4.3: Forming Effective Sentences

Learning Objectives

3. Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Once you’ve put words on the screen with research material and outlined the shape of your content with point-form notes, building around that research and fleshing out those notes into correct English sentences should be quick and dirty composition—“quick” because speed-typing helps get your thoughts down almost as soon as they occur to you, and “dirty” because it’s fine if those typed-out thoughts are garbage writing rife with errors. A talented few might be able to think and draft in perfectly correct sentences, but that’s not our goal at this stage.

As long as you clean it all up later, what’s important during the drafting stage is that you get your ideas down quickly to avoid losing any in the nitty-gritty bog of perfectionist composition. If you’re still working on speeding up your typing (it can be a lifelong process!), however, consider using your smartphone’s voice recorder to capture what you want to say out loud, then transcribe it into somewhat proper sentences by playing it back sentence by sentence. Correcting that writing as you draft is a waste of time because, in the first substage of editing (see §5.1), you may find yourself deleting whole sentences and even paragraphs that you meticulously perfected at the drafting stage. As we shall see in Chapter 5, scrupulously proof-editing for spelling, grammar, and mechanical errors—as well as the finer points of style—should be one of your final tasks in the whole writing process. At this stage, however, you at least need some sentences to work with.

Fashioning effective sentences requires an understanding of sentence structure. Now, the eyes of many native English speakers glaze over as soon as English grammar terminology rears its head. But think of it this way: to survive as a human being, you must take care of your health, which means occasionally going to the doctor for help with the injuries and conditions that inevitably afflict you; to understand these, you listen to your doctor’s explanations of how they work in your body, and you add to your vocabulary anatomical terms and processes—words you didn’t need for those processes to function when you were healthy. Now that you need to work to improve your health, however, you need that technical understanding to know how exactly to improve. It’s likewise worth learning grammar terminology because writing mistakes undermine your professionalism, and you won’t know how to write correctly, such as where to put punctuation and where not to, if you don’t know basic sentence structure and the terminology we use to describe it. Trust me, we’ll be using it often throughout this chapter and the next. Many native English speakers who say, “I don’t know what the rule’s called, but I know what looks right” actually can improve their writing if they understand more about how it works. Pay close attention throughout the following introductory lesson on sentence structure and variety especially if you’re not entirely confident in your knowledge of grammar.

- 4.3.1: Four Sentence Moods

- 4.3.2: Four Sentence Varieties

- 4.3.3: Sentence Length

- 4.3.4: Active- vs. Passive-voice Sentences

4.3.1: Sentence Structure and the Four Moods

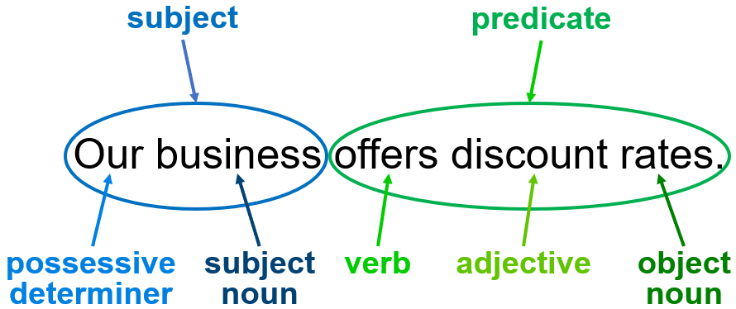

Four basic sentence moods (or types) help you express whatever you want in English, as detailed in Table 4.3.1 below. The most common sentence mood, the declarative (a.k.a. indicative), must always have a subject and a predicate to be grammatically correct. The subject in the grammatical sense (not to be confused with the topic in terms of the content) is the doer (actor or performer) of the action. The core of the subject is a noun (person, place, or thing) that does something, but this may be surrounded by other words (modifiers) such as adjectives (words that describe the noun), articles (a, an, the), possessive determiners (e.g., our, my, your, their), quantifiers (e.g., few, several), etc. to make a noun phrase. The core of the predicate is a verb (action), but it may also be preceded by modifiers such as adverbs, which describe the action in more detail, and followed by an object, which is the thing (noun or noun phrase) acted upon by the verb. If you consider the sentence Our business offers discount rates, you can divide it into a subject and predicate, then further divide those into their component parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.):

Our business offers discount rate.

- Subject = Our business

- Possessive determiner = Our

- Subject noun = business

- Predicate = offers discount rates

- verb = offers

- adjective = discount

- object noun = rates

Subjects and predicates can also grow with the addition of other types of phrases (e.g., prepositional, infinitive, participial, and gerund) (Cimasko, 2013; Purdue OWL, 2010, 2011a, 2011b; Darling, 2014a) to clarify meaning even further. As large as a sentence can get with the addition of all these parts, however, you should always be able to spot the core noun of the subject and main verb of the predicate. Sentences that omit either are called fragments and should be avoided (or fixed later, as we’ll see in §5.2) because they confuse the reader, being unclear about who’s doing what.

Table 4.3.1: Four Sentence Moods

| Sentence Mood | Structure and Use | Example and Breakdown |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Declarative |

|

We quickly updated our computer systems.

Subject: We (pronoun)

|

| 2. Imperative |

|

Please update our computer systems quickly.

The subject (e.g., You) that would be identified in the declarative form is always assumed (never included). |

| 3. Interrogative |

|

Can you please update our computer systems quickly? |

| 4. Exclamatory |

|

Thanks for updating our computer systems so quickly! |

| 5. Subjunctive |

|

If you were to update our computer systems this weekend, we would be incredibly grateful. |

A declarative sentence with just a straightforward subject and predicate is a simple sentence expressing a complete thought. If all sentences were simple, such as you might see in a children’s reader (e.g., The dog’s name is Spot. Spot fetched the stick. He is a good boy sometimes. etc.), we would say that this is a choppy or wooden style of writing. We avoid this result by adding subject-predicate combinations together within a sentence to clarify the relationships between complete thoughts. Such combinations make what’s called compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences. Before we break down these sentence varieties, however, it’s important to know what a clause is.

4.3.2: Four Sentence Varieties

We keep our readers interested in our writing by using a variety of sentence structures that combine simple units called clauses. These combinations of subjects and predicates come in two types:

- An independent or main clause can stand on its own as a sentence like the simple declarative ones broken down in §4.3.1.

- A dependent or subordinate clause begins with a subordinating conjunction like when, if, though, etc. (Darling, 2014b) and needs to either precede or follow a main clause to make sense. Like a domesticated dog that strays from their owner, a dependent clause can’t survive on its own; if it tries anyway, a subordinate clause posing as a sentence on its own is just a fragment (see §5.2) that confuses the reader.

An independent clause on its own plus combinations of these two types of clauses make up the four varieties of sentences we use every day in our writing. Two or more independent clauses joined together with a comma and coordinating conjunction (see Table 4.3.2a below for the seven of them, represented by the mnemonic acronym fanboys) or semicolon (;) make a compound sentence (Darling, 2014c, 2014d, 2014e). When combined with a main clause by a subordinating conjunction, a subordinate clause makes a complex sentence (Darling, 2014e). That subordinating conjunction (see a variety of them in Table 4.3.2a below) establishes the relationship between the subordinate and main clause as one of time, place, or cause and effect (Simmons, 2012). When a subordinate clause precedes the main clause, a comma separates it from the main clause (as in this sentence to this point), but a comma is unnecessary if the subordinate clause follows the main clause (as in this sentence from but onwards; notice that a comma doesn’t come between unnecessary and if).

Table 4.3.2a: Coordinating and Subordinating Conjunctions

| Coordinating Conjunctions | Subordinating Conjunctions |

|---|---|

| for and nor but or yet so |

After Although As As if As long as As though Because Before Even if Even though If If only In order that Now that Once Provided that Rather than Since So that Than That Though Till UnlessUntil When Whenever Where Whereas Wherever Whether While |

You can combine compound and complex sentences into compound-complex sentences, like the sentence that precedes this one, though you should keep these streamlined so your wordcount (29 words in the sentence just before Table 4.3.2a, not including the parenthetical asides) doesn’t make comprehension difficult. We’ll return to the question of length in the following subsection (§4.3.3), but let’s focus now on how these four sentence varieties are structured.

Table 4.3.2b: Four Sentence Varieties

| Sentence Variety | Structure & Use | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Simple |

|

We quickly updated our computer systems.

Subject: We (noun)

Productivity increased 35% by the end of the week. |

| 2. Compound |

|

We updated our computer systems on the 12th, and productivity increased 35% by the end of the week.

We updated our computer systems on the 12th; productivity increased 35% by the end of the week. We updated our computer systems on the 12th, yet productivity didn’t increase the next day. We updated our systems on the 12th, but gains in productivity weren’t seen till the end of the week. If the subject is the same in both clauses, omit both the comma that precedes the conjunction, as well as the repeated subject: We updated our computer systems and increased our productivity 35% by the end of the week. (The subject “we” is common to both clauses, so the second “we” [in “we increased”] is omitted, making this a single independent clause with coordinated verbs [“updated” and “increased”] rather than two coordinated clauses.) |

| 3. Complex |

|

After we updated our computer systems on the 12th, productivity increased 35% by the end of the week.

When the subordinate clause precedes the main clause, a comma separates them, as in the example above. When the subordinate clause follows the main clause, a comma is unnecessary, as in the example below. Productivity increased by 35% in a week after we updated our computer systems on the 12th. However, if the subordinate clause strikes a contrast with the main clause preceding it, a comma separates them: Productivity increased by 35%, although it took a week after updating our systems to see those gains. |

| 4. Compound-complex |

|

When we updated our computer systems on the 12th, productivity increased 35% by the end of the week, but the systems needed updating again within the month to restore productivity increases. (31 words)

Introductory dependent clause + independent clause + independent clause |

Combinations of sentence moods and varieties are all possible, so we have many hybrid sentence structures available to express our thoughts. For instance, an introductory subordinate clause can precede an interrogative main clause:

If you are available to update our computer systems on the 12th, can you please sign and return the attached contract at your earliest convenience?

Combining clauses to communicate your ideas is a skill like any other that requires practice, which you do whenever you draft a message. The more you do it, the better you get at it and the easier it becomes. It’s essential to your professional success that you become good at it, however, because your reading audiences will become frustrated with you if you cannot put sentences together effectively. Worse, disorganized sentences betray a scattered mind. Rather than stop to help you, your readers are more likely to avoid you because they have no time for the lack of professionalism signalled by poor writing and the miscommunication it leads to. Before we return to the subject of clauses when we examine how to correct sentence errors (see §5.2), we should stop to consider the issue of sentence length brought up in our discussion of compound-complex sentences above.

4.3.3: Sentence Length

What is the appropriate length for a sentence? Ten words? Twenty? Thirty? The answer will always be: it depends on what you expect your audience to be able to handle and what you need to say to express a complete thought to them. A children’s primer sticks to simple sentences of 5-7 concise words because children learning how to read will be stymied by anything but the simplest possible sentences. A 30-page market analysis report aimed at business executives with advanced literacy skills, on the other hand, will have sentences of varying lengths, perhaps anywhere from 5 to 45 words. The longer sentences with plenty of subordination and compounding will hopefully be rare because too many sentences of 45 words will exhaust a reader’s patience and compromise comprehension with complexity. Too many five-word sentences will insult the reader’s intelligence, but they play well as punchy follow-ups that conclude paragraphs full of long sentences. Ultimately, you should treat your audience to a variety of sentence lengths (Nichol, 2016).

Sentences in most business documents should average around 25 words, which you may consider your baseline goal for sentence length. There’s nothing wrong with sentences shorter than that if they don’t sacrifice clarity in achieving conciseness. There’s also nothing wrong with writing the odd 40-word sentence if it takes that many words to express a complete (and probably complex) thought when anything less would again sacrifice clarity. In all cases, however, you must consider your intended audience’s reading abilities.

If the goal of communication is to plant an idea hatched in your brain undistorted into someone else’s brain, don’t make length a distorting factor. Sentences can technically go on forever with compounding and subordination, yet still be grammatically correct because a long sentence is not the same as a run-on (Darling, 2014f). But too many 40-word sentences in a row will betray a lack of skill in concision and respect for audience attention spans. Ultimately, no hard and fast rules for sentence length keep us from writing sentences that are as short or long as they need to be, but there is such a thing as too much if length becomes a barrier to understanding.

4.3.4: Active- vs. Passive-voice Sentences

When your style goal is to write clear, concise sentences, most of them should be in the active voice rather than passive. Voice in this grammatical sense concerns the order of words around the main verb and whether the verb requires an additional auxiliary (helper) verb. We use two voice varieties:

- Active-voice clauses are easy and straightforward because they begin by identifying the subject (the doer of the action), then say what the subject does (the verb or action) without an auxiliary verb, and end by identifying the object (the thing acted upon) if the verb is transitive (takes an object). The simple sentence we saw in Table 4.3.2b above follows this easy subject-verb-object order.

- Passive-voice clauses, on the other hand, reverse this subject-verb-object order to place the object first, follow with a passive verb phrase (more on that below), and optionally end with the doer of the action in a prepositional phrase starting with by.

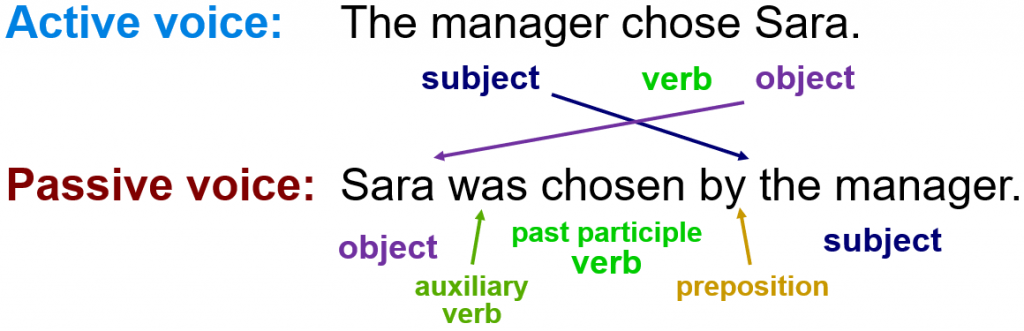

Consider the following example simple sentences that say the very same thing in both voices, one in the subject-verb-object active voice, the other in the object-verb-subject passive voice:

We can further divide the passive voice into sentences that identify the doer of the action and those that don’t:

Active Voice: The manager chose Sara

- Subject = The manager

- Verb = chose

- Object = Sara

Passive Voice: Sara was chosen by the manager.

- Object = Sara

- Auxiliary verb = was

- Past participle verb = chosen

- Preposition = by

- Subject = the manager

We can further divide the passive voice into sentences that identify the doer of the action and those that don’t:

Table 4.3.4: Comparison of Active- and Passive-voice Sentences

| Voice | Examples | Structural Breakdown |

|---|---|---|

| Active Voice | The manager chose Sara. | Subject (doer): The manager Verb: chose (past tense) Object: Sara |

| Passive Voice | Sara was chosen by the manager. | Object: Sara Verb phrase: was chosen (form of to be + past participle) Preposition: by Subject (doer): the manager |

| Passive Voice | Sara was chosen. | Object: Sara Verb phrase: was chosen (form of to be + past participle) |

From this you can see that the two necessary markers of a passive-voice construction are:

- A form of the verb to be as an auxiliary (helper) verb paired with the main verb, usually right before it. The auxiliary verb determines the tense of the main verb:

- Past forms of to be: was, were

- Sara was chosen. We were chosen.

- Past perfect form of to be: had been

- Sara had been chosen.

- Present forms of to be: am, are, is

- Sara is chosen. You are chosen. etc.

- Future form of to be: will be

- Sara will be chosen.

- Future perfect form of to be: will have been

- Sara will have been chosen by then.

- Past forms of to be: was, were

- The main verb in its past participle form.

- Some verbs, like to choose, will have an n added to the past-tense form to make the past participle (chosen).

- Other verbs’ past participle form is the same as their past-tense form, such as to promote, which forms promoted in both the simple past tense and past participle; e.g., the active-voice sentence The manager promoted Sara becomes the passive Sara was promoted.

Be careful, however: a sentence having a form of the verb to be in it doesn’t necessarily make it passive; if the form of the verb to be is the main verb and it isn’t accompanied by an auxiliary, such as in the sentence Sara is thrilled, then the form of the verb to be is what’s called a copular verb, which functions as an equals sign (“Sara = thrilled”). And though the prepositional phrase “by [the doer of the action]” may also signal a passive voice, the fact that identifying the doer is optional means that having the word by in the sentence doesn’t guarantee that it’s in the passive voice. For instance, the active-voice sentence Sara won the promotion by working hard all year is in the active voice and uses by in a manner unrelated to voice type.

Readers prefer active-voice (AV) verbs in most cases because AV sentences are more clear and concise—clear because they identify who does what (the manager chose someone in the Figure 4.3.4 and Table 4.3.4 example AV sentences), and concise because they use as few words as possible to state their point. Passive-voice (PV) verbs, on the other hand, say the same thing with more words because, in flipping the order, they must add an auxiliary verb (was in the above case) to indicate the tense—as well as the preposition by to identify the doer of the action, totalling six words in the above example to say what the AV said in four. If the PV didn’t add these words, then simply flipping the order of words to say “Sara chose the manager” would turn the meaning of the sentence on its head.

You can make the PV sentence shorter than even the AV one while still be grammatically correct, however, by omitting the doer of the action, as in the second PV example given in Table 4.3.4. The catch is that doing this makes the sentence less clear than the AV version. AV clauses cannot just omit the subject because they would be grammatically incorrect fragments: Chose Sara, for instance, would make no sense on its own as a sentence, whereas Sara was chosen would, even though it begs the question, “By whom?” PV sentences are thus either vague or wordy compared with AV, which are qualities exactly opposite our stylistic ideal of being clear and concise.

Now, before you fall into the trap of thinking that this is some kind of advanced writing technique just because it takes considerable explanation to break it all down, it’s worth stopping to appreciate that you speak AV sentences all day, every day, as well as naturally slip into the PV for strategic purposes probably about 5-10% of the time, even if you didn’t have the terminology to describe what you were doing until now. You just do it to suit your purposes. Sometimes those purposes are contrary to the ideals of good writing, such as when people lapse into the passive voice—even if they don’t realize it—because they think it makes their writing look more sophisticated and scientific sounding, or they just want to write complicated, wordcount-extending sentences to make up for an embarrassing lack of things to say. In such cases, discerning readers aren’t fooled; they know what the writer is doing and are frustrated by having to hack and slash through vague and wordy verbiage to rescue what meagre point the author meant to make. Please (please!) don’t use the PV in this way.

Appropriate uses of the PV, on the other hand, are few. You can use it to:

- Emphasize the object of the verb (the person, place, or thing acted upon) for variety amidst a majority of AV sentences that prioritize the subject. In the Table 4.3.4 example, saying “Sara was chosen” in the PV focuses the audience’s attention on the object, Sara, by putting her first, rather than on the manager as the doer of the action. Indeed, the manager’s role in the choosing might be so irrelevant that they can exit the sentence altogether, perhaps because the context of the conversation makes it so obvious that it goes without saying.

- Hide the doer of the action. If Sara was chosen for a promotion over her colleagues, saying “Sara was chosen” in the PV focuses on her accomplishment while drawing attention entirely away from the manager. Perhaps you don’t want the people who were passed up for promotion to know who exactly they should direct their resentment at. Using the PV, in this case, makes the choice of Sara sound objective, like anyone would have chosen her for this promotion because she really deserved it. PV is often used in this way as a public relations strategy to control the message. This use of the PV can be quite problematic when used as cover for the doer (see #3 below), however, as we see in the rhetoric surrounding gender violence. Rephrasing a sentence like John beat Mary as Mary was beaten shifts the focus of violence to the victim rather than the perpetrator by dropping the latter from the conversation altogether. We need to target the perpetrators of gender violence (mainly men and boys), however, as the root of the problem if we hope to reduce and eliminate the harm done to women and girls, as explained in the accompanying video lecture (TEDx Talks, 2013, 4:15-6:50).

Video: “Violence against women—it’s a men’s issue: Jackson Katz at TEDxFiDiWomen” by TEDx Talks [19:07] is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.Transcript and closed captions available on YouTube.

- Avoid accepting responsibility. In answer to an irate parent’s question, “Who broke this glass?” a fibbing two-year-old might say, “It was just broken when I got here.” We learn early—long before we even know how to read and write—how to cover up for our mistakes with this trick of language. Even dodging politicians will say, “Clearly, mistakes were made,” which makes it sound as if the blunders were made by unknown actors, rather than the policy-makers themselves, as the more honest alternative in the AV, “Clearly, we made mistakes,” would make clear (Benen, 2015).

- Indicate that you don’t actually know who the doer is. Saying “A charitable donation was left in our mailbox” in the PV is stylistically appropriate if you want to focus on the donation and don’t know who left it, whereas “Someone left a charitable donation in our mailbox” is an AV equivalent that focuses more on the anonymity of the benefactor.

- State a general rule or principle without singling anyone out. Declaring that “Returns must be accompanied with a receipt in order to receive a refund” in the PV is a more tactful, less authoritarian and negative way of saying “You can’t get a refund without a receipt” in the AV.

- Follow a stylistic preference for PV sentences in some scientific writing. Saying “The titration was performed” or “a lean approach is recommended” sounds more objective—albeit a little unnatural, especially when nearly every sentence is in the PV rather than the 5-10% we are used to in conversation—compared with the more subjective-sounding AV statements “I performed the titration” or “I recommend a lean approach.” (See the following paragraph for a solution to this predicament.)

We’re focusing on AV and PV now at the drafting stage of the writing process because favouring the AV is a stylistic requirement in business and technical writing where clarity and conciseness are especially valued, but it’s also possible to sound objective in the AV in technical writing. You can, for instance, identify the role of the doer rather than an individual person by name or first-person pronoun. Sentences like “The lab technician performed the titration” or “This report recommends a lean approach” still sound objective in the AV and therefore have an advantage over the PV.

We will return to the issue of AV vs. PV in §5.4 on editing for style, but if you train yourself to write in the AV rather than PV as a habit and only use PV when it’s justified by strategic advantage or necessity, you can save yourself time in both the drafting and editing stages of the writing process. For further explanation of the AV vs. PV and example sentences, see:

- Active and Passive Voice (Toadvine, Brizee, & Angell, 2011)

- Passive Voice: When to Use It and When to Avoid It (Corson & Smollett, 2007)

Key Takeaway

Flesh out your draft by expanding outlined points into full, mostly active-voice sentences that are varied in length and style as simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex structures correct in their declarative, imperative, interrogative, exclamatory, or subjunctive mood.

Exercises

- Re-read the paragraphs above in this chapter section and pull out examples of declarative and imperative sentences, as well as simple, compound, and complex sentences (but not those given as examples when illustrating each form, in or out of the tables). In your document, write headings in bold for each sentence type and variety, then copy and paste at least a few examples under each.

- Take the outline you drafted for the email if you did Exercise 2 at the end of §4.2 (or any other outlined message that you intend to write) and expand those points into a message that includes at least one example of each of the four sentence types and varieties covered in this section.

- Copy and paste at least five active- and five passive-voice main clauses from sentences in the paragraphs of this chapter section (besides those used as examples) into a document and break them down to identify their subject, main verb (or passive verb phrase, including the auxiliary verb) and object in the manner demonstrated in Table 4.3.4. Under each, rewrite the five active-voice clauses as passive-voice sentences, and each of the passive-voice clauses as active-voice sentences.