What to Do About Assessment?

Inner Feedback…With ChatGPT’s Help

We began this section by criticizing a generic assignment that might try to leverage ChatGPT by having students “critique” or correct an AI-generated passage (code, paragraph, outline, etc.). We were concerned that not only would this type of assessment likely be a mismatch for most disciplines, but it could create unfair advantages among students, and would almost certainly cause more grading work for the instructor. However, David Nicol, a professor in the Adam Smith Business School at the University of Glasgow, presents a guide to “turning active learning into active feedback” by encouraging students’ inner feedback (Nicol, 2022) that addresses many of these concerns.

Nicol’s Original Design

The inner feedback model for assessing students predates ChatGPT and other LLM chatbots and was designed without conceiving of them at all; it was simply an excellent way of assessing student learning. More recently, however, Nicol has recognized ChatGPT as a useful complement to the activity and has adapted his model to include it.

We first must understand the process and benefits of Nicol’s inner feedback generation model before introducing how to leverage ChatGPT with this type of assessment. (Note: We go into quite a bit of detail about this approach; Nicol’s four-page ACTIVE FEEDBACK Toolkit is the best source and should be referenced directly, although we do reproduce a number of the important parts below.)

In his guide, Nicol recognizes that educators talk about “feedback” all the time, but it is almost exclusively with respect to the comments that instructors (and sometimes peers) put on drafts or summative assessments.

Yet comments do not constitute feedback until students process them, compare their interpretation of them against their work or performance, and generate new knowledge and understanding out of that comparison. (p. 1, Nicol, 2022)

Instructors often complain about sending comments “into the void,” spending hours writing or typing detailed comments on student assignments that end up not being read, and it is all but assured that “feedback” on final assessments seldom gets integrated into the student’s learning, which then feeds back nothing at all. Even comments on draft versions of assignments may not be as effective as hoped, depending on the student’s ability—and willingness—to process and integrate the comments. Contrary to the perception that students must wait for comments before proceeding with their learning, in fact, students are generating inner feedback all the time, by “comparing their thinking, actions, and work against external information in different kinds of resources,” (p. 1, Nicol, 2022) including rubrics, textbooks, journal articles, diagrams, and even observations of activities and others’ behaviour (Nicol, 2021).

“Inner feedback is the new knowledge that students generate when they compare their current knowledge against some external reference information, guided by their goals.”

He asserts that this natural feedback loop is generally ignored in education, with deference being given to instructor-generated comments. This not only increases the instructor workload, but also discourages students from developing their own agency and skills in inner feedback. To operationalize inner feedback, students have to make “mindful comparisons of their own work against external information and make the outputs of those comparisons explicit” (p. 2, Nicol, 2022), and they must be taught how to do that.

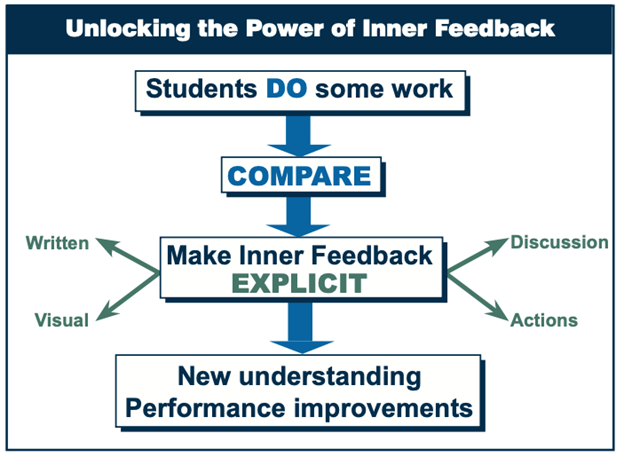

Unlocking the Power of Inner Feedback

Nicol’s research shows that by going through this process, not only do students generate their own feedback, but their observations are more varied and detailed than comments given by instructors (Nicol & Selvaretnam, 2022).

Implementing this type of assessment is quite straight-forward, even formulaic. Instructors must:

- Decide what students will do, i.e., devise the learning task that will serve as the focus for feedback comparisons (Table 1: column 1)

- Select or create appropriate comparators (column 2)

- Formulate instructions to give a focus for the comparison and to make the outputs explicit (column 3)

- Decide on next step: how to amplify the feedback students generate from resources (column 4). (Nicol, 2022)

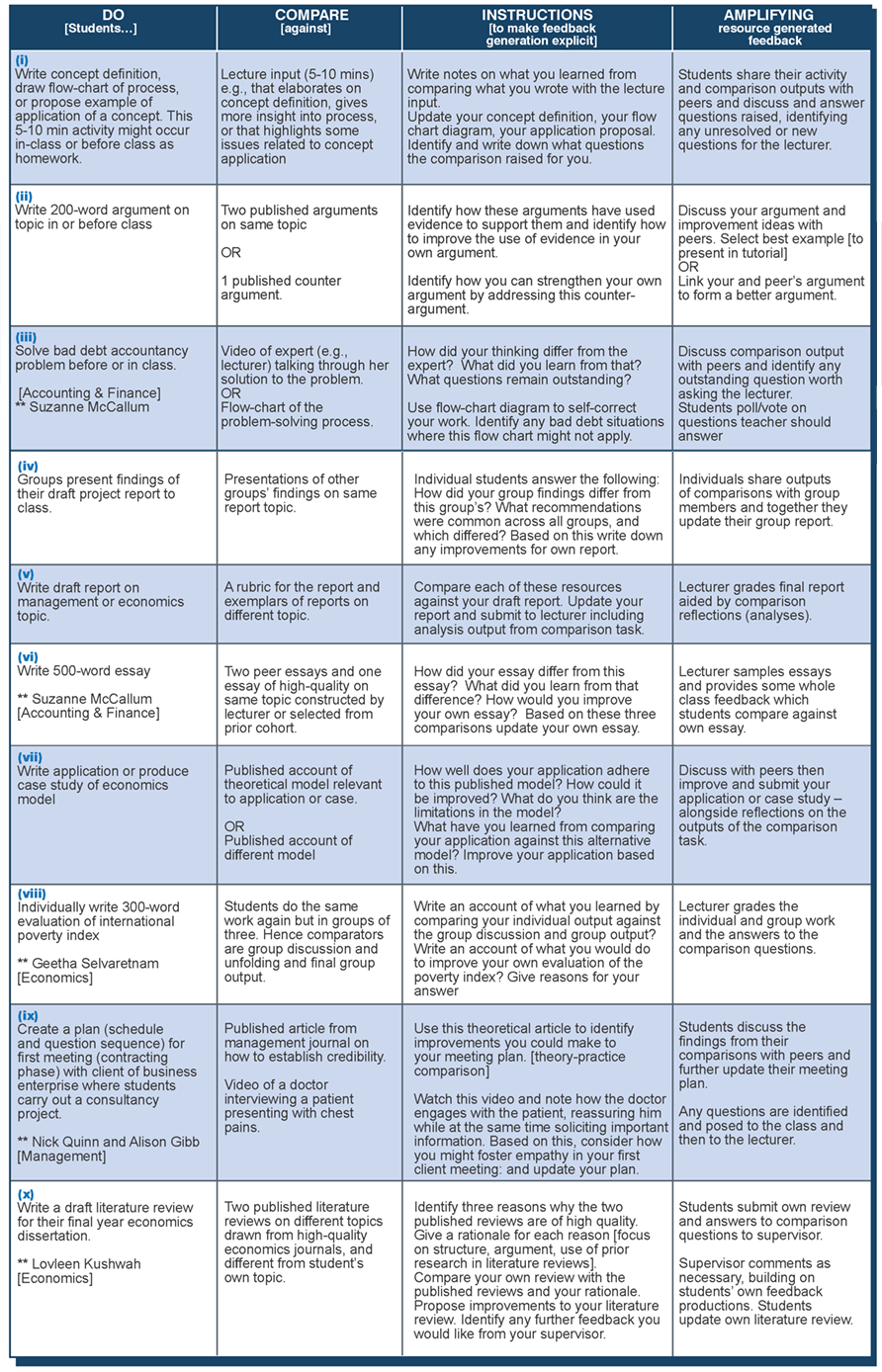

Implementations of active feedback in the Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow

It is important to identify and describe all four parts of this process. Students need to:

- know what they will do/produce;

- have access to appropriate comparators;

- understand explicitly how to generate their own feedback; and

- know how their new understanding will be instantiated/amplified.

Now here is where ChatGPT comes in: usually, the instructor provides exemplars in Step 2 as the comparators. The exemplars are published articles, instructor lectures, expert videos, rubrics, etc.; they are instructor-vetted material of high quality both in substance and format. This is the item against which the students compare their work in order to generate the inner feedback.

Nicol proposes adding a ChatGPT comparator to the mix. All of the other steps remain the same, but instead of having students only compare their work to the vetted, authoritative resources, students also generate an essay (or proposal, definition, problem, plan, report, or whatever the deliverable is) on the topic using ChatGPT and compare their work to it (along with the official resource). The ChatGPT output is not used as an exemplar, but rather, is an example of something on the topic that might exist in the world (but isn’t necessarily superior). By using the same approach as outlined above to generate inner feedback, the student compares their work and ChatGPT’s work to the authoritative resource and creates feedback about both items for themselves. They learn, first-hand, about the reliability of ChatGPT, where it might fail, how it might not perform as well as they can. By using a vetted, reliable resource in conjunction with ChatGPT, they can learn how to think critically about ChatGPT, while simultaneously being shown that there are no shortcuts and that they cannot rely on ChatGPT to effectively cheat (Rose, 2023).

We began this section by stating that both oral exams and developing inner feedback are ways to increase the AI-immunity of your assessments, but they are both also very effective learning and assessment methods. Not only is the assessment effective, but the learning that takes place in preparation for the assessment is often of a higher quality (Clay, 2023; Nelson, 2010). The key is in guiding and framing these new assessment activities for students. For oral exams, it’s about setting expectations and organizing an effective, but conversational, assessment. For creating inner feedback, it’s about helping students become agents in their own learning.

Media Attributions

- Table 1: Implementations of active feedback in the Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow