20 Sensation and Perception

Original chapter by Adam John Privitera adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

We encourage students to use the “Three-Step Method” for support in their learning. Please find our version of the Three-Step Method, created in collaboration with Queen’s Student Academic Success Services, at the following link: https://sass.queensu.ca/psyc100/

The topics of sensation and perception are among the oldest and most important in all of psychology. People are equipped with senses such as sight, hearing and taste that help us to take in the world around us. Amazingly, our senses have the ability to convert real-world information into electrical information that can be processed by the brain. The way we interpret this information– our perceptions– is what leads to our experiences of the world. In this module, you will learn about the biological processes of sensation and how these can be combined to create perceptions.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate the processes of sensation and perception.

- Explain the basic principles of sensation and perception.

- Describe the function of each of our senses.

- Outline the anatomy of the sense organs and their projections to the nervous system.

- Apply knowledge of sensation and perception to real world examples.

- Explain the consequences of multimodal perception.

Introduction

“Once I was hiking at Cape Lookout State Park in Tillamook, Oregon. After passing through a vibrantly colored, pleasantly scented, temperate rainforest, I arrived at a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. I grabbed the cold metal railing near the edge and looked out at the sea. Below me, I could see a pod of sea lions swimming in the deep blue water. All around me I could smell the salt from the sea and the scent of wet, fallen leaves.”

This description of a single memory highlights the way a person’s senses are so important to our experience of the world around us.

Before discussing each of our extraordinary senses individually, it is necessary to cover some basic concepts that apply to all of them. It is probably best to start with one very important distinction that can often be confusing: the difference between sensation and perception. The physical process during which our sensory organs—those involved with hearing and taste, for example—respond to external stimuli is called sensation. Sensation happens when you eat noodles or feel the wind on your face or hear a car horn honking in the distance. During sensation, our sense organs are engaging in transduction, the conversion of one form of energy into another. Physical energy such as light or a sound wave is converted into a form of energy the brain can understand: electrical stimulation. After our brain receives the electrical signals, we make sense of all this stimulation and begin to appreciate the complex world around us. This psychological process—making sense of the stimuli—is called perception. It is during this process that you are able to identify a gas leak in your home or a song that reminds you of a specific afternoon spent with friends.

Regardless of whether we are talking about sight or taste or any of the individual senses, there are a number of basic principles that influence the way our sense organs work. The first of these influences is our ability to detect an external stimulus. Each sense organ—our eyes or tongue, for instance—requires a minimal amount of stimulation in order to detect a stimulus. This absolute threshold explains why you don’t smell the perfume someone is wearing in a classroom unless they are somewhat close to you.

The way we measure absolute thresholds is by using a method called signal detection. This process involves presenting stimuli of varying intensities to a research participant in order to determine the level at which he or she can reliably detect stimulation in a given sense. During one type of hearing test, for example, a person listens to increasingly louder tones (starting from silence). This type of test is called the method of limits, and it is an effort to determine the point, or threshold, at which a person begins to hear a stimulus (see Additional Resources for a video demonstration). In the example of louder tones, the method of limits test is using ascending trials. Some method of limits tests use descending trials, such as making a light grow dimmer until a person can no longer see it. Correctly indicating that a sound was heard is called a hit; failing to do so is called a miss. Additionally, indicating that a sound was heard when one wasn’t played is called a false alarm, and correctly identifying when a sound wasn’t played is a correct rejection.

Through these and other studies, we have been able to gain an understanding of just how remarkable our senses are. For example, the human eye is capable of detecting candlelight from 30 miles away in the dark. We are also capable of hearing the ticking of a watch in a quiet environment from 20 feet away. If you think that’s amazing, I encourage you to read more about the extreme sensory capabilities of nonhuman animals; many animals possess what we would consider super-human abilities.

A similar principle to the absolute threshold discussed above underlies our ability to detect the difference between two stimuli of different intensities. The differential threshold, or just noticeable difference (JND), for each sense has been studied using similar methods to signal detection. To illustrate, find a friend and a few objects of known weight (you’ll need objects that weigh 1, 2, 10 and 11 lbs.—or in metric terms: 1, 2, 5 and 5.5 kg). Have your friend hold the lightest object (1 lb. or 1 kg). Then, replace this object with the next heaviest and ask him or her to tell you which one weighs more. Reliably, your friend will say the second object every single time. It’s extremely easy to tell the difference when something weighs double what another weighs! However, it is not so easy when the difference is a smaller percentage of the overall weight. It will be much harder for your friend to reliably tell the difference between 10 and 11 lbs. (or 5 versus 5.5 kg) than it is for 1 and 2 lbs. This is phenomenon is called Weber’s Law, and it is the idea that bigger stimuli require larger differences to be noticed.

Crossing into the world of perception, it is clear that our experience influences how our brain processes things. You have tasted food that you like and food that you don’t like. There are some bands you enjoy and others you can’t stand. However, during the time you first eat something or hear a band, you process those stimuli using bottom-up processing. This is when we build up to perception from the individual pieces. Sometimes, though, stimuli we’ve experienced in our past will influence how we process new ones. This is called top-down processing. The best way to illustrate these two concepts is with our ability to read. Read the following quote out loud

Notice anything odd while you were reading the text in the triangle? Did you notice the second “the”? If not, it’s likely because you were reading this from a top-down approach. Having a second “the” doesn’t make sense. We know this. Our brain knows this and doesn’t expect there to be a second one, so we have a tendency to skip right over it. In other words, your past experience has changed the way you perceive the writing in the triangle! A beginning reader—one who is using a bottom-up approach by carefully attending to each piece—would be less likely to make this error.

Finally, it should be noted that when we experience a sensory stimulus that doesn’t change, we stop paying attention to it. This is why we don’t feel the weight of our clothing, hear the hum of a projector in a lecture hall, or see all the tiny scratches on the lenses of our glasses. When a stimulus is constant and unchanging, we experience sensory adaptation. This occurs because if a stimulus does not change, our receptors quit responding to it. A great example of this occurs when we leave the radio on in our car after we park it at home for the night. When we listen to the radio on the way home from work the volume seems reasonable. However, the next morning when we start the car, we might be startled by how loud the radio is. We don’t remember it being that loud last night. What happened? We adapted to the constant stimulus (the radio volume) over the course of the previous day and increased the volume at various times.

Now that we have introduced some basic sensory principles, let us take on each one of our fascinating senses individually.

Vision

How vision works

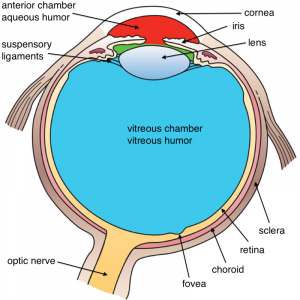

Vision is a tricky matter. When we see a pizza, a feather, or a hammer, we are actually seeing light bounce off that object and into our eye. Light enters the eye through the pupil, a tiny opening behind the cornea. The pupil regulates the amount of light entering the eye by contracting (getting smaller) in bright light and dilating (getting larger) in dimmer light. Once past the pupil, light passes through the lens, which focuses an image on a thin layer of cells in the back of the eye, called the retina.

Because we have two eyes in different locations, the image focused on each retina is from a slightly different angle (binocular disparity), providing us with our perception of 3D space (binocular vision). You can appreciate this by holding a pen in your hand, extending your arm in front of your face, and looking at the pen while closing each eye in turn. Pay attention to the apparent position of the pen relative to objects in the background. Depending on which eye is open, the pen appears to jump back and forth! This is how video game manufacturers create the perception of 3D without special glasses; two slightly different images are presented on top of one another.

It is in the retina that light is transduced, or converted into electrical signals, by specialized cells called photoreceptors. The retina contains two main kinds of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are primarily responsible for our ability to see in dim light conditions, such as during the night. Cones, on the other hand, provide us with the ability to see color and fine detail when the light is brighter. Rods and cones differ in their distribution across the retina, with the highest concentration of cones found in the fovea (the central region of focus), and rods dominating the periphery (see Figure 2). The difference in distribution can explain why looking directly at a dim star in the sky makes it seem to disappear; there aren’t enough rods to process the dim light!

Next, the electrical signal is sent through a layer of cells in the retina, eventually traveling down the optic nerve. After passing through the thalamus, this signal makes it to the primary visual cortex, where information about light orientation and movement begin to come together (Hubel & Wiesel, 1962). Information is then sent to a variety of different areas of the cortex for more complex processing. Some of these cortical regions are fairly specialized—for example, for processing faces (fusiform face area) and body parts (extrastriate body area). Damage to these areas of the cortex can potentially result in a specific kind of agnosia, whereby a person loses the ability to perceive visual stimuli. A great example of this is illustrated in the writing of famous neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks; he experienced prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces. These specialized regions for visual recognition comprise the ventral pathway (also called the “what” pathway). Other areas involved in processing location and movement make up the dorsal pathway (also called the “where” pathway). Together, these pathways process a large amount of information about visual stimuli (Goodale & Milner, 1992). Phenomena we often refer to as optical illusions provide misleading information to these “higher” areas of visual processing.

Dark and light adaptation

Humans have the ability to adapt to changes in light conditions. As mentioned before, rods are primarily involved in our ability to see in dim light. They are the photoreceptors responsible for allowing us to see in a dark room. You might notice that this night vision ability takes around 10 minutes to turn on, a process called dark adaptation. This is because our rods become bleached in normal light conditions and require time to recover. We experience the opposite effect when we leave a dark movie theatre and head out into the afternoon sun. During light adaptation, a large number of rods and cones are bleached at once, causing us to be blinded for a few seconds. Light adaptation happens almost instantly compared with dark adaptation. Interestingly, some people think pirates wore a patch over one eye in order to keep it adapted to the dark while the other was adapted to the light. If you want to turn on a light without losing your night vision, don’t worry about wearing an eye patch, just use a red light; this wavelength doesn’t bleach your rods.

Color vision

Our cones allow us to see details in normal light conditions, as well as color. We have cones that respond preferentially, not exclusively, for red, green and blue (Svaetichin, 1955). This trichromatic theory is not new; it dates back to the early 19th century (Young, 1802; Von Helmholtz, 1867). This theory, however, does not explain the odd effect that occurs when we look at a white wall after staring at a picture for around 30 seconds. Try this: stare at the image of the flag in Figure 3 for 30 seconds and then immediately look at a sheet of white paper or a wall. According to the trichromatic theory of color vision, you should see white when you do that. Is that what you experienced? As you can see, the trichromatic theory doesn’t explain the afterimage you just witnessed. This is where the opponent-process theory comes in (Hering, 1920). This theory states that our cones send information to retinal ganglion cells that respond to pairs of colors (red-green, blue-yellow, black-white). These specialized cells take information from the cones and compute the difference between the two colors—a process that explains why we cannot see reddish-green or bluish-yellow, as well as why we see afterimages. Color deficient vision can result from issues with the cones or retinal ganglion cells involved in color vision.

Hearing (Audition)

Some of the most well-known celebrities and top earners in the world are musicians. Our worship of musicians may seem silly when you consider that all they are doing is vibrating the air a certain way to create sound waves, the physical stimulus for audition.

People are capable of getting a large amount of information from the basic qualities of sound waves. The amplitude (or intensity) of a sound wave codes for the loudness of a stimulus; higher amplitude sound waves result in louder sounds. The pitch of a stimulus is coded in the frequency of a sound wave; higher frequency sounds are higher pitched. We can also gauge the quality, or timbre, of a sound by the complexity of the sound wave. This allows us to tell the difference between bright and dull sounds as well as natural and synthesized instruments (Välimäki & Takala, 1996).

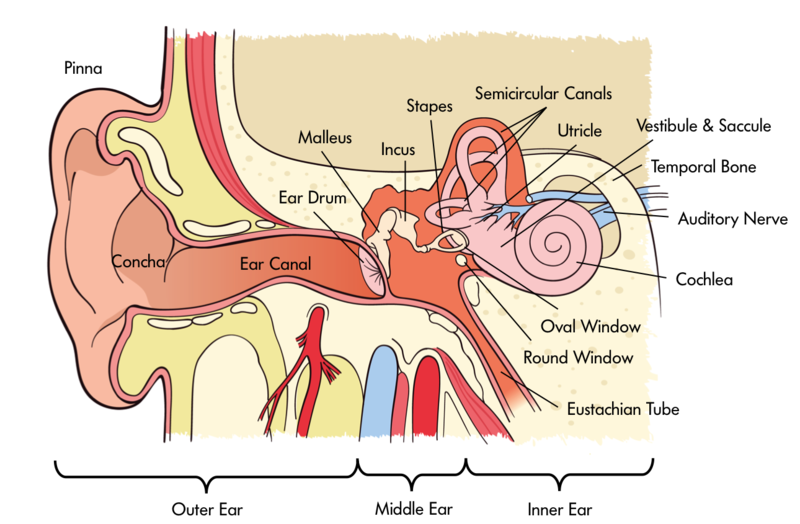

In order for us to sense sound waves from our environment they must reach our inner ear. Lucky for us, we have evolved tools that allow those waves to be funneled and amplified during this journey. Initially, sound waves are funneled by your pinna (the external part of your ear that you can actually see) into your auditory canal (the hole you stick Q-tips into despite the box advising against it). During their journey, sound waves eventually reach a thin, stretched membrane called the tympanic membrane (eardrum), which vibrates against the three smallest bones in the body—the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil), and the stapes (stirrup)—collectively called the ossicles. Both the tympanic membrane and the ossicles amplify the sound waves before they enter the fluid-filled cochlea, a snail-shell-like bone structure containing auditory hair cells arranged on the basilar membrane (see Figure 4) according to the frequency they respond to (called tonotopic organization). Depending on age, humans can normally detect sounds between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. It is inside the cochlea that sound waves are converted into an electrical message.

Because we have an ear on each side of our head, we are capable of localizing sound in 3D space pretty well (in the same way that having two eyes produces 3D vision). Have you ever dropped something on the floor without seeing where it went? Did you notice that you were somewhat capable of locating this object based on the sound it made when it hit the ground? We can reliably locate something based on which ear receives the sound first. What about the height of a sound? If both ears receive a sound at the same time, how are we capable of localizing sound vertically? Research in cats (Populin & Yin, 1998) and humans (Middlebrooks & Green, 1991) has pointed to differences in the quality of sound waves depending on vertical positioning.

After being processed by auditory hair cells, electrical signals are sent through the cochlear nerve (a division of the vestibulocochlear nerve) to the thalamus, and then the primary auditory cortex of the temporal lobe. Interestingly, the tonotopic organization of the cochlea is maintained in this area of the cortex (Merzenich, Knight, & Roth, 1975; Romani, Williamson, & Kaufman, 1982). However, the role of the primary auditory cortex in processing the wide range of features of sound is still being explored (Walker, Bizley, & Schnupp, 2011).

Balance and the vestibular system

The inner ear isn’t only involved in hearing; it’s also associated with our ability to balance and detect where we are in space. The vestibular system is comprised of three semicircular canals—fluid-filled bone structures containing cells that respond to changes in the head’s orientation in space. Information from the vestibular system is sent through the vestibular nerve (the other division of the vestibulocochlear nerve) to muscles involved in the movement of our eyes, neck, and other parts of our body. This information allows us to maintain our gaze on an object while we are in motion. Disturbances in the vestibular system can result in issues with balance, including vertigo.

Touch

Who doesn’t love the softness of an old t-shirt or the smoothness of a clean shave? Who actually enjoys having sand in their swimsuit? Our skin, the body’s largest organ, provides us with all sorts of information, such as whether something is smooth or bumpy, hot or cold, or even if it’s painful. Somatosensation—which includes our ability to sense touch, temperature and pain—transduces physical stimuli, such as fuzzy velvet or scalding water, into electrical potentials that can be processed by the brain.

Tactile sensation

Tactile stimuli—those that are associated with texture—are transduced by special receptors in the skin called mechanoreceptors. Just like photoreceptors in the eye and auditory hair cells in the ear, these allow for the conversion of one kind of energy into a form the brain can understand.

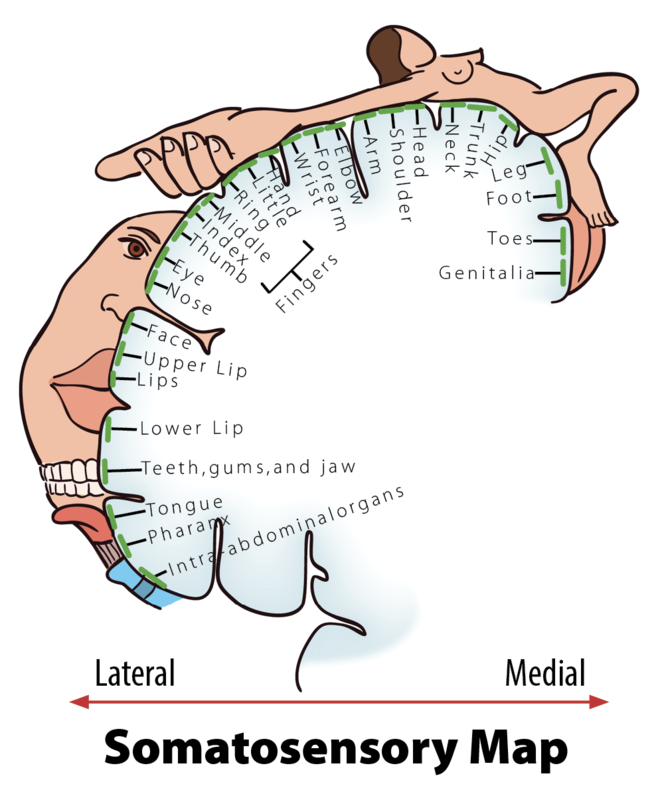

After tactile stimuli are converted by mechanoreceptors, information is sent through the thalamus to the primary somatosensory cortex for further processing. This region of the cortex is organized in a somatotopic map where different regions are sized based on the sensitivity of specific parts on the opposite side of the body (Penfield & Rasmussen, 1950). Put simply, various areas of the skin, such as lips and fingertips, are more sensitive than others, such as shoulders or ankles. This sensitivity can be represented with the distorted proportions of the human body shown in Figure 5.

Pain

Most people, if asked, would love to get rid of pain (nociception), because the sensation is very unpleasant and doesn’t appear to have obvious value. But the perception of pain is our body’s way of sending us a signal that something is wrong and needs our attention. Without pain, how would we know when we are accidentally touching a hot stove, or that we should rest a strained arm after a hard workout?

Phantom limbs

Records of people experiencing phantom limbs after amputations have been around for centuries (Mitchell, 1871). As the name suggests, people with a phantom limb have the sensations such as itching seemingly coming from their missing limb. A phantom limb can also involve phantom limb pain, sometimes described as the muscles of the missing limb uncomfortably clenching. While the mechanisms underlying these phenomena are not fully understood, there is evidence to support that the damaged nerves from the amputation site are still sending information to the brain (Weinstein, 1998) and that the brain is reacting to this information (Ramachandran & Rogers-Ramachandran, 2000). There is an interesting treatment for the alleviation of phantom limb pain that works by tricking the brain, using a special mirror box to create a visual representation of the missing limb. The technique allows the patient to manipulate this representation into a more comfortable position (Ramachandran & Rogers-Ramachandran, 1996).

Smell and Taste: The Chemical Senses

The two most underappreciated senses can be lumped into the broad category of chemical senses. Both olfaction (smell) and gustation (taste) require the transduction of chemical stimuli into electrical potentials. I say these senses are underappreciated because most people would give up either one of these if they were forced to give up a sense. While this may not shock a lot of readers, take into consideration how much money people spend on the perfume industry annually ($29 billion US Dollars). Many of us pay a lot more for a favorite brand of food because we prefer the taste. Clearly, we humans care about our chemical senses.

Olfaction (smell)

Unlike any of the other senses discussed so far, the receptors involved in our perception of both smell and taste bind directly with the stimuli they transduce. Odorants in our environment, very often mixtures of them, bind with olfactory receptors found in the olfactory epithelium. The binding of odorants to receptors is thought to be similar to how a lock and key operates, with different odorants binding to different specialized receptors based on their shape. However, the shape theory of olfaction isn’t universally accepted and alternative theories exist, including one that argues that the vibrations of odorant molecules correspond to their subjective smells (Turin, 1996). Regardless of how odorants bind with receptors, the result is a pattern of neural activity. It is thought that our memories of these patterns of activity underlie our subjective experience of smell (Shepherd, 2005). Interestingly, because olfactory receptors send projections to the brain through the cribriform plate of the skull, head trauma has the potential to cause anosmia, due to the severing of these connections. If you are in a line of work where you constantly experience head trauma (e.g. professional boxer) and you develop anosmia, don’t worry—your sense of smell will probably come back (Sumner, 1964).

Gustation (taste)

Taste works in a similar fashion to smell, only with receptors found in the taste buds of the tongue, called taste receptor cells. To clarify a common misconception, taste buds are not the bumps on your tongue (papillae), but are located in small divots around these bumps. These receptors also respond to chemicals from the outside environment, except these chemicals, called tastants, are contained in the foods we eat. The binding of these chemicals with taste receptor cells results in our perception of the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (savory)—although some scientists argue that there are more (Stewart et al., 2010). Researchers used to think these tastes formed the basis for a map-like organization of the tongue; there was even a clever rationale for the concept, about how the back of the tongue sensed bitter so we would know to spit out poisons, and the front of the tongue sensed sweet so we could identify high-energy foods. However, we now know that all areas of the tongue with taste receptor cells are capable of responding to every taste (Chandrashekar, Hoon, Ryba, & Zuker, 2006).

During the process of eating we are not limited to our sense of taste alone. While we are chewing, food odorants are forced back up to areas that contain olfactory receptors. This combination of taste and smell gives us the perception of flavor. If you have doubts about the interaction between these two senses, I encourage you to think back to consider how the flavors of your favorite foods are impacted when you have a cold; everything is pretty bland and boring, right?

Putting it all Together: Multimodal Perception

Though we have spent the majority of this module covering the senses individually, our real-world experience is most often multimodal, involving combinations of our senses into one perceptual experience. This should be clear after reading the description of walking through the forest at the beginning of the module; it was the combination of senses that allowed for that experience. It shouldn’t shock you to find out that at some point information from each of our senses becomes integrated. Information from one sense has the potential to influence how we perceive information from another, a process called multimodal perception.

Interestingly, we actually respond more strongly to multimodal stimuli compared to the sum of each single modality together, an effect called the superadditive effect of multisensory integration. This can explain how you’re still able to understand what friends are saying to you at a loud concert, as long as you are able to get visual cues from watching them speak. If you were having a quiet conversation at a café, you likely wouldn’t need these additional cues. In fact, the principle of inverse effectiveness states that you are less likely to benefit from additional cues from other modalities if the initial unimodal stimulus is strong enough (Stein & Meredith, 1993).

Because we are able to process multimodal sensory stimuli, and the results of those processes are qualitatively different from those of unimodal stimuli, it’s a fair assumption that the brain is doing something qualitatively different when they’re being processed. There has been a growing body of evidence since the mid-90’s on the neural correlates of multimodal perception. For example, neurons that respond to both visual and auditory stimuli have been identified in the superior temporal sulcus (Calvert, Hansen, Iversen, & Brammer, 2001). Additionally, multimodal “what” and “where” pathways have been proposed for auditory and tactile stimuli (Renier et al., 2009). We aren’t limited to reading about these regions of the brain and what they do; we can experience them with a few interesting examples including the McGurk Effect and Double Flash Illusion.

To experience the Double Flash illusion, please see this demo from Dr. Ladan Shams’ lab at UCLA: https://shamslab.psych.ucla.edu/demos/

Conclusion

Our impressive sensory abilities allow us to experience the most enjoyable and most miserable experiences, as well as everything in between. Our eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin provide an interface for the brain to interact with the world around us. While there is simplicity in covering each sensory modality independently, we are organisms that have evolved the ability to process multiple modalities as a unified experience.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- Absolute threshold

- The smallest amount of stimulation needed for detection by a sense.

- Agnosia

- Loss of the ability to perceive stimuli.

- Anosmia

- Loss of the ability to smell.

- Audition

- Ability to process auditory stimuli. Also called hearing.

- Auditory canal

- Tube running from the outer ear to the middle ear.

- Auditory hair cells

- Receptors in the cochlea that transduce sound into electrical potentials.

- Binocular disparity

- Difference is images processed by the left and right eyes.

- Binocular vision

- Our ability to perceive 3D and depth because of the difference between the images on each of our retinas.

- Bottom-up processing

- Building up to perceptual experience from individual pieces.

- Chemical senses

- Our ability to process the environmental stimuli of smell and taste.

- Cochlea

- Spiral bone structure in the inner ear containing auditory hair cells.

- Cones

- Photoreceptors of the retina sensitive to color. Located primarily in the fovea.

- Dark adaptation

- Adjustment of eye to low levels of light.

- Differential threshold

- The smallest difference needed in order to differentiate two stimuli. (See Just Noticeable Difference (JND))

- Dorsal pathway

- Pathway of visual processing. The “where” pathway.

- Flavor

- The combination of smell and taste.

- Gustation

- Ability to process gustatory stimuli. Also called taste.

- Just noticeable difference (JND)

- The smallest difference needed in order to differentiate two stimuli. (see Differential Threshold)

- Light adaptation

- Adjustment of eye to high levels of light.

- Mechanoreceptors

- Mechanical sensory receptors in the skin that response to tactile stimulation.

- Multimodal perception

- The effects that concurrent stimulation in more than one sensory modality has on the perception of events and objects in the world.

- Nociception

- Our ability to sense pain.

- Odorants

- Chemicals transduced by olfactory receptors.

- Olfaction

- Ability to process olfactory stimuli. Also called smell.

- Olfactory epithelium

- Organ containing olfactory receptors.

- Opponent-process theory

- Theory proposing color vision as influenced by cells responsive to pairs of colors.

- Ossicles

- A collection of three small bones in the middle ear that vibrate against the tympanic membrane.

- Perception

- The psychological process of interpreting sensory information.

- Phantom limb

- The perception that a missing limb still exists.

- Phantom limb pain

- Pain in a limb that no longer exists.

- Pinna

- Outermost portion of the ear.

- Primary auditory cortex

- Area of the cortex involved in processing auditory stimuli.

- Primary somatosensory cortex

- Area of the cortex involved in processing somatosensory stimuli.

- Primary visual cortex

- Area of the cortex involved in processing visual stimuli.

- Principle of inverse effectiveness

- The finding that, in general, for a multimodal stimulus, if the response to each unimodal component (on its own) is weak, then the opportunity for multisensory enhancement is very large. However, if one component—by itself—is sufficient to evoke a strong response, then the effect on the response gained by simultaneously processing the other components of the stimulus will be relatively small.

- Retina

- Cell layer in the back of the eye containing photoreceptors.

- Rods

- Photoreceptors of the retina sensitive to low levels of light. Located around the fovea.

- Sensation

- The physical processing of environmental stimuli by the sense organs.

- Sensory adaptation

- Decrease in sensitivity of a receptor to a stimulus after constant stimulation.

- Shape theory of olfaction

- Theory proposing that odorants of different size and shape correspond to different smells.

- Signal detection

- Method for studying the ability to correctly identify sensory stimuli.

- Somatosensation

- Ability to sense touch, pain and temperature.

- Somatotopic map

- Organization of the primary somatosensory cortex maintaining a representation of the arrangement of the body.

- Sound waves

- Changes in air pressure. The physical stimulus for audition.

- Superadditive effect of multisensory integration

- The finding that responses to multimodal stimuli are typically greater than the sum of the independent responses to each unimodal component if it were presented on its own.

- Tastants

- Chemicals transduced by taste receptor cells.

- Taste receptor cells

- Receptors that transduce gustatory information.

- Top-down processing

- Experience influencing the perception of stimuli.

- Transduction

- The conversion of one form of energy into another.

- Trichromatic theory

- Theory proposing color vision as influenced by three different cones responding preferentially to red, green and blue.

- Tympanic membrane

- Thin, stretched membrane in the middle ear that vibrates in response to sound. Also called the eardrum.

- Ventral pathway

- Pathway of visual processing. The “what” pathway.

- Vestibular system

- Parts of the inner ear involved in balance.

- Weber’s law

- States that just noticeable difference is proportional to the magnitude of the initial stimulus.

-

References

- Calvert, G. A., Hansen, P. C., Iversen, S. D., & Brammer, M. J. (2001). Detection of audio-visual integration sites in humans by application of electrophysiological criteria to the BOLD effect. Neuroimage, 14(2), 427-438.

- Chandrashekar, J., Hoon, M. A., Ryba, N. J., & Zuker, C. S. (2006). The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature, 444(7117), 288-294.

- Goodale, M. A., & Milner, A. D. (1992). Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in Neurosciences, 15(1), 20-25.

- Hering, E. (1920). Grundzüge der Lehre vom Lichtsinn. J.Springer.

- Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (1962). Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. The Journal of Physiology,160(1), 106.

- Merzenich, M. M., Knight, P. L., & Roth, G. L. (1975). Representation of cochlea within primary auditory cortex in the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology, 38(2), 231-249.

- Middlebrooks, J. C., & Green, D. M. (1991). Sound localization by human listeners. Annual Review of Psychology, 42(1), 135-159.

- Mitchell, S. W. (1871). Phantom limbs. Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, 8, 563-569.

- Penfield, W., & Rasmussen, T. (1950). The cerebral cortex of man; a clinical study of localization of function. Oxford: England

- Populin, L. C., & Yin, T. C. (1998). Behavioral studies of sound localization in the cat. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18(6), 2147-2160.

- Ramachandran, V. S., & Rogers-Ramachandran, D. (2000). Phantom limbs and neural plasticity. Archives of Neurology, 57(3), 317-320.

- Ramachandran, V. S., & Rogers-Ramachandran, D. (1996). Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 263(1369), 377-386.

- Renier, L. A., Anurova, I., De Volder, A. G., Carlson, S., VanMeter, J., & Rauschecker, J. P. (2009). Multisensory integration of sounds and vibrotactile stimuli in processing streams for “what” and “where”. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(35), 10950-10960.

- Romani, G. L., Williamson, S. J., & Kaufman, L. (1982). Tonotopic organization of the human auditory cortex. Science, 216(4552), 1339-1340.

- Shepherd, G. M. (2005). Outline of a theory of olfactory processing and its relevance to humans. Chemical Senses, 30(suppl 1), i3-i5.

- Stein, B. E., & Meredith, M. A. (1993). The merging of the senses. The MIT Press.

- Stewart, J. E., Feinle-Bisset, C., Golding, M., Delahunty, C., Clifton, P. M., & Keast, R. S. (2010). Oral sensitivity to fatty acids, food consumption and BMI in human subjects. British Journal of Nutrition, 104(01), 145-152.

- Sumner, D. (1964). Post Traumatic Anosmia. Brain, 87(1), 107-120.

- Svaetichin, G. (1955). Spectral response curves from single cones. Acta physiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 39(134), 17-46.

- Turin, L. (1996). A spectroscopic mechanism for primary olfactory reception. Chemical Senses, 21(6), 773-791.

- Von Helmholtz, H. (1867). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik (Vol. 9). Voss.

- Välimäki, V., & Takala, T. (1996). Virtual musical instruments—natural sound using physical models. Organised Sound, 1(02), 75-86.

- Walker, K. M., Bizley, J. K., King, A. J., & Schnupp, J. W. (2011). Multiplexed and robust representations of sound features in auditory cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(41), 14565-14576.

- Weinstein, S. M. (1998). Phantom limb pain and related disorders. Neurologic Clinics, 16(4), 919-935.

- Young, T. (1802). The Bakerian lecture: On the theory of light and colours. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London, 12-48.

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Privitera, A. J. (2019). Sensation and perception. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/xgk3ajhy

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/xgk3ajhy.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.

The physical processing of environmental stimuli by the sense organs.

A process in which physical energy converts into neural energy.

The psychological process of interpreting sensory information.

The smallest amount of stimulation needed for detection by a sense.

Method for studying the ability to correctly identify sensory stimuli.

The smallest difference needed in order to differentiate two stimuli. (See Just Noticeable Difference (JND))

The smallest difference needed in order to differentiate two stimuli. (see Differential Threshold)

States that just noticeable difference is proportional to the magnitude of the initial stimulus.

Building up to perceptual experience from individual pieces.

Experience influencing the perception of stimuli.

Decrease in sensitivity of a receptor to a stimulus after constant stimulation.

Cell layer in the back of the eye containing photoreceptors.

Difference is images processed by the left and right eyes.

Our ability to perceive 3D and depth because of the difference between the images on each of our retinas.

Photoreceptors of the retina sensitive to low levels of light. Located around the fovea.

Photoreceptors of the retina sensitive to color. Located primarily in the fovea.

Area of the cortex involved in processing visual stimuli.

Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (1962). Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat's visual cortex. The Journal of Physiology,160(1), 106.

Loss of the ability to perceive stimuli.

Pathway of visual processing. The “what” pathway.

Pathway of visual processing. The “where” pathway.

Goodale, M. A., & Milner, A. D. (1992). Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in Neurosciences, 15(1), 20-25.

Adjustment of eye to low levels of light.

Adjustment of eye to high levels of light.

Svaetichin, G. (1955). Spectral response curves from single cones. Acta physiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 39(134), 17-46.

Theory proposing color vision as influenced by three different cones responding preferentially to red, green and blue.

Young, T. (1802). The Bakerian lecture: On the theory of light and colours. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London, 12-48.

Von Helmholtz, H. (1867). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik (Vol. 9). Voss.

Theory proposing color vision as influenced by cells responsive to pairs of colors.

Hering, E. (1920). Grundzüge der Lehre vom Lichtsinn. J.Springer.

Changes in air pressure. The physical stimulus for audition.

Ability to process auditory stimuli. Also called hearing.

Välimäki, V., & Takala, T. (1996). Virtual musical instruments—natural sound using physical models. Organised Sound, 1(02), 75-86.

Outermost portion of the ear.

Tube running from the outer ear to the middle ear.

Thin, stretched membrane in the middle ear that vibrates in response to sound. Also called the eardrum.

A collection of three small bones in the middle ear that vibrate against the tympanic membrane.

Spiral bone structure in the inner ear containing auditory hair cells.

Receptors in the cochlea that transduce sound into electrical potentials.

Populin, L. C., & Yin, T. C. (1998). Behavioral studies of sound localization in the cat. The Journal of Neuroscience, 18(6), 2147-2160.

Middlebrooks, J. C., & Green, D. M. (1991). Sound localization by human listeners. Annual Review of Psychology, 42(1), 135-159.

Area of the cortex involved in processing auditory stimuli.

Merzenich, M. M., Knight, P. L., & Roth, G. L. (1975). Representation of cochlea within primary auditory cortex in the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology, 38(2), 231-249.

Romani, G. L., Williamson, S. J., & Kaufman, L. (1982). Tonotopic organization of the human auditory cortex. Science, 216(4552), 1339-1340.

Walker, K. M., Bizley, J. K., King, A. J., & Schnupp, J. W. (2011). Multiplexed and robust representations of sound features in auditory cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(41), 14565-14576.

Parts of the inner ear involved in balance.

Ability to sense touch, pain and temperature.

Mechanical sensory receptors in the skin that response to tactile stimulation.

A strip of cerebral tissue just behind the central sulcus engaged in sensory reception of bodily sensations.

Organization of the primary somatosensory cortex maintaining a representation of the arrangement of the body.

Penfield, W., & Rasmussen, T. (1950). The cerebral cortex of man; a clinical study of localization of function. Oxford: England

Our ability to sense pain.

The perception that a missing limb still exists.

Mitchell, S. W. (1871). Phantom limbs. Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, 8, 563-569.

Pain in a limb that no longer exists.

Weinstein, S. M. (1998). Phantom limb pain and related disorders. Neurologic Clinics, 16(4), 919-935.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Rogers-Ramachandran, D. (2000). Phantom limbs and neural plasticity. Archives of Neurology, 57(3), 317-320.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Rogers-Ramachandran, D. (1996). Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 263(1369), 377-386.

Our ability to process the environmental stimuli of smell and taste.

Ability to process olfactory stimuli. Also called smell.

Ability to process gustatory stimuli. Also called taste.

Chemicals transduced by olfactory receptors.

Organ containing olfactory receptors.

Theory proposing that odorants of different size and shape correspond to different smells.

Turin, L. (1996). A spectroscopic mechanism for primary olfactory reception. Chemical Senses, 21(6), 773-791.

Shepherd, G. M. (2005). Outline of a theory of olfactory processing and its relevance to humans. Chemical Senses, 30(suppl 1), i3-i5.

Loss of the ability to smell.

Sumner, D. (1964). Post Traumatic Anosmia. Brain, 87(1), 107-120.

Receptors that transduce gustatory information.

Chemicals transduced by taste receptor cells.

Stewart, J. E., Feinle-Bisset, C., Golding, M., Delahunty, C., Clifton, P. M., & Keast, R. S. (2010). Oral sensitivity to fatty acids, food consumption and BMI in human subjects. British Journal of Nutrition, 104(01), 145-152.

Chandrashekar, J., Hoon, M. A., Ryba, N. J., & Zuker, C. S. (2006). The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature, 444(7117), 288-294.

The combination of smell and taste.

The effects that concurrent stimulation in more than one sensory modality has on the perception of events and objects in the world.

The finding that responses to multimodal stimuli are typically greater than the sum of the independent responses to each unimodal component if it were presented on its own.

The finding that, in general, for a multimodal stimulus, if the response to each unimodal component (on its own) is weak, then the opportunity for multisensory enhancement is very large. However, if one component—by itself—is sufficient to evoke a strong response, then the effect on the response gained by simultaneously processing the other components of the stimulus will be relatively small.

Stein, B. E., & Meredith, M. A. (1993). The merging of the senses. The MIT Press.

Calvert, G. A., Hansen, P. C., Iversen, S. D., & Brammer, M. J. (2001). Detection of audio-visual integration sites in humans by application of electrophysiological criteria to the BOLD effect. Neuroimage, 14(2), 427-438.

Renier, L. A., Anurova, I., De Volder, A. G., Carlson, S., VanMeter, J., & Rauschecker, J. P. (2009). Multisensory integration of sounds and vibrotactile stimuli in processing streams for “what” and “where”. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(35), 10950-10960.