38 Autism: Insights from the Study of the Social Brain

Original chapter by Kevin A. Pelphrey adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

We encourage students to use the “Three-Step Method” for support in their learning. Please find our version of the Three-Step Method, created in collaboration with Queen’s Student Academic Success Services, at the following link: https://sass.queensu.ca/psyc100/

Autistic people can struggle with initiating, maintaining, and understanding social interactions. Social neuroscience is the study of the parts of the brain that support social interactions or the “social brain.” This module provides an overview of autism and focuses on understanding the social brain. Our increasing understanding of the social brain will allow us to better identify the genes associated with autism, and will help us to best support individuals. Because social brain systems emerge in infancy, social neuroscience can help us to understand autism even before the symptoms of autism are clearly present. This is a hopeful time because social brain systems remain malleable well into adulthood and thus open to creative new interventions that are informed by state-of-the-art science.

Learning Objectives

- Know the basic symptoms of autism.

- Distinguish components of the social brain and understand their differences in autism.

- Appreciate how social neuroscience may facilitate the diagnosis of, and supports for, autism.

A personal note from the PSYC100 Teaching Team:

In this course we generally use person-first language when talking about individuals. For example, you will notice the use of person-first language as we talk about mental health diagnoses. Person-first language is generally used to affirm the value of people more so than their label (e.g., person with schizophrenia, not a “schizophrenic”).

This week our content includes autism. Many advocates in the Autism community prefer identity-first language rather than person-first language (e.g., there is a preference for “Autistic” or “Autistic person” being preferred over “person with Autism”). This identity-first language is generally preferred in the Autism community because it recognizes the value and worth of Autistic people – that being Autistic has value. For more on this distinction you can check out a wonderful blog post by the Autistic Self Advocacy Network https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/identity-first-language/

We are grateful to have a diverse student population in PSYC100, and a diverse teaching staff. In a class this size, we want to make it explicit that we respect individuals (you and each other!), and we want to be intentional about recognizing that we each have preferred ways of being acknowledged. Because of this, and because preferred language varies, we use person-first language in this book to reaffirm our commitment to respecting the dignity of individuals. In this chapter, we you will see the use of “Autistic” which differs from our typical practice. This is for the reasons above.

We also want to highlight an important aspect related to language when talking about diagnoses: a diagnosis is not necessarily considered a burden. This means that it is important to avoid language such as “suffers from autism.” Developing a vocabulary that is inclusive and respects the dignity of individuals takes time, practice, and learning from mistakes. It’s okay to make mistakes, as long we are all open to feedback. We will gently guide you on language where you might choose other words, and we hope that you will do the same for us. This is a learning opportunity for us all to practice inclusivity, and we thank you for your dedication to making this an inclusive space.

Autism

Autism, sometimes referred to as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and/or Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), is a developmental condition that usually emerges in the first three years and persists throughout the individual’s life. Though the key symptoms of autism fall into three general categories (see below), each person with autism exhibits symptoms in these domains in different ways and to varying degrees. This phenotypic heterogeneity reflects the high degree of variability in the genes underlying autism (Geschwind & Levitt, 2007). Though we have identified genetic differences associated with individual cases of autism, each accounts for only a small number of the actual cases, suggesting that no single genetic cause will apply in the majority of people with autism. There is currently no biological test for autism.

Autism is in the category of neurodevelopmental disorders, which includes Intellectual Disabilities, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and Learning Disorders, among others. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is defined by the presence of profound difficulties in social interactions and communication combined with the presence of repetitive or restricted interests, cognitions and behaviors. The diagnostic process involves a combination of parental report and clinical observation. Children with significant impairments across the social/communication domain who also exhibit repetitive behaviors can qualify for a diagnosis of autism. There is wide variability in the precise symptom profile an individual may exhibit.

Since Kanner first described autism in 1943, important commonalities in symptom presentation have been used to compile criteria for the diagnosis of autism. These diagnostic criteria have evolved during the past 70 years and continue to evolve (e.g., see the recent changes to the diagnostic criteria on the American Psychiatric Association’s website, http://www.dsm5.org/), yet impaired social functioning remains a required symptom for an autism diagnosis. Difficulties in social functioning are present in varying degrees for simple behaviors such as eye contact, and complex behaviors like navigating the give and take of a group conversation for individuals of all functioning levels (i.e. high or low IQ). Moreover, difficulties with social information processing occur in both visual (e.g., Pelphrey et al., 2002) and auditory (e.g., Dawson, Meltzoff, Osterling, Rinaldi, & Brown, 1998) sensory modalities.

Consider the results of an eye tracking study in which Pelphrey and colleagues (2002) observed that Autistic individuals did not make use of the eyes when judging facial expressions of emotion (see right panels of Figure 1). While repetitive behaviors or language difficulties are seen in other disorders (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder and specific language impairment, respectively), the basic social difficulties of this nature are unique to autism. Onset of the social deficits appears to precede difficulties in other domains (Osterling, Dawson, & Munson, 2002) and may emerge as early as 6 months of age (Maestro et al., 2002).

Defining the Social Brain

Within the past few decades, research has elucidated specific brain circuits that support perception of humans and other species. This social perception refers to “the initial stages in the processing of information that culminates in the accurate analysis of the dispositions and intentions of other individuals” (Allison, Puce, & McCarthy, 2000). Basic social perception is a critical building block for more sophisticated social behaviors, such as thinking about the motives and emotions of others. Brothers (1990) first suggested the notion of a social brain, a set of interconnected neuroanatomical structures that process social information, enabling the recognition of other individuals and the evaluation their mental states (e.g., intentions, dispositions, desires, and beliefs).

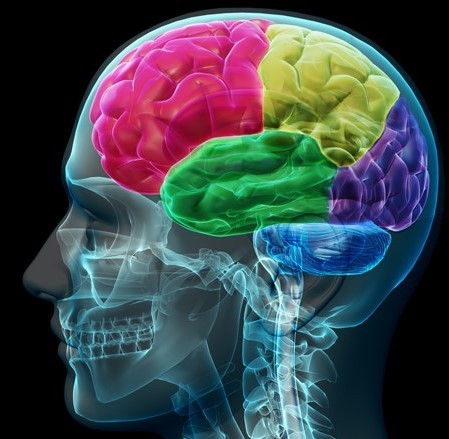

The social brain is hypothesized to consist of the amygdala, the orbital frontal cortex (OFC), fusiform gyrus (FG), and the posterior superior temporal sulcus (STS) region, among other structures. Though all areas work in coordination to support social processing, each appears to serve a distinct role. The amygdala helps us recognize the emotional states of others (e.g., Morris et al., 1996) and also to experience and regulate our own emotions (e.g., LeDoux, 1992). The OFC supports the “reward” feelings we have when we are around other people (e.g., Rolls, 2000). The FG, located at the bottom of the surface of the temporal lobes detects faces and supports face recognition (e.g., Puce, Allison, Asgari, Gore, & McCarthy, 1996). The posterior STS region recognizes the biological motion, including eye, hand and other body movements, and helps to interpret and predict the actions and intentions of others (e.g., Pelphrey, Morris, Michelich, Allison, & McCarthy, 2005).

Current Understanding of Social Perception in Autism

The social brain is of great research interest because the social difficulties characteristic of autism are thought to relate closely to the functioning of this brain network. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and event-related potentials (ERP) are complementary brain imaging methods used to study activity in the brain across the lifespan. Each method measures a distinct facet of brain activity and contributes unique information to our understanding of brain function.

FMRI uses powerful magnets to measure the levels of oxygen within the brain, which vary according to changes in neural activity. As the neurons in specific brain regions “work harder”, they require more oxygen. FMRI detects the brain regions that exhibit a relative increase in blood flow (and oxygen levels) while people listen to or view social stimuli in the MRI scanner. The areas of the brain most crucial for different social processes are thus identified, with spatial information being accurate to the millimeter.

In contrast, ERP provides direct measurements of the firing of groups of neurons in the cortex. Non-invasive sensors on the scalp record the small electrical currents created by this neuronal activity while the subject views stimuli or listens to specific kinds of information. While fMRI provides information about where brain activity occurs, ERP specifies when by detailing the timing of processing at the millisecond pace at which it unfolds.

ERP and fMRI are complementary, with fMRI providing excellent spatial resolution and ERP offering outstanding temporal resolution. Together, this information is critical to understanding the nature of social perception in autism. To date, the most thoroughly investigated areas of the social brain in autism are the superior temporal sulcus (STS), which underlies the perception and interpretation of biological motion, and the fusiform gyrus (FG), which supports face perception. Heightened sensitivity to biological motion (for humans, motion such as walking) serves an essential role in the development of humans and other highly social species. Emerging in the first days of life, the ability to detect biological motion helps to orient vulnerable young to critical sources of sustenance, support, and learning, and develops independent of visual experience with biological motion (e.g., Simion, Regolin, & Bulf, 2008). This inborn “life detector” serves as a foundation for the subsequent development of more complex social behaviors (Johnson, 2006).

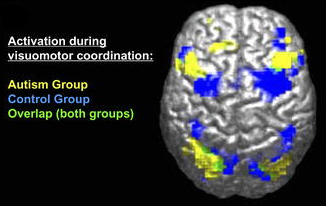

From very early in life, children with autism display reduced sensitivity to biological motion (Klin, Lin, Gorrindo, Ramsay, & Jones, 2009). Individuals with autism have reduced activity in the STS during biological motion perception. Similarly, people at increased genetic risk for autism but who do not develop symptoms of the disorder (i.e., unaffected siblings of individuals with autism) show increased activity in this region, which is hypothesized to be a compensatory mechanism to offset genetic vulnerability (Kaiser et al., 2010).

In neurotypical development, preferential attention to faces and the ability to recognize individual faces emerge in the first days of life (e.g., Goren, Sarty, & Wu, 1975). The special way in which the brain responds to faces usually emerges by three months of age (e.g., de Haan, Johnson, & Halit, 2003) and continues throughout the lifespan (e.g., Bentin et al., 1996). Autistic children, however, tend to show decreased attention to human faces by six to 12 months (Osterling & Dawson, 1994). Autistic children also show reduced activity in the FG when viewing faces (e.g., Schultz et al., 2000). Slowed processing of faces (McPartland, Dawson, Webb, Panagiotides, & Carver, 2004) is a characteristic of Autistic people that is shared by parents of children with autism (Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005) and infants at increased risk for developing autism because of having a sibling with autism(McCleery, Akshoomoff, Dobkins, & Carver, 2009). Behavioral and attentional differences in face perception and recognition are evident in Autistic children and adults as well (e.g., Hobson, 1986).

Exploring Diversity in Autism

Because of the limited quality of the behavioral methods used to diagnose autism and current clinical diagnostic practice, which permits similar diagnoses despite distinct symptom profiles (McPartland, Webb, Keehn, & Dawson, 2011), it is possible that the group of children currently referred to as having autism may actually represent different syndromes with distinct causes. Examination of the social brain may well reveal diagnostically meaningful subgroups of Autistic children. Measurements of the “where” and “when” of brain activity during social processing tasks provide reliable sources of the detailed information needed to profile Autistic children with greater accuracy. These profiles, in turn, may help to inform the development of supports by helping us to match specific supports to specific profiles.

The integration of imaging methods is critical for this endeavor. Using face perception as an example, the combination of fMRI and ERP could identify who, of those Autistic individuals, shows anomalies in the FG and then determine the stage of information processing at which these anomalies occur. Because different processing stages often reflect discrete cognitive processes, this level of understanding could encourage supports that address specific processing differences at the neural level.

For example, differences observed in the early processing stages might reflect problems with low-level visual perception, while later differences would indicate problems with higher-order processes, such as emotion recognition. These same principles can be applied to the broader network of social brain regions and, combined with measures of behavioral functioning, could offer a comprehensive profile of brain-behavior performance for a given individual. A fundamental goal for this kind of subgroup approach is to improve the ability to tailor supports to the individual.

Another objective is to improve the power of other scientific tools. Most studies of Autistic individuals compare groups of individuals, for example, Autistic individuals compared to neurotypically developing peers. However, studies have also attempted to compare children by behavioral or cognitive characteristics (e.g., cognitively able versus developmentally delayed or anxious versus non-anxious). Yet, the power of a scientific study to detect these kinds of significant, meaningful, individual differences is only as strong as the accuracy of the factor used to define the compared groups.

The identification of distinct subgroups within autism according to information about the brain would allow for a more accurate and detailed exposition of the individual differences seen in Autistic people. This is especially critical for the success of investigations into the genetic basis of autism. As mentioned before, the genes discovered thus far account for only a small portion of autism cases. If meaningful, quantitative distinctions in Autistic individuals are identified; a more focused examination into the genetic causes specific to each subgroup could then be pursued. Moreover, distinct findings from neuroimaging, or biomarkers, can help guide genetic research. Endophenotypes, or characteristics that are not immediately available to observation but that reflect an underlying genetic potential, expose the most basic components of a complex psychiatric condition and are more stable across the lifespan than observable behavior (Gottesman & Shields, 1973). By describing the key characteristics of autism in these objective ways, neuroimaging research will facilitate identification of genetic contributions to autism.

Brain Development and Behaviour

Because autism is a developmental condition, it is particularly important to detect and understand the effects of autism early in life. Early differences in attention to biological motion, for instance, can hinder subsequent experiences in attending to higher level social information, thereby driving development toward more severe difficulties and stimulating struggles in additional domains of functioning, such as language development. Without early predictors of function, and in the absence of a firm diagnosis until behavioral symptoms emerge, supports are often delayed for two or more years, eclipsing a crucial period in which intervention may be particularly successful in ameliorating some of the social and communicative difficulties seen in autism.

In response to the great need for sensitive (able to identify subtle cases) and specific (able to distinguish autism from other disorders) early indicators of autism, such as biomarkers, many research groups from around the world have been studying patterns of infant development using prospective longitudinal studies of infant siblings of Autistic children and a comparison group of infant siblings without familial risks. Such designs gather longitudinal information about developmental trajectories across the first three years of life for both groups followed by clinical diagnosis at approximately 36 months.

These studies are problematic in that many of the social features of autism do not emerge in development until after 12 months of age, and it is not certain that these symptoms will manifest during the limited periods of observation involved in clinical evaluations or in pediatricians’ offices. Moreover, across development, but especially during infancy, behavior is widely variable and often unreliable, and at present, behavioral observation is the only means to detect symptoms of autism and to confirm a diagnosis. This is quite problematic because, even highly sophisticated behavioral methods, such as eye tracking (see Figure 1), do not necessarily reveal reliable differences in Autistic infants (Ozonoff et al., 2010). However, measuring the brain activity associated with social perception can detect differences that do not appear in behavior until much later. The identification of biomarkers utilizing the imaging methods we have described offers promise for earlier detection of atypical social development.

ERP measures of brain response predict subsequent development of autism in infants as young as six months old who showed neurotypical patterns of visual fixation (as measured by eye tracking) (Elsabbagh et al., 2012). This suggests the great promise of brain imaging for earlier recognition of autism.

Hope for Improved Outcomes

The brain imaging research described above offers hope for the future of supports for autism. Many of the functions of the social brain demonstrate significant plasticity, meaning that their functioning can be affected by experience over time. In contrast to theories that suggest difficulty processing complex information or communicating across large expanses of cortex (Minshew & Williams, 2007), this malleability of the social brain is a positive prognosticator for the development of supports. Given the observed plasticity of the social brain, supporting those experiencing difficulties may be possible with appropriate and timely intervention.

The social environment in which a person lives, especially social support from parents, friends, and instructors, can have a positive impact on the lives of Autistic people. For example, the social environment of a job can positively impact their social development (Taylor et al, 2014). Similarly, research often reveals that it is not the symptoms of autism itself that interferes with a person’s wellbeing, but the bullying, stigma, and concealment of symptoms that sometimes accompanies autism (Hong et al, 2016). Taken together, these lines of research suggest that supportive social environments are crucial for the wellbeing of those with autism.

It should be noted that many Autistic individuals have expressed concern that approaches focused on “treatment” for autism is trying to erase Autistic children’s unique personalities and strengths. Some advocate for the idea that Autistic people do not need “treatment,” rather it is the world that needs to change to accommodate Autistic people. Indeed, every effort should be made to build inclusive environments, and eliminate stigma about autism. Additionally, supporting individuals at a young age is important for the development of skills such as language and some social understanding.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- Endophenotypes

- A characteristic that reflects a genetic liability for disease and a more basic component of a complex clinical presentation. Endophenotypes are less developmentally malleable than overt behavior.

- Measures the firing of groups of neurons in the cortex. As a person views or listens to specific types of information, neuronal activity creates small electrical currents that can be recorded from non-invasive sensors placed on the scalp. ERP provides excellent information about the timing of processing, clarifying brain activity at the millisecond pace at which it unfolds.

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

- Entails the use of powerful magnets to measure the levels of oxygen within the brain that vary with changes in neural activity. That is, as the neurons in specific brain regions “work harder” when performing a specific task, they require more oxygen. By having people listen to or view social percepts in an MRI scanner, fMRI specifies the brain regions that evidence a relative increase in blood flow. In this way, fMRI provides excellent spatial information, pinpointing with millimeter accuracy, the brain regions most critical for different social processes.

- The set of neuroanatomical structures that allows us to understand the actions and intentions of other people.

References

- Allison, T., Puce, A., & McCarthy, G. (2000). Social perception from visual cues: Role of the STS region. Trends in Cognitive Science, 4(7), 267–278.

- Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E., et al. (1996). Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8(6), 551–565.

- Brothers, L. (1990). The social brain: A project for integrating primate behavior and neurophysiology in a new domain. Concepts in Neuroscience, 1, 27–51.

- Dawson, G., Meltzoff, A. N., Osterling, J., Rinaldi, J., & Brown, E. (1998). Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 28(6), 479–485.

- Dawson, G., Webb, S. J., & McPartland, J. (2005). Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: Insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Developmental Neuropsychology, 27(3), 403–424.

- Elsabbagh, M., Mercure, E., Hudry, K., Chandler, S., Pasco, G., Charman, T., et al. (2012). Infant neural sensitivity to dynamic eye gaze is associated with later emerging autism. Current Biology, 22(4), 338–342.

- Geschwind, D. H., & Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: Developmental disconnection syndromes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17(1), 103–111.

- Goren, C. C., Sarty, M., & Wu, P. Y. (1975). Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants. Pediatrics, 56(4), 544–549.

- Gottesman I. I., & Shields, J. (1973) Genetic theorizing and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 122, 15–30.

- Hobson, R. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(3), 321–342.

- Johnson, M. H. (2006). Biological motion: A perceptual life detector? Current Biology, 16(10), R376–377.

- Kaiser, M. D., Hudac, C. M., Shultz, S., Lee, S. M., Cheung, C., Berken, A. M., et al. (2010). Neural signatures of autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(49), 21223–21228.

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250.

- Klin, A., Lin, D. J., Gorrindo, P., Ramsay, G., & Jones, W. (2009). Two-year-olds with autism orient to non-social contingencies rather than biological motion. Nature, 459(7244), 257–261.

- LeDoux, J. E. (1992). Brain mechanisms of emotion and emotional learning. Current opinion in neurobiology, 2(2), 191-197.

- Maestro, S., Muratori, F., Cavallaro, M. C., Pei, F., Stern, D., Golse, B., et al. (2002). Attentional skills during the first 6 months of age in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(10), 1239–1245.

- McCleery, J. P., Akshoomoff, N., Dobkins, K. R., & Carver, L. J. (2009). Atypical face versus object processing and hemispheric asymmetries in 10-month-old infants at risk for autism. Biological Psychiatry, 66(10), 950–957.

- McPartland, J. C., Dawson, G., Webb, S. J., Panagiotides, H., & Carver, L. J. (2004). Event-related brain potentials reveal anomalies in temporal processing of faces in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1235–1245.

- McPartland, J. C., Webb, S. J., Keehn, B., & Dawson, G. (2011). Patterns of visual attention to faces and objects in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Develop Disorders, 41(2), 148–157.

- Minshew, N. J., & Williams, D. L. (2007). The new neurobiology of autism: Cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Archives of Neurology, 64(7), 945–950.

- Morris, J. S., Friston, K. J., Büchel, C., Frith, C. D., Young, A. W., Calder, A. J., & Dolan, R. J. (1998). A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain: a journal of neurology, 121(1), 47-57.

- Osterling, J., & Dawson, G. (1994). Early recognition of children with autism: A study of first birthday home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 247-257.

- Osterling, J. A., Dawson, G., & Munson, J. A. (2002). Early recognition of 1-year-old infants with autism spectrum disorder versus mental retardation. Development & Psychopathology, 14(2), 239–251.

- Ozonoff, S., Iosif, A. M., Baguio, F., Cook, I. C., Hill, M. M., Hutman, T., et al. (2010). A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(3), 256–266.

- Pelphrey, K. A., Morris, J. P., Michelich, C. R., Allison, T., & McCarthy, G. (2005). Functional anatomy of biological motion perception in posterior temporal cortex: an fMRI study of eye, mouth and hand movements. Cerebral cortex, 15(12), 1866-1876.

- Pelphrey, K. A., Sasson, N. J., Reznick, J. S., Paul, G., Goldman, B. D., & Piven, J. (2002). Visual scanning of faces in autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 249–261.

- Puce, A., Allison, T., Asgari, M., Gore, J. C., & McCarthy, G. (1996). Differential sensitivity of human visual cortex to faces, letterstrings, and textures: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of neuroscience, 16(16), 5205-5215.

- Rolls, E. T. (2000). The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cerebral cortex, 10(3), 284-294.

- Schultz, R. T., Gauthier, I., Klin, A., Fulbright, R. K., Anderson, A. W., Volkmar, F., et al. (2000). Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(4), 331–340.

- Simion, F., Regolin, L., & Bulf, H. (2008). A predisposition for biological motion in the newborn baby. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(2), 809–813.

- de Haan, M., Johnson, M. H., & Halit, H. (2003). Development of face-sensitive event-related potentials during infancy: A review. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 51(1), 45–58.

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Pelphrey, K. A. (2019). Autism: insights from the study of the social brain. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/yqdepwgt

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/yqdepwgt.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.

Geschwind, D. H., & Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: Developmental disconnection syndromes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17(1), 103–111.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217–250.

Pelphrey, K. A., Sasson, N. J., Reznick, J. S., Paul, G., Goldman, B. D., & Piven, J. (2002). Visual scanning of faces in autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 249–261.

Dawson, G., Meltzoff, A. N., Osterling, J., Rinaldi, J., & Brown, E. (1998). Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 28(6), 479–485.

Osterling, J. A., Dawson, G., & Munson, J. A. (2002). Early recognition of 1-year-old infants with autism spectrum disorder versus mental retardation. Development & Psychopathology, 14(2), 239–251.

Maestro, S., Muratori, F., Cavallaro, M. C., Pei, F., Stern, D., Golse, B., et al. (2002). Attentional skills during the first 6 months of age in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(10), 1239–1245.

Allison, T., Puce, A., & McCarthy, G. (2000). Social perception from visual cues: Role of the STS region. Trends in Cognitive Science, 4(7), 267–278.

Brothers, L. (1990). The social brain: A project for integrating primate behavior and neurophysiology in a new domain. Concepts in Neuroscience, 1, 27–51.

The set of neuroanatomical structures that allows us to understand the actions and intentions of other people.

Morris, J. S., Friston, K. J., Büchel, C., Frith, C. D., Young, A. W., Calder, A. J., & Dolan, R. J. (1998). A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain: a journal of neurology, 121(1), 47-57.

LeDoux, J. E. (1992). Brain mechanisms of emotion and emotional learning. Current opinion in neurobiology, 2(2), 191-197.

Rolls, E. T. (2000). The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cerebral Cortex, 10(3), 284-294.

Puce, A., Allison, T., Asgari, M., Gore, J. C., & McCarthy, G. (1996). Differential sensitivity of human visual cortex to faces, letterstrings, and textures: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of neuroscience, 16(16), 5205-5215.

Pelphrey, K. A., Morris, J. P., Michelich, C. R., Allison, T., & McCarthy, G. (2005). Functional anatomy of biological motion perception in posterior temporal cortex: an fMRI study of eye, mouth and hand movements. Cerebral cortex, 15(12), 1866-1876.

Entails the use of powerful magnets to measure the levels of oxygen within the brain that vary with changes in neural activity. That is, as the neurons in specific brain regions “work harder” when performing a specific task, they require more oxygen. By having people listen to or view social percepts in an MRI scanner, fMRI specifies the brain regions that evidence a relative increase in blood flow. In this way, fMRI provides excellent spatial information, pinpointing with millimeter accuracy, the brain regions most critical for different social processes.

Measures the firing of groups of neurons in the cortex. As a person views or listens to specific types of information, neuronal activity creates small electrical currents that can be recorded from non-invasive sensors placed on the scalp. ERP provides excellent information about the timing of processing, clarifying brain activity at the millisecond pace at which it unfolds.

Simion, F., Regolin, L., & Bulf, H. (2008). A predisposition for biological motion in the newborn baby. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(2), 809–813.

Johnson, M. H. (2006). Biological motion: A perceptual life detector? Current Biology, 16(10), R376–377.

Klin, A., Lin, D. J., Gorrindo, P., Ramsay, G., & Jones, W. (2009). Two-year-olds with autism orient to non-social contingencies rather than biological motion. Nature, 459(7244), 257–261.

Kaiser, M. D., Hudac, C. M., Shultz, S., Lee, S. M., Cheung, C., Berken, A. M., et al. (2010). Neural signatures of autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(49), 21223–21228.

Goren, C. C., Sarty, M., & Wu, P. Y. (1975). Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants. Pediatrics, 56(4), 544–549.

de Haan, M., Johnson, M. H., & Halit, H. (2003). Development of face-sensitive event-related potentials during infancy: A review. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 51(1), 45–58.

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E., et al. (1996). Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8(6), 551–565.

Osterling, J., & Dawson, G. (1994). Early recognition of children with autism: A study of first birthday home videotapes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 247-257.

Schultz, R. T., Gauthier, I., Klin, A., Fulbright, R. K., Anderson, A. W., Volkmar, F., et al. (2000). Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(4), 331–340.

McPartland, J. C., Dawson, G., Webb, S. J., Panagiotides, H., & Carver, L. J. (2004). Event-related brain potentials reveal anomalies in temporal processing of faces in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1235–1245.

Dawson, G., Webb, S. J., & McPartland, J. (2005). Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: Insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Developmental Neuropsychology, 27(3), 403–424.

McCleery, J. P., Akshoomoff, N., Dobkins, K. R., & Carver, L. J. (2009). Atypical face versus object processing and hemispheric asymmetries in 10-month-old infants at risk for autism. Biological Psychiatry, 66(10), 950–957.

Hobson, R. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(3), 321–342.

McPartland, J. C., Webb, S. J., Keehn, B., & Dawson, G. (2011). Patterns of visual attention to faces and objects in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Develop Disorders, 41(2), 148–157.

A characteristic that reflects a genetic liability for disease and a more basic component of a complex clinical presentation. Endophenotypes are less developmentally malleable than overt behavior.

Gottesman I. I., & Shields, J. (1973) Genetic theorizing and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 122, 15–30.

Ozonoff, S., Iosif, A. M., Baguio, F., Cook, I. C., Hill, M. M., Hutman, T., et al. (2010). A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(3), 256–266.

Elsabbagh, M., Mercure, E., Hudry, K., Chandler, S., Pasco, G., Charman, T., et al. (2012). Infant neural sensitivity to dynamic eye gaze is associated with later emerging autism. Current Biology, 22(4), 338–342.

Minshew, N. J., & Williams, D. L. (2007). The new neurobiology of autism: Cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Archives of Neurology, 64(7), 945–950.