Stepping Stone 3: Sport, Games, and Competition

by Mitchell Huguenin

Introduction

Whether played to instill life skills, for the purpose of fun, or in competition – Indigenous peoples have played their own sports and games since time immemorial. Such physical activities were and continue to be a uniting force in empowering Indigenous communities to come together. The contributions of Indigenous peoples to sport are numerous and still visible across Turtle Island today. Sport on the other hand has also been used by colonial powers as an instrument of assimilation. Movement and health professionals may become better equipped to work with modern Indigenous populations by developing an appreciation for these historical and culturally-relevant dynamics of sport, games, and competitions.

Wholistic Learning Objectives

Stepping Stone 3 provides learners an opportunity to become acquainted with the historical significance and modern evolution of sport, games, and competition within Indigenous cultures. Learners will also explore the role of mainstream sport within Indigenous communities and in Indian Residential schools.

Upon completion of Stepping Stone 3, learners should be able to:

*click through all 5 slides to read each of the wholistic learning objectives*

Warm-up Activity

It can be tempting to sprint ahead under the guise of reconciling. Reconciliation, however, is a process with no clear finish line and requires that one become acquainted with many important truths before moving beyond their crucial first steps.

In Stepping Stone 3, we make one final jump back in time to find the “truth”. Through this Stepping Stone, we will discuss the ways in which Indigenous peoples engaged in sport, games, and competition over the eras – during both pre- and post-contact times.

- Watch “Heritage Minute: Tom Longboat”

- The story of Tom Longboat is representative of the athletic abilities and skills utilized by Indigenous peoples long before and since colonization occurred. Keep this in mind as you navigate the various sections of Stepping Stone 3.

Sport in Pre-Contact Turtle Island

Indigenous peoples have played their own culturally relevant, place-based sports for thousands of years. The physical activities that evolved into what we recognize as traditional Indigenous sports and games had ancient links with recreation, rituals, and warfare. However, the primary purpose of sport in most contexts was to teach people practical skills necessary for daily life. Indeed, traditional sports were largely focused on maintaining, exercising, or honing the physical abilities people required for carrying out fundamental subsistence activities (e.g., hunting, fishing, harvesting, etc.). They were therefore played by both men and women, and by both the young and the old – all of whom participated in meeting community sustenance and survival needs. Examples of traditional Indigenous sports and games with utilitarian purposes (played within or between communities) include archery, spear throwing, wrestling, tug-of-war, and foot, canoe, and sled racing.

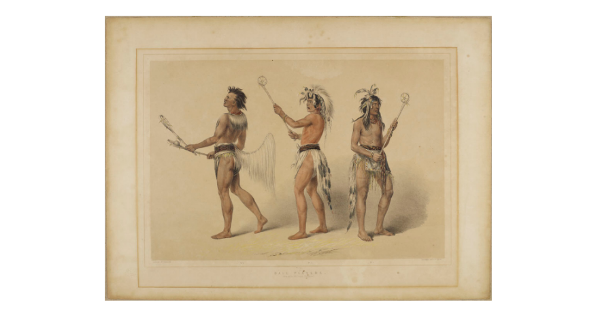

Conversely, activities such as drum dancing or lacrosse (while providing enjoyment to participants and in certain cases, entertainment to spectators) also had deep cultural significance. In particular, lacrosse held a sacred place among many Indigenous peoples of the past (and it remains a popular and celebrated sport in modern times). Often referred to as the “Creator’s Game,” lacrosse and analogous stick and ball games were known to various Indigenous peoples by numerous different names, including baggataway (Algonquian), kabocha-toli (Choctaw), tewaarathon (Mohawk), and ká:lahse (Oneida) (de Bruin & Calder, 2017). The game was played to keep men fit for both war and hunting, to strengthen diplomatic alliances, to settle diplomatic disputes, and to honour the gift of life. Oral histories tell of gruelling matches persisting for several days and involving hundreds of participants; hence, legends surrounding lacrosse grew over time and in fact, still abound today. For Indigenous people, playing lacrosse reinforced one’s unique relationship with Creation and the Creator, therefore maintaining strong cultural connotations even following the inevitable fallout of first contact. Sadly, after colonization other traditional sports would vanish from play because of factors like loss of land and community fragmentation.

Activity 1

Read “Inuit Games”

- How were/are Inuit games tied to the Inuit homelands and their traditional subsistence lifeways?

- In what ways were/are Inuit games an essential element in recreation and celebration?

- Reflect the role that Inuit games continue to play in today’s society.

Activity 2

Watch “The History of Lacrosse | Honoring the Native American Heritage”

- Explain how lacrosse is a “medicine” and can be used for healing self and community?

- Consider the message of “giving thanks” presented in this video. Be mindful of that message as you navigate the upcoming sections of this Stepping Stone.

Sport in Post-Contact Turtle Island

Indigenous sporting practices and many other physical culture activities were repressed following first contact as communities slowly came under the effective control of colonial laws and oppressive customs. By the nineteenth century, most traditional sports, games, and competitions had largely been displaced by imposed settler-colonial conceptions of leisure and recreation. This was done deliberately to bring about a fundamental shift in the values and behaviours of Indigenous people, as it was thought that participation in settler-colonial activities would contribute to their gradual assimilation into the main body politic. The intent was to breakdown cultural and traditional connections by enforcing interest in mainstream settler-colonial activities such as baseball or hockey rather than Indigenous activities such as drum-dancing or lacrosse. Although Indigenous people were forced into the mainstream sporting activities that were introduced over the course of colonization, they often used them as mechanisms for self and community empowerment. For example, “sports days” emerged as colonially accepted forms of social organization for Indigenous peoples following the passage of the Indian Act in 1876. It was hoped that these “sports days” would facilitate an understanding of settler-colonial activities as superior while positioning Indigenous activities as inferior and undesirable. However, Indigenous people leveraged “sports days” to challenge and resist colonial agendas, treating them as opportunities to gather without raising the suspicions of the assigned Indian agent (Forsyth, 2007). Indigenous people also found ways to blend settler-colonial or Euro-Canadian activities within their traditional ones. The Métis for instance developed jigging – a unique dance that combines the intricate footwork of traditional dancing with the instruments and form of Euro-Canadian music (Métis Nation of Ontario, n.d.). Despite mainstream sport being implicated in Canada’s history of assimilation, Indigenous people would ultimately reconceptualize settler-colonial ways of play and competition into meaningful opportunities that bolstered their cultural identities.

Activity 3

Read “A History of Colonial Lacrosse”

- The transformation of the “Creator’s game” into modern lacrosse began in 1636 when Jesuit missionary Jean de Brebeuf documented a Huron-Wendat contest in what is now southeastern Ontario. Consider how the ongoing appropriation of lacrosse by Euro-Canadians changed the game and its accessibility to Indigenous peoples.

Activity 4

Historic Métis seldom enjoyed significant leisure time, as their lives revolved around the heavy demands of the fur trade. Nevertheless, ancestral communities developed various sports, games, and physical culture activities which have since become synonymous with the Métis Nation.

Read “Métis jigging: a better cardio workout than aerobics or a run?”

- What are the benefits associated with research studies like professor Foulds’? Reflect on Indigenous physical culture revitalization and community health factors.

Sport and Residential Schooling

Sports were a major part of the Residential School system; a network of mandatory, government-sponsored religious boarding schools where Indigenous children were sent to be indoctrinated into Canadian society. Canada’s most aggressive attempt to erase Indigenous culture, language, and traditions was committed through this colonial and oppressive system of schooling. In these hostile environments, sport was employed once again as a tool for colonization and assimilation. Within Residential Schools, Indigenous physical culture activities were forbidden and replaced with conventional activities such as baseball, basketball, soccer, and hockey. In a 2018 article published by the University of Manitoba, director of First Nations Studies in the Faculty of Social Science at Western University, Janice Forsyth links Euro-Canadian sport to Residential School assimilation processes :

Built into it (sport) are ways of prioritizing values and beliefs that may not be part of Indigenous cultural heritage… If you shift the lens a bit, and instead see sport as a cultural activity that teaches and reinforces cultural values and beliefs, it’s not hard to see how sport has been implicated in the history of cultural transformation. In Residential Schools especially, it was used as a tool to instill dominant values and beliefs in the students who went there (University of Manitoba, 2018, paras. 6-7).

Although some Residential Schools had colonial recreation programs for detained students, these programs were usually underfunded and undersupplied. Underfunding was extremely common at Residential Schools in general, resulting in high rates of illnesses or diseases, and poor nutrition and living conditions. The negative and traumatic experiences of those who endured or survived an education within the Residential School system were documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) in its 2015 final report. The survivors’ testimonies of truth published therein suggest that participation in organized school sports offered some students a measure of respite from their dire circumstances away from family and community, and “gave them a sense of identity, accomplishment, and pride (TRC, 2015, p. 199).” In that same report, the TRC released 94 “Calls to Action” to redress the legacy of Residential Schools and to initiate the process of reconciliation in Canada. Five of the TRC’s Calls of Action relate specifically to sport in Canada:

-

- We call upon all levels of government, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, sports halls of fame, and other relevant organizations, to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.

-

- We call upon all levels of government to take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel.

-

- We call upon the federal government to amend the Physical Activity and Sport Act to support reconciliation by ensuring that policies to promote physical activity as a fundamental element of health and well-being, reduce barriers to sports participation, increase the pursuit of excellence in sport, and build capacity in the Canadian sport system, are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples.

-

- We call upon the federal government to ensure that national sports policies, programs, and initiatives are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples, including, but not limited to, establishing:

i. In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, stable funding for, and access to, community sports programs that reflect the diverse cultures and traditional sporting activities of Aboriginal peoples.

ii. An elite athlete development program for Aboriginal athletes.

iii. Programs for coaches, trainers, and sports officials that are culturally relevant for Aboriginal peoples.

iv. Anti-racism awareness and training programs.

-

- We call upon the officials and host countries of international sporting events such as the Olympics, Pan Am, and Commonwealth games to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ territorial protocols are respected, and local Indigenous communities are engaged in all aspects of planning and participating in such events (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 10)

Governments and sporting officials are currently working to address these Calls to Action as a means of reconciling with Indigenous peoples in Canada. It remains unclear how or when the TRC’s Calls to Action will be fully implemented.

Activity 5

What comes to mind and what feelings do you experience when looking at the images below? In your opinion, how might sports serve as an avenue for promoting and celebrating Indigenous culture as the country takes steps toward reconciliation?

Activity 6

Read “781: A Story of Sports and Survival in Canadian Residential School”

Content Note: This recording includes references about residential schools, structural and systematic modes of oppression, and violence against children.

Support is available for anyone affected by the ongoing impact of residential schools. If you require emotional support or assistance, the Residential School Survivors Society (IRSSS) can be contacted toll-free at 1-800-721-0066.

Activity 7

Visit Sports and reconciliation

- Using the “What’s happening?” dropdown tabs, determine what the Canadian government’s level of commitment has been thus far in fulfilling the Calls to Action related to sports and reconciliation. What progress has been made? What additional efforts still need to transpire?

Sporting and Cultural Competitions

Participation in both traditional and mainstream sports has become a way through which Indigenous peoples can celebrate their rich and diverse cultural heritages. It also provides an opportunity for Indigenous youth to exercise, engage in teamwork, relieve stress, and learn resilience when faced with challenging situations. These and other benefits of athletic competition are promoted at events like the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG)–one of the most significant sporting and cultural events for the First Peoples of Turtle Island.

While the vision to hold a competition exclusively for Indigenous athletes began to take shape as early as the 1970s, the very first NAIG event would not occur until 1990, in Edmonton, Alberta (North American Indigenous Games, n.d.). The Games have been staged intermittently since then, bringing together competitors from all over Canada, as well as from 13 regions in the United States. Gold, silver, and bronze medals were awarded in fourteen different sports categories (3-D archery, athletics, badminton, baseball, basketball, canoe/kayak, golf, lacrosse, rifle shooting, soccer, softball, swimming, volleyball, and wrestling) at the 2017 NAIG in Toronto, Ontario. The next iteration of NAIG was planned for July 2020 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq Nation. It was set to host 5,000 athletes in what would have been the largest multi-sport event ever hosted in Atlantic Canada, but the event was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of this publication, the tenth NAIG is scheduled to take place in 2023 in Halifax.

Various other athletic competitions have been developed by Indigenous peoples, including the World Indigenous Games (which involves Indigenous athletes from all over the world), the Arctic Winter Games (which brings together circumpolar peoples residing in communities from throughout the Arctic), and the NYO Games (previously known as the Native Youth Olympics). Indigenous peoples also compete at smaller scale, local community events or tournaments. The Métis for example, honour their fur trade ancestors by holding Voyageur Games, which test the bodily and mental rigor of competitors. There are also competitive pow wows where dancers – motivated by the challenge and physicality of dance – come together to contend for honours and prizes. Competing in dances like fancy dance, fancy shawl, and grass dance, as with any aerobic endeavour, requires a high level of cardiovascular fitness, agility, and athleticism. Having ties to traditional or cultural physical activity competitions also require respectful knowledge transformation from Elders or Knowledge Keepers from the community to engage, practice, and compete.

Watch “What’s a pow wow?” (1:58)

Indigenous peoples have also advocated for their sovereign communities to be represented at international competitions. This has included efforts by the Iroquois Nationals lacrosse team to participate in the Olympics under its own flag. If lacrosse becomes an Olympic medal sport (it will be considered for a return to the Olympic games in 2028), the team will need to continue fighting for their nation (the Haudenosaunee Confederacy) to be represented. According to Leo Nolan, executive director of the Iroquois Nationals: “We basically have to sell the IOC (International Olympic Committee) on our international experience, our international standing, our sovereignty, and the good things that’ll happen if we’re there playing lacrosse, the game we originated” (The Canadian Press, 2021, para. 39). The decision on whether or not the Iroquois Nationals will qualify for the 2028 Olympics is scheduled to be made in 2024.

Watch “NAIG 2023 | Pjila’si” (1:05)

Activity 8

Watch “Native Games: Origins” (1:05)

Although focusing specifically on the NYO Games, this video illustrates the many ways through which Indigenous sports and athletic competition are tied to culture and valued as a form of contemporary medicine.

- Consider how the concept of “competition” may differ when viewed through an Indigenous lens versus a non-Indigenous lens.

- In what ways can you advocate for the continuation of Indigenous sporting and cultural competitions? Are there appropriate ways that you might be able to participate and/or promote such events?

Wellness Break

Many athletes routinely use visualization techniques as part of exercise, practice, and competition.

Take a few moments to yourself to imagine the full picture of a future desired goal or outcome, perhaps one related to your purpose for exploring this resource.

Try to visualize the details and the way it feels to carry out and reach your desired objective.

Stepping Stone 3 Summary

In this Stepping Stone, we considered the cultural relevancy of traditional Indigenous sports, games, and competitions, both prior to and following first contact. We provided context for how sport was used historically by colonial powers as a tool for assimilation and oppression, and determined its function during the tragic Residential School era. You concluded your learning in Stepping Stone 3 by exploring examples of Indigenous athletic competition, whilst reflecting on the important ties to culture and celebration. Of the 94 Calls to Action published in final report of the TRC, numbers 87 to 91 are specific to sport. The TRC recognized the important role that sport plays in reconciliation, as well as the role sport continues to play in empowering and uplifting Indigenous peoples.

In this Stepping Stone, we considered the cultural relevancy of traditional Indigenous sports, games, and competitions, both prior to and following first contact. We provided context for how sport was used historically by colonial powers as a tool for assimilation and oppression, and determined its function during the tragic Residential School era. You concluded your learning in Stepping Stone 3 by exploring examples of Indigenous athletic competition, whilst reflecting on the important ties to culture and celebration. Of the 94 Calls to Action published in final report of the TRC, numbers 87 to 91 are specific to sport. The TRC recognized the important role that sport plays in reconciliation, as well as the role sport continues to play in empowering and uplifting Indigenous peoples.

Cool-down Activity

As you navigated the content in Stepping Stone 3, you were asked to keep in mind Tom Longboat’s story and what it represents. At the height of his success and fame, Longboat was asked to speak at the Residential School he was forced to attend as a child. Tom Longboat refused, by saying “I wouldn’t even send my dog to that place.”

As you navigated the content in Stepping Stone 3, you were asked to keep in mind Tom Longboat’s story and what it represents. At the height of his success and fame, Longboat was asked to speak at the Residential School he was forced to attend as a child. Tom Longboat refused, by saying “I wouldn’t even send my dog to that place.”

The truth of sport is not necessarily founded in wins and losses, but in the commitment made by athletes to overcome physical, mental emotional, or spiritual challenges.