3.5: Documenting Sources in APA, MLA, or IEEE Styles

Learning Objectives

6. Integrate and document information using commonly accepted citation guidelines.

To prove formally that we’ve done research, we use a two-part system for documenting sources. The first part is a citation that gives a few brief pieces of information about the source right where that source is used in our document and points to the second part, the bibliographic reference at the end of the document. This second part gives further details about the source so that readers can easily retrieve it themselves. Though documenting research requires a little more effort than not, it looks so much better than including research in a document without showing where you got it, which is called plagiarism. Before focusing further on how to document sources, it’s worthwhile to consider why we do it and what exactly is wrong with plagiarism.

- 3.5.1: Academic Integrity vs. Plagiarism

- 3.5.2: Citing and Referencing in APA Style

- 3.5.3: Citing and Referencing in MLA Style

- 3.5.4: Citing and Referencing in IEEE Style

- 3.5.5: Citing Images and Other Media

3.5.1: Academic Integrity vs. Plagiarism

Academic integrity basically means that you do your work yourself and formally credit your sources when you use research, whereas plagiarism is cheating. Students often plagiarize by stealing the work of others from the internet (e.g., copying and pasting text, or dragging and dropping images) and dumping it into an assignment without quoting or citing; putting their name on that assignment means that they’ve dishonestly presented someone else’s work as their own. Lesser violations involve not quoting or citing properly. But why would anyone try to pull one over on their instructor like this when instructors award points for doing research? If you’re going to do your homework, you might as well do it right by finding credible sources, documenting them, and getting credit for doing so rather than sneak your research in as if you’ll get points for originality, for coming up with professional-grade material yourself, and end up getting penalized for it. But what makes plagiarism so wrong?

Plagiarism is theft, and bad habits of stealing others’ work in school likely begin as liberal attitudes towards intellectual property in our personal lives, but often develop into more serious crimes of copyright or patent violations in professional situations with equally serious financial penalties or destruction of reputations and earning power. The bad habits perhaps start from routines of downloading movies and music illegally because, well, everybody does it and few get caught (Helbig, 2014), or so the thinking goes; the rewards seem to outweigh the risks. But when download bandits become professionals, and are tasked with, say, posting on their company website some information about a new service the company is offering, their research and writing procedure might go something like this:

- They want their description of the service to look professional, so they Google-search to see what other companies offering the same service say about it on their websites. So far, so good.

- Those other descriptions look good, and the employee can’t think of a better way to put it, so they copy and paste the other company’s description into their own website. Here’s where things go wrong.

- They also see that the other company has posted an attractive photo beside their description, so the employee downloads that and puts it on their website also.

The problem is that both the text and photo were copyrighted, as indicated by the “All Rights Reserved” copyright notice at the bottom of the other company’s webpage. Once the employee posts the stolen text and photo, the copyright owner (or their legal agents) find it through a simple Google search, Google Alerts notification, reverse image search, or digital watermarking notification (Rose, 2013). The company’s agents send them a “cease & desist” order, but they ignore it and then find that they’re getting sued for damages. Likewise, if you’re in hi-tech R&D (research and development), help develop technology that uses already-patented technology without paying royalties to the patent owner, and take it to market, the patent owner is being robbed of the ability to bring in revenue on their intellectual property themselves and can sue you for lost earnings. Patent, copyright, and trademark violations are a major legal and financial concern in the professional world (SecureYourTrademark, 2015), and acts of plagiarism have indeed ruined perpetrators’ careers when they’re caught, which is easier than ever (Bailey, 2012).

Every college has its own academic integrity policy that helps you avoid the consequences of plagiarism. Fanshawe College’s policy, for instance, defines an academic offence as follows:

“Obtaining or attempting to obtain an unfair advantage or credit for academic work for oneself or others by dishonest means” (Policy A136, Fanshawe College, 2021).

This means that successfully cheating – or even trying to cheat – is considered an offence. As mentioned earlier, we are committing an offence ourselves if we plagiarise or copy off someone. However, if we help someone else to cheat (let’s say by lending them our work), we are still committing an offence because we have assisted an offence in occurring.

If you keep two key concepts in mind: ‘unfair advantage’ and ‘dishonest means’, you’ll be able to see why certain actions and behaviours are considered to be Academic Offences when we look at the list of eleven Academic Offences in the next module.

It’s important to understand that both intentional and unintentional actions and behaviour can result in Academic Offences. It is often very clear when Academic Offences have occurred intentionally: perhaps a student intended to cheat on a test, or perhaps they submitted an assignment as their own, knowing that they did not do the work.

Intentional Academic Offences often result in the application of penalties which are disciplinary measures. Examples of unintentional Academic Offences include:

- improper citation in an assignment by a student not familiar with citing requirements,

- providing a completed assignment to a friend, not realizing that they may submit it as their own work, and

- uploading assignments to course content-sharing sites like Course Hero, not realizing that students may download the assignments and submit them as their own.

Unintentional Academic Offences often result in Warnings being issued so that students become aware that those actions and behaviours are not acceptable. Warnings are intended to be learning opportunities. Penalties would be applied if actions and behaviours continue after a Warning has been issued. Fanshawe’s Academic Integrity policy, for example, outlines eleven academic offences:

- The student commits plagiarism which means taking credit for another person’s work.

- The student acts to assist or facilitate an Academic Offence.

- The student misrepresents the reasons for a missed evaluation or deadline extension.

- The student allows another person to complete the student’s academic work, excluding quizzes, tests, and exams.

- The student copies from another person during a quiz, test, or exam.

- The student participates in activities, in person or electronically, that are not permitted in the preparation or completion of academic work.

- The student uses materials, resources, or technologies that are not permitted in the preparation or completion of academic work.

- The student possesses or uses materials, resources, or technologies that are not permitted in a quiz, test, or exam.

- The student improperly obtains any evaluation prior to the date and time scheduled for the evaluation.

- The student alters or falsifies academic records in any way or submits false documentation for academic purposes.

- The student allows another person to take a quiz, test, or exam in the student’s place.

Fanshawe’s penalties for plagiarizing increase with each offence. Penalties are disciplinary measures that are applied depending on the frequency and severity of Academic Offences. The following Penalties can be applied when any of the 11 Academic Offences occur:

- Re-do Work: the student is required to re-do the academic work for either full or reduced marks by a due date specified by the Course Instructor.

- Mark of Zero: a mark of zero is assigned to compromised portions of the quiz, test, exam, or assignment, or a mark of zero is assigned to a quiz, test, exam, or assignment in its entirety.

- Fail Course: an automatic grade of ‘F’ for the course in which the Academic Offence occurred.

- Suspension: the student is suspended from the College for the remainder of the term, for the remainder of the term plus one to two full terms, or the remainder of the term plus three full terms, which would be a complete academic year. The student would be permitted to return to the College and resume their studies when the Suspension has lapsed.

- Expulsion: the student is expelled from the College, and a minimum of five years would have to lapse before the student could reapply for admission (Academic Integrity at Fanshawe College, 2022).

For more information about academic integrity at Fanshawe, and for additional resources, consult the following:

- Academic Integrity website at Fanshawe’s Library Learning Comms

- Academic Integrity at Fanshawe College: A Guide for Fanshawe College Students (eBook)

You would probably be hotly pursuing expulsion if you became a serial plagiarist who knows that it’s wrong and that you’ll get caught but do it anyway. The internet, and in particular, the rise of Artificial Intelligence tools (AI), such as ChatGPT and the like, may make cheating easier by offering easy access to coveted material and generative responses, but it also makes detection easier in the same way.

Students who think they’re too clever to get caught plagiarizing may not realize that plagiarism in anything they submit electronically is easily exposed by sophisticated plagiarism-detection software and other techniques. Most instructors use apps like Turnitin (built into the BrightSpace LMS, also known as FanshaweOnline at Fanshawe College ) that produce originality reports showing the percentage of assignment content copied from sources found either on the public internet, in a global database of student-submitted assignments, or through the use of Ai tools. That way, assignments borrowed, generated through AA without Prior permission from the instructor, or bought from someone who’s submitted the same or similar will also be flagged. For instance, the software would alert the instructor of common plagiarism scenarios, such as when:

- Two students in the same class submit substantially the same assignment work because:

- One of them started working on it the night before it was due and got their classmate friend to send them their assignment draft, which the cheating student changed slightly to make it look different; it will still be 90% the same, which is enough for the instructor to give both a zero and require that they meet after class to discuss who did what. Remember that supplying someone with materials for the purpose of plagiarism is also a punishable offense.

- They worked on the assignment together, even though it was designated an individual assignment only, but each changed a few details here and there at the end to make the submissions look different.

- A student submits an assignment that was previously submitted by another student in another class at the same time or in the past, at a different school, or even on the other side of the planet (either way, they’re all in the global database).

Other techniques allow instructors to track down uncited media just as professional photographers or stock photography vendors like Getty Images use digital watermarks or reverse image searches to find unpermitted uses of their copyrighted material. There are also reverse AI detection tools available for instructors to use in the same way a student would use them to generate assignments.

Plagiarism is also easy to sniff out in hardcopy assignments by any but the most novice and gullible instructors. Dramatic, isolated improvements in a student’s quality of work, either between assignments or within an assignment, will trigger an instructor’s suspicions. If a student’s writing on an assignment is mostly terrible with multiple writing errors in each sentence, but then is suddenly perfect and professional-looking in one sentence only without quotation marks or a citation, the instructor just runs a Google search on that sentence to find where exactly it was copied from.

A cheater’s last resort to try to make plagiarism untraceable is to pay someone to do a customized assignment for them, but this still arouses suspicions for the same reasons as above. The student who goes from submitting poor work to perfect work becomes a “person of interest” target to their instructor in all that they do after that. The hack also becomes expensive not only for that assignment but also for all the instances when the cheater will have to pay someone to do the work that they should have just learned to do themselves. For all these reasons, it’s better just to learn what you’re supposed to by doing assignments yourself and showing academic integrity by crediting sources properly when doing research.

But do you need to cite absolutely everything you research? Not necessarily. Good judgment is required to know what information can be left uncited without penalty. If you look up facts that are common knowledge (perhaps just not common to you yet, since you had to look them up), such as that the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. MacDonald, represented the riding of Victoria for his second term as PM even without setting foot there, you wouldn’t need to cite them because any credible source you consulted would say the same. Such citations end up looking like attempts to pad an assignment with research.

Certainly, anything quoted directly from a source (because the wording is important) must be cited, as well as anyone’s original ideas, opinions, or theories that you paraphrase or summarize (i.e., indirectly quote) from a book, article, or webpage with an identifiable author, argument, and/or primary research producing new facts. You must also cite any media such as photos, videos, drawings/paintings, graphics, graphs, etc. If you are ever unsure about whether something should be cited, you can always ask your librarian or, better yet, your instructor since they’ll ultimately assess your work for academic integrity. Even the mere act of asking assures them that you care about academic integrity. For more on plagiarism, you can also visit plagiarism.org and the Purdue OWL Avoiding Plagiarism series of modules (Elder, Pflugfelder, & Angeli, 2010).

![]() Note: If you’re enrolled in a communications course for your program that’s offered by the School of Language and Liberal Studies, the required method of citation is APA format (unless otherwise specified by your course instructor).

Note: If you’re enrolled in a communications course for your program that’s offered by the School of Language and Liberal Studies, the required method of citation is APA format (unless otherwise specified by your course instructor).

Citing and Referencing Sources in APA Style

3.5.2: Citing and Referencing Sources in APA Style

As mentioned above, a documentation system comes in two parts, the first of which briefly notes a few details about the source (author, year, and location) in parentheses immediately after you use the source, and this citation points the reader to more reference details (title and publication information) in a full bibliographical entry at the end of your document. Let’s now focus on these in-text citations (“in-text” because the citation is placed at the point of use in your sentence rather than footnoted or referenced at the end) in the different documentation styles—APA, MLA, and IEEE—used by different disciplines across the college.

The American Psychological Association’s documentation style is preferred by the social sciences and general disciplines such as business because it strips the essential elements of a citation down to a few pieces of information that briefly identify the source and cue the reader to further details in the References list at the back. The basic structure of the parenthetical in-text citation is as follows:

- Signal phrase, direct or indirect quotation (Smith, 2018, p. 66).

Its placement tells the reader that everything between the signal phrase and citation is either or direct or indirect quotation of the source, and everything after (until the next signal phrase) is your own writing and ideas. As you can see above, the three pieces of information in the citation are author, year, and location. Follow the conventions for each discussed below:

- Author(s) last name(s)

- The author’s last name (surname) and the year of publication (in that order) can appear either in the signal phrase or citation, but not in both. Table 3.5.2 below shows both options (e.g., Examples 1 and 3 versus 2 and 4, etc.).

- When two authors are credited with writing a source, their surnames are separated by “and” in the signal phrase and an ampersand (&) in the parenthetical citation (see Examples 3-4 in Table 3.5.2 below).

- When 3-5 authors are credited, a comma follows each surname (except the last in the signal phrase) and citation, and the above and/& rule applies between the second-to-last (penultimate) and last surname.

- When a three-, four-, or five-author source is used again following the first use (i.e., the second, third, fourth time, etc.), “et al.” (abbreviating et alium in Latin, meaning “and the rest”) replaces all but the first author surname.

- See Examples 5-6 in Table 3.5.2 below.

- If two or more authors of the same work have the same surname, add first/middle initials in the citation as given in the References at the back.

- If no author name is given, either use the organization or company name (corporate author) or, if that’s not an option, the title of the work in quotation marks.

- If the organization is commonly referred to by an abbreviation (e.g., “CIHR” for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research), spell out the full name in the signal phrase and put the abbreviation in the parenthetical citation the first time you use it, or spell out the full name in the citation and add the abbreviation in brackets before the year of publication that first time, then use the abbreviation for all subsequent uses of the same source. See Examples 9-10 in Table 3.5.2 below).

- If no author of any kind is available, the citation—e.g., (“APA Style,” 2008)—and the bibliographical entry at the back would move the title “APA style” (ending with a period and not in quotation marks) into the author position with “(2008)” following rather than preceding it.

- If the source you’re using quotes another source, try to find that other, original source yourself and use it instead. If it’s important to show both, you can indicate the original source in the signal phrase and the source you accessed it through in the citation, as in:

- Though kinematics is now as secular as science can possibly be, in its 1687 Pincipia Mathematica origins Sir Isaac Newton theorized that gravity was willed by God (as cited in Whaley, 1977, p. 64).

- Year of Publication

- The publication year follows the author surname either in parentheses on its own if in the signal phrase (see the odd-numbered Examples in Table 3.5.2 below) or follows a comma if both are in the citation instead (even-numbered Examples).

- If the full reference also indicates a month and date following the year of publication (e.g., for news articles, blogs, etc.), the citation still shows just the year.

- If you cite two or more works by the same author published in the same year, follow the year with lowercase letters (e.g., 2018a, 2018b, 2018c) in the order that they appear alphabetically by title (which follows the author and year) in both the in-text citations and full bibliographical entries in the References at the back.

- Location of the direct or indirect quotation within the work used

- Include the location if your direct or indirect quotation comes from a precise location within a larger work because it will save the reader time knowing that a quotation from a 300-page book is on page 244, for instance, if they want to look it up themselves.

- Don’t include the location if you’ve summarized the source in its entirety or referred to it only in passing, perhaps in support of a minor point, so that readers can find the source if they want to read further.

- For source text organized with page numbers, use “p.” to abbreviate “page” or “pp.” to abbreviate “pages.” For instance, “p. 56,” indicates that the direct or indirect quotation came from page 56 of the source text, “pp. 192-194” that it came from pages 192 through 194, inclusive, and “pp. 192, 194” from pages 192 and 194 (but not 193).

- For sources that have no pagination, such as webpages, use paragraph numbers (whether the paragraphs are numbered by the source text or not) preceded by the paragraph symbol “¶” (called a pilcrow) or the abbreviation “para.” if the pilcrow isn’t available (see Examples 1-2 and 5-6 in the table below).

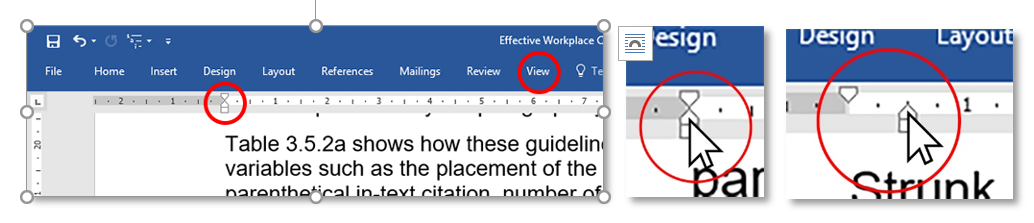

Table 3.5.2 shows how these guidelines play out in sample citations with variables such as the placement of the author and year in either the signal phrase or parenthetical in-text citation, number of authors, and source types. Notice that, for punctuation:

- Parentheses ( ) are used for citations, not brackets [ ]. The second one, “),” is called the closing parenthesis.

- The sentence-ending period follows the citations, so if the original source text of a quotation ended with a period, you would move it to the right of the citation’s closing parenthesis.

- If the quoted text ended with a question mark (?) or exclamation mark (!), the mark stays within the quotation marks (i.e., to the left of the closing quotation marks) and a period is still added to end the sentence; if you want to end your sentence and quotation with a period or exclamation mark, it would simply replace the period to the right of the closing parenthesis (see Example 8 in the table below).

Table 3.5.2: Example APA-style In-text Citations with Variations in Number of Authors and Source Types

| Ex. | Signal Phrase | In-text Citation | Example Sentences Citing Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Single author + year | Paragraph location on a webpage | According to CEO Kyle Wiens (2012), “Good grammar makes good business sense” (¶ 7). |

| 2. | Generalization | Single author + year + location | Smart CEOs know that “Good grammar makes good business sense” (Wiens, 2012, ¶ 7). |

| 3. | Two authors + year | Page number in a paginated book | Smart CEOs know that “Good grammar makes good business sense” (Wiens, 2012, ¶ 7). As Strunk and White (2000) put it, “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words . . . for the same reason that a . . . machine [should have] no unnecessary parts” (p. 32). |

| 4. | Book title | Two authors + year + page number | As the popular Elements of Style authors put it, “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words” (Strunk & White, 2000, p. 32). |

| 5. | Three authors + year for first and subsequent instances | Paragraph location on a webpage | Conrey, Pepper, and Brizee (2017) advise, “successful use of quotation marks is a practical defense against accidental plagiarism” (¶ 1). . . . Conrey et al. also warn, “indirect quotations still require proper citations, and you will be committing plagiarism if you fail to do so” (¶ 6). |

| 6. | Website | Three authors + year + location for first and subsequent instances | The Purdue OWL advises that “successful use of quotation marks is a practical defense against accidental plagiarism” (Conrey, Pepper, & Brizee, 2017, ¶ 1). . . . The OWL also warns, “indirect quotations still require proper citations, and you will be committing plagiarism if you fail to do so” (Conrey et al., 2017, ¶ 6). |

| 7. | More than five authors + year | Page number in an article | John Cook et al. (2016) prove that “Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that humans are causing recent global warming” (p. 1). |

| 8. | Generalization | More than four authors + year + page number | How can politicians still deny that “Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that humans are causing recent global warming” (John Cook et al., 2016, p. 1)? |

| 9. | Corporate author + year | Page number in a report | The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC, 2012) recommends that healthcare spending on mental wellness increase from 7% to 9% by 2022 (p. 13). . . . The MHCC (2012) estimates that “the total costs of mental health problems and illnesses to the Canadian economy are at least $50 billion per year” (p. 125). |

| 10. | Paraphrase instead | Corporate author + year + page number | Spending on mental wellness should increase from 7% to 9% by 2022 (The Mental Health Commission of Canada [MHCC], p. 13). . . . Current estimates are that “the total costs of mental health problems and illnesses to the Canadian economy are at least $50 billion per year” (MHCC, 2012, p. 125). |

For more on APA-style citations, see Purdue OWL’s In-Text Citations: The Basics (Paiz et al., 2017) and its follow-up page on authors.

In combination, citations and references offer a reader-friendly means of enabling readers to find and retrieve research sources themselves, as each citation points them to the full bibliographical details in the References list at the end of the document. If the documentation system were reduced to just one part where citations were filled with the bibliographical details, the reader would be constantly impeded by 2-3 lines of bibliographical details following each use of a source. By tucking the bibliographical entries away at the back, authors also enable readers to go to the References list to examine at a glance the extent to which a document is informed by credible sources as part of a due-diligence credibility check in the research process (see §3.2).

Each bibliographical entry making up the References list includes information about a source in a certain order. Consider the following bibliographical entry for a book in APA style, for instance:

Strunk, W., & White, E. B. (2000). Elements of style (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

We see here a standard sequence including the authors, year of publication, title (italicized because it’s a long work), and publication information. You can follow this closely for the punctuation and style for any book. Online sources follow much the same style, except that the publisher location and name are replaced by the web address preceded by “Retrieved from,” as in:

Wiens, K. (2012, July 20). I won’t hire people who use poor grammar. Here’s why. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo/

Note also that the title has been split into both a webpage title (the non-italicized title of the article) in sentence style and the title of the website (italicized because it’s the larger work from which the smaller one came). The easiest way to remember the rule for whether to italicize the title is to ask yourself: is the source I’m referencing the part or the whole? The whole (a book, a website, a newspaper title) is always in italics, whereas the part (a book chapter, a webpage, a newspaper article title) is not; see the third point below on Titles for more on this). A magazine article reference follows a similar sequence of information pieces, albeit replacing the publication or web information with the volume number, issue number, and page range of the article within the magazine, as in:

Dames, K. M. (2007, June). Understanding plagiarism and how it differs from copyright infringement. Computers in Libraries, 27(6), 25-27.

With these three basic source types in mind, let’s examine some of the guidelines for forming bibliographical entries with a view to variations for each part, such as the number and types of authors and titles:

- Author(s): The last name followed by a comma and the author’s first initial (and middle initial[s] if given)

- For two authors, add a comma and ampersand (&) after the first author’s initials

- For three or more authors, add a comma after each (except for the last one) and add an ampersand between the second-to-last (penultimate) and last author.

- Follow the order of author names as listed in the source. If they are in alphabetical order already, it may be because equal weight is being given to each; if not, it likely means that the first author listed did most of the work and therefore deserves first mention.

- If no personal name is given for the author, use the name of the organization (i.e., corporate author) or editor(s) (see the point on editors below).

- If no corporate author name is given, skip the author (don’t write “Anon.” or “N.A.”) and move the title into the author position with the year in parentheses following the title rather than preceding it.

- Year of publication: In parentheses, followed by a period

- If an exact calendar date is given (e.g., for a news article or blog), start with the year followed by a comma, the month (fully spelled out) and date, such as “(2017, July 25).” Some webpages will indicate the exact calendar date and time they were updated, in which case use that because you can assume that the authors checked to make sure all the content was current as of that date and time. Often, the only date given on a website will be the copyright notice at the bottom, which is the current year you’re in and common to all webpages on the site, even though the page you’re on could have been posted long before; see the technique in the point below, however, for discovering the date that the page was last updated.

- If no date is given, indicate “(n.d.),” meaning “no date.” For electronic sources, however, you can determine the date in the Google Chrome browser by typing “inurl:” and the URL of the page you want to find the date for into the Google search bar, hitting “Enter,” adding “&as_qdr=y15” to the end of the URL in the address bar of the results page, and hitting “Enter” again; the date will appear in grey below the title in the search list.

- If listing multiple sources by the same author, the placement of the years of publication means that bibliographical entries must be listed chronologically from earliest to most recent.

- If listing two or more sources by the same author in the same year (without month or date information), follow the year of publication with lowercase letters arranged alphabetically by the first letter in the title following the year of publication (e.g., 2018a, 2018b, 2018c).

- Title(s): Give the title in “sentence style”—i.e., the first letter is capitalized, but all subsequent words are lowercase except those that would be capitalized anyway (proper nouns like personal names, place names, days of the week, etc.) or those to the right of a colon dividing the main title and subtitle, and end it with a period.

- If the source is a smaller work (usually contained in a larger one), like an article in a newspaper or scholarly journal, a webpage or video on a website, a chapter in a book, a short report (less than 50 pages), a song on an album, a short film, etc., make it plain style without quotation marks, and end it with a period.

- If the source is a smaller work that is contained within a larger one, follow it with the title of the longer work capitalized as it is originally with all major words capitalized (i.e., don’t make the larger work sentence style), italicized, and ending with a period.

- If the source is a longer work like a book, website, magazine, journal, film, album, or long report (more than 50 pages), italicize it. If it doesn’t follow the title of a shorter work that it contains, make it sentence-style (see the Elements of Style example above, which becomes “Elements of style”).

- If the book is a later edition, add the edition number in parentheses and plain style following the title (again, see the Elements of Style example above).

- Editor(s): If a book identifies an editor or editors, include them between the title and publication information with their first-name initial (and middle initial if given) and last name (in that order), “(Ed.)” for a single editor or “(Eds.)” for multiple editors (separated by an ampersand if there are only two and commas plus an ampersand if there are three or more), followed by a period.

- If the book is a collection of materials, put the editor(s) in the author position with their last name(s) first, followed by “(Ed.)” or “(Eds.),” a period, then the year of publication, etc.

- Publication information: The city in which the publisher is based, followed by a colon, the name of the publisher, and a period.

- If the city is a common one such as New York City or Toronto, just put “New York” or “Toronto,” but if it’s an uncommon one like Nanaimo, follow it with a comma, provincial or state abbreviation, and then the colon (e.g., Nanaimo, BC: ) and publisher name.

- Keep the publisher name to the bare essentials; delete corporate designations like “Inc.” or “Ltd.”

- Web information: If the source is entirely online, replace the publisher location and name with “Retrieved from” and the web address (URL).

- If the online source is likely to change over time, add the date you viewed it in “Month DD, YYYY,” style after “Retrieved” so that a future reader who follows the web address to the source and finds something different from what you quoted understands that what you quoted has been altered since you viewed it.

- If the source is a print edition (book, magazine article, journal article, etc.) that also has an online version, give the publication information as you would for the print source and follow it with the online retrieval information.

- If all you’re doing is mentioning a website in your text, you can just give the root URL (e.g., APAStyle.org without the “http://www” prefix) in your text rather than cite and reference it.

- Magazine/Journal volume/issue information: If the source is a magazine or journal article, replace the publisher information with the volume number, issue number, and page range.

- Follow the italicized journal title with a comma, the volume number in italics, the issue number in non-italicized parentheses (with no space between the volume number and the opening parenthesis), a comma, the page range with a hyphen between the article’s first and last page numbers, and a period.

- The Dames article given as an example above, for instance, spans pages 25-27 of the June issue (i.e., #6) of the monthly journal Computers in Libraries’ 27th volume.

- Other source types: If you often encounter other source types such as government publications, brochures, presentations, etc., getting a copy of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2009) might be worth your while. If you’re a more casual researcher, you can consult plenty of online tutorials for help with APA style, such as:

- Learning APA Style and link to the free flash slideshow “The Basics of APA Style: Tutorial” (APA, 2018)

- Reference List: Basic Rules (Paiz et al., 2017) and the pages following

Though reference generator applications are available online (simply Google-search for them) and as features within word processing applications like Microsoft Word to construct citations and references for you, putting them together on your own may save time if you’re adept at APA. The following guidelines help you organize and format your References page(s) according to APA convention when doing it manually:

- Title: References

- Center the title at the top of the page at the end of your document (though you may include appendices after it if you have a long report).

- The title is not “Works Cited” (as in MLA) nor “Bibliography”; a bibliography is a list of sources not tied to another document, such as the annotated bibliography discussed in §3.3.

- Listing order: Alphabetically (unnumbered) by first author surname

- If a corporate author (company name or institution) is used instead of a personal name and it starts with “The,” alphabetize by the next word in the title (i.e., include “The” in the author position, but disregard it when alphabetizing).

- If neither a personal nor corporate author is identified, alphabetize by the first letter in the source title moved into the author position.

- Spacing: Single space within each bibliographical entry, double between them

- “Double between” here means adding a blank line between each bibliographical entry, as seen in the References section at the end of each section in this textbook.

- You may see some institutions, publishers, and employers vary this with all bibliographical entries being double spaced; just follow whatever style guide pertains to your situation and ask whoever’s assessing your work if unsure.

- Hanging indentation: The left edge of the first line of each bibliographical entry is flush to the left margin, and each subsequent line of the same reference is tabbed in by a half centimeter or so.

- To do this:

- Highlight all bibliographical entries (click and drag your cursor from the top left to the bottom right of your list)

- Make the ruler visible in your word processor (e.g., in MS Word, go to the View menu and check the “Ruler” box).

- Move the bottom triangle of the tab half a centimeter to the right; this requires surgically pinpointing the cursor tip on the bottom triangle (in the left tab that looks like an hourglass with the top triangle’s apex pointing down, a bottom triangle with the apex pointing up, and a rectangular base below that) and dragging it to the right so that it detaches from the top triangle and base.

- To do this:

Examine the bibliographical entries below for examples of the variations discussed throughout.

References

American Psychological Association (APA). (2018). The Basics of APA style: Tutorial. Learning APA Style. Retrieved from http://www.apastyle.org/learn/index.aspx

APA. (2009). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Conrey, S. M., Pepper, M., & Brizee, A. (2017, July 25). How to use quotation marks. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/01/

Cook, J., et al. (2016, April 13). Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters 11, 1-7. Retrieved from http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002/pdf

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2012). Changing directions, changing lives: The mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary: MHCC. Retrieved from http://strategy.mentalhealthcommission.ca/pdf/strategy-images-en.pdf

Paiz, J. M., Angeli, E., Wagner, J., Lawrick, E., Moore, K., Anderson, M., Soderlund, L., Brizee, A., & Keck, R. (2017, September 11). In-text citation: The basics. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/02/

Paiz, J. M., Angeli, E., Wagner, J., Lawrick, E., Moore, K., Anderson, M., Soderlund, L., Brizee, A., & Keck, R. (2017, October 2). Reference list: Basic rules. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/05/

Strunk, W., & White, E. B. (2000). Elements of style (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Retrieved from http://www.jlakes.org/ch/web/The-elements-of-style.pdf

Wiens, K. (2012, July 20). I won’t hire people who use poor grammar. Here’s why. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo/

Citing and Referencing Sources in MLA Style

3.5.3: Citing and Referencing Sources in MLA Style

The Modern Languages Association (MLA) documentation style is favoured by humanities disciplines and is, therefore, rarely used in the vocational college system. Though both two-part systems apply many of the same principles in citing and referencing, MLA favours an even more streamlined structure of citation, reduced to just the author(s) and location with no comma between:

- Signal phrase, direct or indirect quotation (Smith 66).

Notice also how the “p.” we saw in APA is assumed (omitted) in MLA. Like APA, if the author is identified in the signal phrase, the contents of the parenthetical in-text citation are reduced to just the page number—e.g., “(66)” in the example above. Slight deviations from APA style also include using “and” instead of “&” to separate two authors in MLA in-text citations, and “et al.” replaces the second, third, and any other authors, even the first time it appears if the source has three or more authors. For more on MLA-style citations, see MLA In-Text Citations: The Basics (Russell et al., 2017).

MLA bibliographical entries are similar to APA references in many respects but different in certain details. Consider typical book, article, and online article bibliographical entries in an MLA-style Works Cited list:

Dames, K. Matthew. “Understanding Plagiarism and How It Differs from Copyright Infringement.” Computers in Libraries, vol. 27, no. 6, 2007, pp. 25-27.

Strunk, William, and E. B. White. Elements of Style. 1959. 4th ed., Allyn & Bacon, 2000.

Wiens, Kyle. “I Won’t Hire People Who Use Poor Grammar. Here’s Why.” Harvard Business Review, 20 July 2012, blogs.hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo/. Accessed 20 November 2017.

The following points cover the major differences between MLA and APA:

- The title of the list of bibliographical entries is “Works Cited” rather than “References,” but it is likewise centered as the top of the page.

- All bibliographical entries are double-spaced if the document text is double spaced with no additional space between entries, but single-spaced if the rest of the document is single-spaced.

- Authors’ first names are fully spelled out rather than given as initials, and additional authors after the first in a multi-author source are given in the normal order of first name, then last name.

- Two-author sources use “and” between them (not “&”), as well as between the penultimate and last author in sources with three or more authors.

- Titles are capitalized normally (not converted into sentence style), with prepositions, conjunctions, and articles all lowercase unless they’re the first word in the title or subtitle.

- The titles of short works are surrounded by quotation marks; longer works are italicized, just as in APA style.

- The year of publication comes at the end of a book reference following the publisher name and a comma.

- If the book is republished, the original publication year appears following the title’s period and ends with a period itself.

- The edition precedes the publisher name and is separated from the latter by a comma.

- The “http://” is omitted from URLs.

For more on MLA Works Cited conventions, see MLA Works Cited Page: Basic Format (Russel et al., 2017) and the pages following it

Citing and Referencing Sources in IEEE Style

3.5.4: Citing and Referencing Sources in IEEE Style

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) documentation style is favoured by pure STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) disciplines and is therefore second to APA in its prevalence in the College of Applied Arts and Technology system. Like APA and MLA, it features a two-part system of in-text citations used throughout and references tucked away at the end of a document, but streamlines the former even further to just a bracketed number. Citations are numbered in order of their appearance, as are the bibliographical entries at the back since they correspond to the bracketed numbers throughout the document. The first few sources used would be cited as such:

Direct or indirect quotation from the first source [1]. Direct or indirect quotation from a second source [2]. Direct or indirect quotation from the first source again [1]. Direction or indirect quotation from a third source [3].

Besides being citations, the bracketed numbers may also be used as substitutes for naming the source itself, as in the following signal phrase preceding a summary of several sources:

According to [12], [15], and [17]-[20], . . . .

Bracketing the whole group of references (rather than each individually) is also acceptable (Murdoch University Library, 2018):

According to [12, 15, and 17-20], . . . .

Page or paragraph references can also be inserted into the citations as they were in APA and MLA—e.g., [12, p. 4], [15, ¶ 7].

The list of bibliographical entries at the back of the document is called “References” like in APA, but its organization differs. Rather than list the entries alphabetically by author last name, IEEE lists them in order of their appearance throughout your text with a column of the bracketed citation numbers flush to the left margin. Consider the three sample sources used to compare and contrast bibliographical entries for APA and MLA style above, now in IEEE:

[1] W. Strunk and E. B. White, Elements of Style, 4th ed., Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2000.

[2] K. Wiens. (2012, July 20). I won’t hire people who use poor grammar. Here’s why. Harv. Bus. Rev. [Online]. Available: https://hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo. [Accessed: January 27, 2018].

[3] K. M. Dames, “Understanding plagiarism and how it differs from copyright infringement,” Comp. in Libr., vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 25-27, Jun., 2006.

The basic differences between IEEE-style References, APA, and MLA are as follows:

- The section title is “References” (like APA, but unlike MLA) left-aligned (unlike both) at the top of the page.

- Bibliographical entries are listed in their order of appearance with a column of bracketed numbers flush to the left margin (unlike both APA and MLA).

- Authors’ first names are given as initials (like APA, unlike MLA) but placed before the last name (unlike both APA and MLA).

- Double authors are separated by “and” (like MLA), not “&” (APA).

- Long works are italicized (like APA and MLA), short works are in sentence style (like APA, unlike MLA), in plain style (like APA and MLA), and are in quotation marks for print-based periodicals (like MLA, unlike APA), but are not in quotation marks for strictly online articles (like APA, unlike MLA) according to the IEEE Editorial Style Manual (n.d.), but they are according to other style guides (Murdoch University Library, 2018), so this can be optional.

- Year/date of publication appears at the end for print sources (like MLA, unlike APA) but following the author for online sources (like APA, unlike MLA).

- Punctuation between parts is mostly commas for print sources (unlike both APA and MLA) and periods for online (like both APA and MLA).

When writing a document involving research in IEEE style, you are strongly advised to use a citation and references generator such as that available in MS Word. Begin one even when starting a project with notes by going to the “References” menu at the top and selecting “Insert Citation.” Though the IEEE numbering system is reader friendly, documenting research manually, especially for larger projects with several sources, is difficult because adding references out of order during the writing process requires re-numbering all subsequent citations as well as their corresponding bibliographical entry numbers at the back. Say you’re writing a 20-page report and realize that you need to add an extra source between [12] and [13], and you’ve already cited 26 sources; after inserting the new [13], you would have to manually change the old [13] to [14], [14] to [15], and 11 others both throughout your report and in your references at the back; if you added yet another source in the middle somewhere, you’ll be re-numbering them all over again. A reference generator will re-number your references with the press of a button when adding citations out of order, as well as format your References list for you. Some stylistic adjustments will be necessary, however, due to differences between MS Word’s References formatting and that modeled in the IEEE Editorial Style Manual (n.d.).

Citing Images and Other Media

3.5.5: Citing Images and Other Media

We’ve so far covered citations and references when using text, but what about other media? How do you cite an image or a video embedded in a presentation, for instance? A common mistake among students is to just grab whatever photos or illustrations they find in a Google image search, toss them into a presentation PowerPoint or other document, and be done with it. That would be classic plagiarism, however, since putting their name on an assignment that includes the uncredited work of others dishonestly presents other people’s work as their own. To avoid plagiarism, the student would first have to determine if they’re permitted to use the image and then cite it properly.

Whether you’ve been granted permission, own the image yourself, or not, you must still credit the source of the image, just like when you quote directly or indirectly. Not citing an image, even in the case of owning it yourself, will result in the reader thinking that you may have stolen it from the internet. Just because a photo or graphic is on the internet doesn’t mean that it’s for the taking; any image is automatically copyrighted by the owner as soon as they produce it (e.g., you own the copyright to all the photos you take on your smartphone). Whether or not you can download and use images from the internet depends on both its copyright status and your purpose for using it. According to Canadian legislation, using images for educational purposes is considered “Fair Dealing” (i.e., safe) when you won’t make any money on it (Copyright Act, 1985, §29), but contacting the owner and asking permission is still the safest course of action. The next safest is to ask your librarian if your use of an image in whatever circumstances might be considered offside or fair.

Standard practice in citing images in APA style is to refer to them in your text and then properly label them with figure numbers, captions, and copyright details. Referring to them in your text, referencing the figure numbers in parentheses, and placing the image as close as possible to that reference ensures that the image is relevant to your topic rather than a frivolous attempt to pad your research document with non-text space-filler. The image must be:

- Centred on the page and appropriately sized given its resolution (do not make low-resolution, pixelated images large), dimensions, and relative importance

- Labeled immediately below with a figure number given in a consecutive order along with other images in your document

- Described briefly with a caption that also serves as the image’s title

- Attributed with original title, ownership, and retrieval information, including the URL if found online, as well as copyright status information, such as “Copyright 2007 by Larissa Sayer. Printed with permission” (Thompson, 2017).

Even if you retrieve the image from public domain archives such as the Wikimedia Commons (see Figure 1), you must indicate that status along with the other information outlined above and illustrated below.

If your document is a PowerPoint or other type of presentation, however, which doesn’t give you much room for 2-4 lines of citation information without compromising clarity by minimizing its size, a more concise citation more like that you would do for directly or indirectly quoted text might be more appropriate. The citation below an image on a PowerPoint slide could thus look more like:

In either case, the References at the end of the paper or slide deck would have a proper APA-style bibliographical entry in the following format:

Creator’s last name, first initial. (Role of creator). (Year of creation). Title of image or description of image. [Type of work]. Retrieved from URL/database

If the identity of the creator is not available and year of creation unknown, as in the above case, the title moves into the creator/owner’s position and the date given is when the image was posted online:

Algonquines. (2008, August 19). [Digital Image]. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algonquin_people#/media/File:Algonquins.jpg

A common mistake is to identify “Google Images” as the source, but it’s a search engine, not a source, and doesn’t guarantee that the reader will be able to find the source you used. By having either that actual owner/author or title in the citation and the matching owner/author as the first word in the References section, you make it easy for the reader to go directly to the source you used, which is the whole point of the two-part citation/reference system.

For more, see the Simon Fraser University Library website’s guide Finding and using online images (Thompson, 2017) for a collection of excellent databases and other websites to locate images, detailed instructions for how to cite images in APA and MLA style, and information on handling copyrighted material. Though the IEEE Editorial Style Manual omits a section on citing images, the University of Manitoba’s Citation Guide – IEEE Style shows that the label below the image looks puts the figure number in uppercase along with the title caption, and replaces everything else with just the bracketed in-text citation number:

In the References at the back, the IEEE figure would appear as:

[4] “Algonquines” [Online]. (2008, August 19). Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algonquin_people#/media/File:Algonquins.jpg. [Accessed: January 27, 2018].

For more on citing images in IEEE, as well as further examples of all other source types, see Citation Guide – IEEE Style (Godavari, 2008).

For citing and referencing an online video such as from YouTube, you would just follow the latest guidelines from the official authority on each style such as APAStyle.org. Citing these is a little tricky because YouTube users often post content they don’t own the copyright to. If that’s the case, you would indicate the actual author or owner in the author position as you would for anything else, but follow it with the user’s screen name in brackets. If the author and the screen name are the same, you would just go with the screen name in the author position. For a video on how to do this exactly, for instance, you would cite the screen given under the video in YouTube as the author, followed by just the year (not the full date) indicated below the screen name following “Published on” (James B. Duke, 2017). In the References section, “[Video file]” follows the video’s italicized, sentence-style title, and the bibliographical reference otherwise looks like any other online source:

James B. Duke. (2017, January 13). How to cite Youtube videos in APA format [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydJ7k1ix-p8

Whenever in doubt about what style to follow, especially as technology changes, always consult the relevant authority on whatever source medium you need to cite and reference. If you doubt the James B. Duke Memorial Library employee’s video above, for instance, you can verify the information at APAStyle.org and see that it indeed is accurate advice (McAdoo, 2011).

Key Takeaway

Cite and reference each source you use in a research document following the documentation style conventions adopted by your field of study, whether APA, MLA, or IEEE.

Exercise

Drawing from your quotation, paraphrase, and summary exercises at the end of §3.4, assemble of combination of each, as well as media such as a photograph and a YouTube video, into a short research report on your chosen topic with in-text citations and bibliographical entries in the documentation style (APA, MLA, or IEEE) adopted by your field of study.

Parts of this chapter section have been adapted from the following:

“1.4,” 2.1”, and “3.1” in Academic Integrity at Fanshawe College Copyright © 2022 by the Academic Integrity Office at Fanshawe College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.