65 Exploring Attitudes and Changing Attitudes Through Persuasion

Original chapter from Principles of Social Psychology adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

We encourage students to use the “Three-Step Method” for support in their learning. Please find our version of the Three-Step Method, created in collaboration with Queen’s Student Academic Success Services, at the following link: https://sass.queensu.ca/psyc100/

You’ll notice that this chapter looks a bit different from our earlier chapters. A benefit of an Open Access textbook is that we have the ability to source and adapt content written by experts globally that address issues that are important for our course. This chapter is from the text “Principles of Social Psychology.” You can find the book here.

Exploring Attitudes

Learning Objectives

- Define the concept of attitude and explain why it is of such interest to social psychologists.

- Review the variables that determine attitude strength.

- Outline the factors affect the strength of the attitude-behavior relationship.

Although we might use the term in a different way in our everyday life (“Hey, he’s really got an attitude!”), social psychologists reserve the term attitude to refer to our relatively enduring evaluation of something, where the something is called the attitude object. The attitude object might be a person, a product, or a social group (Albarracín, Johnson, & Zanna, 2005; Wood & Quinn, 2003). In this section we will consider the nature and strength of attitudes and the conditions under which attitudes best predict our behaviors.

Attitudes Are Evaluations

When we say that attitudes are evaluations, we mean that they involve a preference for or against the attitude object, as commonly expressed in such terms as prefer, like, dislike, hate, and love. When we express our attitudes—for instance, when we say, “I love Cheerios,” “I hate snakes,” “I’m crazy about Bill,” or “I like Italians”—we are expressing the relationship (either positive or negative) between the self and an attitude object. Statements such as these make it clear that attitudes are an important part of the self-concept—attitudes tie the self-concept to the attitude object, and so our attitudes are an essential part of “us.”

Every human being holds thousands of attitudes, including those about family and friends, political parties and political figures, abortion rights and terrorism, preferences for music, and much more. Each of our attitudes has its own unique characteristics, and no two attitudes come to us or influence us in quite the same way. Research has found that some of our attitudes are inherited, at least in part, via genetic transmission from our parents (Olson, Vernon, Harris, & Jang, 2001). Other attitudes are learned mostly through direct and indirect experiences with the attitude objects (De Houwer, Thomas, & Baeyens, 2001). We may like to ride roller coasters in part because our genetic code has given us a thrill-loving personality and in part because we’ve had some really great times on roller coasters in the past. Still other attitudes are learned via the media (Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2003; Levina, Waldo, & Fitzgerald, 2000) or through our interactions with friends (Poteat, 2007). Some of our attitudes are shared by others (most of us like sugar, fear snakes, and are disgusted by cockroaches), whereas other attitudes—such as our preferences for different styles of music or art—are more individualized.

Table 5.1 “Heritability of Some Attitudes” shows some of the attitudes that have been found to be the most highly heritable (i.e. most strongly determined by genetic variation among people). These attitudes form earlier and are stronger and more resistant to change than others (Bourgeois, 2002), although it is not yet known why some attitudes are more genetically determined than are others.

Table 5.1 Heritability of Some Attitudes

| Attitude | Heritability |

|---|---|

| Abortion on demand | 0.54 |

| Roller coaster rides | 0.52 |

| Death penalty for murder | 0.5 |

| Open-door immigration | 0.46 |

| Organized religion | 0.45 |

| Doing athletic activities | 0.44 |

| Voluntary euthanasia | 0.44 |

| Capitalism | 0.39 |

| Playing chess | 0.38 |

| Reading books | 0.37 |

| Exercising | 0.36 |

| Education | 0.32 |

| Big parties | 0.32 |

| Smoking | 0.31 |

| Being the center of attention | 0.28 |

| Getting along well with other people | 0.28 |

| Wearing clothes that draw attention | 0.24 |

| Sweets | 0.22 |

| Public speaking | 0.2 |

| Castration as punishment for sex crimes | 0.17 |

| Loud music | 0.11 |

| Looking my best at all times | 0.1 |

| Doing crossword puzzles | 0.02 |

| Separate roles for men and women | 0 |

| Making racial discrimination illegal | 0 |

| Playing organized sports | 0 |

| Playing bingo | 0 |

| Easy access to birth control | 0 |

| Being the leader of groups | 0 |

| Being assertive | 0 |

| Ranked from most heritable to least heritable. Data are from Olson, Vernon, Harris, and Jang (2001). | |

Our attitudes are made up of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. Consider my own attitude toward chocolate ice cream, which is very positive and always has been, as far as I can remember.

In terms of affect:

I LOVE it!

In terms of behavior:

I frequently eat chocolate ice cream.

In terms of cognitions:

Chocolate ice cream has a smooth texture and a rich, strong taste.

My attitude toward chocolate ice cream is composed of affect, behavior, and cognition.

Although most attitudes are determined by cognition, affect, and behavior, there is nevertheless variability in this regard across people and across attitudes. Some attitudes are more likely to be based on beliefs, some more likely to be based on feelings, and some more likely to be based on behaviors. I would say that my attitude toward chocolate ice cream is in large part determined by affect—although I can describe its taste, mostly I just like it. My attitudes toward my Toyota Corolla and my home air conditioner, on the other hand, are more cognitive. I don’t really like them so much as I admire their positive features (the Toyota gets good gas mileage and the air conditioner keeps me cool on hot summer days). Still other of my attitudes are based more on behavior—I feel like I’ve learned to like my neighbors because I’ve done favors for them over the years (which they have returned) and these helpful behaviors on my part have, at least in part, led me to develop a positive attitude toward them.

Different people may hold attitudes toward the same attitude object for different reasons. Some people voted for Barack Obama in the 2008 elections because they like his policies (“he’s working for the middle class”; “he wants to increase automobile fuel efficiency”), whereas others voted for (or against) him because they just liked (or disliked) him. Although you might think that cognition would be more important in this regard, political scientists have shown that many voting decisions are made primarily on the basis of affect. Indeed, it is fair to say that the affective component of attitudes is generally the strongest and most important (Abelson, Kinder, Peters, & Fiske, 1981; Stangor, Sullivan, & Ford, 1991).

Human beings hold attitudes because they are useful. Particularly, our attitudes enable us to determine, often very quickly and effortlessly, which behaviors to engage in, which people to approach or avoid, and even which products to buy (Duckworth, Bargh, Garcia, & Chaiken, 2002; Maio & Olson, 2000). You can imagine that making quick decisions about what to avoid

snake = bad ⟶ run away

or to approach

blueberries = good ⟶ eat

has had substantial value in our evolutionary experience.

Because attitudes are evaluations, they can be assessed using any of the normal measuring techniques used by social psychologists (Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010). Attitudes are frequently assessed using self-report measures, but they can also be assessed more indirectly using measures of arousal and facial expressions (Mendes, 2008) as well as implicit measures of cognition, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Attitudes can also be seen in the brain by using neuroimaging techniques. This research has found that our attitudes, like most of our social knowledge, are stored primarily in the prefrontal cortex but that the amygdala is important in emotional attitudes, particularly those associated with fear (Cunningham, Raye, & Johnson, 2004; Cunningham & Zelazo, 2007; van den Bos, McClure, Harris, Fiske, & Cohen, 2007). Attitudes can be activated extremely quickly—often within one fifth of a second after we see an attitude object (Handy, Smilek, Geiger, Liu, & Schooler, 2010).

Some Attitudes Are Stronger Than Others

Some attitudes are more important than others, because they are more useful to us and thus have more impact on our daily lives. The importance of an attitude, as assessed by how quickly it comes to mind, is known as attitude strength (Fazio, 1990; Fazio, 1995; Krosnick & Petty, 1995). Some of our attitudes are strong attitudes, in the sense that we find them important, hold them with confidence, do not change them very much, and use them frequently to guide our actions. These strong attitudes may guide our actions completely out of our awareness (Ferguson, Bargh, & Nayak, 2005).

Other attitudes are weaker and have little influence on our actions. For instance, John Bargh and his colleagues (Bargh, Chaiken, Raymond, & Hymes, 1996) found that people could express attitudes toward nonsense words such as juvalamu (which people liked) and chakaka (which they did not like). The researchers also found that these attitudes were very weak. On the other hand, the heavy voter turnout for Barack Obama in the 2008 elections was probably because many of his supporters had strong positive attitudes about him.

Strong attitudes are attitudes that are more cognitively accessible—they come to mind quickly, regularly, and easily. We can easily measure attitude strength by assessing how quickly our attitudes are activated when we are exposed to the attitude object. If we can state our attitude quickly, without much thought, then it is a strong one. If we are unsure about our attitude and need to think about it for a while before stating our opinion, the attitude is weak.

Attitudes become stronger when we have direct positive or negative experiences with the attitude object, and particularly if those experiences have been in strong positive or negative contexts. Russell Fazio and his colleagues (Fazio, Powell, & Herr, 1983) had people either work on some puzzles or watch other people work on the same puzzles. Although the people who watched ended up either liking or disliking the puzzles as much as the people who actually worked on them, Fazio found that attitudes, as assessed by reaction time measures, were stronger (in the sense of being expressed quickly) for the people who had directly experienced the puzzles.

Because attitude strength is determined by cognitive accessibility, it is possible to make attitudes stronger by increasing the accessibility of the attitude. This can be done directly by having people think about, express, or discuss their attitudes with others. After people think about their attitudes, talk about them, or just say them out loud, the attitudes they have expressed become stronger (Downing, Judd, & Brauer, 1992; Tesser, Martin, & Mendolia, 1995). Because attitudes are linked to the self-concept, they also become stronger when they are activated along with the self-concept. When we are looking into a mirror or sitting in front of a TV camera, our attitudes are activated and we are then more likely to act on them (Beaman, Klentz, Diener, & Svanum, 1979).

Attitudes are also stronger when the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition all line up. As an example, many people’s attitude toward their own nation is universally positive. They have strong positive feelings about their country, many positive thoughts about it, and tend to engage in behaviors that support it. Other attitudes are less strong because the affective, cognitive, and behavioral components are each somewhat different (Thompson, Zanna, & Griffin, 1995). My affect toward chocolate ice cream is positive—I like it a lot. On the other hand, my cognitions are more negative—I know that eating too much ice cream can make me fat and that it is bad for my coronary arteries. And even though I love chocolate ice cream, I don’t eat some every time I get a chance. These inconsistencies among the components of my attitude make it less strong than it would be if all the components lined up together.

When Do Our Attitudes Guide Our Behavior?

Social psychologists (as well as advertisers, marketers, and politicians) are particularly interested in the behavioral aspect of attitudes. Because it is normal that the ABCs of our attitudes are at least somewhat consistent, our behavior tends to follow from our affect and cognition. If I determine that you have more positive cognitions about and more positive affect toward Cheerios than Frosted Flakes, then I will naturally predict (and probably be correct when I do so) that you’ll be more likely to buy Cheerios than Frosted Flakes when you go to the market. Furthermore, if I can do something to make your thoughts or feelings toward Frosted Flakes more positive, then your likelihood of buying that cereal instead of the other will also increase.

The principle of attitude consistency (that for any given attitude object, the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition are normally in line with each other) thus predicts that our attitudes (for instance, as measured via a self-report measure) are likely to guide behavior. Supporting this idea, meta-analyses have found that there is a significant and substantial positive correlation among the different components of attitudes, and that attitudes expressed on self-report measures do predict behavior (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006).

Although there is generally consistency between attitudes and behavior, the relationship is stronger in certain situations, for certain people, and for certain attitudes (Wicker, 1969). The theory of planned behavior, developed by Martin Fishbein and Izek Ajzen (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), outlined many of the important variables that affected the attitude-behavior relationship, and some of these factors are summarized in the list that follows this paragraph. It may not surprise you to hear that attitudes that are strong, in the sense that they are expressed quickly and confidently, predict our behavior better than do weak attitudes (Fazio, Powell, & Williams, 1989; Glasman & Albarracín, 2006). For example, Farc and Sagarin (2009) found that people who could more quickly complete questionnaires about their attitudes toward the politicians George Bush and John Kerry were also more likely to vote for the candidate that they had more positive attitudes toward in the 2004 presidential elections. The relationship between the responses on the questionnaires and voting behavior was weaker for those who completed the items more slowly.

- When attitudes are strong, rather than weak

- When we have a strong intention to perform the behavior

- When the attitude and the behavior both occur in similar social situations

- When the same components of the attitude (either affect or cognition) are accessible when the attitude is assessed and when the behavior is performed

- When the attitudes are measured at a specific, rather than a general, level

- For low self-monitors (rather than for high self-monitors)

Attitudes only predict behaviors well under certain conditions and for some people. The preceding list summarizes the factors that create a strong attitude-behavior relationship.

People who have strong attitudes toward an attitude object are also likely to have strong intentions to act on their attitudes, and the intention to engage in an activity is a strong predictor of behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Imagine for a moment that your friend Sharina is trying to decide whether to recycle her used laptop batteries or just throw them away. We know that her attitude toward recycling is positive—she thinks she should do it—but we also know that recycling takes work. It’s much easier to just throw the batteries away. Only if Sharina has a strong attitude toward recycling will she then have the necessary strong intentions to engage in the behavior that will make her recycle her batteries even when it is difficult to do.

The match between the social situations in which the attitudes are expressed and the behaviors are engaged in also matters, such that there is a greater attitude-behavior correlation when the social situations match. Imagine for a minute the case of Magritte, a 16-year-old high school student. Magritte tells her parents that she hates the idea of smoking cigarettes. Magritte’s negative attitude toward smoking seems to be a strong one because she’s thought a lot about it—she believes that cigarettes are dirty, expensive, and unhealthy. But how sure are you that Magritte’s attitude will predict her behavior? Would you be willing to bet that she’d never try smoking when she’s out with her friends?

You can see that the problem here is that Magritte’s attitude is being expressed in one social situation (when she is with her parents) whereas the behavior (trying a cigarette) is going to occur in a very different social situation (when she is out with her friends). The relevant social norms are of course much different in the two situations. Magritte’s friends might be able to convince her to try smoking, despite her initial negative attitude, when they entice her with peer pressure. Behaviors are more likely to be consistent with attitudes when the social situation in which the behavior occurs is similar to the situation in which the attitude is expressed (Ajzen, 1991; LaPiere, 1936).

Research Focus

Attitude-Behavior Consistency

Another variable that has an important influence on attitude-behavior consistency is the current cognitive accessibility of the underlying affective and cognitive components of the attitude. For example, if we assess the attitude in a situation in which people are thinking primarily about the attitude object in cognitive terms, and yet the behavior is performed in a situation in which the affective components of the attitude are more accessible, then the attitude-behavior relationship will be weak. Wilson and Schooler (1991) showed a similar type of effect by first choosing attitudes that they expected would be primarily determined by affect—attitudes toward five different types of strawberry jam. Then they asked a sample of college students to taste each of the jams. While they were tasting, one-half of the participants were instructed to think about the cognitive aspects of their attitudes to these jams—that is, to focus on the reasons they held their attitudes, whereas the other half of the participants were not given these instructions. Then all the students completed measures of their attitudes toward each of the jams.

Wilson and his colleagues then assessed the extent to which the attitudes expressed by the students correlated with taste ratings of the five jams as indicated by experts at Consumer Reports. They found that the attitudes expressed by the students correlated significantly higher with the expert ratings for the participants who had not listed their cognitions first. Wilson and his colleagues argued that this occurred because our liking of jams is primarily affectively determined—we either like them or we don’t. And the students who simply rated the jams used their feelings to make their judgments. On the other hand, the students who were asked to list their thoughts about the jams had some extra information to use in making their judgments, but it was information that was not actually useful. Therefore, when these students used their thoughts about the jam to make the judgments, their judgments were less valid.

MacDonald, Zanna, and Fong (1996) showed male college students a video of two other college students, Mike and Rebecca, who were out on a date. However, according to random assignment to conditions, half of the men were shown the video while sober and the other half viewed the video after they had had several alcoholic drinks. In the video, Mike and Rebecca go to the campus bar and drink and dance. They then go to Rebecca’s room, where they end up kissing passionately. Mike says that he doesn’t have any condoms, but Rebecca says that she is on the pill.

At this point the film clip ends, and the male participants are asked about their likely behaviors if they had been Mike. Although all men indicated that having unprotected sex in this situation was foolish and irresponsible, the men who had been drinking alcohol were more likely to indicate that they would engage in sexual intercourse with Rebecca even without a condom. One interpretation of this study is that sexual behavior is determined by both cognitive factors (“I know that it is important to practice safe sex and so I should use a condom”) and affective factors (“sex is enjoyable, I don’t want to wait”). When the students were intoxicated at the time the behavior was to be performed, it seems likely the affective component of the attitude was a more important determinant of behavior than was the cognitive component.

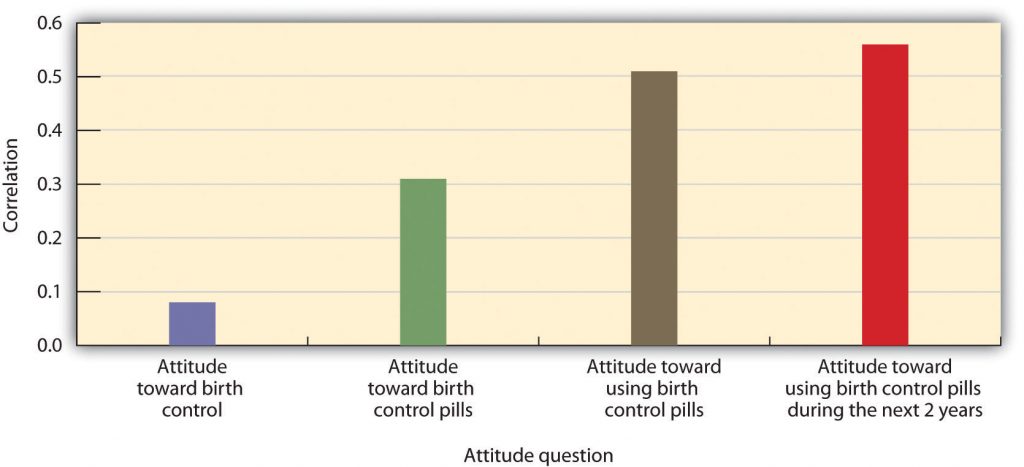

One other type of “match” that has an important influence on the attitude-behavior relationship concerns how we measure the attitude and behavior. Attitudes predict behavior better when the attitude is measured at a level that is similar to the behavior to be predicted. Normally, the behavior is specific, so it is better to measure the attitude at a specific level too. For instance, if we measure cognitions at a very general level (“do you think it is important to use condoms?”; “are you a religious person?”) we will not be as successful at predicting actual behaviors as we will be if we ask the question more specifically, at the level of behavior we are interested in predicting (“do you think you will use a condom the next time you have sex?”; “how frequently do you expect to attend church in the next month?”). In general, more specific questions are better predictors of specific behaviors, and thus if we wish to accurately predict behaviors, we should remember to attempt to measure specific attitudes. One example of this principle is shown in Figure 5.1 “Predicting Behavior From Specific and Nonspecific Attitude Measures”. Davidson and Jaccard (1979) found that they were much better able to predict whether women actually used birth control when they assessed the attitude at a more specific level.

Figure 5.1 Predicting Behavior From Specific and Nonspecific Attitude Measures

Attitudes also predict behavior better for some people than for others. Self-monitoring refers to individual differences in the tendency to attend to social cues and to adjust one’s behavior to one’s social environment. To return to our example of Magritte, you might wonder whether she is the type of person who is likely to be persuaded by peer pressure because she is particularly concerned with being liked by others. If she is, then she’s probably more likely to want to fit in with whatever her friends are doing, and she might try a cigarette if her friends offer her one. On the other hand, if Magritte is not particularly concerned about following the social norms of her friends, then she’ll more likely be able to resist the persuasion. High self-monitors are those who tend to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked; low self-monitors are those who are less likely to do so. You can see that, because they allow the social situation to influence their behaviors, the relationship between attitudes and behavior will be weaker for high self-monitors than it is for low self-monitors (Kraus, 1995).

Key Takeaways

- The term attitude refers to our relatively enduring evaluation of an attitude object.

- Our attitudes are inherited and also learned through direct and indirect experiences with the attitude objects.

- Some attitudes are more likely to be based on beliefs, some more likely to be based on feelings, and some more likely to be based on behaviors.

- Strong attitudes are important in the sense that we hold them with confidence, we do not change them very much, and we use them frequently to guide our actions.

- Although there is a general consistency between attitudes and behavior, the relationship is stronger in some situations than in others, for some measurements than for others, and for some people than for others.

Changing Attitudes Through Persuasion

Learning Objectives

- Outline how persuasion is determined by the choice of effective communicators and effective messages.

- Review the conditions under which attitudes are best changed using spontaneous versus thoughtful strategies.

- Summarize the variables that make us more or less resistant to persuasive appeals.

Every day we are bombarded by advertisements of every sort. The goal of these ads is to sell us cars, computers, video games, clothes, and even political candidates. The ads appear on billboards, website popup ads, TV infomercials, and…well, you name it! It’s been estimated that the average American child views over 40,000 TV commercials every year and that over $400 billion is spent annually on advertising worldwide (Strasburger, 2001).

There is substantial evidence that advertising is effective in changing attitudes. After the R. J. Reynolds Company started airing its Joe Camel ads for cigarettes on TV in the 1980s, Camel cigarettes’ share of sales among children increased dramatically. But persuasion can also have more positive outcomes. Persuasion is used to encourage people to donate to charitable causes, to volunteer to give blood, and to engage in healthy behaviors. The dramatic decrease in cigarette smoking (from about half of the U.S. population who smoked in 1970 to only about a quarter who smoke today) is due in large part to effective advertising campaigns.

Section 3.2 “Emotions, Stress, and Well-Being” considers how we can change people’s attitudes. If you are interested in learning how to persuade others, you may well get some ideas in this regard. If you think that advertisers and marketers have too much influence, then this section will help you understand how to resist such attempts at persuasion. Following the approach used by some of the earliest social psychologists and that still forms the basis of thinking about the power of communication, we will consider which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients (Hovland, Lumsdaine, & Sheffield (1949).

Choosing Effective Communicators

In order to be effective persuaders, we must first get people’s attention, then send an effective message to them, and then ensure that they process the message in the way we would like them to. Furthermore, to accomplish these goals, persuaders must take into consideration the cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of their methods. Persuaders also must understand how the communication they are presenting relates to the message recipient—his or her motivations, desires, and goals.

Research has demonstrated that the same message will be more effective if is delivered by a more persuasive communicator. In general we can say that communicators are more effective when they help their recipients feel good about themselves—that is, by appealing to self-concern. For instance, attractive communicators are frequently more effective persuaders than are unattractive communicators. Attractive communicators create a positive association with the product they are trying to sell and put us in a good mood, which makes us more likely to accept their messages. And as the many marketers who include free gifts, such as mailing labels or small toys, in their requests for charitable donations well know, we are more likely to respond to communicators who offer us something personally beneficial.

We’re also more persuaded by people who are similar to us in terms of opinions and values than by those whom we perceive as being different. This is of course why advertisements targeted at teenagers frequently use teenagers to present the message, and why advertisements targeted at the elderly use older communicators.

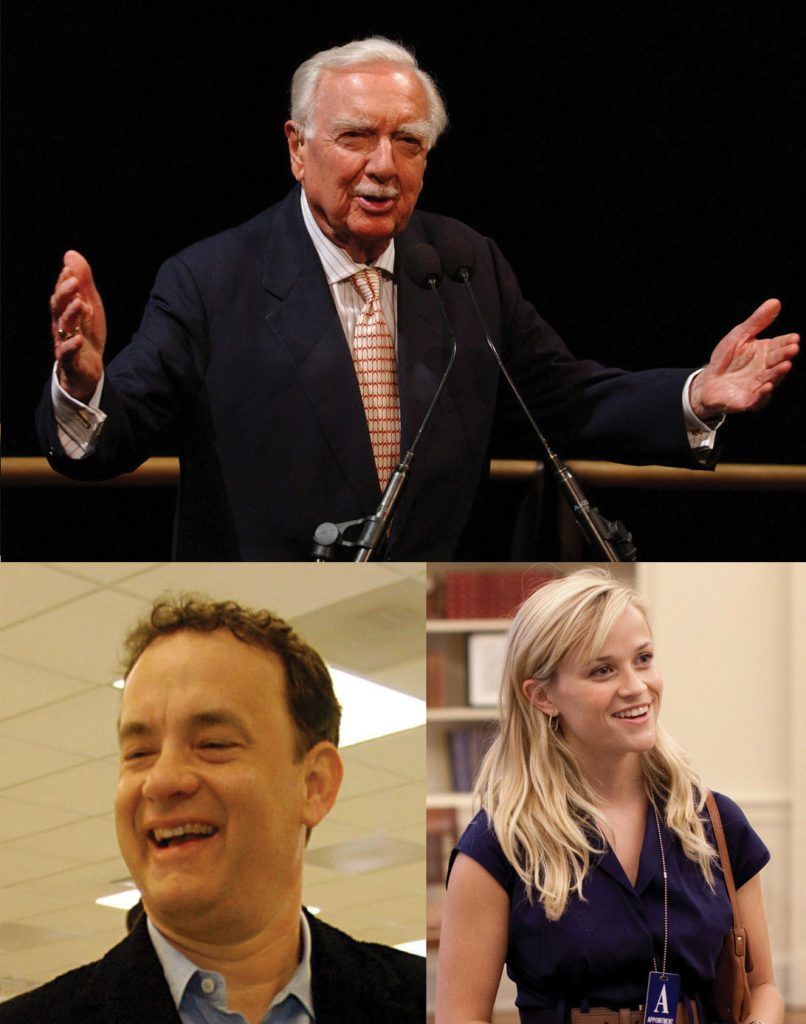

When communicators are perceived as attractive and similar to us, we tend to like them. And we also tend to trust the people that we like. The success of Tupperware parties, in which friends get together to buy products from other friends, may be due more to the fact that people like the “salesperson” than to the nature of the product. People such as the newscaster Walter Cronkite and the film stars Tom Hanks and Reese Witherspoon have been used as communicators for products in part because we see them as trustworthy and thus likely to present an unbiased message. Trustworthy communicators are effective because they allow us to feel good about ourselves when we accept their message, often without critically evaluating its content (Priester & Petty, 2003).

Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Expert communicators may sometimes be perceived as trustworthy because they know a lot about the product they are selling. When a doctor recommends that we take a particular drug, we are likely to be influenced because we know that he or she has expertise about the effectiveness of drugs. It is no surprise that advertisers use race car drivers to sell cars and basketball players to sell athletic shoes.

Although expertise comes in part from having knowledge, it can also be communicated by how one presents a message. Communicators who speak confidently, quickly, and in a straightforward way are seen as more expert than those who speak in a more hesitating and slower manner. Taking regular speech and speeding it up by deleting very small segments of it, so that it sounds the same but actually goes faster, makes the same communication more persuasive (MacLachlan & Siegel, 1980; Moore, Hausknecht, & Thamodaran, 1986). This is probably in part because faster speech makes the communicator seem more like an expert but also because faster speech reduces the listener’s ability to come up with counterarguments as he or she listens to the message (Megehee, Dobie, & Grant, 2003). Effective speakers frequently use this technique, and some of the best persuaders are those who speak quickly.

Although expert communicators are expected to know a lot about the product they are endorsing, they may not be seen as trustworthy if their statements seem to be influenced by external causes. People who are seen to be arguing in their own self-interest (for instance, an expert witness who is paid by the lawyers in a case or a celebrity who is paid for her endorsement of a product) may be ineffective because we may discount their communications (Eagly, Wood, & Chaiken, 1978; Wood & Eagly, 1981). On the other hand, when a person presents a message that goes against external causes, for instance by arguing in favor of an opinion to a person who is known to disagree with it, we see the internal states (that the individual really believes in the message he or she is expressing) as even more powerful.

Communicators also may be seen as biased if they present only one side of an issue while completely ignoring the potential problems or counterarguments to the message. In these cases people who are informed about both sides of the topic may see the communicator as attempting to unfairly influence them.

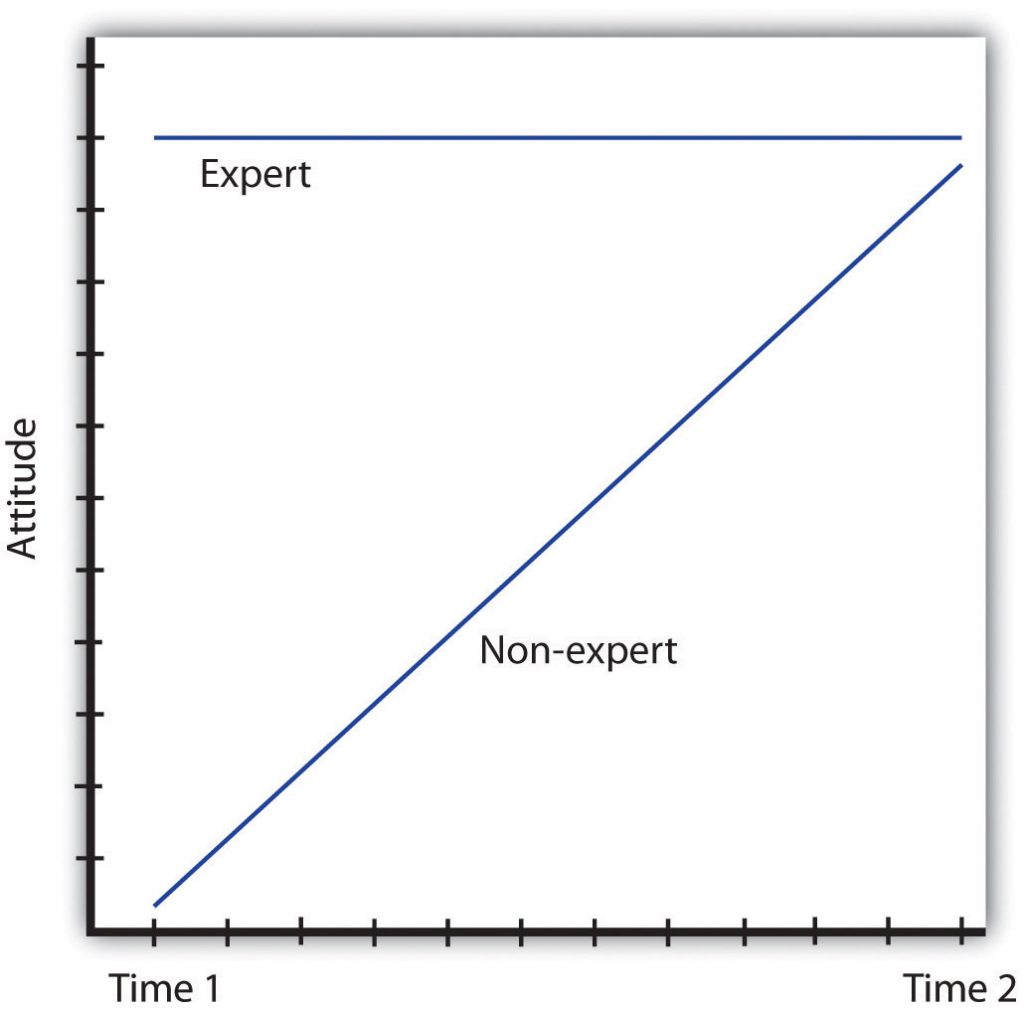

Although we are generally very aware of the potential that communicators may deliver messages that are inaccurate or designed to influence us, and we are able to discount messages that come from sources that we do not view as trustworthy, there is one interesting situation in which we may be fooled by communicators. This occurs when a message is presented by someone that we perceive as untrustworthy. When we first hear that person’s communication we appropriately discount it and it therefore has little influence on our opinions. However, over time there is a tendency to remember the content of a communication to a greater extent than we remember the source of the communication. As a result, we may forget over time to discount the remembered message. This attitude change that occurs over time is known as the sleeper effect (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Figure 5.2 The Sleeper Effect

Perhaps you’ve experienced the sleeper effect. Once, I told my friends a story that I had read about one of my favorite movie stars. Only later did I remember that I had read the story while I was waiting in the supermarket checkout line, and that I had read it in the National Enquirer! I knew that the story was probably false because the newspaper is considered unreliable, but I had initially forgotten to discount that fact because I did not remember the source of the information. The sleeper effect is diagrammed in Figure 5.2 “The Sleeper Effect”.

Creating Effective Communications

Once we have chosen a communicator, the next step is to determine what type of message we should have him or her deliver. Neither social psychologists nor advertisers are so naïve as to think that simply presenting a strong message is sufficient. No matter how good the message is, it will not be effective unless people pay attention to it, understand it, accept it, and incorporate it into their self-concept. This is why we attempt to choose good communicators to present our ads in the first place, and why we tailor our communications to get people to process them the way we want them to.

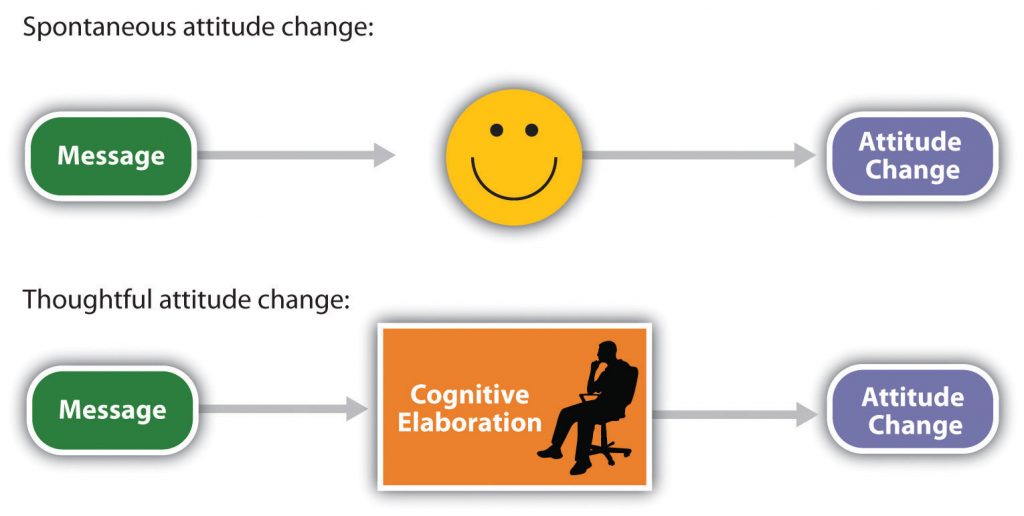

Figure 5.3

The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously (other terms for this include peripherally or heuristically—Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Petty & Wegener, 1999) or thoughtfully (other terms for this include centrally or systematically). Spontaneous processing is direct, quick, and often involves affective responses to the message. Thoughtful processing, on the other hand, is more controlled and involves a more careful cognitive elaboration of the meaning of the message (Figure 5.3). The route that we take when we process a communication is important in determining whether or not a particular message changes attitudes.

Spontaneous Message Processing

Because we are bombarded with so many persuasive messages—and because we do not have the time, resources, or interest to process every message fully—we frequently process messages spontaneously. In these cases, if we are influenced by the communication at all, it is likely that it is the relatively unimportant characteristics of the advertisement, such as the likeability or attractiveness of the communicator or the music playing in the ad, that will influence us.

If we find the communicator cute, if the music in the ad puts us in a good mood, or if it appears that other people around us like the ad, then we may simply accept the message without thinking about it very much (Giner-Sorolla & Chaiken, 1997). In these cases, we engage in spontaneous message processing, in which we accept a persuasion attempt because we focus on whatever is most obvious or enjoyable, without much attention to the message itself. Shelley Chaiken (1980) found that students who were not highly involved in a topic, because it did not affect them personally, were more persuaded by a likeable communicator than by an unlikeable one, regardless of whether the communicator presented a good argument for the topic or a poor one. On the other hand, students who were more involved in the decision were more persuaded by the better than by the poorer message, regardless of whether the communicator was likeable or not—they were not fooled by the likeability of the communicator.

You might be able to think of some advertisements that are likely to be successful because they create spontaneous processing of the message by basing their persuasive attempts around creating emotional responses in the listeners. In these cases the advertisers use associational learning to associate the positive features of the ad with the product. Television commercials are often humorous, and automobile ads frequently feature beautiful people having fun driving beautiful cars. The slogans “The joy of cola!” “Coke adds life!” and “Be a Pepper!” are good ads in part because they successfully create positive affect in the listener.

In some cases emotional ads may be effective because they lead us to watch or listen to the ad rather than simply change the channel or doing something else. The clever and funny TV ads that are shown during the Super Bowl broadcast every year are likely to be effective because we watch them, remember them, and talk about them with others. In this case the positive affect makes the ads more salient, causing them to grab our attention. But emotional ads also take advantage of the role of affect in information processing. We tend to like things more when we are in good moods, and—because positive affect indicates that things are OK—we process information less carefully when we are in good moods. Thus the spontaneous approach to persuasion is particularly effective when people are happy (Sinclair, Mark, & Clore, 1994), and advertisers try to take advantage of this fact.

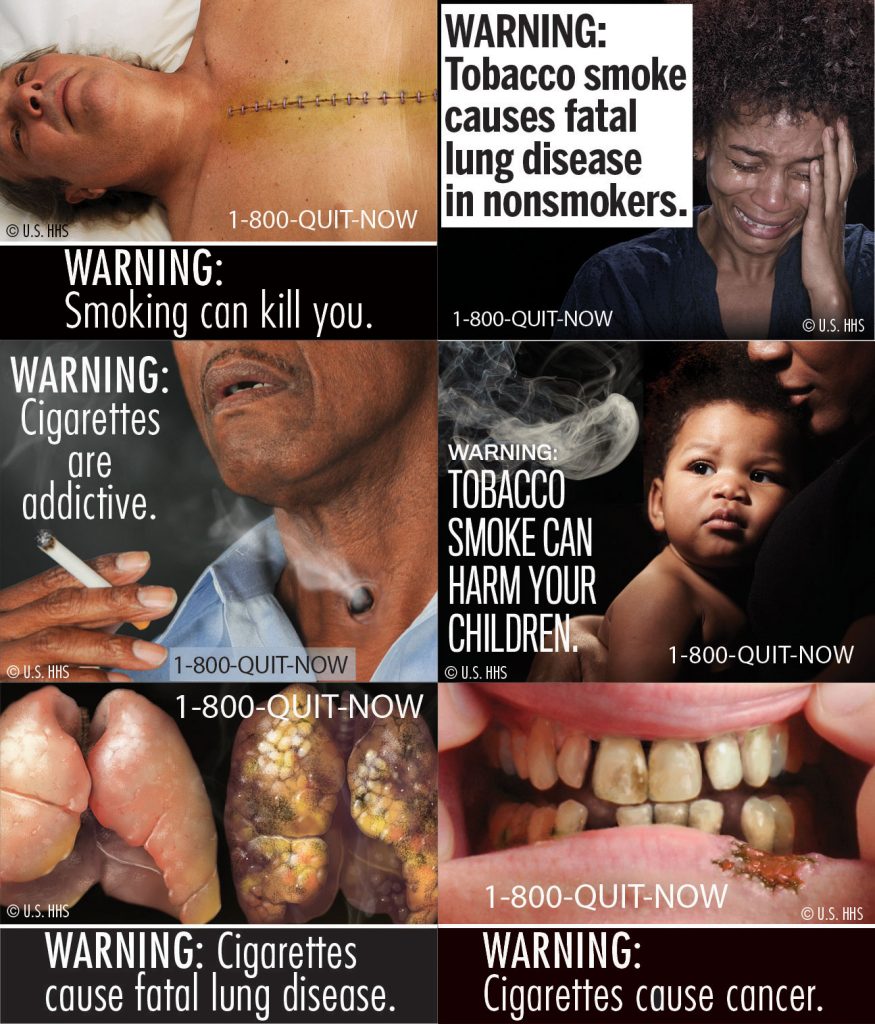

Another type of ad that is based on emotional responses is the one that uses fear appeals, such as ads that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to decrease smoking. By and large, fearful messages are persuasive (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000). Again, this is due in part to the fact that the emotional aspects of the ads make them salient and lead us to attend to and remember them. And fearful ads may also be framed in a way that leads us to focus on the salient negative outcomes that have occurred for one particular individual. When we see an image of a person who is jailed for drug use, we may be able to empathize with that person and imagine how we would feel if it happened to us. Thus this ad may be more effective than more “statistical” ads stating the base rates of the number of people who are jailed for drug use every year.

Fearful ads also focus on self-concern, and advertisements that are framed in a way that suggests that a behavior will harm the self are more effective than the same messages that are framed more positively. Banks, Salovey, Greener, and Rothman (1995) found that a message that emphasized the negative aspects of not getting a breast cancer screening mammogram (“not getting a mammogram can cost you your life”) was more effective than a similar message that emphasized the positive aspects (“getting a mammogram can save your life”) in getting women to have a mammogram over the next year. These findings are consistent with the general idea that the brain responds more strongly to negative affect than it does to positive affect (Ito, Larsen, Smith, & Cacioppo, 1998).

Although laboratory studies generally find that fearful messages are effective in persuasion, they have some problems that may make them less useful in real-world advertising campaigns (Hastings, Stead, & Webb, 2004). Fearful messages may create a lot of anxiety and therefore turn people off to the message (Shehryar & Hunt, 2005). For instance, people who know that smoking cigarettes is dangerous but who cannot seem to quit may experience particular anxiety about their smoking behaviors. Fear messages are more effective when people feel that they know how to rectify the problem, have the ability to actually do so, and take responsibility for the change. Without some feelings of self-efficacy, people do not know how to respond to the fear (Aspinwall, Kemeny, Taylor, & Schneider, 1991). Thus if you want to scare people into changing their behavior, it may be helpful if you also give them some ideas about how to do so, so that they feel like they have the ability to take action to make the changes (Passyn & Sujan, 2006).

Thoughtful Message Processing

When we process messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process messages thoughtfully, cognition prevails. When we care about the topic, find it relevant, and have plenty of time to spend thinking about the communication, we are likely to process the message more deliberatively, carefully, and thoughtfully (Petty & Briñol, 2008). In this case we elaborate on the communication by considering the pros and cons of the message and questioning the validity of the communicator and the message. Thoughtful message processing occurs when we think about how the message relates to our own beliefs and goals and involves our careful consideration of whether the persuasion attempt is valid or invalid.

When an advertiser presents a message that he or she hopes will be processed thoughtfully, the goal is to create positive cognitions about the attitude object in the listener. The communicator mentions positive features and characteristics of the product and at the same time attempts to downplay the negative characteristics. When people are asked to list their thoughts about a product while they are listening to, or right after they hear, a message, those who list more positive thoughts also express more positive attitudes toward the product than do those who list more negative thoughts (Petty & Briñol, 2008). Because the thoughtful processing of the message bolsters the attitude, thoughtful processing helps us develop strong attitudes, which are therefore resistant to counterpersuasion (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981).

Which Route Do We Take: Thoughtful or Spontaneous?

Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, but it is important to know which is likely to be better in which situation and for which people. When we can motivate people to process our message carefully and thoughtfully, then we are going to be able to present our strong and persuasive arguments with the expectation that our audience will attend to them. If we can get the listener to process these strong arguments thoughtfully, then the attitude change will likely be strong and long lasting. On the other hand, when we expect our listeners to process only spontaneously—for instance, if they don’t care too much about our message or if they are busy doing other things—then we do not need to worry so much about the content of the message itself; even a weak (but interesting) message can be effective in this case. Successful advertisers tailor their messages to fit the expected characteristics of their audiences.

In addition to being motivated to process the message, we must also have the ability to do so. If the message is too complex to understand, we may rely on spontaneous cues, such as the perceived trustworthiness or expertise of the communicator (Hafer, Reynolds, & Obertynski, 1996), and ignore the content of the message. When experts are used to attempt to persuade people—for instance, in complex jury trials—the messages that these experts give may be very difficult to understand. In these cases the jury members may rely on the perceived expertise of the communicator rather than his or her message, being persuaded in a relatively spontaneous way. In other cases we may not be able to process the information thoughtfully because we are distracted or tired—in these cases even weak messages can be effective, again because we process them spontaneously (Petty, Wells & Brock, 1976).

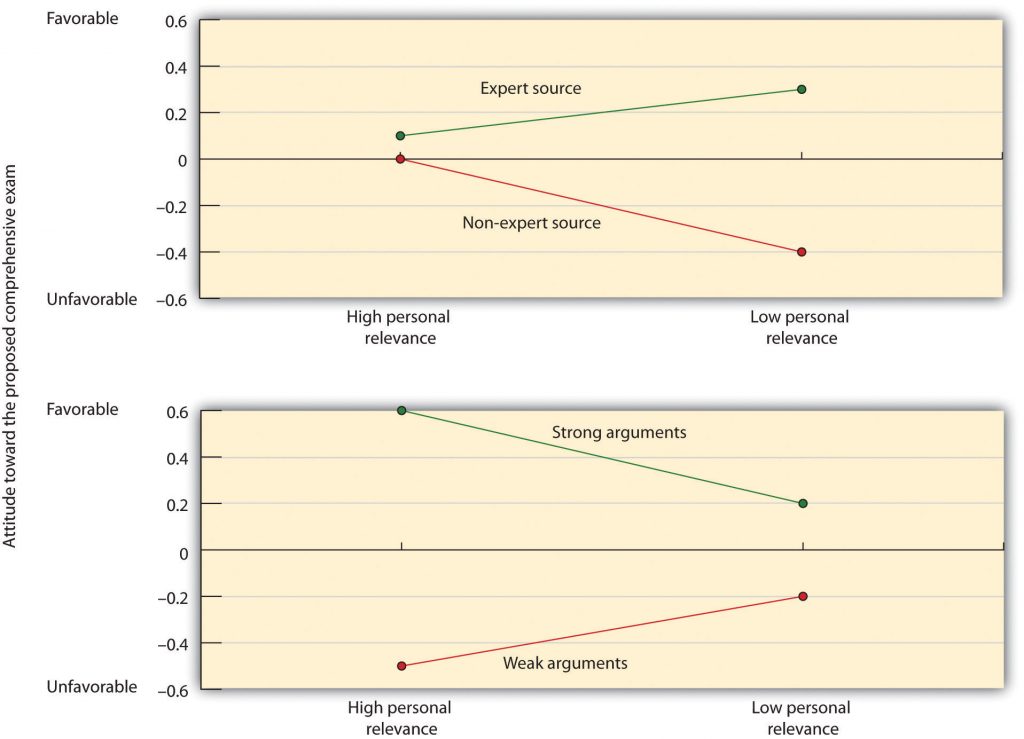

Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981) showed how different motivations may lead to either spontaneous or thoughtful processing. In their research, college students heard a message suggesting that the administration at their college was proposing to institute a new comprehensive exam that all students would need to pass in order to graduate and then rated the degree to which they were favorable toward the idea. The researchers manipulated three independent variables:

- Message strength. The message contained either strong arguments (persuasive data and statistics about the positive effects of the exams at other universities) or weak arguments(relying only on individual quotations and personal opinions).

- Source expertise. The message was supposedly prepared either by an expert source (the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, which was chaired by a professor of education at Princeton University) or by a nonexpert source (a class at a local high school).

- Personal relevance. The students were told either that the new exam would begin before they graduated (high personal relevance) or that it would not begin until after they had already graduated (low personal relevance).

As you can see in Figure 5.4, Petty and his colleagues found two interaction effects. The top panel of the figure shows that the students in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were not particularly influenced by the expertise of the source, whereas the students in the low personal relevance condition (right side) were. On the other hand, as you can see in the bottom panel, the students who were in the high personal relevance condition (left side) were strongly influenced by the quality of the argument, but the low personal involvement students (right side) were not.

These findings fit with the idea that when the issue was important, the students engaged in thoughtful processing of the message itself. When the message was largely irrelevant, they simply used the expertise of the source without bothering to think about the message.

Figure 5.4

Because both thoughtful and spontaneous approaches can be successful, advertising campaigns, such as those used by the Obama presidential campaign, carefully make use of both spontaneous and thoughtful messages. In some cases, the messages showed Obama smiling, shaking hands with people around him, and kissing babies; in other ads Obama was shown presenting his plans for energy efficiency and climate change in more detail.

Preventing Persuasion

To this point we have focused on techniques designed to change attitudes. But it is also useful to develop techniques that prevent attitude change. If you are hoping that Magritte will never puff that first cigarette, then you might be interested in knowing what her parents might be able to do to prevent it from happening.

One approach to improving an individual’s ability to resist persuasion is to help the person create a strong attitude. Strong attitudes are more difficult to change than are weak attitudes, and we are more likely to act on our strong attitudes. This suggests that Magritte’s parents might want help Magritte consider all the reasons that she should not smoke and develop strong negative affect about smoking. As Magritte’s negative thoughts and feelings about smoking become more well-defined and more integrated into the self-concept, they should have a bigger influence on her behavior.

One method of increasing attitude strength involves forewarning: giving people a chance to develop a resistance to persuasion by reminding them that they might someday receive a persuasive message, and allowing them to practice how they will respond to influence attempts (Sagarin & Wood, 2007). Magritte’s parents might want to try the forewarning approach. After the forewarning, when Magritte hears the smoking message from her peers, she may be less influenced by it because she was aware ahead of time that the persuasion would likely occur and had already considered how to resist it.

Forewarning seems to be particularly effective when the message that is expected to follow attacks an attitude that we care a lot about. In these cases the forewarning prepares us for action—we bring up our defenses to maintain our existing beliefs. When we don’t care much about the topic, on the other hand, we may simply change our belief before the appeal actually comes (Wood & Quinn, 2003).

Forewarning can be effective in helping people respond to persuasive messages that they will receive later.

A similar approach is to help build up the cognitive component of the attitude by presenting a weak attack on the existing attitude with the goal of helping the person create counterarguments about a persuasion attempt that is expected to come in the future. Just as an inoculation against the flu gives us a small dose of the influenza virus that helps prevent a bigger attack later, giving Magritte a weak argument to persuade her to smoke cigarettes can help her develop ways to resist the real attempts when they come in the future. This procedure—known as inoculation—involves building up defenses against persuasion by mildly attacking the attitude position (Compton & Pfau, 2005; McGuire, 1961). We would begin by telling Magritte the reasons that her friends might think that she should smoke (for instance, because everyone is doing it and it makes people look “cool”), therefore allowing her to create some new defenses against persuasion. Thinking about the potential arguments that she might receive and preparing the corresponding counterarguments will make the attitude stronger and more resistant to subsequent change attempts.

One difficulty with forewarning and inoculation attempts is that they may boomerang. If we feel that another person—for instance, a person who holds power over us—is attempting to take away our freedom to make our own decisions, we may respond with strong emotion, completely ignore the persuasion attempt, and perhaps even engage in the opposite behavior. Perhaps you can remember a time when you felt like your parents or someone else who had some power over you put too much pressure on you, and you rebelled against them.

The strong emotional response that we experience when we feel that our freedom of choice is being taken away when we expect that we should have choice is known as psychological reactance (Brehm, 1966; Miron & Brehm, 2006). If Magritte’s parents are too directive in their admonitions about not smoking, she may feel that they do not trust her to make her own decisions and are attempting to make them for her. In this case she may experience reactance and become more likely to start smoking. Erceg-Hurn and Steed (2011) found that the graphic warning images that are placed on cigarette packs could create reactance in people who viewed them, potentially reducing the warnings’ effectiveness in convincing people to stop smoking.

Given the extent to which our judgments and behaviors are frequently determined by processes that occur outside of our conscious awareness, you might wonder whether it is possible to persuade people to change their attitudes or to get people to buy products or engage in other behaviors using subliminal advertising. Subliminal advertising occurs when a message, such as an advertisement or another image of a brand, is presented to the consumer without the person being aware that a message has been presented—for instance, by flashing messages quickly in a TV show, an advertisement, or a movie (Theus, 1994).

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

Does Subliminal Advertising Work?

If it were effective, subliminal advertising would have some major advantages for advertisers because it would allow them to promote their product without directly interrupting the consumer’s activity and without the consumer knowing that he or she is being persuaded (Trappey, 1996). People cannot counterargue with, or attempt to avoid being influenced by, messages that they do not know they have received and this may make subliminal advertising particularly effective. Due to fears that people may be influenced to buy products out of their awareness, subliminal advertising has been legally banned in many countries, including Australia, Great Britain, and the United States.

Some research has suggested that subliminal advertising may be effective. Karremans, Stroebe, and Claus (2006) had Dutch college students view a series of computer trials in which a string of letters such as BBBBBBBBB or BBBbBBBBB was presented on the screen and the students were asked to pay attention to whether or not the strings contained a small b. However, immediately before each of the letter strings, the researchers presented either the name of a drink that is popular in Holland (“Lipton Ice”) or a control string containing the same letters as Lipton Ice (“Npeic Tol”). The priming words were presented so quickly (for only about 1/50th of a second) that the participants could not see them.

Then the students were asked to indicate their intention to drink Lipton Ice by answering questions such as “If you would sit on a terrace now, how likely is it that you would order Lipton Ice?” and also to indicate how thirsty they were at this moment. The researchers found that the students who had been exposed to the Lipton Ice primes were significantly more likely to say that they would drink Lipton Ice than were those who had been exposed to the control words, but that this was only true for the participants who said that they were currently thirsty.

On the other hand, other research has not supported the effectiveness of subliminal advertising. Charles Trappey (1996) conducted a meta-analysis in which he combined 23 research studies that had tested the influence of subliminal advertising on consumer choice. The results of his meta-analysis showed that subliminal advertising had a “negligible effect on consumer choice.” Saegert (1987) concluded that “marketing should quit giving subliminal advertising the benefit of the doubt” (p. 107), arguing that the influences of subliminal stimuli are usually so weak that they are normally overshadowed by the person’s own decision making about the behavior.

Even if a subliminal or subtle advertisement is perceived, previous experience with the product or similar products—or even unrelated, more salient stimuli at the moment—may easily overshadow any effect the subliminal message would have had (Moore, 1988). That is, even if we do perceive the “hidden” message, our prior attitudes or our current situation will likely have a stronger influence on our choices, potentially nullifying any effect the subliminal message would have had.

Taken together, the evidence for the effectiveness of subliminal advertising is weak and its effects may be limited to only some people and only some conditions. You probably don’t have to worry too much about being subliminally persuaded in your everyday life even if subliminal ads are allowed in your country. Of course, although subliminal advertising is not that effective, there are plenty of other indirect advertising techniques that are. Many ads for automobiles and alcoholic beverages have sexual connotations, which indirectly (even if not subliminally) associate these positive features with their products. And there are the ever more frequent “product placement” techniques, where images of brands (cars, sodas, electronics, and so forth) are placed on websites and in popular TV shows and movies.

Key Takeaways

- Advertising is effective in changing attitudes, and principles of social psychology can help us understand when and how advertising works.

- Social psychologists study which communicators can deliver the most effective messages to which types of message recipients.

- Communicators are more effective when they help their recipients feel good about themselves. Attractive, similar, trustworthy, and expert communicators are examples of effective communicators.

- Attitude change that occurs over time, particularly when we no longer discount the impact of a low-credibility communicator, is known as the sleeper effect.

- The messages that we deliver may be processed either spontaneously or thoughtfully. When we are processing messages only spontaneously, our feelings are more likely to be important, but when we process the message thoughtfully, cognition prevails.

- Both thoughtful and spontaneous messages can be effective, in different situations and for different people.

- One approach to improving an individual’s ability to resist persuasion is to help the person create a strong attitude. Procedures such as forewarning and inoculation can help increase attitude strength and thus reduce subsequent persuasion.

- Taken together, the evidence for the effectiveness of subliminal advertising is weak, and its effects may be limited to only some people and only some conditions.

Although we might use the term in a different way in our everyday life (“Hey, he’s really got an attitude!”), social psychologists reserve the term attitude to refer to our relatively enduring evaluation of something, where the something is called the attitude object. The attitude object might be a person, a product, or a social group (Albarracín, Johnson, & Zanna, 2005; Wood, 2000). In this section we will consider the nature and strength of attitudes and the conditions under which attitudes best predict our behaviors.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

Attitude

A psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor.

Attitude consistency

For any given attitude object, the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition are normally in line with each other

Attitude object

A person, a product, or a social group

Attitude strength

The importance of an attitude, as assessed by how quickly it comes to mind

Expert communicators

Perceived as trustworthy because they know a lot about the product they are selling

Forewarning

Giving people a chance to develop a resistance to persuasion by reminding them that they might someday receive a persuasive message, and allowing them to practice how they will respond to influence attempts

High self-monitors

Those who tend to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked

Inoculation

Building up defenses against persuasion by mildly attacking the attitude position

Low self-monitors

Those who are less likely to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked

Psychological reactance

A reaction to people, rules, requirements, or offerings that are perceived to limit freedoms.

Self-monitoring

Individual differences in the tendency to attend to social cues and to adjust one’s behavior to one’s social environment

Spontaneous message processing

When we accept a persuasion attempt because we focus on whatever is most obvious or enjoyable, without much attention to the message itself.

Subliminal advertising

Occurs when a message, such as an advertisement or another image of a brand, is presented to the consumer without the person being aware that a message has been presented

Theory of planned behavior

The relationship between attitudes and behavior is stronger in certain situations, for certain people and for certain attitudes

The sleeper effect

Attitude change that occurs over time

Thoughtful message processing

When we think about how the message relates to our own beliefs and goals and involves our careful consideration of whether the persuasion attempt is valid or invalid

References

Abelson, R. P., Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., & Fiske, S. T. (1981). Affective and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 619–630.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (Eds.). (2005). The handbook of attitudes (pp. 223–271). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Banaji, M. R., & Heiphetz, L. (2010). Attitudes. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 353–393). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bargh, J. A., Chaiken, S., Raymond, P., & Hymes, C. (1996). The automatic evaluation effect: Unconditional automatic attitude activation with a pronunciation task. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(1), 104–128.

Beaman, A. L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., & Svanum, S. (1979). Self-awareness and transgression in children: Two field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1835–1846.

Bourgeois, M. J. (2002). Heritability of attitudes constrains dynamic social impact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(8), 1063–1072.

Cunningham, W. A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2007). Attitudes and evaluations: A social cognitive neuroscience perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(3), 97–104.

Cunningham, W. A., Raye, C. L., & Johnson, M. K. (2004). Implicit and explicit evaluation: fMRI correlates of valence, emotional intensity, and control in the processing of attitudes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(10), 1717–1729.

Davidson, A. R., & Jaccard, J. J. (1979). Variables that moderate the attitude-behavior relation: Results of a longitudinal survey. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(8), 1364–1376.

De Houwer, J., Thomas, S., & Baeyens, F. (2001). Association learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 853–869.

Downing, J. W., Judd, C. M., & Brauer, M. (1992). Effects of repeated expressions on attitude extremity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 17–29.

Duckworth, K. L., Bargh, J. A., Garcia, M., & Chaiken, S. (2002). The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychological Science, 13(6), 513–519.

Farc, M.-M., & Sagarin, B. J. (2009). Using attitude strength to predict registration and voting behavior in the 2004 U.S. presidential elections. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31(2), 160–173. doi: 10.1080/01973530902880498.

Fazio, R. H. (1990). The MODE model as an integrative framework. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 75–109.

Fazio, R. H. (1995). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fazio, R. H., Powell, M. C., & Herr, P. M. (1983). Toward a process model of the attitude-behavior relation: Accessing one’s attitude upon mere observation of the attitude object. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(4), 723–735.

Fazio, R. H., Powell, M. C., & Williams, C. J. (1989). The role of attitude accessibility in the attitude-to-behavior process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 280–288.

Ferguson, M. J., Bargh, J. A., & Nayak, D. A. (2005). After-affects: How automatic evaluations influence the interpretation of subsequent, unrelated stimuli. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.05.008.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778–822.

Handy, T. C., Smilek, D., Geiger, L., Liu, C., & Schooler, J. W. (2010). ERP evidence for rapid hedonic evaluation of logos. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(1), 124–138. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21180.

Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Female “thin ideal” media images and boys’ attitudes toward girls. Sex Roles, 49(9–10), 539–544.

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(1), 58–75.

Krosnick, J. A., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Attitude strength: An overview. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 1–24). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

LaPiere, R. T. (1936). Type rationalization of group antipathy. Social Forces, 15, 232–237.

Levina, M., Waldo, C. R., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2000). We’re here, we’re queer, we’re on TV: The effects of visual media on heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(4), 738–758.

MacDonald, T. K., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (1996). Why common sense goes out the window: Effects of alcohol on intentions to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 763–775.

Maio, G. R., & Olson, J. M. (Eds.). (2000). Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mendes, W. B. (2008). Assessing autonomic nervous system reactivity. In E. Harmon-Jones & J. Beer (Eds.), Methods in the neurobiology of social and personality psychology (pp. 118–147). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Olson, J. M., Vernon, P. A., Harris, J. A., & Jang, K. L. (2001). The heritability of attitudes: A study of twins. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 845–860.

Poteat, V. P. (2007). Peer group socialization of homophobic attitudes and behavior during adolescence. Child Development, 78(6), 1830–1842.

Stangor, C., Sullivan, L. A., & Ford, T. E. (1991). Affective and cognitive determinants of prejudice. Social Cognition, 9(4), 359–380.

Tesser, A., Martin, L., & Mendolia, M. (Eds.). (1995). The impact of thought on attitude extremity and attitude-behavior consistency. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Thompson, M. M., Zanna, M. P., & Griffin, D. W. (1995). Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 361–386). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

van den Bos, W., McClure, S. M., Harris, L. T., Fiske, S. T., & Cohen, J. D. (2007). Dissociating affective evaluation and social cognitive processes in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(4), 337–346.

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social Issues, 25(4), 41–78.

Wilson, T. D., & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 181–192.

Wood, W. (2000). Attitude change: Persuasion and social influence. Annual Review of Psychology, 539–570.

Moore, D. L., Hausknecht, D., & Thamodaran, K. (1986). Time compression, response opportunity, and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 85–99.

Moore, T. E. (1988). The case against subliminal manipulation. Psychology and Marketing, 5(4), 297–316.

Passyn, K., & Sujan, M. (2006). Self-accountability emotions and fear appeals: Motivating behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(4), 583–589. doi: 10.1086/500488.

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petty, R. E., & Briñol, P. (2008). Persuasion: From single to multiple to metacognitive processes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 137–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00071.x.

Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1999). The elaboration likelihood model: Current status and controversies. In Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 37–72). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(5), 847–855.

Petty, R. E., Wells, G. L., & Brock, T. C. (1976). Distraction can enhance or reduce yielding to propaganda: Thought disruption versus effort justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(5), 874–884.

Priester, J. R., & Petty, R. E. (2003). The influence of spokesperson trustworthiness on message elaboration, attitude strength, and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(4), 408–421.

Saegert, J. (1987). Why marketing should quit giving subliminal advertising the benefit of the doubt. Psychology and Marketing, 4(2), 107–121.

Sagarin, B. J., & Wood, S. E. (2007). Resistance to influence. In A. R. Pratkanis (Ed.), The science of social influence: Advances and future progress (pp. 321–340). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Shehryar, O., & Hunt, D. M. (2005). A terror management perspective on the persuasiveness of fear appeals. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(4), 275–287. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1504_2.

Sinclair, R. C., Mark, M. M., & Clore, G. L. (1994). Mood-related persuasion depends on (mis)attributions. Social Cognition, 12(4), 309–326.

Strasburger, V. C. (2001). Children and TV advertising: Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22(3), 185–187.

Theus, K. T. (1994). Subliminal advertising and the psychology of processing unconscious stimuli: A review of research. Psychology and Marketing, 11(3), 271–291.

Trappey, C. (1996). A meta-analysis of consumer choice and subliminal advertising. Psychology and Marketing, 13(5), 517–531.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. (1981). Stages in the analysis of persuasive messages: The role of causal attributions and message comprehension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(2), 246–259.

Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2003). Forewarned and forearmed? Two meta-analysis syntheses of forewarnings of influence appeals. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 119–138.

This course makes use of Open Educational Resources. Information on the original source of this chapter can be found below.

Principles of Social Psychology is adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) in 2010 by a publisher who has requested that it and the original author not receive attribution. The chapter which was adapted by Queen’s Psychology was originally adapted and produced by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative.

A psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor.

A person, a product, or a social group

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (Eds.). (2005). The handbook of attitudes (pp. 223–271). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2003). Forewarned and forearmed? Two meta-analysis syntheses of forewarnings of influence appeals. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 119–138.

Olson, J. M., Vernon, P. A., Harris, J. A., & Jang, K. L. (2001). The heritability of attitudes: a study of twins. Journal of personality and social psychology, 80(6), 845.

De Houwer, J., Thomas, S., & Baeyens, F. (2001). Association learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 853–869.

Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Female “thin ideal” media images and boys’ attitudes toward girls. Sex Roles, 49(9–10), 539–544.

Levina, M., Waldo, C. R., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2000). We’re here, we’re queer, we’re on TV: The effects of visual media on heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(4), 738–758.

Poteat, V. P. (2007). Peer group socialization of homophobic attitudes and behavior during adolescence. Child Development, 78(6), 1830–1842.

Bourgeois, M. J. (2002). Heritability of attitudes constrains dynamic social impact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(8), 1063–1072.

Abelson, R. P., Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., & Fiske, S. T. (1981). Affective and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 619–630.

Stangor, C., Sullivan, L. A., & Ford, T. E. (1991). Affective and cognitive determinants of prejudice. Social Cognition, 9(4), 359–380.

Duckworth, K. L., Bargh, J. A., Garcia, M., & Chaiken, S. (2002). The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychological Science, 13(6), 513–519.

Maio, G. R., & Olson, J. M. (Eds.). (2000). Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Banaji, M. R., & Heiphetz, L. (2010). Attitudes. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 353–393). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mendes, W. B. (2008). Assessing autonomic nervous system reactivity. In E. Harmon-Jones & J. Beer (Eds.), Methods in the neurobiology of social and personality psychology (pp. 118–147). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cunningham, W. A., Raye, C. L., & Johnson, M. K. (2004). Implicit and explicit evaluation: fMRI correlates of valence, emotional intensity, and control in the processing of attitudes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(10), 1717–1729.

Cunningham, W. A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2007). Attitudes and evaluations: A social cognitive neuroscience perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(3), 97–104.

van den Bos, W., McClure, S. M., Harris, L. T., Fiske, S. T., & Cohen, J. D. (2007). Dissociating affective evaluation and social cognitive processes in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(4), 337–346.

Handy, T. C., Smilek, D., Geiger, L., Liu, C., & Schooler, J. W. (2010). ERP evidence for rapid hedonic evaluation of logos. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(1), 124–138. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21180.

The importance of an attitude, as assessed by how quickly it comes to mind

Fazio, R. H. (1990). The MODE model as an integrative framework. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 75–109.

Fazio, R. H. (1995). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Krosnick, J. A., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Attitude strength: An overview. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 1–24). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferguson, M. J., Bargh, J. A., & Nayak, D. A. (2005). After-affects: How automatic evaluations influence the interpretation of subsequent, unrelated stimuli. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.05.008.

Bargh, J. A., Chaiken, S., Raymond, P., & Hymes, C. (1996). The automatic evaluation effect: Unconditional automatic attitude activation with a pronunciation task. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(1), 104–128.

Fazio, R. H., Powell, M. C., & Herr, P. M. (1983). Toward a process model of the attitude-behavior relation: Accessing one’s attitude upon mere observation of the attitude object. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(4), 723–735.

Downing, J. W., Judd, C. M., & Brauer, M. (1992). Effects of repeated expressions on attitude extremity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 17–29.

Tesser, A., Martin, L., & Mendolia, M. (Eds.). (1995). The impact of thought on attitude extremity and attitude-behavior consistency. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Beaman, A. L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., & Svanum, S. (1979). Self-awareness and transgression in children: Two field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1835–1846.

Thompson, M. M., Zanna, M. P., & Griffin, D. W. (1995). Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 361–386). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

For any given attitude object, the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition are normally in line with each other

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778–822.

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social Issues, 25(4), 41–78.

The relationship between attitudes and behavior is stronger in certain situations, for certain people and for certain attitudes

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fazio, R. H., Powell, M. C., & Williams, C. J. (1989). The role of attitude accessibility in the attitude-to-behavior process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 280–288.

Farc, M.-M., & Sagarin, B. J. (2009). Using attitude strength to predict registration and voting behavior in the 2004 U.S. presidential elections. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31(2), 160–173. doi: 10.1080/01973530902880498.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

LaPiere, R. T. (1936). Type rationalization of group antipathy. Social Forces, 15, 232–237.

Davidson, A. R., & Jaccard, J. J. (1979). Variables that moderate the attitude-behavior relation: Results of a longitudinal survey. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(8), 1364–1376.

Individual differences in the tendency to attend to social cues and to adjust one’s behavior to one’s social environment

Those who tend to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked

Those who are less likely to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(1), 58–75.