4 LinkedIn Learning as Professional Development

Educator as Learner

Jennifer Rouse Barbeau

Abstract

Teaching adults full-time while simultaneously keeping hands-on skills current in complex, fast-moving fields is a real challenge faced by many college professors. In May 2018, I planned, requested, and completed four days of professional development (PD) training using seven LinkedIn Learning technology-focused video courses, totaling over 31 hours of video viewing. The experience was both humbling and productive. Despite working full days, I completed 58% or less of each of four selected LinkedIn Learning courses over four days, abandoning three courses altogether and adding one course impulsively on Day Two. My poor completion rates were predictable given my failure to plan for scaffolding my own learning. I completed only 21% of my original goal. Was my ambitious target setting evidence of professorial arrogance, the assumption that I could learn more efficiently than my students? I was surprised by the strategies that helped keep me on task, and encouraged to see that my retention rates have been high.

Ultimately, I found LinkedIn Learning to be an efficient way to revisit and confirm industry-specific approaches, strategies, and current trends sufficiently to bring that learning to classroom teaching in industry-specific courses. This PD practice made me a better, more realistic teacher to my present and future students. Lessons learned? Request four to five times the total video-viewing hours as total PD time, or conversely, select videos to fill only 20% to 25% of the total PD time. For example, in a five-day PD window, plan for a maximum of eight to 10 hours of video viewing time, with the balance of the 40 PD hours protected for note-taking and hands-on software practice.

Key Words

asynchronous, autoethnography, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, chunking, Cornell notes, intrapersonal intelligence, professional development

Background

Before becoming a teacher, I studied illustration and advertising, then worked as a graphic designer and art director, and ultimately added journalism and short story and novel writing to the mix. More than 20 years ago, I responded to a call by a college for continuing education courses and teachers, and for several years shared my love of interior design with students taking general interest night courses. Eventually I moved into a marketing position in the college system, and then, when a full-time teaching position in Advertising and Marketing Communications came up at a nearby college, I took the plunge and became a full-time college professor.

Full-time teachers in the college system work up to 44 scheduled hours per week during the academic year, a total that includes teaching-contact time (hours in the classroom), preparation and marking time, and general administration time. This means the work week is very full. I have found it daunting to keep up with design technology and social media marketing trends in addition to these 44 hours per week; by necessity, academic requirements, advising students, and program coordination take priority. Although I teach a wide variety of software-specific courses only once per semester, it is important that I keep my skills current by exploring software and industry-specific platforms. Luckily, our contract gives full-time professors 10 days of professional development (PD) per academic year. I have attended design-related conferences with the support of my college’s PD funds, but I have found it challenging to find targeted PD that includes time for hands-on exploration of design software. It is important to me to identify PD that fits into the annual faculty 10-day window, and also supports skill building for several technology-based courses. But more often than not, I was reading textbooks on Adobe Creative Suite, Microsoft Project, social media strategies, and media buying on my own time, instead of requesting more formal PD for software skill building. Textbook reading seemed too flimsy a resource to submit as a PD request. And so my practice sessions took place infrequently, for brief stints and without formal scheduling. This approach interfered with a healthy work/life balance and also left me feeling that I needed more time with the tech tools that are so important to the fields I am preparing students to enter.

Introduction

When LinkedIn Learning became available to every college faculty member, student, and staff member, we were encouraged to use it. A quick look through the LinkedIn Learning library confirmed that many resources existed to provide the software immersion time I craved. Still, I had two questions about LinkedIn Learning’s place in my professional development.

Research Questions

- Would time with LinkedIn Learning video courses be recognized by my college as credible PD?

- To what degree could LinkedIn Learning support my professional development in design, project management, and digital marketing management, within a compressed timeframe (that is, the maximum window of five consecutive days allowed by our faculty collective agreement)?

Teaching and Learning Objectives

- Identify current, high-quality, industry-specific skill development training at no cost

- Schedule up to five consecutive workdays devoted to PD to meet the requirements of my collective agreement, namely that of discussion with and approval by my associate dean

- Revisit, explore, confirm, and develop industry-specific skills required for the ongoing teaching of industry-specific courses

- Explore current trends and tools in a compressed timeframe

Method: Autoethnography

I conducted informal qualitative research, acting as research author and sole active research participant. I used self-reflection and writing to explore my personal PD experience using LinkedIn Learning video-based training, and to connect it to a wider professional, personal, and cultural workplace context.

Procedure

On March 22, 2018, I signed up for LinkedIn Learning in order to search the LinkedIn Learning library for appropriate courses for a PD request. I uncovered several excellent choices and made a list of courses that, when combined, covered four workdays. (Note that the 2017-18 school year was a strike year in which only nine PD days were allowed.)

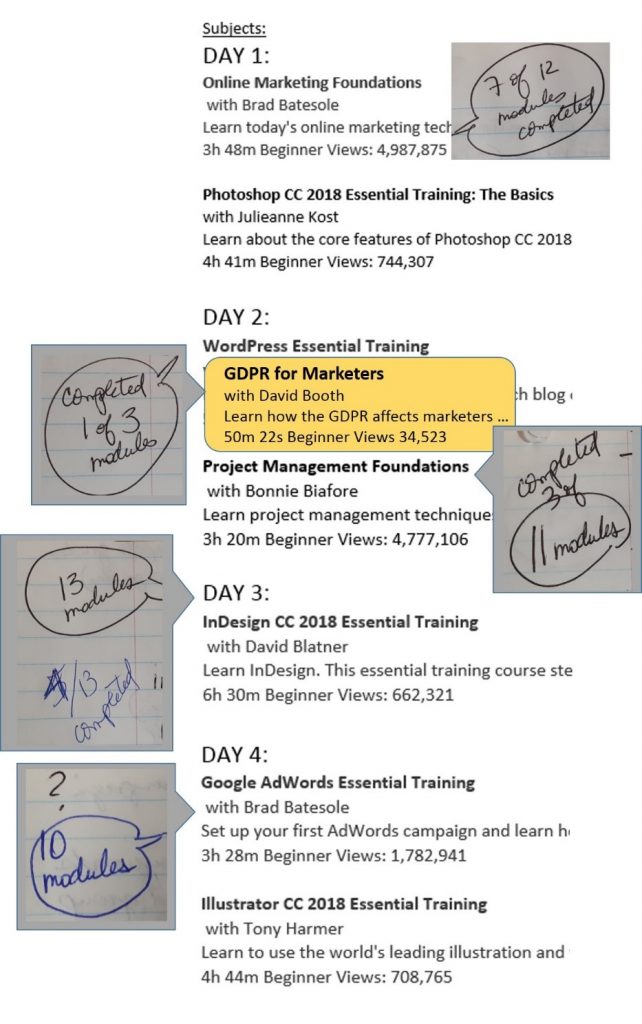

I sent an email request to my associate dean on Tuesday, May 8, 2018 at 4:38 p.m., asking for four days of professional development for the 2017–18 academic year, to take place in the non-teaching period from Tuesday, May 22 to Friday, May 25, 2018, off campus (at my home). A Professional Development Authorization form in PDF, showing no related costs, was attached to my request, along with a detailed list of the seven LinkedIn Learning courses I planned to complete (see Figure 4.1). The email also included a list of the five days of training I had already completed in 2017—18.

As part of my professional development for the 2017-18 academic year, I am requesting the following:

- 4 days to complete LinkedIn Learning training (31 hrs 18 min)

- Tuesday, May 22, 2018 to Friday, May 25, 2018

- Off campus (at my home)

Subjects:

Day 1:

Online Marketing Foundations with Brad Batesole

Learn today’s online marketing techniques and find out how to build a successful online marketing campaign for all digital…

3h 48m Beginner Views: 4,987,875

Photoshop CC 2018 Essential Training: The Basics with Julieanne Kost

Learn about the core features of Photoshop CC 2018, from interface basics to key concepts that all Photoshop users should know, regardless of how they use the program.

4h 41m Beginner Views: 744,307

DAY 2:

WordPress Essential Training with Morten Rand-Hendriksen

Learn how to create your own feature-rich blog or website with WordPress. Find out how to schedule posts, customize themes…

5h 27m Beginner Views: 5,805,122

Project Management Foundations with Bonnie Biafore

Learn project management techniques to effectively manage simple projects and complex enterprise-wide initiatives. This course…

3h 20m Beginner Views: 4,777,106

DAY 3:

InDesign CC 2018 Essential Training with David Blatner

Learn InDesign. This essential training course steps you through the world’s premiere page layout app, Adobe InDesign.

6h 30m Beginner Views: 662,321

DAY 4:

Google AdWords Essential Training with Brad Batesole

Set up your first AdWords campaign and learn how to get more visitors to your website and more value from your PPC spend.

3h 28m Beginner Views: 1,782,941

Illustrator CC 2018 Essential Training with Tony Harmer

Learn to use the world’s leading illustration and vector drawing application — Adobe Illustrator — to create artwork for print, for the web, or for use in other applications.

4h 44m Beginner Views: 708,765

Figure 4.1, Pedagogical Development Agenda: The email I sent to my associate dean on May 8, 2018 acted both as support for my PD request, and as a self-proposed agenda for my four continuous days of study.

Approval by my associate dean was received by email on Wednesday, May 9, 2018 at 5:28 p.m. I began LinkedIn Learning training on Tuesday, May 22, 2018 on my work laptop at home so that I would have access to current Microsoft Project and Adobe Creative Suite software. I kept handwritten notes. Handwritten notes allowed me to regroup information as I listened to the audio portion, enabling me to toggle my attention between the video visuals (including the running text) and my own, tactile visuals.

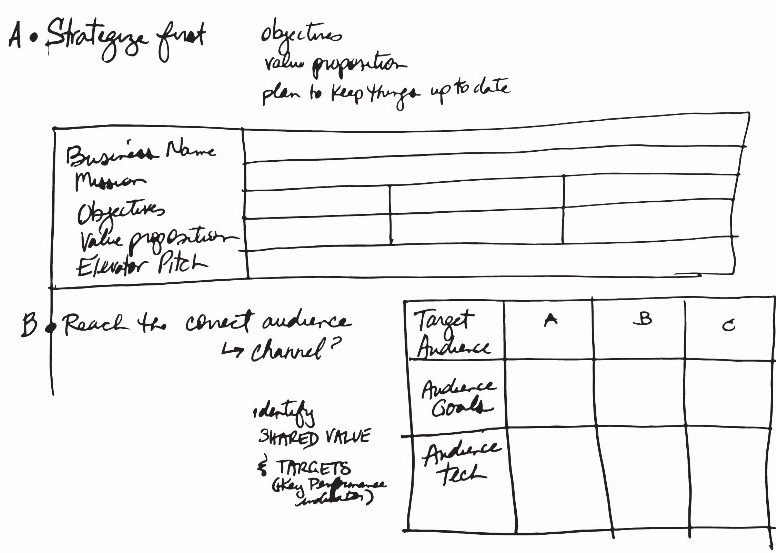

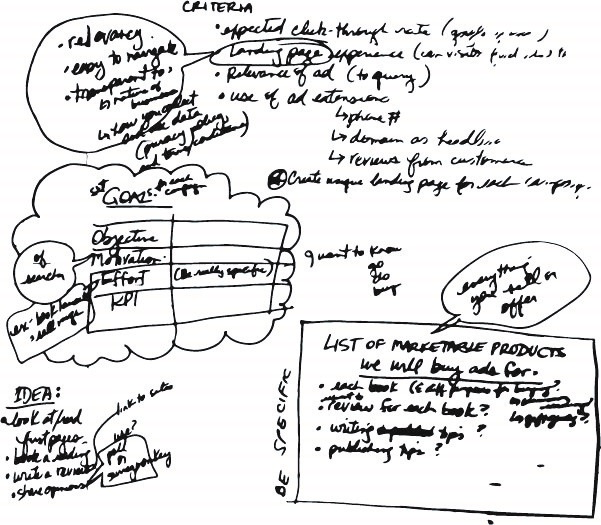

Speech bubbles, cloud shapes, squares, and lists with a variety of formatting and levels were tools used to “chunk” information visually; notice how key points are written in the far left margin, while general notes take up a wider right-hand column, with a summary block at the bottom of the page.

The 16 pages of notes I made used a variety of visual formats that were instinctive and not unlike Cornell notes (Gonzalez, 2018; Donohoo, 2010), a visually organized note-based summarizing technique I did not know at the time my PD took place. A typical Cornell notes approach divides a note-taking page into three parts, with key points placed in a narrow column on the left, general notes filling a wider right-hand column, and a summary of the topic set along the bottom.

I worked eight hours or more per day on the selected LinkedIn Learning courses. My learning process was fourfold:

- I watched the videos;

- I listened to the videos;

- I read along with the text as it was highlighted;

- I created 16 pages of handwritten notes to highlight key concepts, using various shapes and organizational levels to simplify and regroup information.

A fifth process happened simultaneously: I fidgeted tremendously in my chair, standing, sitting, lifting my legs onto the chair, kneeling on the chair, leaning on the desk, crouching with my feet on the seat of the chair, and so on. I was aware of my inability to “settle down.”

Research into the impact of sedentary leisure activity (screen or non-screen time, sitting) on working memory and academic performance suggests that 10- to-20-minute breaks from activity on weekdays seem to bolster academic performance overall, while longer weekend breaks actually seem to impede working memory (Féliz Nóbrega, 2017). Physical activity in general is a contributor to cognitive development, including working memory and brain maturation in children, even those with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) diagnoses (López Vicente, 2016). Doing (also labelled experiential learning) improves performance on delayed tests, especially when doing includes judging and selecting activities (Kaneko, Saito, Nohara, Kudo, & Yamada, 2018).

That said, there is evidence that brief rests during workdays, as well as physical activity (in general and while learning), support the retention of concepts. In retrospect, I speculate that my fidgeting provided physical activity that not only allowed me to remember more of what I learned, but also afforded a physical outlet to counterbalance the passive activity of video watching. As a result, my energy levels stayed high throughout these eight-hour periods of intense mental activity. In the words of Llinas (2001, as quoted in Lopez Vicente, 2016), “That which we call thinking is the evolutionary internalization of movement.”

Results

My plan was overly ambitious. I had scheduled four 8-hour days to complete a total of 31 hours, 18 minutes of course viewing (97.8% of my allotted PD time). I spontaneously added an eighth course on Day Two, increasing the total LinkedIn Learning running time to 32 hours, 48 minutes, or 102.5% of my allotted PD time. I hadn’t factored in time for trial of the software as I worked through the lessons, nor had I considered time for reflection and exploration to consolidate learning.

Though I worked for eight hours or more each PD day, I completed between 27% to 58% of each LinkedIn Learning course I viewed. By the middle of Day One it became evident I could not complete the full range of courses within my anticipated timeframe. Ultimately, I worked on only four of the original selected courses, abandoning the exploration of three courses altogether. I added one extra course on Day Two, but short as the course was at 50 minutes, 22 seconds, I completed only one-third of it.

My notes (Figure 4.5 ) reflected completion rates for each course I tackled, with the exception of the final Day 4 efforts, during which I took six pages of notes, but did not record how many modules I was able to complete in the day’s eight-hour timeframe. A subsequent check of my notes against content confirms that I completed four of 10 modules. The coloured block indicates an outlier course that was added on impulse on Day Two.

Pedagogical Considerations: Learning Theories in Practice

Compared to other forms of PD, such as attending a conference or completing a traditional multi-week course, using the LinkedIn Learning video library as PD content provided more opportunity for deliberate reflection, before, during, and after the specified PD timeframe.

A key challenge for me as an educator is to anticipate and scaffold learning for a wide range of students. In selecting autonomous learning via LinkedIn Learning for my own PD, I failed to plan for scaffolding my own learning. The resulting outcomes — abysmal completion rates, abandoned courses, and bruised self-esteem — instigated reflection upon my own learning and, more positively, informed my understanding of the student experience. My struggle allowed me, as an educator, to explore the question of how I (and similar others) could and would learn. This process also allowed me to identify barriers to my own learning and ultimately to my own teaching. Had I simply been too ambitious in my targets? Could my low completion rates be equated with low persistence, even though I had invested the allotted eight hours per day? How often had similar ambitions and presumptions by me, the teacher, led to demonstrations of what looked like low persistence in my students, and, if that were true, how fair an assessment was it to assume that low completion rates meant a lack of time invested?

My initial goal was to integrate additional knowledge with my existing knowledge, efficiently, over a constrained time period. That strategy seemed simple: expose myself to mastery-level teachers to whom I had access via video, and so also enjoy the luxury of rewinds and side explorations while I worked in the comfort of my own home. Paradoxically, I did not factor in time for those rewinds or explorations. In practice, my PD involved more than the exposure-only learning I had planned; it also forced me to consider what autonomous learning looks like, at least for me, an experienced student who earned a Master of Education degree as recently as 2016. And so I engaged in meta-learning: LinkedIn Learning learning and also participatory learning about learning.

Key questions arose as I worked. Was it realistic to self-assign more than eight hours daily of video viewing? How much watching is learning? Is passive learning enough? What tactics could scaffold my own learning? How much time was really needed?

Right from the start, the process of reviewing and selecting video courses to fill an intensive four-day period of concentrated professional development allowed me to reflect on my goals and make decisions about the scope of learning I would tackle. It is interesting to me that I ultimately chose to revisit subjects with which I was already quite practised. Not unlike post-secondary students, I chose to add to my existing knowledge rather than tackle areas where I might have perceived a greater gap between what I knew and what I would need to know (Lenarcic Biss & Pichette, 2019). It is also interesting that I set such ambitious targets. As an educator with more than a quarter-century of experience, did I truly expect to simply soak up learning without doing or reflecting?

Time itself was a player. As I worked, I was essentially under the tutelage of experts who were nonetheless unavailable to me except in their asynchronous form. We could not discuss; I could not ask questions. There was no time for me to process a concept, and no opportunity to reflect it back in words or demonstration to instigate feedback or clarification from the teacher, the video expert. The work day began and ended at essentially the same time it would have had I been on campus, and yet the days both sped and crawled. I became acutely aware of the clock, abandoning a given video course well before the end of its running time in order to keep to my original eight-hours-per-day schedule. I felt my progress criticized by time. After all, I knew these subjects already, well enough to teach them. Why was I completing well below 50% of each course I viewed?

Still, I was learning. My note-taking was my best confirmation of this, providing the richest evidence that I was “connecting the dots.” The video courses each sparked a renewed enthusiasm for the tools explored; I found myself wanting to investigate my self-created software exercises more fully, and used discipline to reluctantly return to the videos to continue learning. I was both distracted student and diligent teacher, toggling between the two roles to inch forward in my agenda.

Had a video been taken of my learning-by-video, it would have shown a very restless student indeed. I moved from sitting to standing to squatting on the chair, to stretching, to leaning. My fidgeting “workspace” extended in a semi-circle around the computer screen where the video played. Between courses, I moved the laptop from my desk to my dining table to a nearby sofa and so on, physically moving almost non-stop within a three- or-four foot range from the screen. Had I been a student in one of my classes, I would have driven myself to distraction! It is important to note that I do not suffer from any attention disorders, and in fact am capable of working for extended periods of time without a lot of movement (despite knowing that it is not a good thing for my physical health). I regularly watch movies without the need to move to this degree. And so why the fidgeting? My best speculation, on reflection, is that the constant movement provided a vehicle for my rising energy as I got excited about concepts but was nonetheless “trapped” in the passive experience of watching, rather than doing. I could not express myself verbally and have a teacher or classmate answer, and so discourse provided no relief. My best option was to move as a way of maintaining a high level of concentration.

Another possible analogy comes from my early teen years, when it was common cultural practice to spend literally hours speaking to one friend or another on a telephone landline, firmly tethered to a wall. Those hours were spent in similar fidgeting — lying on the floor, legs up on a wall, crouching, and pacing. Again, this was a period of concentrated focus on auditory-only information, while restrained in a limited space around the landline anchor point — not unlike the limited viewing range around my laptop.

Did I adjust my learning after I noticed I couldn’t sit still? Yes, and no. What I did was position my laptop to ensure I had room to move. Did my restlessness prompt me to change my scaffolding tools? I made sure I had pen and paper to take notes, which channelled my physical energy. As an artist, I had many coloured pens and other writing or drawing instruments and surfaces nearby, but instead I stuck with lined foolscap paper and a blue or black pen. Why? Because I was conscious of the time, and of the workplace context of my efforts, even though they took place in my own home. It seemed important to impose a workplace-like discipline on my studies to keep me on task. Was this a leftover from my own school years? Yes, but I allowed myself the room to move around, which I would not have done (or been allowed to do) in the physical classrooms where I learned as a child and young adult.

Nor did I fidget when I worked on online courses — in this same space and home — when I completed my M.Ed. At those times, I was engaged in such concentrated mental and keyboard activity that I had to maintain a seated position in order to work. Interestingly, in both my childhood classrooms and in the online M.Ed. environment, I was aware of real others sharing the experience with me. It was the presence of real-time others that settled me, perhaps for social and cultural reasons. Was this new fidgeting an adaptation that was part of my learning journey? Definitely. I learned I could use movement as a self-regulating strategy to encourage persistence. I moved globally to stay on task.

Other tactics I had used to scaffold my learning — note-taking, reading along with the video, and practising with the related software during viewing breaks — were deliberate (although not planned in my initial agenda). This other perpetual movement was involuntary. I would have felt quite foolish had I been in a crowd. Perhaps the isolation of working in my otherwise empty home gave me “permission” to use this particular scaffold.

This video-based PD experience created overlapping paradigms of learning, using several forms of learning in action:

- Experiential Learning: LinkedIn Learning allows workplace-simulation using industry-specific software.

- Adult Learning: I felt the urgency of immediate use for teaching my related courses.

- Self-directed Learning: LinkedIn Learning provides a robust library of PD options.

- Cognitive Apprenticeship: I was aware that I took on the role of apprentice to someone who had mastered a skill they were sharing via video, asynchronously.

- Situated Learning: My workplace laptop and the software loaded within it formed part of the learning context, which was portable to my personal living environment; nonetheless, that laptop-based “internal” software world provided its own distinct physical environment. I moved from the LinkedIn Learning video course to the software-specific context, all while inhabiting the safe and flexible home environment, thereby experiencing three worlds at once.

- Cognitive Information Processing: A challenge in this form of PD for me was processing the information received via video, translating that to handwritten notes (a familiar learning strategy that has worked well, historically, for me), attempting the skills physically in the software space, and then returning to consume more video-based learning.

- Multiple Intelligences: Despite some skepticism about the validity of this learning construct (Jensen, 2000), I had the sense that my learning process required the use of two forms of intelligence, specifically:

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, or the capacity to solve problems through mastering my hand-eye coordination and moving globally; paradoxically, while kinesthetic intelligence has been correlated with an inability to focus (Sener & Çokçalıskan, 2018, p. 126, par. 3, item 3), my sense was that movement was a result of my need to focus; and

- Intrapersonal intelligence, or the capacity to understand myself and my learning needs.

Conclusions

As I look over my notes many months later, I speculate that I have retained approximately 90% of what I learned. Ultimately, the combination of video course viewing, handwritten note-taking, active trial and exploration of the related software, and subsequent review of my handwritten notes periodically in the weeks and months afterward were successful in increasing my knowledge about a wide range of technology-based subjects in a very compressed period of four days. However, video course completion rates were low, and three courses were never explored at all. Despite the benefits and significant learning that resulted from this PD, I left the process somewhat shocked and embarrassed by my performance.

My first research question was: Would time with LinkedIn Learning video courses be recognized by my college as credible PD? My request was received and approved without question or concern, implying that my college did indeed find video course viewing to be credible PD. One surprise for me was that I packed every requested PD moment with video-viewing time, and therefore did not allow for or acknowledge the practice or reflection time I knew as an educator would be required for me to learn and retain the material. What this approach reveals is doubt on my part that video viewing would be credible PD. I stacked up the viewing time because I felt that doing less would be, or would be seen as, insufficient effort. That is a humbling realization. I could choose any number of adjectives to describe my mindset at the outset of this PD: arrogant, superior (to my student learners), timid, naïve, apologetic. Regardless of the nuance in why I chose not to recognize my own need for learning scaffolds, the truth is that I failed to build in learning time and instead put the full burden of my professional development over those four days wholly on the passive exercise of video viewing. In practice, video viewing was not enough.

A second research question was: To what degree could LinkedIn Learning support my professional development in design, project management, and digital marketing management within a compressed timeframe? The answer to this is more complex. I completed 27% to 58% of five (out of eight) LinkedIn Learning courses, totaling 32 hours, 48 minutes combined, in a PD working period of four 8-hour working days, or 32 hours. My feeling is that I retained approximately 90% of what I learned, noting that those retention rates are based on a subsequent review (and reflection) some six months later of the handwritten notes taken during the video learning. To summarize in numbers the degree of support for PD in design, project management, and digital marketing management, I estimate:

- 32 hours of PD time completed;

- 31 hours, 18 minutes of video viewing planned for those 32 hours (97.8% of full PD time) became a combined 32 hours, 48 minutes of video running time (or 102.5% of my full PD time) when I spontaneously added a course on Day Two;

- 21% of total video running time was actually viewed (6 hours, 48 minutes);

- 21% of my PD time was therefore spent watching videos and fidgeting; the remaining 25 hours, 12 minutes (79% of my PD time) was spent taking notes and practicing software tasks;

- 16 pages of hand-written notes produced, or one page for every 25 minutes of video viewing time;

- Estimated 90% retention rate via review of notes.

Metrics

| Day | Course | # Modules | % Completed | # Pages of notes | Daily total of notes | Hours per course | % of courses viewed |

| 1 | Online Marketing | 12 | 58 | 5 | 5 | 3h48 | 58% |

| Photoshop | 15 | 0 | 0 | 4h41 | |||

| 2 | WordPress | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5h27 | 22% |

| GDPR | 3 | 33 | 1 | 0h50 | |||

| Project Management | 11 | 27 | 1 | 3h20 | |||

| 3 | In design | 13 | 31 | 3 | 3 | 6h30 | 31% |

| 4 | Google Ad Words | 10 | 40 | 6 | 6 | 3h28 | 40% |

| Illustrator | 15 | 0 | 0 | 4h44 | |||

| 4 days | 8 courses | 93 total modules | 24% of modules actually completed | 16 pages completed | 4 note pages per day on average | 32.8 total course hours | 21% of courses actually viewed |

- I accomplished 24% of my original goal.

- 21% of PD time was devoted to video viewing.

- 79% of PD time was devoted to note-taking and hands-on practice.

- Although I have no metric to validate my estimate, I believe note-taking time was pivotal in supporting retention over time.

Organizing the data for comparison illustrates how poor my completion rates were: 19 of 93 modules were completed (or 24%), with only 21% of course running time viewed. Interestingly, on Days One to Three, I produced roughly one page of notes for every 10% of course viewing time; on Day Four, I created one-and-a-half pages per 10% viewed.Lessons Learned

- LinkedIn Learning is a valid and productive form of self-directed professional development learning; in my case, scaffolding in the form of note-taking and hands-on practice was required.

- Request an additional four to five times the video course hours for PD time. In other words, a three-hour LinkedIn Learning course may require between 12 to 15 hours to complete as PD.

- Reflect a similar addition of exploration hours when assigning LinkedIn Learning training to students.

- Focusing on one area of development (for example, InDesign) per PD period, versus exploring several varied topics, could increase completion rates within a compressed timeframe.

- Using multiple electronic devices (one screen for video viewing and another for practice work) could shorten the overall time requirements by stacking tasks within the same timeframe, although multi-tasking effectively may be a challenge.

Overview of LinkedIn Learning Videos

- Online Marketing Foundations with Brad Batesole (3 hours, 48 minutes)

- Photoshop CC 2018 Essential Training: The Basics with Julieanne Kost (4 hours, 41 minutes)

- WordPress Essential Training with Morten Rand-Hendriksen (5 hours, 27 minutes)

- Project Management Foundations with Bonnie Biafore (3 hours, 20 minutes)

- InDesign CC 2018 Essential Training with David Blatner (6 hours, 30 minutes)

- Google AdWords Essential Training with Brad Batesole (now retired) (3 hours, 28 minutes)

- Illustrator CC 2018 Essential Training with Tony Harmer (4 hours, 44 minutes)

- GDPR for Marketers with David Booth (50 minutes 22 seconds)

List of LinkedIn Learning Videos

Batesole, B. (2018, June 29). Online marketing foundations [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Marketing-tutorials/Online-Marketing-Foundations/693114-2.htmlBatesole, B. (2018, November 21). Google Ads (AdWords) essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Google-AdWords-tutorials/Google-AdWords-Essential-Training-2018/693109-2.html

Biafore, B. (2016, July 10). Project management foundations [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Project-tutorials/Project-Management-Foundations/424947-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a1%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3aProject+Management+Foundations%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2

Blatner, D. (2017, October 27). InDesign CC 2018 essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/InDesign-tutorials/InDesign-CC-2018-Essential-Training/625911-2.htmlBooth, D. (2018, March 16). GDPR for marketers [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Marketing-tutorials/GDPR-Marketers/693115-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a1%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3aGDPR+for+Marketers%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2

Harmer, T. (2018, May 4). Illustrator CC 2018 essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Illustrator-tutorials/Illustrator-CC-2018-Essential-Training/628695-2.html

Kost, J. (2017, October 23). Photoshop CC 2018 essential training: The basics [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Photoshop-tutorials/Photoshop-CC-2018-Essential-Training-Basics/625922-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a1%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3aPhotoshop+CC+2018+Essential+Training%3a+The+Basics+%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2

Rand-Henriksen, M. (2018, June 11). WordPress essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/WordPress-tutorials/WordPress-Essential-Training/372542-2.html

References

Donohoo, J. (2010). Learning how to learn: Cornell notes as an example. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,54(3), 224–227. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40961530

Félez Nóbrega, M. (2017). Patterns of sedentary behavior, physical activity and cognitive outcomes in University young adults: Relationships with academic achievement and working memory capacity. Universitat de Vic – Universitat Central de Catalunya, 2017. Retrieved from TDX Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa (Theses and Dissertations Online) at https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/565727/tesdoc_a2017_felez_mireia_patterns_sedentary.pdf

Gonzalez, J. (2018, September 9). Note-taking: A Research Roundup. Cult of Pedagogy [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/note-taking/

Jensen, E. (2000). Brain-based learning: A reality check. Educational Leadership, 57(7), 76–80. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational_leadership/apr00/vol57/num07/Brain-Based_Learning@_A_Reality_Check.aspx

Kaneko, K., Saito, Y., Nohara, Y., Kudo, E., & Yamada, M. (2018). Does physical activity enhance learning performance?: Learning effectiveness of game-based experiential learning for university library instruction. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(5), 569–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.06.002

Lenarcic Biss, D., & Pichette, J. (2019, January 11) Minding the gap? Ontario postsecondary students’ perceptions on the state of their skills. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.heqco.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/Formatted_%20Student%20Skills%20Survey_FINAL.pdf

López Vicente, M. (2016). Physical activity and neurodevelopment in children. Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 2016. Retrieved from TDX Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa (Theses and Dissertations Online) at https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/585877

Sener, S., & Çokçaliskan, A. (2018). An Investigation between Multiple Intelligences and Learning Styles. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(2), 125–132. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1170867