5.7 American Regionalism

Works Progress Administration and the New Deal

(https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history) Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1941 – Chapter Edited by Jennifer Lorraine Fraser to support the history of art and architecture.

Read the Original Chapter Outline by following these links

The election of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signaled both immediate relief for the American public against the catastrophic effects of the Great Depression, as well as a permanent shift in the role of the federal government in guiding the economy and providing direct assistance to the people, albeit through expensive programs that made extensive budget deficits commonplace. For many, the immediate relief was, at a minimum, psychological: Herbert Hoover was gone, and the situation could not grow worse under Roosevelt. But as his New Deal unfolded, Americans learned more about the fundamental changes their new president brought with him to the Oval Office. In the span of little more than one hundred days, the country witnessed a wave of legislation never seen before or since.

Roosevelt understood the need to “save the patient,” to borrow a medical phrase he often employed, as well as to “cure the ill.” This meant both creating jobs, through such programs as the Works Progress Administration, which provided employment to over eight million Americans (Figure 26.1), as well as reconfiguring the structure of the American economy. In pursuit of these two goals, Americans re-elected Roosevelt for three additional terms in the White House and became full partners in the reshaping of their country.

While much of the legislation of the first hundred days focused on immediate relief and job creation through federal programs, Roosevelt was committed to addressing the underlying problems inherent in the American economy. In his efforts to do so, he created two of the most significant pieces of New Deal legislation: the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) and the National Industry Recovery Act (NIRA).

The NIRA created the Public Works Administration (PWA). The PWA set aside $3.3 billion to build public projects such as highways, federal buildings, and military bases. Although this program suffered from political squabbles over appropriations for projects in various congressional districts, as well as significant underfunding of public housing projects, it ultimately offered some of the most lasting benefits of the NIRA. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes ran the program, which completed over thirty-four thousand projects, including the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel in New York. Between 1933 and 1939, the PWA accounted for the construction of over one-third of all new hospitals and 70 percent of all new public schools in the country.

President Roosevelt’s Federal Project Number One allowed thousands of artists to create public art. This initiative was a response to the Great Depression as part of the Works Project Administration, and much of the public art in cities today date from this era. Although Roosevelt’s relief efforts provided jobs to many and benefitted communities with the construction of several essential building projects, the violence that erupted amid clashes between organized labor and factories backed by police and the authorities exposed a fundamental flaw in the president’s approach. Immediate relief did not address long-existing, inherent class inequities that left workers exposed to poor working conditions, low wages, long hours, and little protection. For many workers, life on the job was not much better than life as an unemployed American. Employment programs may have put men back to work and provided much-needed relief, but the fundamental flaws in the system required additional attention—attention that Roosevelt was unable to pay in the early days of the New Deal. Critics were plentiful, and the president would be forced to address them in the years ahead.

Click and EXPLORE

An online exhibition of works created under the WPA curated by the Brooklyn College

American Regionalism (https://boisestate.pressbooks.pub/arthistory/chapter/modernism-america/)

In 1929 the economic boom ended with the crash of the stock market and the Great Depression began which would continue for over a decade. During the 1930s in the Plains states it was exacerbated by the Dust Bowl, a drought that created devastating dust storms eroding much of the topsoil and causing many families to lose their farms. Migrant Mother: Nipomo, CA by photographer Dorothea Lange is the record of one such family.

In cities, bread lines and soup kitchens were crowded and artists like Raphael Soyer documented that reality for the WPA Federal Arts Project. The WPA provided work for artists of all backgrounds and ethnicities. Erika Doss records that a 1935 survey showed that 41 % of WPA artists were female and most were working class.4

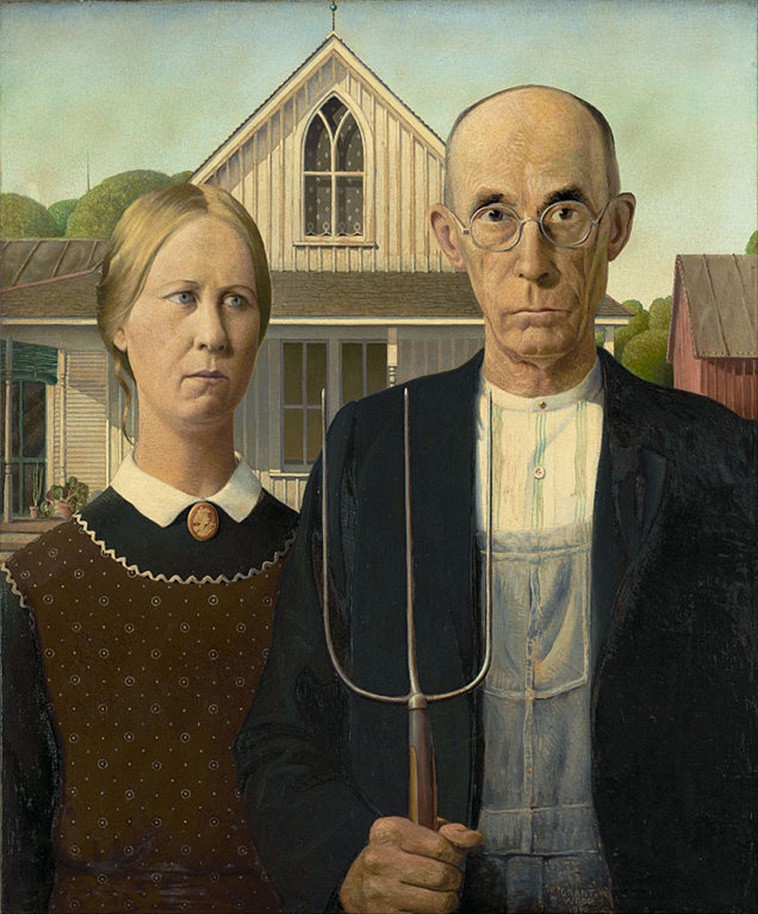

But these gritty images were not the most popular style of art at that time. A number of artists from rural states were making paintings that gave a heroic and positive image of the American Heartland. Thomas Hart Benton from Missouri, Grant Wood from Iowa, and John Steuart Curry from Kansas were the best-known of this “Regionalist” movement. None of these men were unsophisticated; all had an awareness of the modern styles, abstraction, and they brought that sensibility to their images of stoic, strong American figures. Benton would go on to teach a young painter from Cody, Wyoming, named Jackson Pollock at the Art Students League in New York. Regionalism was in line with the democratic ideals of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, although there is also a nationalistic quality to the stereotypical figures pictured by these artists. The extremity that the country found itself in required a more positive, hopeful art that found its expression in Regionalism.

Additional Resources:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/wood-grant/life-and-legacy/

https://www.lib.iastate.edu/about-library/art/grant-wood-murals/home-economics-panel

https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/dorothea-lange-migrant-mother-nipomo-california-1936/