Stepping Stone 2: Post-Contact Physical Culture

by Mitchell Huguenin

Introduction

As indicated at the beginning of Stepping Stone 1, Indigenous people have unique needs when it comes to health, well-being, and physical activity. This is in part a result of their diverse cultures and traditions as well as the impacts of colonialism and Canada’s assimilation policies. In order to address these needs and begin rebuilding relationships, we must acknowledge the many ways in which Indigenous physical culture transformed because of colonization. We must also recognize how this challenging past continues to inform many modern-day experiences in Canada.

Wholistic Learning Objectives

Stepping Stone 2 invites learners to trace the history of Indigenous physical culture following first contact with Europeans. Learners are encouraged to consider how land-based lifestyles evolved over time and were adapted as a result of colonization.

Upon completion of Stepping Stone 2, learners should be able to:

*click through all 5 slides to read each of the wholistic learning objectives*

Warm-up Activity

It can be tempting to sprint ahead under the guise of reconciling. Reconciliation, however, is a process with no clear finish line and requires one to become acquainted with many important truths before moving beyond their crucial first steps.

As we did in the previous Stepping Stone, finding “truth” requires making another leap into the past. In the context of Stepping Stone 2 however, we will be visiting a difficult chapter in Indigenous history, when Indigenous physical culture irrevocably changed following first contact.

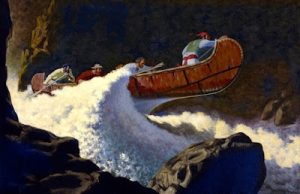

The image below is just one example of post-contact Indigenous physical culture. As you look at the image, consider the following questions:

- What does the image mean to you? Make a list of words or phrases that come to mind when looking at the image.

- Can you think of some reasons for the historical significance of the image and/or what it may represent?

- Can you make a personal connection to what is displayed in the image? What feelings and/or questions does it evoke?

Activity 1

Like other aspects of traditional life, physical culture was historically defined by the intergenerational relationships that Indigenous peoples sustained with the lands, waters, and lifeforms of their territories. For them, the arrival of European newcomers and subsequent emergence of colonial society disrupted both the natural environment and associated cultural practices in countless ways.

Watch “Four Faces of the Moon” and reflect on your own identity within the histories of colonialism in Canada.

- What privileges and disadvantages have you/your family experienced as a product of colonialism?

- Connect this personal experience to your purpose for taking this course.

“The Great Dying”

Before the arrival of European explorers, traders, missionaries, and settlers, Turtle Island was occupied by diverse and thriving Indigenous populations. However, with the 1497 expedition of John Cabot (the earliest-known European exploration of North America since the eleventh-century Norse voyages to “Vinland”), the concerted European conquest of what is now called Canada began. First contact with Europeans changed Indigenous ways of life forever; primarily, through the transmission of “Old World” diseases. Lacking biological immunities, alien afflictions including smallpox, influenza, bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, measles, and malaria had devastating effects on Indigenous health and health systems:

“In some cases, people who were sick may have otherwise survived if provided with basic care. First Nations health systems had never encountered these diseases and were unprepared to deal with them. These epidemics continued throughout the historic period and caused ongoing and dramatic population decline”. (First Nations Health Authority, n.d., para. 13)

Given their lack of familiarity with these diseases, traditional healers were powerless to respond. Left overwhelmed by waves of sickness and loss of life, it was not uncommon that physical culture practices like hunting and foraging became interrupted in some Indigenous communities. Simultaneously, over-hunting by Europeans and the introduction of invasive “Old World” plant and animal species would upset the natural balance, thus further disrupting Indigenous subsistence life. The lack of available food and nutrition intake, as a result, weakened the immune systems of those surviving – perpetuating a destructive cycle of population collapse. During this time, mortality rates in affected villages ranged from 50% to 90% (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.). Because of this, Indigenous oral histories were partially if not entirely lost. In this depopulated landscape, the concept of terra nullius (a term meaning “nobody’s land” and used to justify assertions that territories unoccupied by Christians could be acquired by Christian states) began to take root. 15th century Papal Bulls known as the Doctrine of Discovery provided a legal framework for European explorers to lay claim to Indigenous territories, ultimately giving way to colonization.

Activity 2

Read “Why have Indigenous communities been hit harder by the pandemic than the population at large?”

- What is the “virgin soil” theory and how – according to the article – is it flawed?

- Why were Indigenous people at the highest risk amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

Revered Physiques

The diseases carried by Europeans to the “New World” would be transmitted through trade, missionary work, and other contact with Indigenous peoples over the ensuing decades. And thus, as European colonization of Turtle Island unfolded, Indigenous population numbers continued to plummet. In spite of this great loss of life, the lineage of Indigenous physical culture persisted. Traditional lifeways – although progressively influenced by colonial ideologies and processes – kept people active and connected to the natural resources they relied upon for survival. This, in combination with a subsistence diet, built strong physiques; a fact that did not go unnoticed by the newcomers.

The historical accounts of early Europeans offer some perspectives on the physical fitness of Indigenous peoples, and in fact, often describe their outward appearances in quite complimentary terms. Even Samuel de Champlain – one of the foremost colonizers of Turtle island – acknowledged the striking figures of the Haudenosaunee warriors he infamously encountered in 1609:

“I saw the enemy come out of their barricades to the number of two hundred, in appearance strong, robust men.” (de Champlain & Biggar, 1922, pp. 97-98).

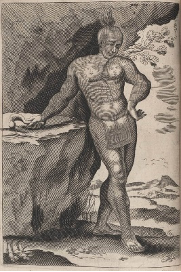

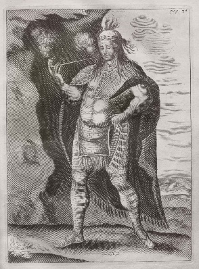

Jesuit missionaries detailed their observations about the Indigenous peoples that they encountered in reports that came to be known as the Jesuit Relations. “They are of lighter build than we are; but handsome and well-shaped,” claimed Father Pierre Biard in 1611. Father Francesco Bressani shared a similar opinion, writing in 1653: “they are strong, tall in stature, and well-proportioned: more healthy than we.” Similarly, engravings made in Jesuit priest François Du Creux’s “Historiae Canadensis seu Novae Franciae” (published in 1664) uniquely depict the artist’s admiration of Indigenous physiques:

Activity 3

Indigenous peoples were recounted as being strikingly healthy specimens in a number of the historical memoirs left by explorers and missionaries.

Reflect on the various reasons why Indigenous peoples were so frequently admired in this way by Europeans. Research and consider the differences between “Old World” (European) and “New World” (Indigenous) physical culture and lifestyle practices.

Backbone of the Fur Trade

Driven by commercial objectives, westward expansion made it increasingly difficult for Indigenous peoples to access seasonal harvesting sites, with more and more of their territories becoming claimed by colonial powers. And although forced to adapt their ways of life because of the rapidly growing and intensely competitive fur trade (an extensive trade enterprise which supplied European demand for pelts to make clothing), seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European records still emphasize the physicality of Indigenous peoples. Voyageurs for instance, who were frequently of Indigenous or mixed-Indigenous descent (e.g., Métis), are credited with accomplishing the hard manual labour of the fur trade. Those employed by companies and merchants as voyageurs engaged in the grueling work of transporting furs, often over long distances by foot and canoe. Author Washington Irving attests to their rugged endurance in his 1836 book Astoria: Or, Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains:

“Their natural good-will is probably heightened by a community of adventure and hardship in their precarious and wandering life… They are dextrous boatmen, vigorous and adroit with the oar and paddle, and will row from morning until night without a murmur.” (p. 24)

For voyageurs, transporting furs by canoe necessitated paddling at highly aerobic paces (at a rate of about 40-50 strokes per minute and portaging the canoes (and contents) between waterways (Nute, 1931). Furs were carried in 40 kg (90 lbs) bundles or “piéces.” Two of these piéces (totalling 80 kgs or 180 lbs) made an ordinary load for portaging, but as indicated by 19th century scholar Dr. Grace Lee Nute (1931), “emulation among the men in proof of unusual strength or endurance caused many an éngage (fur trade employee, i.e., voyageur) to carry three or four” (p. 24) Being a voyageur was dangerous despite their rugged credentials. Drowning was common, along with cuts, bruises, broken bones, and hernias:

“So much lifting and carrying proved a strain to all but the toughest, and many a bruised foot and wrenched ankle were the result of nearly every portage. Hernia; was very prevalent among voyageurs and not infrequently caused death.” (Nute, 1931, p. 46).

While Indigenous women were rarely employed as voyageurs, they played an integral part in the fur trade in numerous other ways. When travelling on expeditions alongside voyageurs (often to whom they were married “à la façon du pays” or “according to the custom of the country” (a marriage not formalized by Christian rite)), women produced clothing, harvested and prepared food, and at times acted as interpreters, guides, and liaisons. “They were indeed very active contributors, taking on even the most laborious duties when needed. In his 1771 journal, HBC employee and explorer Samuel Hearne remarks about such women, suggesting that “one of them can carry, or haul, as much as two men can do. They also pitch our tents, make and mend our clothing, keep us warm at night; and in fact, there is no such thing as travelling any considerable distance, or for any length of time, in this country, without their assistance” (Duhamel, 2020, para. 18).

Activity 4

Read “Canoe trek traces Métis history in Canada”

Watch “Elder Elize Hartley talks about the Metis Sash”

Reflect on the experiences shared by those voyageur-descendants who participated in the 2014 MNO Canoe Expedition.

The Métis Sash (sometimes called a “Ceinture Fléchée” or “Arrow Belt”) is an enduring symbol of Métis identity, having first been used by voyagers during the fur trade era. Consider the ways in which the Sash – given its practical uses – is an artifact of Indigenous physical culture.

Activity 5

Watch “Bonga”

Please be advised that some of the terminology expressed in this video may be used conventionally in the United States and does not necessarily reflect common language usage in Canada. In the United States, the term “Native Americans” is sometimes the preferred collective noun for Indigenous people living in that country.

- Who was George Bonga?

- What legendary physical feat was he known for?

- How was George Bonga not only able to withstand immense physical labor, but able to personally navigate multiple and dissimilar cultural worlds?

The Colonial Legacy

Indigenous peoples both adapted to and resisted the maelstrom of changes brought on by colonization. They would continue to do so throughout the fur trade and early industrial era, as settler-colonial authority expanded to facilitate land acquisition, stifling land-based customs including hunting and harvesting practices. In fact, following Canada’s confederation in 1867, laws and acts of parliament were passed prohibiting many traditional food-centred practices and forcing Indigenous peoples onto reserves, often with infertile or unworkable lands.

In 1876 the Indian Act was introduced, subsuming a number of colonial policies that sought to extinguish Indigenous lifeways, which were wrongly perceived as inferior and uncivilized. The Indian Act was then amended in 1920, mandating that Indigenous children between the ages of seven and sixteen years attend residential boarding schools. The goal of the residential school system was to remove and isolate children from the influence of their families, communities, and cultures. To “kill the Indian in the child” and assimilate them into Euro-Canadian society. Due to the abhorrent living conditions and unimaginable abuse at the residential schools (which in some cases included the deliberate malnutrition of students), sometimes the child themselves died:

“In addition to the cultural and social effects of being forcibly displaced, many children suffered physical, sexual, psychological, and/or spiritual abuse while attending the schools, which has had enduring effects including, health problems, substance abuse, mortality/suicide rates, criminal activity, and disintegration of families and communities. Moreover, many of the residential schools were severely underfunded, providing poor nutrition and living conditions for children in their care, leading to illness and death.” (Wilk et al., 2017, p. 2)

Comparably poor conditions manifested in Indigenous communities and reserves as well, which contributed to disproportionate rates of tuberculosis throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Moreover, the loss of land-based, physical culture lifeways as a result of ongoing colonialistic processes, diminished opportunities for sustained physical activity. And as the 20th century proceeded, additional health issues arose with lifestyles becoming more sedentary and diets changing to include more processed foods. It was the cumulative effects of this tumultuous post-contact history that debilitated Indigenous physical culture practices and lifeways. The consequences on modern Indigenous health and well-being, as will be discussed in greater detail in Stepping Stones 5 and 6, have been extremely severe.

Activity 6

Canada’s history of land acquisition and resource extraction altered the relationship between Indigenous peoples and their lands, all in the pursuit of advancing so-called civilization. Today, land remains the central point of conflict between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Consider what happens when that land is taken away, or, when people are taken away from it.

Activity 7

Listen to “Unreserved: The dark history of Canada’s Food Guide”

Content Note: This recording includes references about residential schools, structural and systematic modes of oppression, and violence against children.

Support is available for anyone affected by the ongoing impact of residential schools. If you require emotional support or assistance, the Residential School Survivors Society (IRSSS) can be contacted toll-free at 1-800-721-0066.

- What was the central cause of malnutrition in Indigenous communities and residential schools during the mid 20th century?

- What was the most important connection between the residential school nutrition experiments and Canada’s Food Guide?

- Reflect on the ongoing impacts of these nutritional experiments.

Activity 8

In a 2021 interview with the CBC, Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Justice Murray Sinclair, said that generations of people in Canada were raised to believe “that Indigenous people were inferior, that they were unclean, that they were pagans” (CBC Radio, 2021, para. 26). The question of whether people can change when “given an opportunity to confront their ignorance and to learn more,” remains.

Reflect on the changes that you might make, or, actions that you might take having now learned about Canada’s colonial legacy as it relates to Indigenous physical culture.

Wellness Break

Métis Voyageurs and other canoe-men of the Fur Trade sang songs that helped them to both maintain a consistent paddling rhythm and keep their spirits up during long journeys.

Listen to a song that enlivens your spirits and feel free to move about before continuing on with the Stepping Stone.

Stepping Stone 2 Summary

In Stepping Stone 2, we explored the devastation that followed first contact by colonizers. We then uncovered some of the historical opinions held by European settlers or newcomers about Indigenous physicality. The multiple ways in which colonization operated to influence physical culture (and how Indigenous peoples adapted) were also discussed. The 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report speaks to the gaps in Canada’s collective knowledge of the harms inflicted upon Indigenous peoples through colonization (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). It will take time to unlearn and relearn the full truth of what took place over the past centuries. Accept this as an initial step in the unlearning and relearning journey, and re-embrace your role in reconciliation as you make progress through subsequent Stepping Stones.

Cool-down Activity

Before beginning this Stepping Stone, you were asked to look at the image below and to consider some guiding questions.

Before beginning this Stepping Stone, you were asked to look at the image below and to consider some guiding questions.