Stepping Stone 1: Pre-Contact Physical Culture

by Mitchell Huguenin

Human movement professionals work with populations of varying ages, backgrounds, and abilities to help them achieve their fitness and wellness goals and improve quality of life. In Canada, Indigenous peoples are the fastest growing population – one that has unique needs when it comes to health and physical activity. Before these needs can be appropriately addressed, it is essential to first understand important truths about Indigenous physical culture, including how it functioned before Europeans ever saw the shores of Turtle Island.

Wholistic Learning Objectives

Stepping Stone 1 invites learners to trace the history of Indigenous physical culture prior to first contact with Europeans. Learners are encouraged to consider the multiple and often interconnected implications of active, land-based lifestyles as they existed on Turtle Island for thousands of years.

Upon completion of Stepping Stone 1, learners should be able to:

*click through all 5 slides to read each of the wholistic learning objectives*

Warm-up Activity

It can be tempting to sprint ahead under the guise of reconciling. Reconciliation, however, is a process with no clear finish line and requires that one become acquainted with many important truths before moving beyond their crucial first steps.

In the context of Stepping Stone 1, finding “truth” involves making a jump back in time, to explore the historical dynamics of Indigenous physical culture.

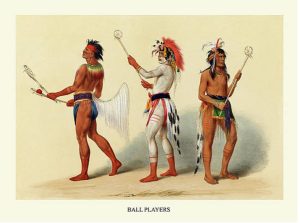

The image below is just one example of pre-contact Indigenous physical culture.

As you look at the image, consider the following questions:

- What does the image mean to you? Make a list of words or phrases that come to mind when looking at the image.

- Can you think of some reasons for the historical significance of the image and/or what it may represent?

- Can you make a personal connection to what is displayed in the image? What feelings and/or questions does it evoke?

Activity 1

Blackfoot researcher, Dr. Leroy Littlebear has said that “The land is a sacred trust from the Creator. The land is the giver of life like a mother.” Although there is much diversity between First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, a deep and abiding relationship with the land is common. This relationship with the land and all living things was (and is) at the core of Indigenous physical culture.

What is your relationship with the land and its original inhabitants? Using the Native Land Digital tool, develop a personal statement unique to you and the place in which you live, that includes the following information:

Name the Indigenous territory on which you are living. Also, name the Indigenous people(s) who live in your region.- Explain who you are, your personal/familial relationship to this land, and what treaty(s) establish your relationship with the land and its First Peoples.

- Link your acknowledgment to your personal and/or professional reasons for taking this course.

A Subsistence Way of Life

Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day North America – what some First Peoples refer to as Turtle Island – were inhabited by Indigenous populations, with rich and complex social, political, and cultural systems that existed for many millennia. During this time, Indigenous lifeways were unchallenged by foreign influences and remained land-based and environmentally responsive. Societies then used mobility as a survival strategy, sometimes travelling long distances across land or water to find food (some Indigenous groups were nomadic or semi-nomadic).

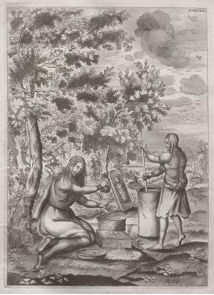

Though differing from region to region, Indigenous peoples practiced sophisticated, yet physically-demanding methods of hunting, fishing, and gathering and growing foods which ultimately helped them to lead healthy lives. Routinely performing these necessity-driven subsistence tasks meant that people stayed active from childhood to Elderhood. Indigenous men, women, and Two-Spirit peoples all performed various functions vital to the survival of their communities. Men were generally responsible for hunting as well as providing shelter and protection. Women gathered and prepared food and were honoured as the caretakers of young life. Two-Spirit peoples fluctuated between these roles and were thus held in high esteem.

Subsistence Activities

*click on the headings below to reveal more information.*

Woven into subsistence activities were culturally embedded knowledge and values about local ecologies and the edible species existing within them. Ecological knowledge of food sources and cultivation methods was passed down from one generation to the next by cultural transmission; through oral teachings, songs, storytelling, and experiences on the land. People honoured and gave thanks for the natural resources they harvested from the land and understood the need to care for nature’s balance, taking only what they needed.

Consisting mostly of flora and fauna found in their homelands (with some accessed through trade from other locales), foods comprising traditional Indigenous diets were diverse and nutrient rich. Variations in diet were attributed to differences in the geographical locations of historic Indigenous populations:

*click on the plus signs below to reveal more information about the diets of the different geographical locations*

Most traditional food-sourcing practices inherently promoted well-being by simultaneously promoting physical activity, healthy nutrition, and individual and communal well-being. In fact, modern research suggests that these three core aspects of health promotion – exercise, diet, and individual/community well-being – are closely linked to disease prevention (Burnette et al., 2018). Indeed, exerting high levels of energy on a daily basis whilst hunting or foraging for foods that generally comprised a nutritious diet, meant that issues like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity were once very rare among Indigenous peoples. These practices at the same time heightened familial and community solidarity, which enabled the continuity of other physical culture traditions.

Activity 2

Indigenous peoples possessed many attributes that enabled them to survive and thrive in the vast, natural expanses of Turtle Island (North America). They were capable of great physical efforts owing to the heavy demands of their subsistence lifestyles.

For this activity, open a new browser window and research the traditional hunting and foraging diets that existed in the territory you live in. Then, select one food item that a typical hunter-gatherer might have sought in your specified location. Contemplate the following factors:

- The location where the food item is found and how one might have historically travelled to and from that location

- The ecological knowledge that one might require for hunting or foraging the food item.

- The tools used and physical capabilities needed for hunting or foraging the food item.

- Potential health-promoting effects related to hunting or foraging the food item.

Activity 3

The Haudenosaunee, among other Indigenous peoples, traditionally begin important gatherings by offering thanks to the natural elements of life that sustain humanity.

- Listen to the voices of Mohawk language professor Ryan DeCaire and Mohawk food leader Chandra Maracle (n.d.) as they offer the Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen or The Thanksgiving Address in both Mohawk and English.

- Consider how the protocol of giving thanks relates to historical Indigenous subsistence practices and traditional concepts of sustainability.

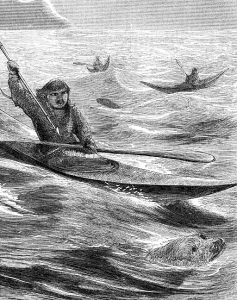

The Power of Play

Most traditional Indigenous games and sports had utilitarian purposes; activities like archery, spear throwing, and foot or canoe racing, were largely intended to condition people for their rigorous subsistence undertakings. Other activities had spiritual significance, such as lacrosse, which was (and still is) otherwise known as “The Creator’s Game”. Through play, practice, and competition, play had marked physiological benefits, including positive effects on aerobic and anaerobic fitness, body composition, bone density, and joint function. Certain traditional Inuit games for example instilled kinesthetic skills while simultaneously promoting the development of upper-extremity muscles, all in preparation for hunting marine animals with harpoons.

The “power of play” is well evidenced in Burnette et al.’s (2018) article “Living off the Land,” which describes playful, land-based physical interaction with others as a having ancient survival benefits, not because people were consciously trying to reap the health benefits, but rather because play is fun: “Therein lies the true power of play—we choose to make it a priority because it enhances our enjoyment of life… Moreover, activity done in a natural outdoor environment also bestows additional benefits for health and wellbeing, including reductions in stress levels, elevated mood and enhanced memory.” (O’Keefe & Lavie, 2020, p. 154)

“Therein lies the true power of play—we choose to make it a priority because it enhances our enjoyment of life… Moreover, activity done in a natural outdoor environment also bestows additional benefits for health and wellbeing, including reductions in stress levels, elevated mood and enhanced memory.” (O’Keefe & Lavie, 2020, p. 154)

A great variety of traditional games and sports were developed for the sheer love of play, but also evolved as forms of diplomacy and conflict resolution. While somewhat different now from the original versions, many traditional games and sports are still enjoyed (recreationally and competitively) by Indigenous peoples today.

Note: Indigenous sport, games, and competition will be covered in greater depth in Stepping Stone 3.

Activity 4

Read “A Hunter-Gatherer Exercise Prescription to Optimize Health and Well-Being in the Modern World.”

- What health and wellness benefits does the article suggest as being products of a “Hunter-Gatherer Exercise Prescription”?

Activity 5

Look at the examples of traditional Indigenous games and sports depicted below. Select one image that piques your interests or connects with you.

Consider the following questions:

- What do you observe in the image? What does it make you think, feel, or wonder?

- What physical requirements for playing the depicted game or sport can you surmise?

- What do you perceive might be some of the health-promoting factors (i.e. the “power of play”) associated with the game or sport depicted in the image?

Health and Healing

Indigenous peoples had (and have largely maintained) fully functional systems of health knowledge that were practiced within the contexts of their specific ways of knowing and being(First Nations Health Authority, n.d.). Like other elements of life, health practices – such as herbal medicines, hygiene customs, ‘‘smudging’’ (burning aromatic medicine plants to produce smoke), and participating in cultural healing ceremonies – were formed by the needs of the community and tied inextricably to place. The local environment likewise shaped the medical expertise and approaches used by shamans, midwives, and healers.

Healers were highly knowledgeable about plant, animal, and mineral-based medicine usages, as well as physical or hands-on therapeutics. Although healing methods varied between cultures, most were based in a wholistic worldview that honoured the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of health and well-being. Much like today, central importance was placed upon the concept of maintaining healthful balance, within the individual and between the individual, the community, and the natural world (Obomsawin, 2007).

The Medicine Wheel is an important part of Indigenous healing. It represents balance within the individual (i.e., in the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual domains) as well as interconnectedness between the individual, their community, and all other aspects of creation. The Medicine Wheel also represents four sacred medicine plants that are important to many traditional healing practices:

Preventive health practices were also valued, including regular bathing and the abundant drinking of water, deep breathing, and physical and spiritual exercises, in addition to special geriatric and child care methods (Obomsawin, 2007). Children were commonly raised and nurtured not only by their parents but by their extended families. Elders too were cared for by their communities, as revered vessels of experience and wisdom. By working together to ensure that people’s needs were met, communities thrived – everyone contributed to the overall well-being of the group. When an individual fell sick, their community would provide support. It comes as no surprise then that the oral traditions of many Indigenous peoples suggest that ancient populations were large, healthy, and flourishing during pre-colonial times. Conversely, it is also made clear by this oral record that Indigenous populations would be abruptly transformed in the wake of first contact.

Activity 6

The Medicine Wheel has traditionally been used to guide and support the development of a balanced individual. It reminds one of the need to balance all four aspects of self – the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual domains of wholistic well-being.

- How do you personally conceptualize these four aspects of wholistic well-being?

- Using The Medicine Wheel conceptualized by Curve Lake First Nation as a guide, take a moment to draw your own Medicine Wheel. Fill in this Medicine Wheel with activities that you conduct which positively influence your mental, physical, emotional and spiritual health (e.g. mental: school, physical: playing sports, emotional: social experiences, spiritual: meditation). Some activities may interconnect with multiple quadrants of the Medicine Wheel.

- What does your Medicine Wheel tell you about your needs for health and balance?

Wellness Break

Watch Medicine Wheel: Mental Meditation (1:54) and take a moment to re-calibrate.

- Sit in a comfortable, upright position.

- Close your eyes.

- Breathe deeply.

- Relax your body.

- Be aware of any thoughts or feelings you are experiencing.

- When your mind wanders, focus on your breathing.

- Open your eyes when you are ready.

Stepping Stone 1 Summary

In this Stepping Stone, you were introduced first to the important relationship between Indigenous physical culture and the land. You then looked at the health-promoting effects of traditional subsistence lifeways and explored play as a mechanism for physical development. We also discussed traditional Indigenous healing systems and invited you to think about health from a wholistic perspective. Finally, we provided you a glimpse into the historical state of well-being in Indigenous communities prior First Contact. Being aware of this history will help you in building stronger relationships with the Indigenous people you work with in your future career. It is the beginning of a truth-seeking journey that will form the foundations for reconciliation.

Cool-down Activity

Before beginning this Stepping Stone, you were asked to look at the image below and to consider some guiding questions.

Before beginning this Stepping Stone, you were asked to look at the image below and to consider some guiding questions.