4.5: Standard Business Style

Learning Objectives

3. Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Among the most important skills in communication is to adjust your style according to the audience to meet their needs as well as your own. You would speak differently to a customer or manager compared with how you would to a long-time co-worker who has also become a friend. In each case, these audiences have certain expectations about your style of communication, and you must meet those expectations to be respected and maintain good relations. This section reviews those style choices and focuses especially on the six major characteristics of good writing common to both formal and casual writing.

4.5.1: The Formality Spectrum

We began looking at the general choice between a formal and informal style of writing based on how you’ve profiled your audience’s position in relation to you in §2.2.3. There, we saw how certain situations call for formal writing and others for a more relaxed style and saw in Table 2.2.3 that these styles involve word choices along a spectrum of synonyms from “slangy” to casual to fancy. Here we will review those considerations in the context of the writing process.

1. Formal Style in Writing

Because a formal style of writing shows respect for the reader, use standard business English, especially if your goal is to curry favour with your audience, such as anyone outside your organization, higher than you within your organization, and those on or around your level whom you have never communicated with before. These audiences include managers, customers, clients, B2B suppliers and vendors, regulators, and other interested stakeholders such as government agencies. A cover letter, for instance, will be read by a future potential manager probably unfamiliar to you, so it is a very real test of your ability to write formally—a test that is crucial to your career success. Many common professional document types also require formality, such as other letters, memos, reports, proposals, agreements, and contracts. In such cases, you are expected to follow grammatical rules more strictly and make slightly elevated word choices, but not so elevated that you force your reader to look up rarely used words (they will not; they will just make up their mind about you being pretentious and a slight pain to deal with).

Writing in such a style requires effort because your grammar must be tighter and your vocabulary advanced. Sometimes a more elevated word choice—one with more syllables than perhaps the word that comes to mind—will elude you, requiring you to use a thesaurus (such as that built into MS Word in the Proofing section under the Review menu tab, or the Synonyms option in the drop-down menu that appears when you highlight and right-click a word). At the drafting stage you should, in the interests of speed-writing to get your ideas down nearly as fast as they come, go with the word that comes to mind and leave the synonym-finding efforts for the editing stage. Strictly maintaining a formal style in all situations would also be your downfall, however, because flexibility is also expected depending on the situation.

2. Casual Style in Writing

Your ability to gear down to a more casual style is necessary in any situation where you’re communicating with familiar people generally on your level and when a personable, conversational tone is appreciated, such as when writing to someone with basic reading skills (e.g., an EAL learner, as we saw in §2.2.3). In a routine email to a colleague, for instance, you would use the informal vocabulary exemplified in the semi-formal/common column of Table 2.2.3 above, including conversational expressions such as “a lot” instead of the more formal “plenty.” You would also use contractions such as it’s for it is or it has, would’ve for would have, and you’re for you are (see Table 5.3.2 for more contractions). Two paragraphs up from this one, the effort to model a more formal style included avoiding contractions such as you’ve in the first sentence, it’s in the third, and won’t and they’ll in the last, which requires a determined effort because you must fully spell out each word. While not a sign of disrespect, the more relaxed approach says to the reader “Hey, we’re all friends here, so let’s not try so hard to impress each other.” When an upper-level manager wants to be liked rather than feared, they’ll permit a more casual style of communication in their employees’ interactions with them, assuming that doing so achieves collegiality rather than disrespect.

Incidentally, this textbook mostly sticks to a more casual style because it’s easy to follow for a readership that includes international EAL learners. Instead of using the slightly fancy, three-syllable word “comprehend” in the middle of the previous sentence, for instance, “follow” gets the point across with a familiar, two-syllable word. Likewise, “casual” is used to describe this type of writing because it’s a six-letter, three-syllable word that’s more accessible to a general audience than the ten-letter, four-syllable synonym “colloquial.” These word choices make for small savings in character and word counts in each individual case, but, tallied up over the course of the whole book, make a big difference in size, tone, and general readability while remaining appropriate in many business contexts. Drafting in such a style is easy because it generally follows the diction and rhythms that come naturally in common conversation.

3. Slang Style in Writing

As the furthest extreme on the formality spectrum, slang and other informal means of communication, such as emojis, are generally unacceptable in business contexts for a variety of reasons. First, because slang is common in teen texting and social media, it appears immature, frivolous, out of place, confusing, and possibly even offensive in serious adult professional situations. Say someone emailed a car cleaning company with questions about their detailing service and received a reply that looks like it was texted out by a 14-year-old trying to sound “street,” such as:

Fo sho i set u up real good, well get yr car cleen smoove top 2 bottom – inside + out – be real lit when were done widdit, cost a buck fiddy for da hole d-lux package, so u down widdit erwat

The inquiring customer would have serious concerns about the quality and educational level of the personnel staffing the company, and, thus about the quality of work they’d do. The customer may even wonder if they’ll get their car back after giving them the keys. The customer will probably just give the company a pass and continue looking for one with a more formal or even casual style that suggests greater attention to detail and awareness of professional communication standards. A company rep that comes back with a response more like the following would likely assure the customer that their car is in good hands:

Absolutely, we can do that for you. Our White Glove service thoroughly vacuums and wet-vacs all upholstery, plus scrubs all hard surfaces with pro-grade cleaners, then does a thorough wash and wax outside. Your autobody will be like a mirror when you pick it up. Please let us know if you are interested in our $150 White Glove service.

Second, the whole point of slang is to be incomprehensible to most people, which is opposite to the goal of communication discussed in §1.3, especially in situations where you want to be understood by a general audience (see §2.2.3). As a deviation from accepted standards of “proper” vocabulary, grammar, punctuation, syntax, etc., slang is entirely appropriate in adolescent and subculture communication because it is meant to score points with an in-group that sets itself apart from the rest of polite society. Its set of codewords and nonstandard grammar is meant to confuse anyone not part of that in-group and would sound ridiculous if anyone else even tried to speak it, as when parents try to level with their teens in teen vernacular. Obviously, if slang is used in professional contexts where audiences just don’t know how to accurately translate the expressions, or they don’t even know about Urban Dictionary to help translate “a buck fiddy” in the above example as $150 rather than $1.50, the ensuing confusion results in all the expensive problems brought on by miscommunication.

In terms of the writing process, professionals should generally avoid slang style in almost all business situations, even if it’s what comes naturally because it leaves the writer too much work in the editing stage. If slang is your style, it’s in your best interests to bring your writing habits up to the casual level with constant practice. Perhaps the only acceptable situation where a slang-heavy style would be appropriate is if you’re on a secure texting or IM channel with a trusted colleague whom you’ve developed a correspondence rapport with, in which case that style is appropriate for the audience because they understand it, expect it, and appreciate it. It can even be funny and lighten up someone’s day.

The danger of expressing yourself in such a colourful style in email exchanges with that trusted friend-colleague when using company channels, however, is that they may be seen by unintended audiences. Say you have a back-and-forth exchange about a report you’re collaborating on, and you need to CC your manager at some point so that they are up to speed on your project (or someone else involved does this for you, leaving you no opportunity to clean up the thread of past emails). If your manager looks back at the atrocious language and sees offensive statements, your employment could be in jeopardy. You could just as easily imagine other situations where slang style might be advantageous, such as marketing to teens, but generally, it’s avoidable because it tends to deviate from the typical characteristics of good writing.

4. Emojis in Professional Writing?

Though emojis’ typical appearance in social media and texting places them at the informal end of the formality spectrum, their advantages in certain situations require special consideration along with some clarity about their current place in professional communication. Besides being easy to access on mobile device keyboards and favoured in social media communication especially among millennials, emojis are useful for helping clarify the emotional state of the message sender in a way that plain text can’t. They offer a visual cue in lieu of in-person nonverbals. A simple “thumbs up” emoji even works well as an “Okay, got it” reply in lieu of any words at all, so they can help save time for the busy professional. Interestingly, 2,500 years after Egyptian hieroglyphics fell out of use, pictographs are making a comeback! Emojis also go partway toward providing something of a universal language that allows people who speak different languages to communicate in a way that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.

However, the lack of precision in emojis can also cause confusion as they may be interpreted differently if the social and cultural context of the receiver differs enough from that of the sender (Pringle, 2018), not to mention differences in their emotional states. This means that emojis aren’t as universal as some claim they are, especially when used by correspondents who speak different languages (Caramela, 2018). Even between those who speak the same language, a smiley-face emoji added to a lightly insulting text message might be intended as a light-hearted jab at the receiver by the sender but might be read as a deeply cutting passive-aggressive dig by the receiver. The same text message said in person, however, comes with a multitude of nonverbal cues (facial expressions, eye movements, body movements, timing, voice intonation, volume, speed, etc.) that help the listener determine the exact intentions of the speaker—meanings that can’t possibly be covered by a little 2D cartoon character.

You can imagine plenty of other scenarios where emojis could backfire with dire consequences. A red heart emoji added to a business message sent by a male to a female colleague, though perhaps meant in the casual sense of the word “love” when we say, “I love what you did there,” might be taken as signalling unwanted romantic intentions. In the #metoo era, this is totally inappropriate and can potentially ruin professional partnerships and even careers. Be careful with emojis also in any situation involving buying or selling, since commercial messages can end up in court if meanings, intentions, and actions part ways. In one case, emojis were used in a text message signalling intent to rent an apartment by someone who reneged and was judged to be nonetheless on the hook for the $3,000 commitment (Pringle, 2017). As with any new means of communication, some caution and good judgment, as well as attention to notable uses and abuses that show up in the news or company policy directives, can help you avoid making potentially disastrous mistakes.

Though emojis may be meaningfully and understandably added to text/instant messages or even emails between familiar colleagues who have developed a light-hearted rapport featuring their use, there are several situations where they should be avoided at all cost because of their juvenile or frivolous social media reputation. It’s a good idea to avoid using emojis in business contexts when communicating with:

- Customers or clients

- Managers who don’t use emojis themselves

- Colleagues you don’t know very well

- Anyone outside your organization

- College instructors

- Older people who tend to avoid the latest technology

However, in any of the above cases, you would probably be safe to mirror the use of emojis after your correspondent gives you the green light by using them first (Caramela, 2018). Yes, emojis lighten the mood and help with bonding among workplace colleagues. If used excessively as part of a larger breakdown of decorum, as mocked in the accompanying Baroness von Sketch Show video short (CBC Comedy, 2017), they suggest a troubling lack of professionalism. Managers especially should refrain from emoji use to set an example of impeccable decorum in communications to the employees they supervise (CBC Comedy,2017).

Video: “Work Emails | Baroness von Sketch Show” by CBC Comedy [3:17] is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.Transcript and closed captions available on YouTube.

4.5.2: The 6 Cs of Style

Whether you’re writing in a formal or casual style, all good writing is characterized by the “6 Cs”:

- Clear

- Concise

- Coherent

- Correct

- Courteous

- Convincing

Six-C writing is good for business because it fulfills the author’s purpose and meets the needs of the audience by making communication understandable and impactful. Such audience-oriented writing is clearly understood by busy readers on the first pass; it doesn’t confuse them with ambiguities and requires them to come back with questions for clarification. It gets the point across in as few words as possible so that it doesn’t waste readers’ time with word count-extending filler. Good writing flows logically by being organized according to recognizable patterns, with sub-points connected by well-marked transitions. Six-C writing avoids confusing readers with grammar, punctuation, or spelling errors, as well as avoids embarrassing its author and the company they represent because it is flawlessly correct. It leaves the reader with a good feeling because it is polite, positive, and focuses on the reader’s needs. Six-C writing is persuasive because, with all the above going for it, it exudes confidence. The following sections explain these characteristics in greater detail with an emphasis on how to achieve Six-C writing at the drafting stage.

1. Clarity

Clarity in writing means that the words on the page are like a perfectly transparent window to the author’s meaning; they don’t confuse that meaning like the dirty, shattered window of bad writing or require fanciful interpretation like the stained-glass window of poetry. Business or technical writing has no time for anything that requires the reader to interpret the author’s meaning or ask for clarification. To the busy reader scanning quickly, bad writing opens the door for wrong guesses that, acted upon, result in mistakes that must be corrected later; the later the miscommunication is discovered and the further the mistakes spread, the greater the damage control required. Vague writing draws out the communication exchange unnecessarily with back-and-forth requests for clarification and details that should have been clear the first time. Either way, a lack of clarity in writing costs businesses by hindering personal and organizational productivity. Every operation stands to gain if its personnel’s writing is clear in the first place.

So much confusion from vague expressions can be avoided if you use hard facts, precise values, and concrete, visualizable images. For example:

- Instead of saying “a change in the budget,” “a 10% budget cut” makes clear to the reader that they’ll have to make do with nine of what they had ten of before.

- Instead of saying that a home’s annual average basement radon level is a cause for concern, be specific in saying that it is 220 Bq/m3 (for becquerels per cubic metre) so that the reader knows how far above Health Canada’s guideline level the home is and therefore the extent of remedial action required.

- Instead of saying that you’re rescheduling it to Thursday, be clear on what’s being rescheduled, what the old and new calendar dates and times are, and if the location is changing, too. If you say that it’s the 3 P.M. Friday meeting on May 25th being moved to 9 A.M. Thursday, May 31st, in room B349, participants know exactly which meeting to move where in their email program’s calendar feature.

- Always spell out months so that you don’t confuse your reader with dates in the “dd/mm/yy” or “mm/dd/yy” style; for instance, “4/5/18,” could be read as either April 5th or May 4th, 2018, depending on whether the author personally prefers one date form over the other or follows a company style in lieu of any universally accepted date style.

- Instead of saying at the end of an email, “Let’s meet to discuss,” and leaving the ball in your correspondent’s court to figure out a time and place, prevent the inevitable time-consuming back-and-forth by giving your available meeting time options (e.g., “9–10 A.M. Thursday, May 31st; 2–3 P.M. Friday, June 1st; etc.) in a bulleted list and suggesting a familiar place so that all your correspondent needs to do is reply once with their preferred meeting time from among those menu options and confirmation on the location.

- Instead of saying, “You’ve got a message,” being clear that Tia Sherman from the Canada Revenue Agency left a voicemail message at 12:48 P.M. on Thursday, February 8th, gives you the precise detail that you need to act on that information.

The same is true of vague pronouns such as its, this, that, these, they, their, there, etc. (see the demonstrative and indefinite pronouns, #6 and #9 in Table 4.4.2a) when it’s unclear what they’re referring to earlier in a sentence or paragraph. Such pronoun-antecedent ambiguity, as it’s called (with antecedent meaning the noun that the pronoun represents), can be avoided if you can spot the ambiguity that the reader would be confused by and use other words to connect them to their antecedents. If you say, for instance,

The union reps criticized the employer council for putting their latest offer to a membership vote.

Whether the offer is coming from the union, the employer, or possibly (but unlikely) both is unclear because their could go either way. You can resolve the ambiguity by using words like the former, the latter, or a shortened version of one of the names:

The union reps criticized the employer council for putting the council’s latest offer to a membership vote.

When pronouns aren’t preceded by the noun to which they refer, the good writer must simply define them. Though these additions extend the word count a little, the gains in clarity justify the expense.

2. Conciseness

Because the goal of professional writing, especially when sharing expertise, is to make complex concepts sound simple without necessarily dumbing them down, such writing should communicate ideas in as few words as possible without compromising clarity. The worst writing predictably does the opposite, making simple things sound complicated. This is a rookie mistake among some students new to college or employees new to their profession. Perhaps because they think they must sound “smart,” they use expressions that are their attempt at imitating the kind of writing that goes over their head with fancy words and complex, wordcount-extending sentence constructions, including the passive voice (see §4.3.4). Such attempts are usually smokescreens for a lack of quality ideas; if someone is embarrassed by how meagre their ideas are, they tend to dress them up to seem more substantial. Of course, their college instructors or professional audiences are frustrated by this kind of writing rather than fooled by it because it doesn’t help them find the clear meaning that they expect and seek. It just gets in the way and wastes their time until they resent the person who wrote it.

If the temptation to overcomplicate a point is uncontrollable at the drafting stage, it’s probably better to vomit it all up at this point just so that you can get everything out while knowing that you’ll be mopping it up by paring down your writing later (see §5.1). By analogy, a film production will overshoot with perhaps 20 takes of (attempts at) a single shot just so that it has plenty of material “in the can” to choose from when assembling the sequence of shots needed to comprise a scene during post-production editing. However, as you become a better writer and hone your craft, you’ll be able to resist those filler words and overcomplicated expressions at the drafting stage from having been so aggressive in chopping them out at the editing stage of the writing process so many times before. Of course, if you make a habit of writing concisely even at the drafting stage, you’ll minimize the amount of chopping work you leave yourself at the editing stage.

3. Coherence and Completeness

Coherence means that your writing flows logically and makes sense because it says everything it needs to say to meet your audience’s needs. The organizational patterns discussed in §4.1, outlining structures in §4.2, and paragraph organization in §4.4 all help to achieve a sense of coherence. The pronouns and transitions listed in Table 4.4.2a and Table 4.4.2b especially help to connect the distinct points that make up your bare-bones outline structure as you flesh them out into meaningful sentences and paragraphs, just as ligaments and tendons connect bones and tissues throughout your body.

4. Correctness

Correct spelling, grammar, mechanics, etc., should not be a concern at the drafting stage of the writing process, though they certainly must be at the end of the editing stage (see Ch. 5). As explained above in the §4.3 introduction above, speed-writing to get ideas down requires being comfortable with the writing errors that inevitably pockmark your draft sentences. The perfectionists among us will find ignoring those errors difficult, but resisting the temptation to bog yourself down by on-the-go proof-editing will pay off at the revision stage when some of those awfully written sentences get chopped in the end anyway. Much of the careful grooming during the drafting stage will have been a waste of time.

5. Courtesy

No matter what kind of document you’re writing and what you can expect your audience’s reaction to it to be, writing courteously so that your reader feels respected is fundamental to reader-friendly messages. Whether you’re simply sharing information, making a sales pitch, explaining a procedure, or doing damage control, using polite language helps ensure your intended effects—that your reader will be receptive to that information, will buy what you’re selling, will want to perform that procedure, or will be onboard with helping to fix the error. The cornerstone of polite language is obviously saying “the P-word” that you learn gets what you want when you’re 18 months old—because saying please never gets old when asking someone to do something for you, nor does saying thanks when they’ve done so—but there’s more to it than that.

Much of courtesy in writing involves taking care to use words that focus on the positive, improvement, and what can be done rather than those that come off as being negative, critical, pushy, and hung up on what can’t be done. If you’re processing a contract and the client forgot to sign and date it, for instance, the first thought that occurs to you when emailing to inform them of the error may go something like the following:

You forgot to sign and date our contract, so you’ve got to do that and send it to me a.s.a.p. because I can’t process it till I receive it signed.

Now, if you were the client reading this slightly angry-sounding, accusatory order, you would likely feel a little embarrassed and maybe even a little upset by the edgy, pushy tone coming through in negative words like forgot, do that, a.s.a.p., and can’t. That feeling wouldn’t sit well with you, and you will begin to build an aversion to that person and the organization they represent. (If this isn’t the first time you forgot to sign a contract for them; however, the demanding tone would be more justified or at least more understandable.) Now imagine you read instead a message that says, with reference to the very same situation, the following:

For your contract to be processed and services initiated, please sign, date, and return it as soon as possible.

You would probably feel much better about coming through with the signed contract in short order. You may think that this is a small, almost insignificant shift in meaning, but the difference in psychological impact can be quite substantial, even if it operates subconsciously. From this example you can pull out the following three characteristics of courteous writing.

a. Use the “You” View

Audience-oriented messages that address the reader directly using the pronouns you and your have a much greater impact when the message is positive or even neutral. Writing this way is a little counterintuitive, however, because when we begin to encode any message into words, we do so naturally from our own perspective. The sender-oriented messages that result from our perspective don’t register as well with readers because they use first-person personal and possessive pronouns (I, me, my, we, us, and our) that tend to come off as being self-involved. In the above case, the contract is shared by both parties, but saying “our contract” is a little ambiguous because it may be read as saying “the employer’s contract” rather than “your and my contract.” Saying “your contract,” however, entitles the reader with a sense of ownership over the contract, which sits much better with them.

The trick to achieving an audience-oriented message is to catch yourself whenever you begin writing from your perspective with first-person personal pronouns like I and my, and immediately flip the sentence around to say you and your instead. Simply changing the pronouns isn’t enough, though; in the above case, it involved changing the wording so that the contract is sent by you rather than received by me. Switching to the audience perspective takes constant vigilance and practice, even from seasoned professionals, but soon leads to an audience-oriented habit of writing that endears you more to your readers and leads to positive results. An added benefit to habitually considering your audience’s perspective is that it makes you more considerate, sympathetic, and even empathetic, improving your sense of humanity in general.

The flip side of this stylistic advice is to use the first-person pronouns (I, we, etc.) as seldom as possible, which is true, but obviously, you can’t do without these entirely—not in all situations. When it’s necessary to say what you did, especially when it comes to negative situations where representing your perspective and accepting responsibility is the right thing to do, not using the first-person pronouns will result in awkward stylistic acrobatics. Simply use the audience-oriented “you” view and sender-oriented first-person personal pronouns when appropriate.

b. Prioritize Audience Benefits

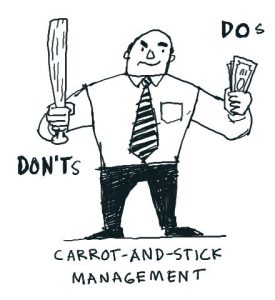

Whenever you need to convince someone to do something, leading with a positive result—what the reader will get out of it for their effort—followed by the instruction has a much better chance of getting the reader on board. Notice in the two example sentences above that the reader-hostile version places the demand before the result, whereas the improved, reader-friendly version places the result before the (kindly worded) demand. This simple organizational technique of leading with the audience benefits works because people are usually more motivated by the carrot (reward) than the stick (consequence), and dangling the carrot attracts the initial interest necessary to make the action seem worthwhile. It’s effective because it answers what we can always assume the reader is wondering: “What’s in it for me?”

Messages that don’t immediately answer that question and instead lead with the action, however, come from a sender-oriented perspective that initially turns off the reader because it comes off as being demanding in tone. Obviously, some situations require a demanding tone, as when being nice gets no results and necessity forces you to switch to the stick. Again, leading with the demand may be what occurs to you first because it addresses your immediate needs rather than your reader’s, but making a habit of flipping it around will give your writing greater impact whenever you give direction or issue instructions.

c. Focus on Future Positive Outcomes

Focusing on what can be done and improvement sits better with readers than focusing on what can’t be done and criticism. In the above case, the initial rendering of the problem focused on blaming the reader for what they did wrong and on the impasse of the situation with the contract. The improved version corrects this because it skips the fault-finding criticism and instead moves directly to what good things will happen if the reader does what needs to be done. The reader of the second sentence will associate you with the feeling of being pleased by the taste of the carrot rather than smarting from the whack of the stick.

The flip side of this stylistic preference involves replacing negative words with positive words unless you have an important reason for not being nice. Being vigilantly kind in this way takes some practice, not because you’re a bad person but because your writing habits may not reflect your kindness in writing. Vigilance here means being on the lookout whenever you’re tempted to use the following words or their like in situations that aren’t too dire:

- awful

- bad / badly

- can’t / cannot

- crappy

- deny

- disappointing

- don’t

- dumb

- fail / failure

- fault / faulty

- hate

- hopeless

- horrible

- impossible

- lose / loser

- never

- no/nope

- nobody

- not

- poor / poorly

- reject

- sorry

- stupid

- substandard

- terrible

- unfortunate / unfortunately

- won’t

- worthless

Rather than shaming the author of a report by saying that their document is terrible, for instance, calling it “improvable” and pointing out what exactly they can do to fix it respects the author’s feelings and motivates them to improve the report better than what you really want to say in a passing moment of disappointment. Of course, taking this advice to its extreme by considering it a hard-and-fast rule will obviously destroy good writing by hindering your range of expression. You’ll notice that this textbook uses many of the above words when necessary. In any case, make it a habit to use positive words instead of negative ones if it’s clear that doing so will result in a more positive outcome.

On its own, translating a single sentence like the one exemplified above will likely not have a lasting effect; over time, however, a habitual focus on negative outcomes and the use of negative language will result in people developing a dislike for dealing with you and, by association, the company you represent. If you make a habit of writing in positive words most of the time and use negative words only in situations where they’re necessary, on the other hand, you stand a good chance of being well liked. People will enjoy working with or for you, which ensures continued positive relations as well as opens the door to other opportunities.

6. Convincing and Confident

When all the other aspects of style described above are working in concert, and when the information your writing presents comes from sound sources, it naturally acquires an air of confidence that is highly convincing to readers. That confidence is contagious if you are rightfully confident in your information or argument, decisive in your diction, and avoid lapsing into wishy-washy, noncommittal indecision by overusing weak words and expressions like:

- almost

- approximately

- basically

- blah

- close to

- could (have)

- -esque

- -ish

- kind of / kinda

- may / maybe

- meh

- might

- probably

- roundabout

- somewhat

- sort of / sorta

- should (have)

- thereabouts

- usually

- we’ll see

- whatever

- whenever

- whichever

- -y (e.g., orange-y)

These timid, vapid words are a death to any sales message especially. This is not to say that your writing can’t err toward overconfidence through lapses in judgment or haughtiness. If you apply the same rigour in argument and persuasion that you do in selecting quality research sources that are themselves well reasoned, however, by considering a topic holistically rather than simplistically for the sake of advancing a narrowminded position, it’s easy to get readers to comprehend your information share, follow your instruction, buy what you’re selling, and so on.

Key Takeaway

Drafting involves writing consistently in a formal, casual, or informal style characterized by the “Six Cs”: clarity, conciseness, coherence, correctness, courtesy, and conviction.

Exercises

- Assemble a Six-Cs scoring rubric for assessing professional writing using the descriptions throughout §4.5.2. In the highest-achievement column, list in point-form the attributes of each characteristic. In the columns describing lesser and lesser levels of achievement, identify how those expectations can fall apart. For help with the rubric form, you may wish to use Rubistar’s writing rubric template.

- Find examples of past emails or other documents you’ve written that make you cringe, perhaps even high school essays or reports. Identify instances where they are unclear, unnecessarily longwinded, incoherent (lacking both a clear organizational pattern and transitions that drive the argument along), rife with writing errors, rude, and/or unconvincing. Assess and score those specimens using your Six-Cs rubric from Exercise 1 above. Begin to think of how you would improve them (a future exercise in Ch. 5 will ask you to revise and proof-edit them).

- Find a professionally written document, perhaps from a case study in another class. Assess it using the same Six-Cs scoring rubric.

- Speed-write a written assignment that you’ve been recently assigned in one of the other courses in your program. If you’re not fast at typing (or even if you are and want to try something new), you may start by recording your message into your smartphone’s or computer’s voice recorder app or program and then transcribe it. Ensure that your style hits five of the six style Cs (clarity, conciseness, coherence, courtesy, and conviction) as you write and most definitely do not correct as you go.