5 Exemplary Practices for Integrating LinkedIn Learning Video Assets in Online Post-Secondary Courses

Amanda Baker Robinson

Abstract

Based on several semesters of informal experimentation with learning design and observation of real student outcomes, this case study suggests and discusses strategies for leveraging LinkedIn Learning video assets in online post-secondary courses, in order to align with exemplary practices of instructional design and pedagogy. After a survey of relevant pedagogical considerations and instructional design principles, this report advises instructors and instructional designers to deploy a three-phase approach when adding a LinkedIn Learning video to a lesson delivered via a learning management system (LMS).

First, the preparation phase is used to set the stage for learning in a manner that empowers adult learners to approach the video in the ways that they prefer to learn, while having the utilitarian function of helping students use the necessary software and tools effectively. Second, the integration phase simply deals with the effective placement of the video, along with any alternative forms of instruction, in the LMS learning module. Finally, the consolidation phase discusses strategies for making connections between video content and course concepts or real-world practice through self-assessment and application exercises. The importance of motivating students to complete the consolidation tasks is also highlighted.

One case study — the integration of two LinkedIn Learning software tutorial videos in Humber College’s BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing course — is used to illustrate the recommended practices when implementing LinkedIn Learning videos. However, the recommendations made in this report are applicable to any traditional LMS-based, post-secondary teaching and learning environment. These recommendations allow instructors to include videos as a purposeful, well-integrated aspect of the lesson, rather than as outsourced instruction with little to no integration in the LMS materials. Students’ learning experiences are more fruitful when well-designed preparation and consolidation techniques frame the pedagogically sound, video-based lessons provided by LinkedIn Learning .

Key Words

online teaching, online learning, pedagogy, instructional design, universal design for learning, video, video-based instruction, e-learning, adult learners, learning management system (LMS)

Introduction

Based on several semesters of informal experimentation and observation of real student outcomes, this case study suggests and discusses strategies for leveraging LinkedIn Learning video assets in online courses, in order to align with exemplary practices of instructional design and pedagogy. One case study — the integration of two software tutorial videos in Humber College’s BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing course — illustrates the recommended exemplary practices when implementing LinkedIn Learning videos.

Background

Online learning has many well-documented limitations, including the lack of a personal relationship with an instructor, lack of class discussion, and lack of experiential learning. Another reality of online learning is that students with spatial, kinesthetic, and interpersonal intelligences are often at a disadvantage. Finally, learning in an online environment can often be one-size-fits-all, offering few, if any, opportunities for customized learning experiences. As an instructional designer and an instructor at Humber and Canadore Colleges, my goal is to look for ways to compensate for these shortfalls while capitalizing on the flexibility that online learning offers.

Since I hold the dual, and complementary, roles of online instructor of business writing and instructional designer, I have the unique fortune of being able to experiment with new instructional design approaches in my own courses, and then to witness the outcomes firsthand. Business writing can be a dry and unengaging subject, which leads to lower student attention levels, and therefore lower comprehension of, and retention of, key course concepts like writing emails and memos, report-writing, grammar, using Microsoft Word 2016 tools, and more. I have sometimes used my own business writing courses as testing grounds when trying out new tools and approaches if those resources are appropriate for the subject matter. Based on this history of experimentation, I have consistently found that business writing courses that include pedagogically sound video instruction in the teaching of key writing concepts tend to achieve better learning outcomes compared with courses that do not implement video-based instruction. In my personal experience, students consistently report higher engagement with, and higher comprehension levels of, course content when video assets are present.

Based on this informed assumption that video assets do improve outcomes for online learners, I have focused my attention in this case study on recommending ways to deploy LinkedIn Learning video assets within a learning management system (LMS) in order to maximize pedagogical advantages. Humber College has graciously permitted me to share screenshots and content from the BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing online course to support my case study and act as resources for readers. Although I am speaking about my experience teaching business writing at Humber College specifically, and presenting this case study based on these courses, the recommendations made in this report are applicable to any curated, LMS-based online learning experience that deploys videos for the purposes of instructing adult learners.

Pedagogical Considerations

Online learning has many well-documented pedagogical limitations — namely, students with spatial, kinesthetic, and interpersonal intelligences are often at a disadvantage in an e-learning environment. How do instructional designers and instructors compensate for these persistent inequities? Other pedagogical hurdles include how to construct meaningful interpersonal interactions between instructors and students, and from student to student, and how to provide customized learning experiences for a diverse array of learners. Such key pedagogical goals can be achieved — or are more likely to be achieved — with careful instructional design and appropriate implementation of that design. LinkedIn Learning video assets provide an opportunity to leverage several key pedagogies, discussed in turn below, and thereby combat the shortcomings of the online learning environment.

Cognitive Apprenticeship and Situated Learning

Situated learning conceptualizes learning as taking place within a specific context, embedded within a particular social and physical environment. In a traditional post-secondary course, that context is typically a school’s learning management system (LMS), but an LMS can be an abstract, impersonal space. Students are more likely to engage in lessons that have a more personal or practical context, which is why instructional designers often integrate simulations in learning design.

On a related note, cognitive apprenticeship emphasizes the importance of the process in which a master of a skill teaches that skill to an apprentice, thereby creating an interpersonal context for modelling concepts and skills, and achieving situated learning. In Rethinking education in the age of technology, Collins and Halverson (2009) argue:

The pedagogy of the lifelong-learning era is evolving toward reliance on interaction. Sometimes this involves interacting with a rich technological environment such as a computer tutor or a game on the web and sometimes with other people by means of a computer network. The pedagogy of computer tutors echoes the apprenticeship model in setting individualized tasks for learners and offering guidance and feedback as they work. (p. 91)

In a similar way to the computer tutor mentioned in this excerpt, featured narrators in LinkedIn Learning videos take on the role of proven master, a role for which they are exceptionally well qualified. As an example, in the Microsoft Word 2016 tutorial videos that are discussed in the case study later in this paper, content is delivered by David Rivers, a 20-year veteran software trainer. Rivers’ professional focus is on encouraging corporate clients, including Microsoft itself, to integrate technology into their work processes in order to improve efficiency, so his forte is teaching laypeople to use software (Lynda.com, n.d.). As an unrefuted expert, Rivers is an ideal choice for guiding students through training on the Microsoft Word program. There is a clear pedagogical advantage when students can access the expertise of a knowledgeable master, making the case for choosing a LinkedIn Learning video, which uses a rigorous talent selection process, versus braving the sometimes-dubious origins of many open-source videos, or even recruiting a less experienced instructor.

Meanwhile, student viewers become “virtual apprentices” — a stark contrast to reading a text-based lesson, or passively watching a video with no anchoring teacher-figure. Students do perceive a key shift in their own positionality to what is being taught when their learning is situated as a form of cognitive apprenticeship. During a past class, a student compared a Microsoft Word 2016 software tutorial video to “job shadowing,” as if he were watching over the shoulder of a trainer.

It is important to note here that the full benefits of cognitive apprenticeship cannot be leveraged by LinkedIn Learning because videos only communicate one way, from broadcaster to viewer; therefore, there is no teacher responsiveness to individual learners in the form of coaching and scaffolding. However, LinkedIn Learning videos are effective in achieving a one-way sense of cognitive apprenticeship by building students’ sense of trust in the speaker’s expertise. The missing master-to-apprentice communication should be provided in the instructional language that surrounds a video asset and in lesson activities.

Active Reflection

A key aspect of learning is reflecting on the learning experience. In Humber College’s online business writing classes, software tutorials for Microsoft Word 2016 are framed with written instructions that instruct students to open their own software and follow along with the video. Although the videos themselves do not foster reflection per se, instructional design strategies can position a video as a step-by-step guide and thereby act as a form of active reflection — reviewing by doing. This type of direction may increase engagement and comprehension of concepts, especially when paired with a post-assessment that allows students to reflect on what they have learned.

Multiple Intelligences

Gardner (1983) famously asserted that individual students have unique intelligences. Linguistic intelligence is well served by text-based lesson delivery, but students with, for instance, (a) visual-spatial, (b) bodily-kinesthetic, or (c) interpersonal intelligences are not typically well served by online learning platforms. LinkedIn Learning videos have the potential to engage these underserved students by (a) presenting concepts spatially on the screen, (b) allowing students a chance to physically follow along with a modelled skill, and (c) adding a teacher-figure as the speaker and demonstrator in the video.

Self-Directed Learning

Self-directed learning is a key requirement of online learning. Online courses give students an opportunity to develop and practise self-direction, thereby encouraging students’ agency to decide where, when, and sometimes even how they will complete their lessons. Typically, adult learners value self-directed learning, since adults prefer to feel that they have choices and are learning voluntarily (Humber Centre for Teaching and Learning, n.d.). All LinkedIn Learning assets provide a helpful table of contents that allows students to navigate the video content and choose to review particular segments, while the player allows students to adjust speed. Students benefit greatly from this built-in customizability, as they can tailor the presentation to their learning preferences.

By optimizing these pedagogical approaches in the online learning context, it is possible to improve the learning experience for a large number of students who do not typically thrive in online learning contexts. LinkedIn Learning videos provide a unique opportunity to achieve this significant goal.

Instructional Design Considerations

Along with pedagogical considerations, instructional design principles should also influence the planning of any digital learning experience. When approaching any digital experience, the three principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), as set forth by Meyer, Rose, & Gordon (2014), provide an important framework:

- Multiple means of representation: giving learners various ways of acquiring information and knowledge

- Multiple means of expression: providing learners with alternatives for demonstrating what they know

- Multiple means of engagement: tapping into learners’ interests, offering appropriate challenges, and increasing motivation

The discussion below will reference these UDL principles, where applicable, as a rationale for design recommendations when LinkedIn Learning videos are deployed in online learning.

Practical Strategies for Implementing Video Assets in Online Learning Environments: A Case Study

Before discussing exemplary practices for deploying LinkedIn Learning videos, it is important to start at the beginning: the Getting Started section of an online course, which may be labelled differently at different schools. This section is where the course syllabus, course outline, instructor contact information, and other start-up information reside on an LMS. In a course that effectively leverages LinkedIn Learning video assets, the start-up module should also include an orientation to the LinkedIn Learning interface and player. An orientation is particularly important to students who are not computer savvy, students with language barriers, and students with disabilities. Subtitles, play speed, the table of contents, transcripts, and the search bar are extremely important to these learners. It is essential that they be made aware of the tools at their disposal and how to use them, as these tools empower students to learn in the way that is best for them. Fortunately, LinkedIn Learning has already created just such a tutorial. The “How to Use LinkedIn Learning ” video is very helpful. Take the time to direct students to Part 2: Watching the Training for the most relevant information.

Avoid the expectation that students will optimize their viewing experience intuitively. Students who lack a high comfort level with technology are often too intimidated to attempt customization, while other students who are used to teacher-directed learning need to be taught how to customize their learning experiences when given the opportunity. Teaching learners how to use the LinkedIn Learning tools places more power in their hands, contextualizing the LinkedIn Learning videos as an active viewing experience rather than a passive viewing experience. In an interesting study that has clear implications for the implementation of videos in e-learning, Craddock, Martinovic, and Lawson (2011) found that when viewers of an object controlled their view via a touch screen, they recognized what they were looking at much more quickly than those who did not have control over what they saw. The bottom line here is that online teachers should foster active viewing, which has obvious implications for learning faster and better, specifically by leveraging the benefits of Self-Directed Study (see Pedagogical Considerations) and by providing more paths for content delivery (UDL Principle 1).

Case Study: Context

In Humber College’s online business writing class BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing, students are encouraged to download a free student version of Microsoft Word 2016, and all submissions must be in .docx format. Although some students persist in using alternative word-processing software, which is acceptable as long as they are sufficiently skilled in that software, the vast majority of students use Word. Given students’ very diverse backgrounds, some have advanced knowledge of the software, while others struggle to understand the basics. Therefore, it is important to train students on Microsoft Word software so that all students feel confident as they complete course assignments.

Scheduling of the Word tutorial is key to maximizing impact. Students need to gain this information early enough for it to be helpful, but not so early that they forget what they have learned before they begin to apply the knowledge. In BICC 112, the Word tutorial appears in Module 1 in the very first week of class because the software is used throughout the course. Early introduction develops confidence and sets up the Word tutorials as reference points to be used throughout the course. Many students find this early introduction helpful.

Case Study: Application

When adding a video, such as the Word 2016 tutorial, to any online course, the worst possible approach is to place the link to the asset haphazardly, with no accompanying connective framework within the LMS. Instead, this report advocates ushering students through three learning phases when they encounter any video asset: (1) preparation, (2) integration, and (3) consolidation. These three phases will be discussed at length and illustrated with reference to the online BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing course currently offered by Humber College.

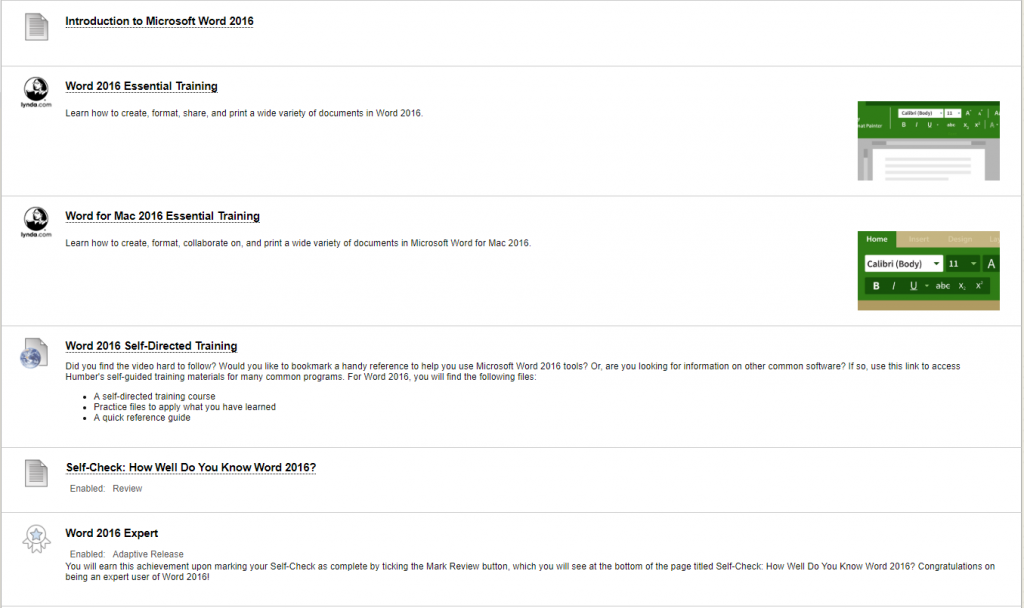

To provide context for this discussion, Figure 5.1 offers a practical illustration of the sequence of the three phases within BICC 112. Students must always encounter the preparation prior to the video. In Figure 5.1, the preparation is the page entitled “Introduction to Word 2016” (provided in full text below in Table 5.1). Then, in the integration phase, the videos appear, along with any alternative or supplementary learning materials. In this case, students have the option to choose the video that is applicable to their own computer (Mac or PC), and they are provided with a link to Humber’s text-based Microsoft Word 2016 training guide. Finally, in the consolidation phase, students are given confirmation materials — in this case, a self-check exercise (see Appendix A for full text) and its accompanying achievement badge.

Phase One: Preparation

When LinkedIn Learning videos are integrated into an LMS-based lesson, the LinkedIn Learning video links often self-populate with content when deployed in the LMS, displaying a brief summary of the video topic for students, a relevant image, and the LinkedIn Learning icon. Because this content is pre-set, there is no opportunity to customize the description in order to direct students’ attention; therefore, the preparation phase is essential to direct students as they watch a video. Figure 5.1 shows the placement of the preparation page titled “Introduction to Microsoft Word 2016” prior to the LinkedIn Learning videos in the BICC 112 example.

The preparation phase that should appear prior to any video asset consists of several possible steps, listed and described in this section. Keep in mind that one or more of these elements may be omitted when it does not apply to a particular video-based learning experience.

Step one: Assemble required equipment (UDL principle 1). It is important to note that students’ equipment varies. As an example, in BICC 112, students must have access to software tutorials for both Macs and PCs, and they should be clearly directed to choose the correct one between:

-

- Word 2016 Essential Training

- Word for Mac 2016 Essential Training

It is also important to direct students to download any software they may need prior to watching the video, and assemble any tools that they might require, such as writing utensils and paper to make notes. This step is not always necessary if specific equipment is not required to explore the subject matter.

Step two: Orient students if necessary. Since, in BICC 112, the Word tutorial videos are the first LinkedIn Learning assets that students encounter, it is important to remind them to watch the “How to Use Lynda.com” orientation video that is posted under Getting Started so they familiarize themselves with the LinkedIn Learning tools. Be sure to emphasize the importance of this orientation for students who lack familiarity with computers, speak English as a second language, or have a documented disability. Once students have accessed LinkedIn Learning resources numerous times, this step can be omitted.

Step three: Explain the “why” (UDL principle 3). As Malcolm Knowles puts it, “If we know why we are learning, and if the reason fits our needs as we perceive them, we will learn quickly and deeply” (Knowles, n.d.). Indeed, it is well documented that adult learners thrive when they perceive subject matter to be personally relevant (Humber Centre for Teaching and Learning, n.d.). Therefore, any video assets should be introduced with a statement of how they will be useful to students throughout the course or in the real world, thereby positioning students to want to learn what the videos have to offer.

Step four: Help students manage their time and prepare to learn. Avoid taking adult learners by surprise; always state the approximate length of a video when integrating it into a lesson, especially when they are quite long. In the case of BICC 112, both Word 2016 videos are over five hours long. Contemporary internet users are not necessarily accustomed to consuming lengthy videos on popular video-sharing platforms. In fact, according to statistics collected by a video production company, at the time of writing the average length of the 10 most popular YouTube videos was just 4 minutes, 20 seconds (MiniMatters, n.d.). Imagine students’ reactions when they expect a short clip and are still sitting there five hours later. By preparing the students for the time commitment that is required, instructors and designers can enable learners to set aside adequate time, divert distractions, and mentally prepare to engage their attention for a longer span.

Step five: Honour what is known (UDL principles 1 and 2). When teaching adults, it is important to establish what they already know to help learners feel that their knowledge and experience is being extended rather than dismissed (Humber Centre for Teaching and Learning, n.d.). Fortunately, in BICC 112, the Word 2016 tutorials include a useful diagnostic that helps students identify their own level of expertise and flag topics that they may wish to review, so it is a simple matter of directing the students’ attention to this feature. If no diagnostic was present, an instructor could also link to a third-party Microsoft Office quiz, or write his or her own pre-assessment.

Step six: Create a sense of choice (UDL principle 1). Adults learn better when they feel that they are voluntary learners who can make choices between learning materials (Humber Centre for Teaching and Learning, n.d.). In the BICC 112 example, instructional language seeks to highlight free choice by explaining the different paths that students can choose to take while progressing through the video tutorial. This study has already discussed the value of active viewing versus passive viewing. When applied to LinkedIn Learning videos, it is important to prepare students to be active viewers by emphasizing their personal agency and making it clear that they have control over the delivery of the video content and how they choose to progress through this content.

Step seven: Activate a variety of learning styles (UDL principle 1). As posited by Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (see Pedagogical Considerations), students learn in a variety of ways. From the instructional design perspective, it is important to implement the UDL principles when planning how to teach a lesson. Activate the power of learning styles by building in opportunities for different kinds of learning to take place. In BICC 112, the instructions encourage students to open Word 2016 and physically follow along with the steps in the video if they wish to do so. Students who are kinesthetic learners thrive when given these sorts of opportunities to learn by doing, while visual and auditory learners are more likely to forego following along in favour of absorbing the information with their full attention. Indicate any alternative learning avenues as well. For instance, BICC 112 students who are linguistic learners are provided with a text-based alternative to the videos in the form of a link to Humber College’s comprehensive proprietary software training guides.

Step eight: Preview the consolidation. Prepare students for the post-video consolidation of learning by briefly mentioning what the students should do after they complete the video. This technique helps students to plan their learning and manage their time effectively. Furthermore, as any teacher can tell you, students also tend to pay closer attention when they know a quiz is coming.

Table 5.1 shows the text that constitutes the preparation phase for the Word 2016 tutorial in BICC 112. All eight recommendations discussed in this section are indicated in the functions column next to the text that leverages each respective function, so the pedagogical objectives of all text should be clear.

| Introduction to Word 2016 | |

| Text | Functions |

| Although this is not a computer science course, knowledge of word-processing features is extremely important to designing a visually striking and reader-friendly document. The next activity in this module is a 5+ hour-long video from LinkedIn Learning entitled Word 2016 Essential Training, which will walk you through many of the key word-processing tools that you will use in this course and beyond. This video is very lengthy so do not feel that you need to watch it all. Use the table of contents to the left of the screen to watch just the topics that you are not already familiar with. | Explain the “why”; Help students manage their time and prepare to learn; Honour what is known; Create a sense of choice |

| First, to learn more about how to use the table of contents, the LinkedIn Learning video player, and other helpful tools provided by LinkedIn Learning , please be sure to watch the How to Use Lynda.com orientation video, which is posted in Getting Started. You should watch Part 2: Watching the Training. If you are not computer savvy, you speak English as a second language, or you are registered with Accessible Learning Services, please do not skip this step, as you will learn about several tools that will help you view the video in the way that works best for you. | Orient students if necessary; Honour what is known; Create a sense of choice |

| Next, be sure to download the latest version of Microsoft Word. Humber students can download the Microsoft Word program for free, for both PC and Mac operating systems. If you don’t already have this program installed on your computer, please download it now, so that you can follow along with the steps outlined in the training video, which is the next item in Module 1. | Assemble required equipment |

| Remember, Humber College provides Microsoft Office software free for any students! If you do not yet have Microsoft Word 2016, download your free software by clicking the button below [hyperlink is provided for students]. | Assemble required equipment |

| Now it’s almost time to watch the Microsoft Word 2016 training video. You’ll note that the following two items in Module 1 are training videos. Do not watch both videos; choose the correct video for your computer type (PC or Mac), and watch only the video that applies to you [PC users (Windows/Microsoft) should watch Word 2016 Essential Training; Mac users should watch Word for Mac 2016 Essential Training.] | Assemble required equipment; Help students manage their time and prepare to learn. |

| If you use Word 2016 on a regular basis, you might feel quite confident with the software already, or you may have no idea what your level of expertise might be. If either of these descriptions apply to you, be sure to take the “What do you already know?” diagnostic quiz that appears after the Introduction to the video. This quiz will help you pinpoint the topics you most need to review, and you can use the table of contents to skip what you already know. | Honour what is known; Create a sense of choice |

| As you watch, it is highly recommended that you open up Word and try to follow along with the examples you see on screen whenever a skill that is new to you is introduced. Since it can be difficult to watch a video on your computer and use Word on the same device, it is ideal if you have a second device you can use. Or, if it helps you follow along better, just jot notes as you watch. | Activate learning styles; Create a sense of choice |

| When you are finished watching the video, complete the ungraded self-check exercise titled Self-Check: How Well Do You Know Word? Feel free to refer back to the video, and to the supplemental Word 2016 Self-Directed Training web link to help you complete the self-check. Now, let’s watch and learn! | Preview the Consolidation |

Phase Two: Integration

The integration phase is very often simply the placement of the video, or videos, within a learning module, but it can also include alternative delivery methods for similar content to accommodate different learning styles (UDL principle 1). As already discussed, students in BICC 112 were offered a choice between two versions of the video: one for Mac users, and one for PC users. Students were also provided with a link to supplemental resources that contained the same information as the videos, but in a visual, text-based format, to provide an alternative learning method for linguistic learners. Figure 5.1 shows the placement of these items: the two videos followed by “Word 2016 Self-Directed Training,” which links to Humber College’s comprehensive software training guides.

Phase Three: Consolidation

After viewing the videos, students need to consolidate what they have learned. The word consolidation is used very intentionally here because this phase must accomplish two tasks that are both present in the dictionary definition of the word: (1) to make firm or solid any new learning so that it enters long-term memory, and (2) to unite two things (in this case, the video lesson must be connected with course concepts and real-world practice). An effective method for consolidating learning is to offer a post-assessment that will allow students to self-check their understanding. This post-assessment can take a variety of forms: a class discussion on the LMS discussion board, a quiz, or an exercise, to name a few (UDL principle 2). Regardless of what task is set, the substance of that task must be aimed at the consolidation of what was learned in the video.

In BICC 112, the post-assessment after the Word 2016 tutorial focused on real-world practice since the intent of this tutorial video was to enable practical application of skills that could be leveraged in future course assignments. Therefore, the post-assessment in this example was an exercise asking students to complete a series of tasks on a Word 2016 document in order to confirm their understanding of the video topics. This exercise is provided as a resource for instructors in Appendix A.

Of course, this assessment can be graded, but for those situations where the assessment is not graded, it is a great idea to attach some sort of achievement or commemoration to mark students’ progress. In BICC 112, students are awarded with an achievement badge when they mark the Self-Check exercise as complete (see Figure 5.1). Achievement badges can bring a sense of accomplishment and provide an incentive for students to engage with the post-assessment (UDL principle 3). Tasks with achievements attached tend to see a higher rate of completion, which results in more students learning.

Limitations and Challenges

Of course, as with any form of teaching and learning, there are limitations and challenges to this recommended three-phase approach to deploying LinkedIn Learning video assets in online learning environments.

First, this study only considers the problem of integrating LinkedIn Learning videos in a post-secondary, LMS-based online course. Traditional post-secondary learning is mostly push learning, which means that students progress through a curated course of learning, typically at a pre-set pace. The alternative, pull learning, is learner-initiated, often resembling just-in-time (JIT) style delivery, with short and precise microlessons accessed at the exact moment they are needed. This kind of learning is a major trend in corporate e-learning, so it is important to specify that the recommendations made in this report are developed with a curated course model in mind. They would require significant revision to be applicable for pull learning.

Second, it is always important to keep human factors in mind when discussing any human-used system. Learners are not perfect and so their learning will not be perfect, regardless of how extensively content delivery is optimized. As an example, in online learning, students who struggle to use technology often lack the ability to deep-dive into interface customization and learning tools, despite orientation and training. Meanwhile, students who come from an environment where learning is teacher-directed can feel overwhelmed and paralyzed when given too much choice in learning paths. Learning how to learn — particularly, scaffolding one’s own learning in an online context — is an important process for adult learners, and many will still be navigating this key life lesson as they encounter online materials. An online instructor should always strive to act as a resource to assist adult learners in building confidence with technology and developing their personal learning skills so they get the most out of any optimized e-learning design. An online instructor should also be forgiving when students struggle to master the demands of effective e-learning.

The recommendations springing from this single case study, particularly to do with writing the preparation and consolidation pages that should bracket pedagogically sound videos, are not exhaustive. Online instructors who would like to learn more about exemplary practices for using LinkedIn Learning to achieve the best possible outcomes in online teaching and learning can use the “Teaching with Lynda.com” video provided by LinkedIn Learning as a helpful resource.

Conclusions

By offering comprehensive and effective preparation and consolidation, placed pre- and post-video, instructors can maximize the pedagogical and design impact of video assets in an online course. Appendix B provides interested instructors with a helpful checklist for implementing the three-step design for integrating LinkedIn Learning videos in these phases: (1) the preparation phase, (2) the integration of video asset(s) and any alternative learning formats, and (3) the consolidation phase.

These recommendations will allow an instructor or course designer to include videos as a purposeful, well-integrated aspect of a lesson, rather than as outsourced instruction with little to no integration in the LMS materials. Students’ learning experiences are more fruitful when well-designed preparation and consolidation techniques surround the engaging and pedagogically sound instructional videos provided by LinkedIn Learning .

Appendix A: Consolidation Exercise

Self-Check: How Well Do You Know Word 2016?

By completing this self-check, you will ensure that you understand the major concepts you learned in the Word 2016 training videos. Refer back to the videos as needed to complete these tasks. Remember, you can use the LinkedIn Learning table of contents to navigate through the videos to the relevant topic.

For the Module 1 discussion, you will be asked to write an introduction that will present you to the class. Write a one-paragraph draft of this introduction (or paste it here if it is already complete) immediately below the self-check instructions. Then, follow the instructions below, in order:

- Add a title for your paragraph, which should be on its own line, centre-aligned, and bolded.

- Change the font of your introduction accordingly:

- Adjust the colour to a shade of your choice.

- Change the font style to a font of your choice.

- Add a text effect to the title.

- Add a page break between this instruction page and your introduction so that your introduction is on page two of this document.

- Add (a) a border and (b) shading for your introduction.

- Adjust the line spacing for your introduction so that it is double-spaced.

- Adjust the page margins to narrow.

- Add a watermark to the page.

- Add a list (either numbered or bulleted) to your paragraph.

- Add a small photograph of yourself to your page. Can you add a special effect to this photo?

- Run Spell Check.

- Use Track Changes to make three revisions to your paragraph.

Once you have completed these eleven steps, congratulate yourself on mastering Word 2016! Be sure to set this task as Reviewed to earn an achievement badge for your hard work.

Data Source: Humber College, 2019

Appendix B: Checklist for Integrating Video Assets in the Post-Secondary LMS

Phase One: Preparation

◊ Indicate required equipment or software, if necessary.

◊ Orient students to LinkedIn Learning , if necessary.

◊ Explain the reasons for watching the video, with connections to course content and real-w

◊ Indicate required equipment or software, if necessary.

◊ Orient students to LinkedIn Learning , if necessary.

◊ Explain the reasons for watching the video, with connections to course content and real-world practice.

◊ Help students manage their time and prepare to learn, by describing the length and delivery style of the video. Here are some sample questions to consider:

-

- Should students try to follow along with a tutorial?

- Should students take notes?

- How much time is needed to watch the video?

◊ Honour what is known: provide a diagnostic for students or a way to self-direct their learning path to the topics that are new, or require review.

◊ Create a sense of choice and foster active viewing.

◊ Activate learning styles by building in opportunities for different kinds of learning to take place.

◊ Preview the consolidation by briefly mentioning what the students should do after they complete the video.

◊ Phase Two: Integration

◊ Place video(s).

◊ Provide any supplemental or alternate links for different learning styles and abilities.

◊ Phase Three: Consolidation

◊ Provide a post-assessment that will allow students to self-check their understanding, connecting the video with broader course concepts or with real-world practice.

◊ Provide motivation and indicate completion: add a grade, a check mark, or an achievement marker.

List of LinkedIn Learning Videos

LinkedIn Learning Staff (2017, March 30). How to use Lynda.com [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/NA-tutorials/How-use-Lynda-com/77683-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a1%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3ahow+to+use+lynda.com%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2

Quigley, A., & Fishbach, M. (2016, May 31). Teaching with Lynda.com [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Educational-Technology-tutorials/Teaching-Lynda-com/487942-2.html

Rivers, D. (2015, August 7). Word for Mac 2016 essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Word-tutorials/Word-Mac-2016-Essential-Training/157347-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a2%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3amicrosoft+word+2016+mac%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2

Rivers, D. (2016, August 5). Word 2016 essential training [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Word-tutorials/Word-2016-Essential-Training/378044-2.html?srchtrk=index%3a8%0alinktypeid%3a2%0aq%3amicrosoft+word+2016%0apage%3a1%0as%3arelevance%0asa%3atrue%0aproducttypeid%3a2c

References

Collins, A., & Halverson, R. (2009). Rethinking education in the age of technology. New York: Teachers College Press.

Craddock, M., Martinovic, J., & Lawson, R. (2011). An advantage for active versus passive aperture-viewing in visual object recognition. Perception, 40 (10), 1154-1163.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Humber Centre for Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Teaching adult learners. Retrieved March 1, 2019 from http://centreforteachingandlearning.ca/modules/adult_education/plainlaunch.htm

Humber College (2019). Module 1: Introduction. In BICC 112 – Effective Business Writing [Course site]. Retrieved from https://learn.humber.ca

Knowles, M. (n.d.). Knowles quotation, “If we know why…we will learn quickly and deeply. Retrieved March 1, 2019 from http://www.experientiallearning.ucdavis.edu/module1/el1_20-knowlesquote.pdf

Lynda.com. (n.d.). About the Author: David Rivers. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from https://www.lynda.com/David-Rivers/33-1.html

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice (1st ed.). Wakefield, MA.: CAST.

MiniMatters (n.d.). The best video length for different videos on YouTube. Retrieved March 15, 2019 from https://www.minimatters.com/youtube-best-video-length