6 What to do when things go wrong

In this chapter

- Disruptions during a videoconference

- Issues with a difficult student

- When a student is in distress

- The case of a grade dispute

- If you suspect academic dishonesty

- Issues with other TAs or the course supervisor

Disruptions during a videoconference

Things can go wrong online just like they can in the physical classroom. By staying calm and being prepared, you can prevent and address these issues.

First and foremost: you always have the option of stopping or leaving the session. If you are not sure what to do about an issue, stop the session and follow up with students as soon as possible. Now let’s address how to prevent issues by (1) knowing the technology, (2) being clear about expectations from the start, (3) building a respectful community, and (4) addressing issues that arise.

1. Know the technology

Practice using the videoconference software before the first DGD/tutorial. In particular, learn how to control the following options: mute/unmute microphones, turn on/off videos, turn on/off participants’ screensharing and screen annotation abilities, remove participant, and chat.

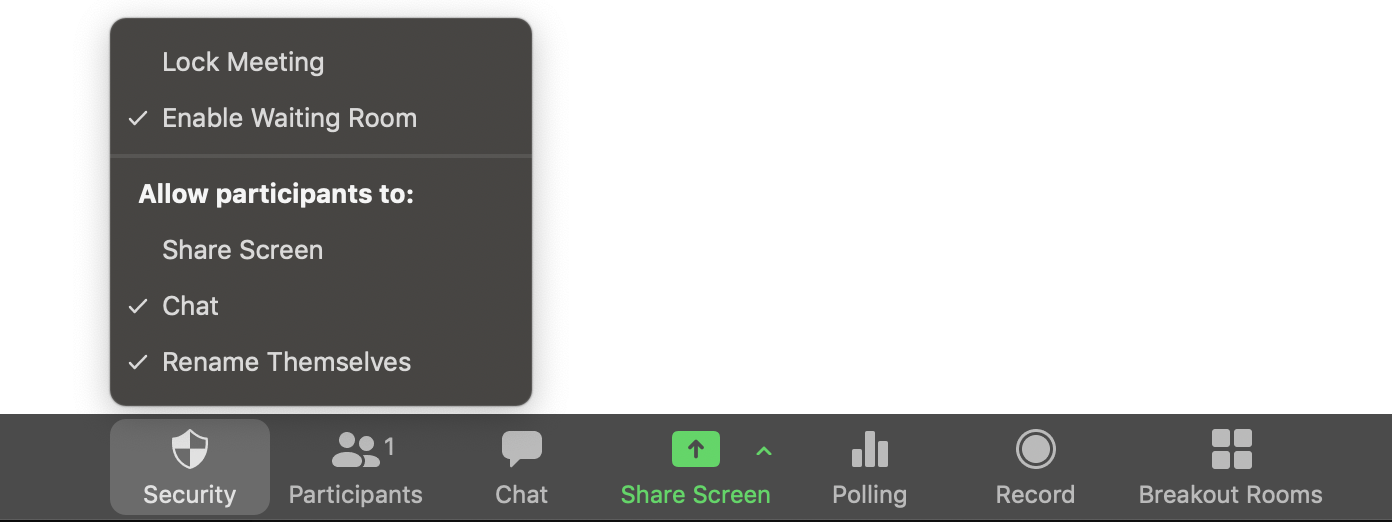

For example in Zoom, you can:

- Create the connection link using a password, currently a default setting in Zoom that should be used

- For institutions or accounts with Single Sign-On (SSO), you can require sign-in only from authenticated accounts (e.g., at uOttawa)

- Enable the “waiting room” once most students have joined

- Disable screen sharing, or enable it only for specific purposes

- Chat can be disabled if needed, although this limits community-building and students’ ability to ask questions (of you or each other)

- Lock the meeting, but this will make it challenging for students to join/re-join if they have connection issues (or scheduling issues)

- Remove participants by clicking on participants then selecting the one(s) to be removed (should be done only if essential)

2. Be clear about expectations from the start

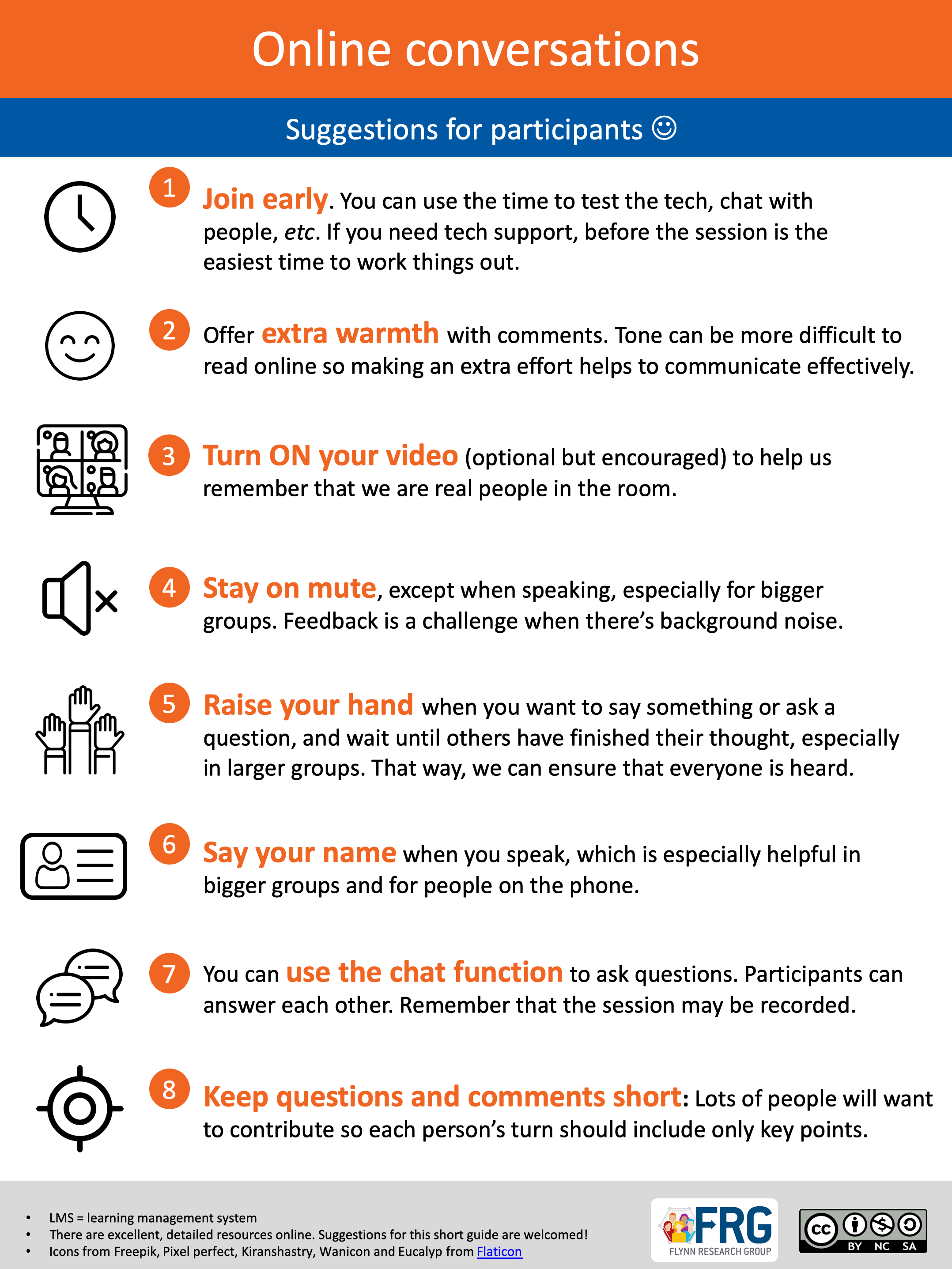

During videoconferencing, share expectations for online communication. For example, you could use or adapt the guide below; the file can be found in the “Quick start overview and resource documents“. PDF here.

Online conversation skills, PDF version.

3. Build a respectful community

Major goals in an online course are to build community and trust, engage students in the course, and help them take greater ownership of their learning process. When students and the instructor/TA trust each other, the whole environment becomes more positive and respectful. To that end, we have a few recommendations:

- Students are generally excellent at online etiquette, so they can be trusted to stay on mute if necessary when others are speaking or in large groups and to use the chat function responsibly. Don’t close the chat as doing so shuts off a main way that students can communicate with each other, ask questions, and build community.

- Encourage students to use their video and encourage oral participation (i.e., unmute to speak), but make this optional. While sharing our video lets us remember that we are working with real people online, students (or TAs and instructors!) may not want their home environment shared, for a number of reasons.

- Similarly, encourage students to upload a profile photo of themselves on Brightspace.

4. Address issues that arise

Remember: you always have the option of stopping or leaving the session. If you are not sure what to do about an issue, stop the session and follow up with students as soon as possible.

Behaviour issues

- Serious issues like uninvited participants making rude, racist, sexist, etc. comments:

- Remove the “participant” and either lock the videoconference or enable the waiting room so that you control any other entrances

- Participants getting off-topic, spamming the chat with emoticons, etc.:

- Ask participants to keep the messages focused on the conversation at hand

- Student being disruptive, lacking professionalism:

- Gently ask them to return to the topic at hand or to stop the action (scribbling on whiteboard, talking over someone else); assume the best: that they don’t realize the effects of their behaviour

- Send an individual chat message or email

- If the behaviour is really inappropriate (e.g., racist comment): tell the person to stop immediately and publicly; this not only stops the behaviour but shows all participants that you will protect them and the learning space

- Remind the student that everyone is there to learn, has paid for the course, committed time and energy, and given up other activities to be here

- If needed, mute their microphone (sometimes people leave it on by accident and start talking to their cat)

- You could also send out a general reminder to everyone about the importance of mutual respect in the course

Connection and technology issues

- Always record synchronous sessions for equity reasons

- Test the equipment beforehand

- If you tend to have bandwidth issues

- Send the slides/content to the students ahead of time

- Put screenshots or other documents into the chat

- Turn your video off if needed

- Give your sessions from a different location, if possible

- If your audio is bad

- Borrow a microphone from the university (if possible)

- Be mindful that students may have the same issues

- Offer options: video on/off

- Watch a video at a different time

- Use the chat instead of answering orally

- If a technology is not working as intended, use a different method or move on. Maybe the polling software is not working so you create a question on the whiteboard instead, or you ask students to discuss in breakout rooms.

Other issues

- Other issues may arise, like students not finding a button or needing time to load up a new activity/website.

- Anticipate that new activities and software will take a little longer the first time.

- Students may be confused at the instructions:

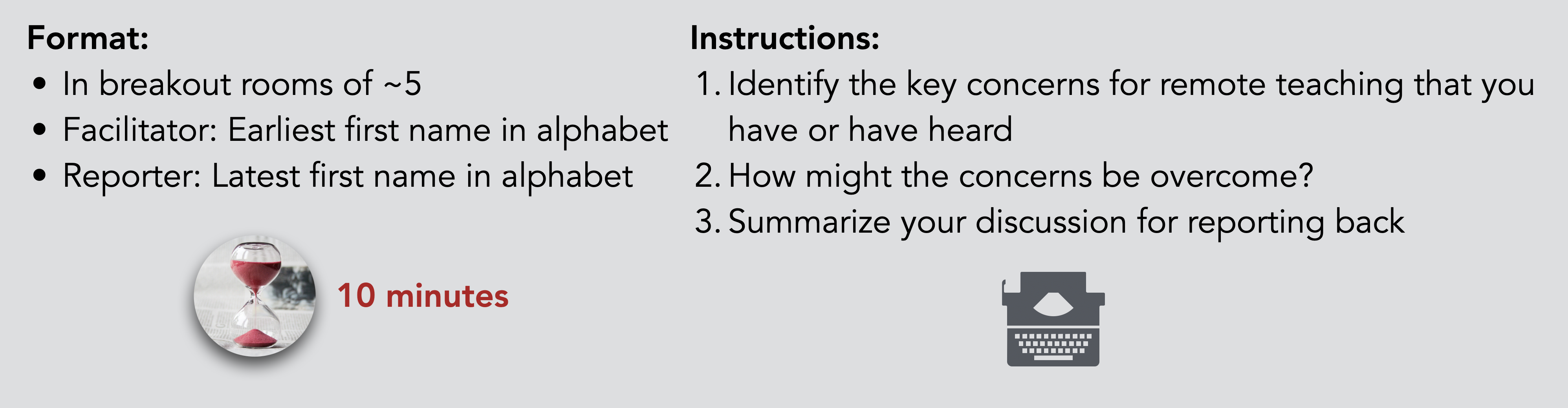

- Write down the instructions, keep them to 3 steps max, and include the amount of time allocated; an example is shown below. If the activity needs more than that, give the first few instructions so they can get started, then build in the rest. If you need to give more than 3 instructions at a time, consider simplifying the activity.

Issues with a difficult student

The following recommendations are adapted those from Stanford University’s Teaching Commons.

- “First, maintain a safe environment for your students, which means preventing the debate from turning into a prolonged attack on either individual students or groups with whom students may identify. It also means keeping your cool and staying respectful if a student challenges you; this preserves students’ trust in you.” – Classroom Challenges, Stanford University

- Decide whether a conversation is appropriate in the moment, whether to arrange another time to discuss, or whether to refer the student to the course supervisor.

During the conversation:

- Identify the source of the concern. To better understand the issue, listen carefully and ask questions. Take a deep breath and stay calm.

- Use evidence when disagreeing with a student and ask students to provide evidence for their positions. Don’t use your position as a reason to be right (e.g., I know this because I am a TA)

- Avoid “teasing or sarcastic humour, since these are all too often easily misinterpreted.” – Classroom Challenges, Stanford University

- You may want to brainstorm or outline the options

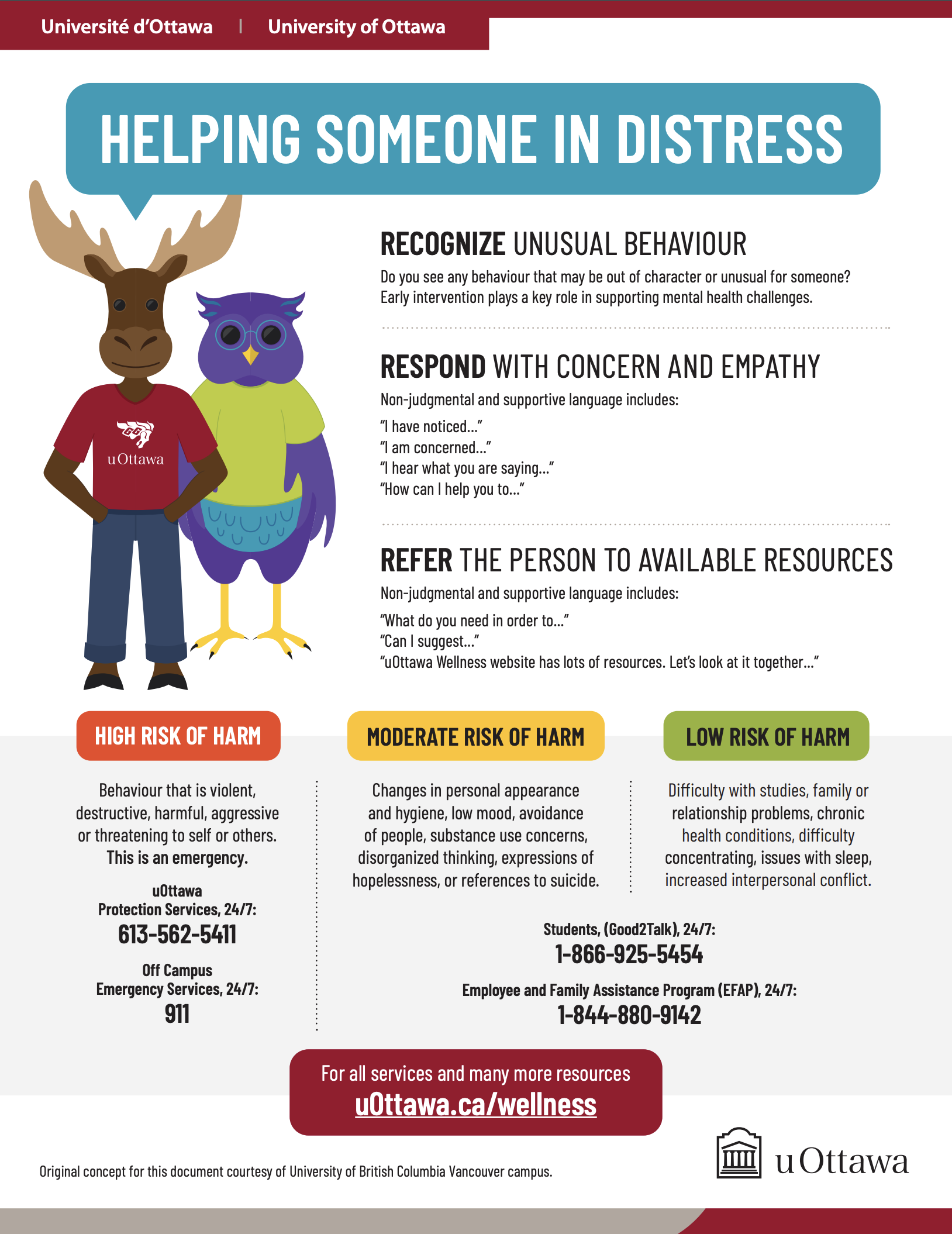

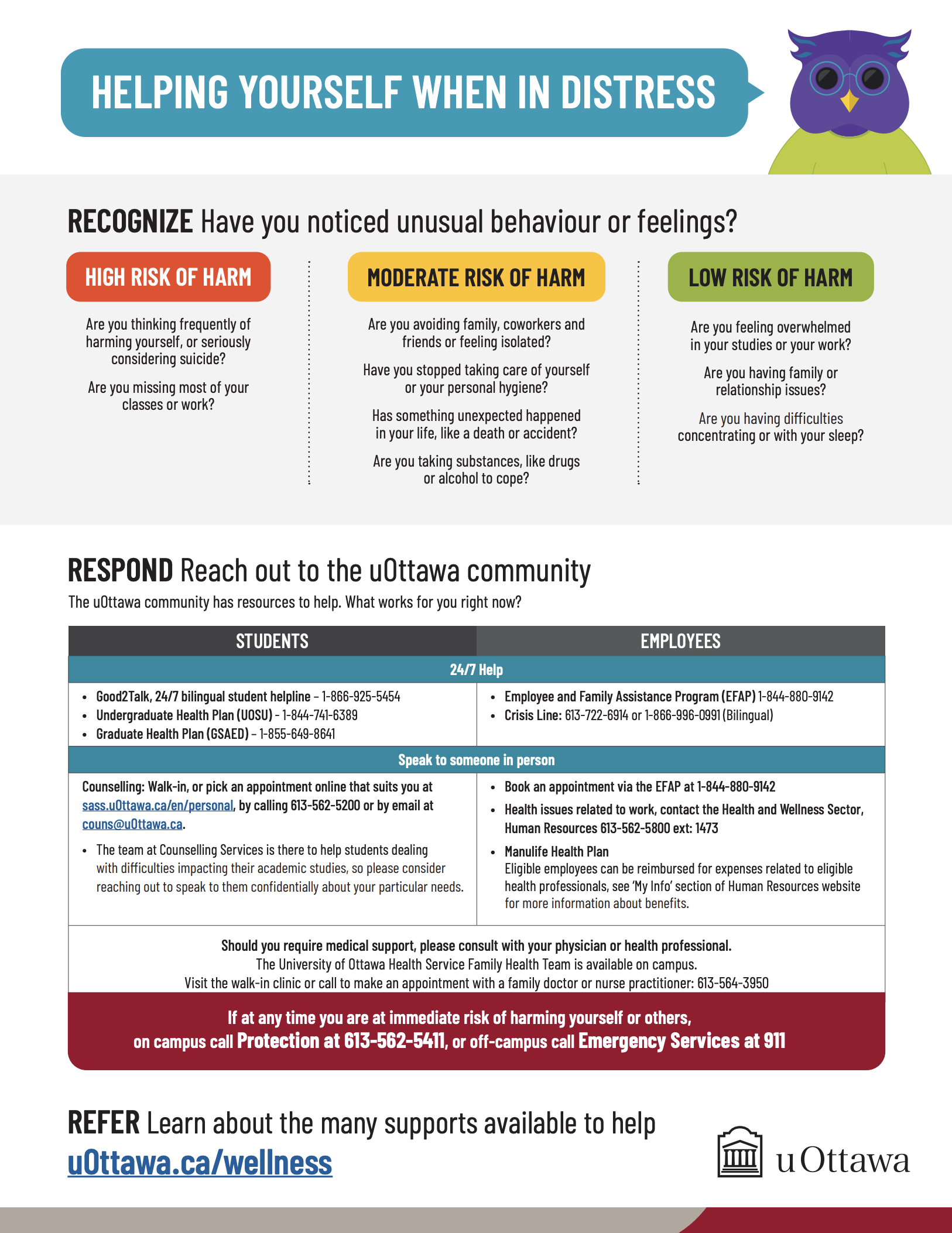

When a student is in distress

uOttawa has a series of recommendations to help a person in distress, including if you yourself are in distress. Their quick guide below gives some good starting points (PDF).

The case of a grade dispute

Discuss your responsibilities regarding grade disputes with the course supervisor (see communication chapter). If part of your responsibility includes discussing grades, the following suggestions may be helpful. They come from the University of Toronto’s Teaching Assistant Training Program, with some adaptations.

1. “I met all the criteria in the assignment. Why did I only get a ‘C’?”

Possible response: “Let’s take a look by comparing your answers with the marking scheme/rubric.” If you don’t know where the student lost marks, it’s okay to say that and suggest they follow up with the course professor.

2. “Most of your comments on my paper were about grammar, spelling, and writing skills. But this course is about ______. You should only be grading me on my knowledge of the subject content.”

If communication skills are part of the expectations in the course, explain this expectation to the student and refer them to the location where those expectations are communicated (likely the syllabus). If this expectation has not been communicated, you can ask the course professor to clarify the expectations.

3. “Your standards are too high.”

Possible response: “Let’s take a look by comparing your answers with the marking scheme/rubric.” If possible, share examples of past work, with permission and with identifying information removed.

4. “I’m an ‘A’ student, yet you only gave me a ‘C’ in this course/assessment!”

Possible response: “I understand you’re worried, and that this might be a different result from what you’ve received in the past. However, this mark assesses your performance on this work/course only.”

5. “I put a lot of effort into this paper, but you only gave me a ‘C’.”

Possible response: “I know you put a lot of work into this. Unfortunately, we were expecting more in the assignment. Do you want to look over the paper and see what happened?”

If you suspect academic dishonesty

If you suspect academic dishonesty, start by contacting the course supervisor. You can also learn more in uOttawa’s academic integrity webpage.

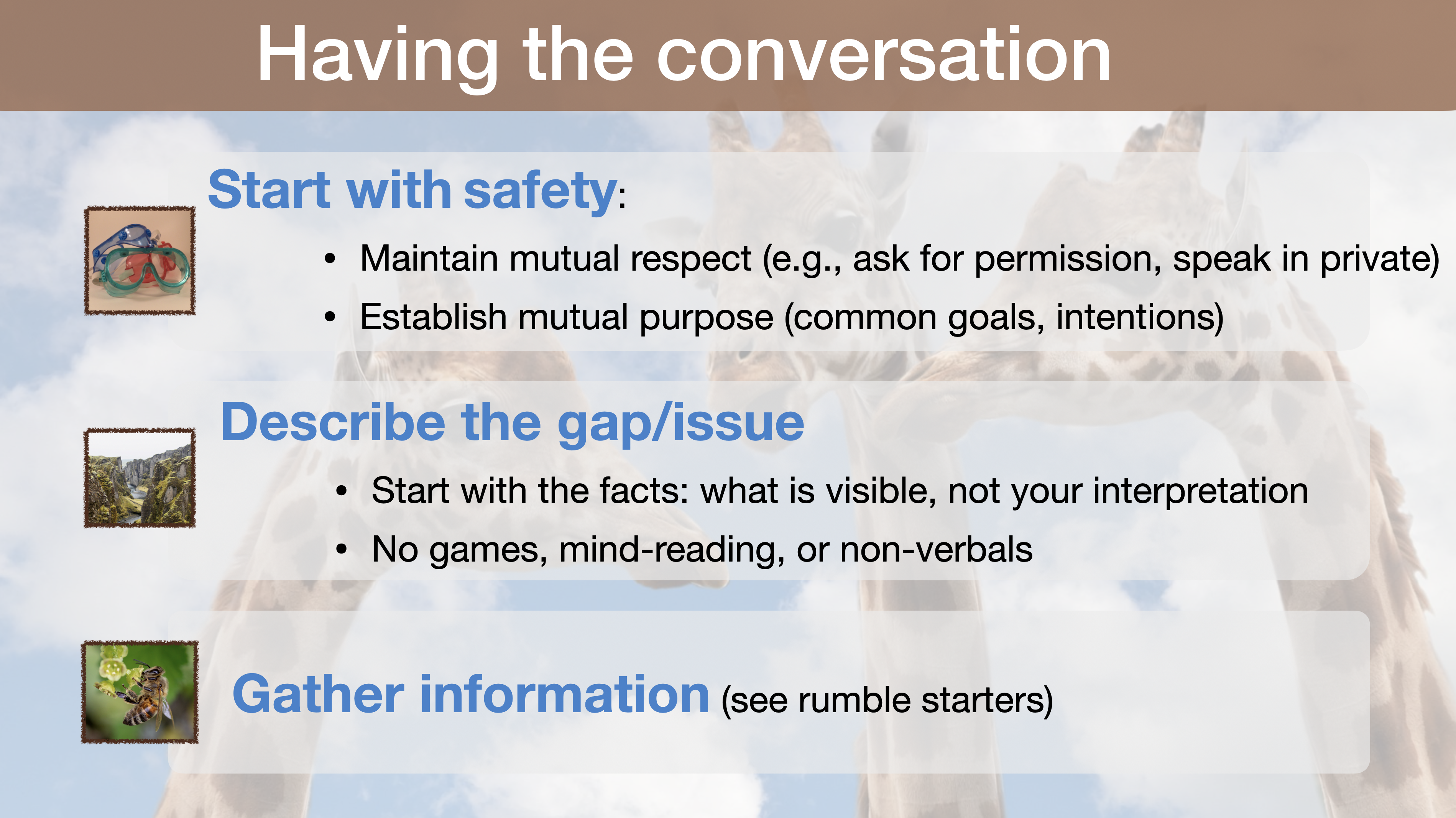

Issues with other TAs or the course supervisor

We recommend talking with the person as a starting point. We developed the recommendations in this section from two books (Dare to Lead and Crucial Conversations) and a workshop that we have run, called Navigating Tough Conversations (slides). As you get ready to have the conversation, remember that it’s okay to:

- Set a time in advance

- Write down your ideas, in advance and/or during the conversation

- Take breaks

When you’re ready to have the conversation, here are some suggestions (PDF):

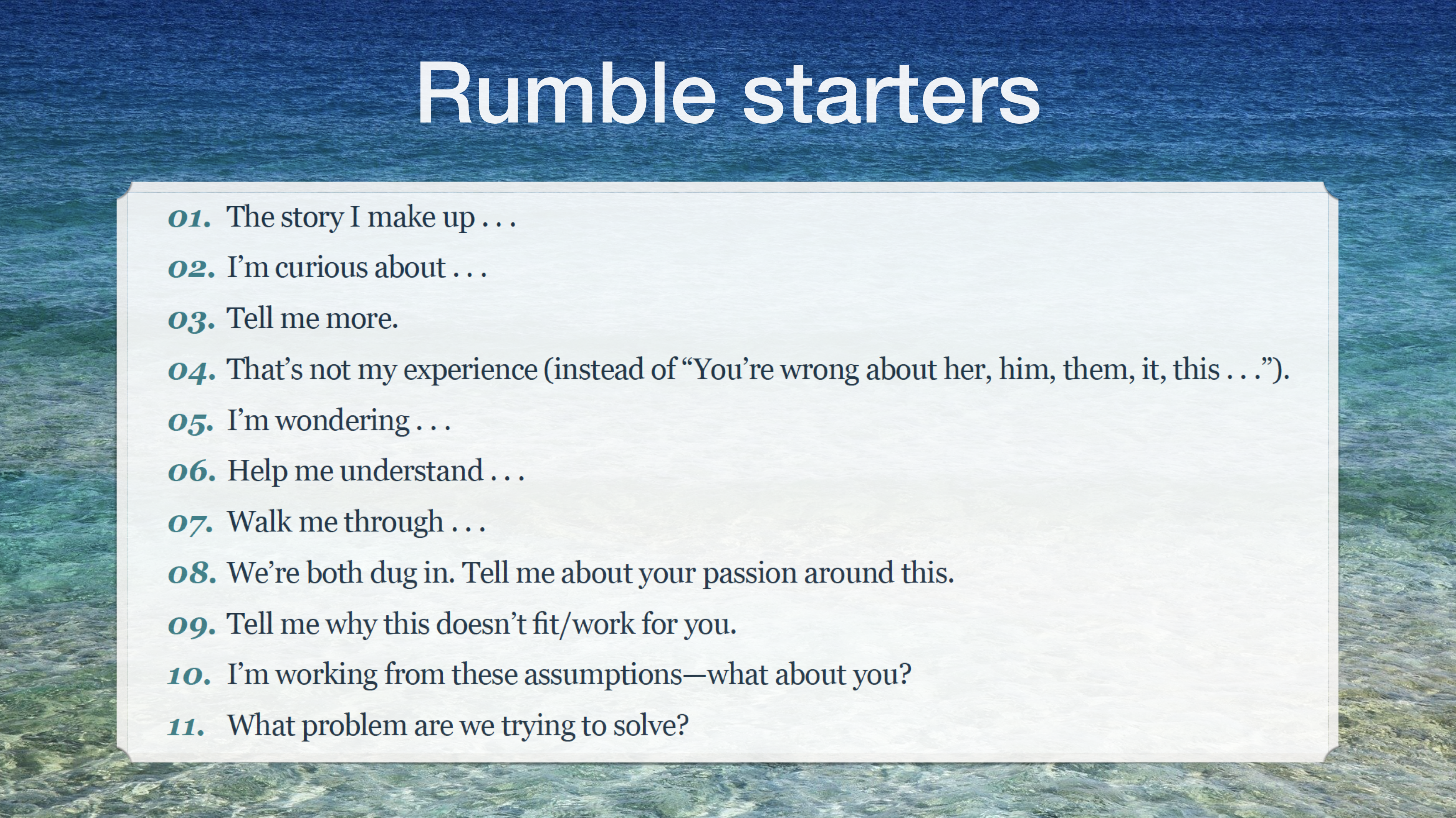

As you gather information, here are a few ways you can start out (PDF):

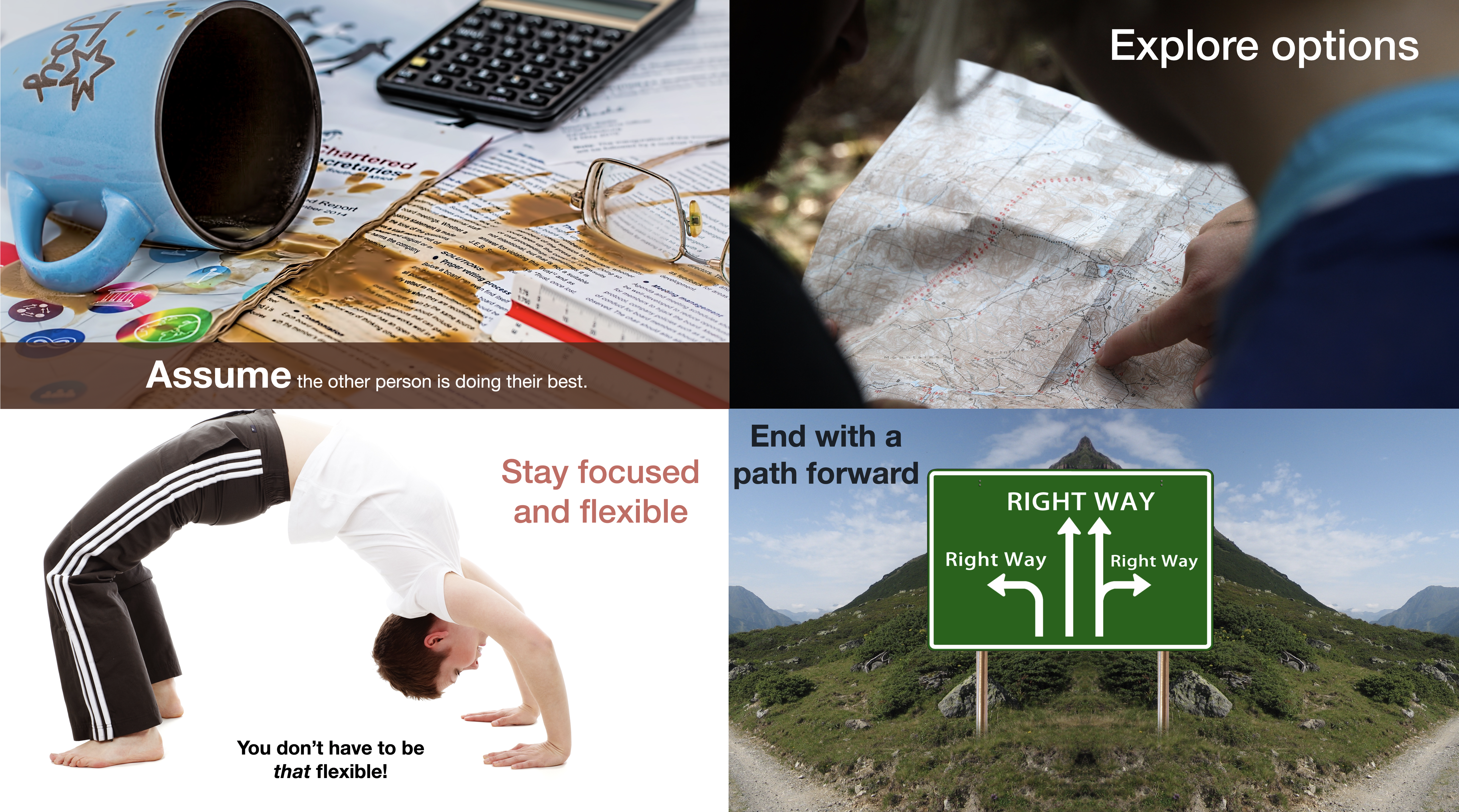

During the conversation, consider keeping a few things in mind (PDF):

Remember to end with a path forward. What are the next steps? Will you check back in on a certain date to see how things are going?

If you can’t get to a resolution, you may want to bring the issue forward. For example, an issue with another TA could be discussed with the course supervisor. An issue with the professor could be discussed with the Department Chair/Head.

To go deeper

- File sizes and types are an issue to contend with in the virtual/online environment. Where possible, suggest specific file types to use (e.g., PDF, png, mp4). Kyle Mackie has additional suggestions about working with file types online.

- You may receive emails or read other messages from students about their frustrations (e.g., about marks, exam formats, deadlines). Refer to the chapter on Communication for suggestions.

- Crucial conversations is a great book about tough conversations. Another great one is Dare to Lead.

Up next

The next chapter addresses creating videos.

Please feel free to contact us at any time with questions, suggestions, and concerns. In particular, we check this form weekly and will continue to update this guide as the situation evolves.

During synchronous instruction, the professor and students are online at the same time. Synchronous modes can include videoconferencing, brainstorming spaces (whiteboard, Miro), etc.

Bandwidth describes the maximum data transfer rate of a network or Internet connection. More info: https://techterms.com/definition/bandwidth