potts, John and Andrew Murphie. Culture and Technology. New York: Palgrave, 2003. Print.

Rowe, Hayley. “Appropriation in Contemporary Art.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 3.6 (2011). Web. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/546/appropriation-in-contemporary-art

Samuels, Liron. “How Richard Prince Sells Other People’s Instagram Photos for $100,000.” DIY Photography. 21 May 2015. Web. http://www.diyphotography.net/how-richard-prince-sells-other-peoples-instagram-photos-for-100000/

Samuels, Liron. “Photographer Sam Abell Talks About “Cheeky” Richard Prince After Prince Sold his Photo for Millions.” DIY Photography. 29 May 2015. Web. http://www.diyphotography.net/photographer-sam-abell-talks-about-cheeky-richard-prince-after-prince-sold-his-photo-for-millions/

Schjeldahl, Peter. “The Joker: Richard Prince at the Guggenheim.” The New Yorker. 15 Oct. 2007. Web. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/15/the-joker-2

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Richard Prince’s Instagrams.” The New Yorker. 30 Sept. 2014. Web. http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/richard-princes-instagrams

Sikupela, Myolisi. “Top South African Instagrammer accused of plagiarism, fraud.” Memburn. 6 Sept. 2015. Web. http://memeburn.com/2015/09/top-south-african-instagrammer-accused-of-plagiarism/

SpinOne. “The Richest Photographer in the World.” Digital Photography Review. 9 Dec. 2015. Web. http://www.dpreview.com/forums/post/56977965

“Terms of Use.” Instagram Help Center – Privacy and Safety Center. Instagram. 19 Jan. 2013. Web. https://help.instagram.com/478745558852511

Thompson, Leslie-Jean. “The Photo Is Live at Applifam: An Instagram Community Grapples With How Images Should Be Used.” Visual Communication Quarterly 21.2 (2014): 72-82. Web.

Toffler, Alvin. The Third Wave. New York: Bantam Books, 1981. Print

Tsekeris, Charalambos and Katerelos, Ioannis. “Web 2.0, complex networks and social dynamics.” The Social Dynamics of Web 2.0: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Eds. Charalambos Tsekeris,and Ioannis Katerelos. New York: Routledge, 2014. 1-14. Print.

Wang, Emily. “Instagram is full of copyright loopholes—it made my career, but it could break yours.” Quartz. 11 June 2015. Web. http://qz.com/424885/i-got-a-job-posting-photos-of-my-dog-on-instagram-but-others-arent-so-lucky/

Wu, Spencer. “Two Sides to a Story: Instagram Creates Culture of ‘Sampling’ Other Social Media Platforms.” The Bottom Line. 14 Aug. 2016. Web. https://thebottomline.as.ucsb.edu/2016/08/two-sides-to-a-story-instagram-creates-culture-of-sampling-other-social-media-platforms