Job Analysis

Job Analysis

Job Analysis is a systematic process used to identify and determine, in detail, the particular job duties and requirements and the relative importance of these duties for a given job. It allows HR managers to understand what tasks people actually perform in their jobs and the human abilities required to perform these tasks. Job analysis aims to answer questions such as:

- What are the specific elements of the job?

- What physical and mental activities does the worker undertake?

- When is the job to be performed?

- Where is the job to be performed?

- Under what conditions is it to be performed?

A major aspect of job analysis includes research, which may mean reviewing job responsibilities of current employees, researching job descriptions for similar jobs with competitors, and analyzing any new responsibilities that need to be accomplished by the person with the position.

For HRM professionals, the job analysis process results feed job design, work structure and process engineering, as well as team and department structure. The data collected informs a multitude of HR policies and processes. For this reason, job analysis is often referred to as the ‘building block’ of HRM. Here are some examples of how the results of job analysis can be used in HRM:

- Production of accurate job postings to attract strong candidates;

- Identification of critical knowledge, skills, and abilities required for success to include as hiring criteria;

- Identification of risks associated with the job responsibilities to prevent accidents;

- Design of performance appraisal systems that measure actual job elements;

- Development of equitable compensation plans;

- Design training programs that address specific and relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities.

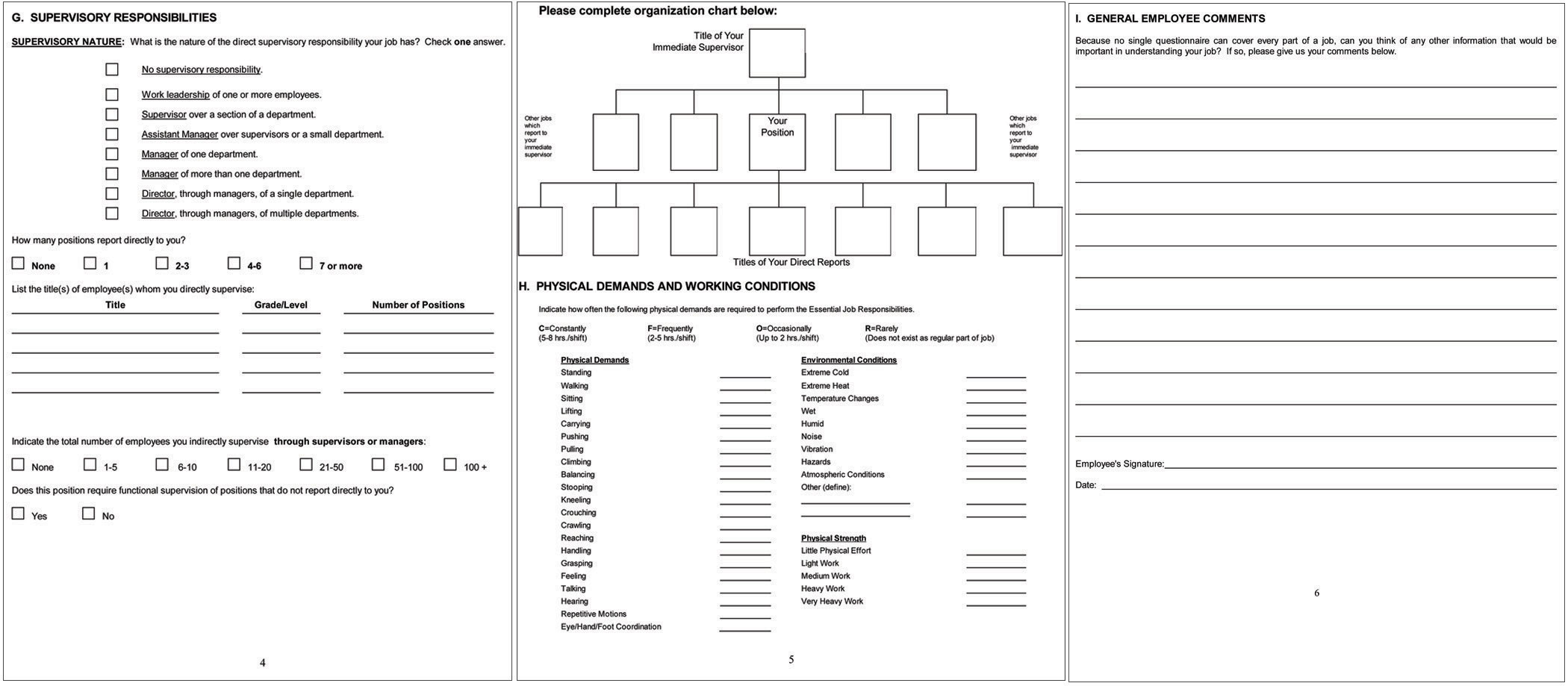

Figure 3.1. This flowchart shows the process of conducting a job analysis.

The Job as Unit of Analysis

Any job, at some point, needs to be looked at in detail in order to understand its important tasks, how they are carried out, and the necessary human qualities needed to complete them. As organizations mature and evolve, it is important that HR managers also capture aspects of jobs in a systematic matter because so much relies on them. If HRM cannot capture the job elements that are new and those that are no longer relevant, it simply cannot build efficient HRM processes. Take the job of university or college professor, for example. Think of how that job has changed recently, especially in terms of how professors use technology. Ten years ago, technology-wise, a basic understanding of PowerPoint was pretty much all that was required to be effective in the classroom. Today, professors have to rely on Zoom, Moodle, and countless other pedagogical platforms when they deliver their courses. These changes point to a profound change in the job. It is critical that this change be captured by the organization’s HR department in order for the organization to achieve their educational mission. With this information, departments can now select professors based on their level of technological savvy, develop training programs on various platforms, and evaluate/reward those professors who are embracing the technological shift, etc.

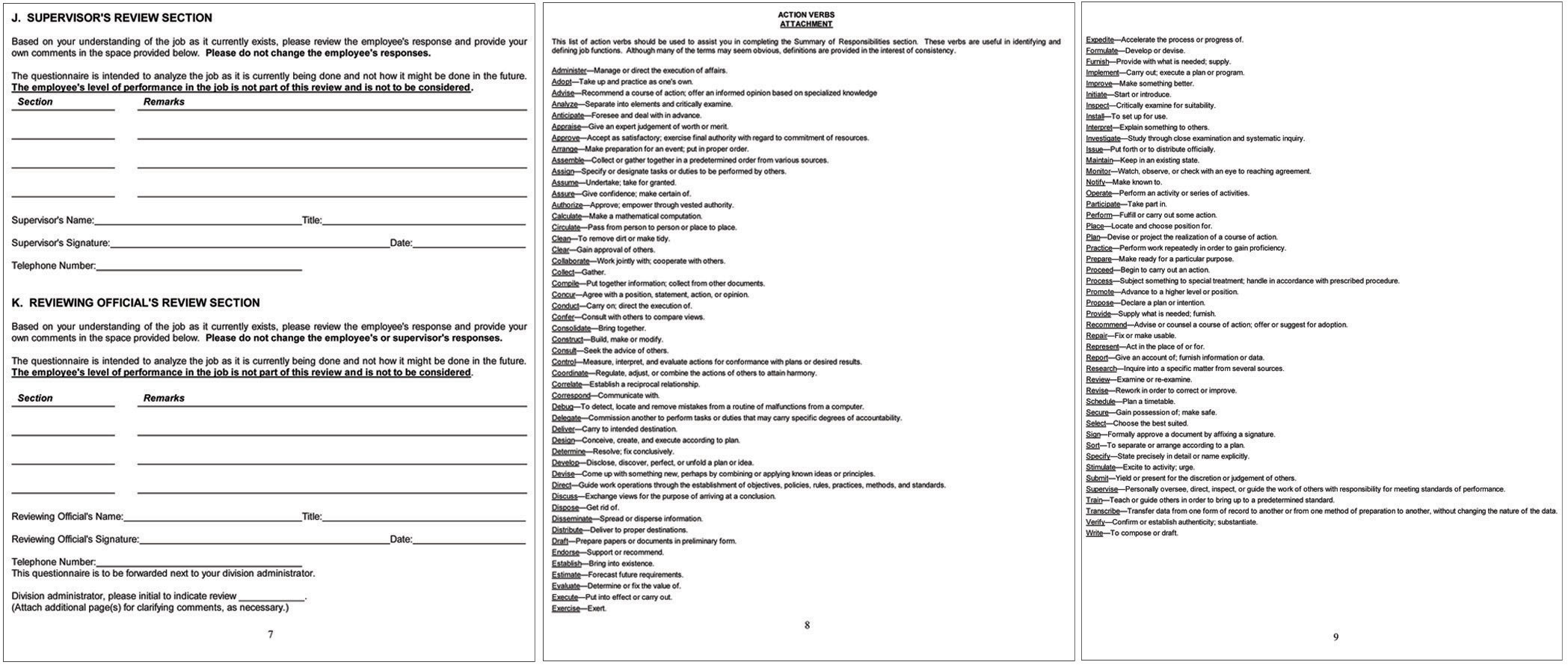

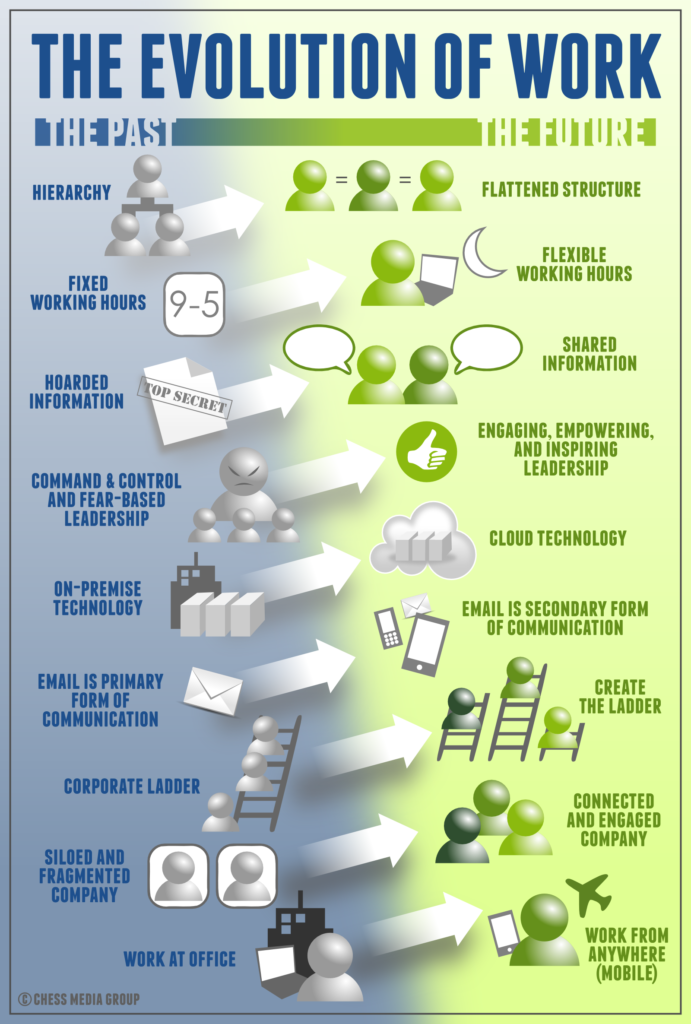

Figure 3.2 – This infographic summarizes what the future of work looks like

While job analysis seeks to determine the specific elements of each job, there are many studies that have looked at how jobs are evolving in general. These mega trends (see Figure 3.2) are interesting because they not only point towards new characteristics of jobs but also towards an acceleration in the rate of change. For example, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has just begun to make its impact on the world of work. In the next decade, many tasks will be replaced and even enhanced by algorithms. Project yourself, if you can, 50 years from now. Do you think that transportation companies will rely on truck drivers? Autonomous vehicles are already a reality, this promises to be incredibly efficient. Do you think that customer service representatives will be required? We are already having conversations with voice-recognition automated systems without realizing it. Let’s push this to more sophisticated jobs: medical doctors. The diagnosis of illness requires a vast amount of knowledge and, in the end, judgment. Who would bet against the ability of computers able to process billions of bits of information per second not to outperform the average doctor? Bottom line: the AI revolution is not coming, it is already here.

Determine Information Needed

The information gathered from the job analysis falls into two categories: the task demands of a job and the human attributes necessary to perform these tasks. Thus, two types of job analyses can be performed: a task-based analysis or a skills-based analysis.

Task-based job analysis

This type of job analysis is the most common and seeks to identify elements of the jobs. Tasks are to be expressed in the format of a task statement. The task statement is considered the single most important element of the task analysis process. It provides a standardized, concise format to describe worker actions. If done correctly, task statements can eliminate the need for the personnel analyst to make subjective interpretations of worker actions. Task statements should provide a clear, complete picture of what is being done, how it is being done and why it is being done. A complete task statement will answer four questions:

- Performs what action? (action verb)

- To whom or what? (object of the verb)

- To produce what? or Why is it necessary? (expected output)

- Using what tools, equipment, work aids, processes?

When writing task statements, always begin each task statement with a verb to show the action you are taking. Also, do not use abbreviations and rely on common and easily understood terms. Be sure to make statements very clear so that a person with no knowledge of the department or the job will understand what is actually done. Here are some examples of appropriate task statements:

- Analyze and define architecture baselines for the Program Office

- Analyze and support Process Improvements for XYZ System

- Analyze, scan, test, and audit the network for the Computer Lab

- Assess emerging technology and capabilities for the Computer Lab

- Assist in and develop Information Assurance (IA) policy and procedure documents for the Program Office

- Automate and generate online reports for the Program Office using XYZ System

- Capture, collate, and report installation safety issues for XYZ System

- Conduct periodic facility requirements analysis for the Program Office

- Copy, collate, print, and bind technical publications and presentation materials for the Program Office

Competency-based job analysis

A competency-based analysis focuses on the specific knowledge and abilities an employee must have to perform the job. This method is less precise and more subjective. Competency-based analysis is more appropriate for specific, high-level positions.

Identify the Source(s) of Data

For job analysis, a number of human and non-human data sources are available besides the jobholder themselves. The following can be sources of data available for a job analysis.

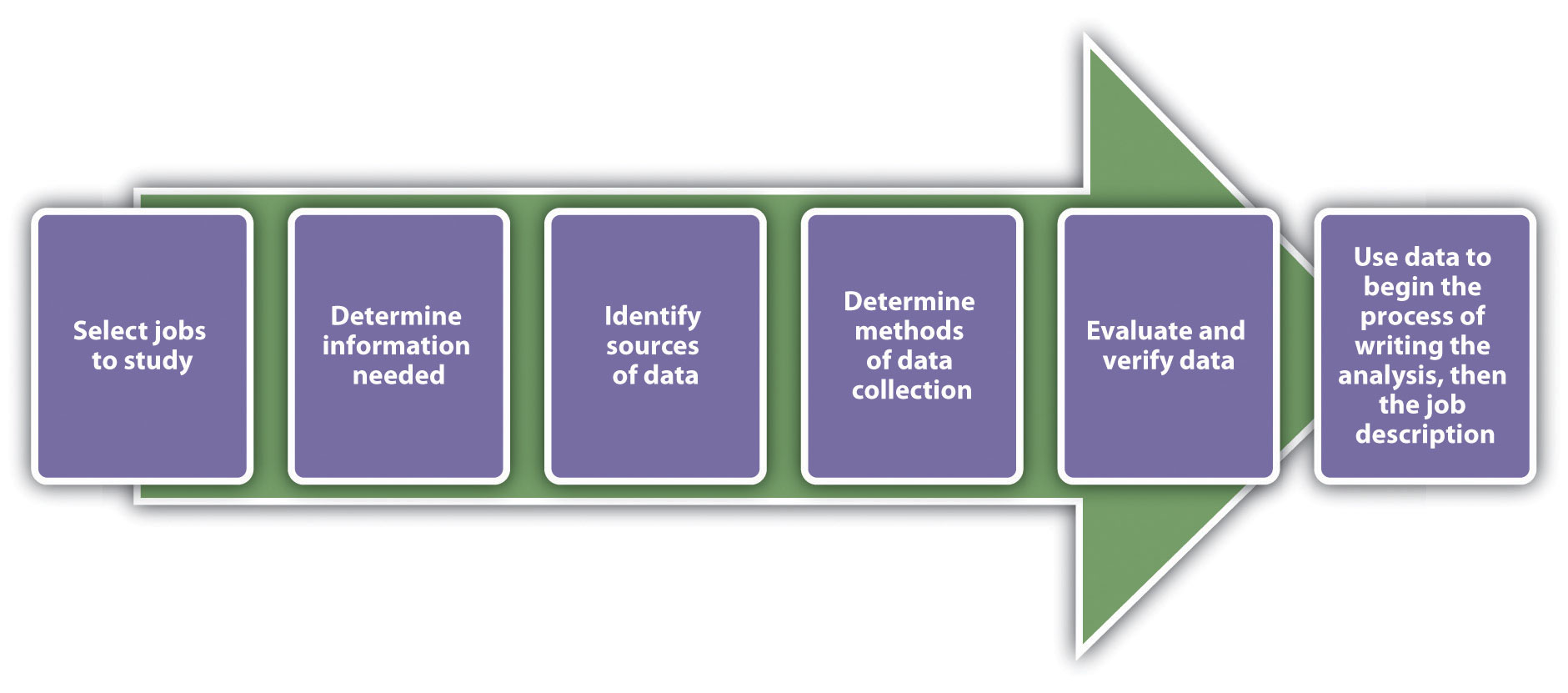

Figure 3.3.

| Type of Source | Possible Sources |

|---|---|

| Non-Human Sources |

|

| Human Sources |

|

Determine Methods of Data Collection

Determining which tasks employees perform is not easy. The most effective technique when collecting information for a job analysis is to obtain information through direct observation as well as from the most qualified incumbent(s) via questionnaires or interviews. The following describes the most common job analysis methods.

Open-ended questionnaire

Job incumbents and/or managers fill out questionnaires about the Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities (KSA’s) necessary for the job. HR compiles the answers and publishes a composite statement of job requirements. This method produces reasonable job requirements with input from employees and managers and helps analyze many jobs with limited resources.

Structured questionnaire

These questionnaires only allow specific responses aimed at determining the nature of the tasks that are performed, their relative importance, frequencies, and, at times, the skills required to perform them. The structured questionnaire is helpful to define a job objectively, which also enables analysis with computer models. This questionnaire shows how an HR professional might gather data for a job analysis. These questionnaires can be completed on paper or online, many are available for free.

Interview

In a face-to-face interview, the interviewer obtains the necessary information from the employee about the KSAs needed to perform the job. The interviewer uses predetermined questions, with additional follow-up questions based on the employee’s response. This method works well for professional jobs.

Observation

Employees are directly observed performing job tasks, and observations are translated into the necessary KSAs for the job. Observation provides a realistic view of the job’s daily tasks and activities and works best for short-cycle production jobs.

Work diary or log

A work diary or log is a record maintained by the employee and includes the frequency and timing of tasks. The employee keeps logs over a period of days or weeks. HR analyzes the logs, identifies patterns and translates them into duties and responsibilities. This method provides an enormous amount of data, but much of it is difficult to interpret, may not be job-related and is difficult to keep up-to-date. See Job Analysis: Time and Motion Study Form.

Evaluate and Verify the Data

Using the Data to Yield a Job Analysis Report

Once the job analysis has been completed, it is time to write the job description. These are technical documents that can be very detailed. For example, here is a job analysis report conducted in the US by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) within strategic initiatives focusing on four occupations with primary responsibilities for safety and risk data collection, analysis, and presentation: Operations Research Analyst, Engineer, Economist, and Mathematician. In a totally different category of work, here is another one describing the job of Amusement and Recreation Attendant.

References

Hackman J. R. and Greg R. Oldham, “Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 16, no. 2 (August 1976): 250–79.