Chapter 16: How to ‘Student,’ or Setting Yourself Up For Success in College

Coping with workload stress

When you are in post-secondary, you might have anywhere from 4-8 courses, depending upon your program. The amount of time and energy that is required to be successful in school is tremendous, and with that comes immense pressure and stress. Stress is a good thing because it lets us know that we’re invested and care about what is happening; however, for many people, work/course load stress can be crippling.

One of the first things that students should keep in mind is that you are still learning. No one expects perfection; if you knew it all, you wouldn’t be in school. Remember, too, that your professors were once students who started our just where you are now. Though it may not seem like it now, they crammed last minute, skipped classes, partied too hard, failed exams, and struggled with their mental/emotional health. Your professors, therefore, can be a great source of advice for how to balance work/school/life. You might be surprised at the tips and tricks that they have picked up over the years!

Identifying stress triggers

We all have different stress triggers – that is, things or situations that cause you anxiety and stress. It can be tests, presentations, group work, living situations, relationships, finances… there’s an almost endless list. The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety has a great website that discusses stress and provides some strategies for helping to cope.

Getting help and support

Sheridan has many resources available to help support students who may be facing struggles:

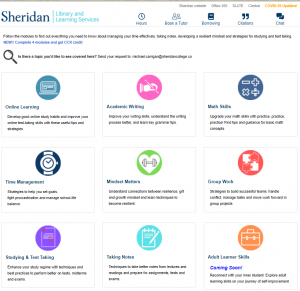

The Sheridan Academic Skills Hub has information on all sorts of topics related to learning, mental health, and student life:

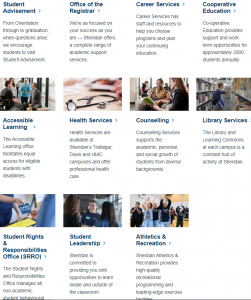

Sheridan Student Services offers a host of different supports designed with Sheridan student needs in mind, including free counselling, health/wellness, career counselling, free academic tutoring, etc:

Approaching your professor

Your professors may seem intimidating to you; they are the people who impart the knowledge that you need and have a tremendous impact on your education. And, at some point or another, you are going to have to reach out to them because you need something. There are certain good practices to use when you contact or speak to your professor…

Doctor? Professor? What do I call them?

The title “professor” is one that is given to most people who teach at a post-secondary institution (some have the title “lecturer”). Universities often have “rankings” for professors, based upon how far they have progressed in their careers (ex. Associate Professor, Adjunct Professor). Calling your instructor “professor” is an appropriate form of address.

Having said that, some professors also have the title “doctor.” These folks have earned a PhD or MD in their field and the title is a sign of respect for the time and contributions that they have made to their respective field(s). Some faculty will hold both titles, but the title “doctor” typically outranks “professor.” While “professor” is the safest route to go, you may encounter some faculty who insist upon being called “doctor.”

Some faculty that you encounter will ask you address them by their given (first) name. If they’ve said that’s what they prefer, go with that.

Sending an Email

When you go to email your professor, keep in mind that they can have hundreds of students. There are a few things to consider when you email:

- Be sure to check all of your resources before going to the professor. Look in the syllabus, in your online class section (SLATE), ask you peers, etc.

- Include your class date and time. It’s a good idea to include this in the Subject line because professors often teach multiple sections of the same course.

- Be polite. Students don’t typically email their professors to ask how their day was. If you’re emailing or reaching out, you need something from your professor. Politeness goes a long way. You might be upset or angry about something to do with the class, but sending an aggressive or defensive email will only make the situation worse.

- Be specific about the issue. If you want to meet with them, give them an indication as to why. Imagine getting an email from your professor that simply says: “Please see me after class.” You’d probably get pretty anxious. Your professors experience the same thing, so while you don’t have to get into all of the particulars, give them a heads up about what you want to discuss. Something like: “could we set up a time to discuss my last essay” is perfectly fine. This allows the professor time to review the paper and feedback before you arrive so that you can have a more productive discussion.

- Ask for what you need directly and supply any necessary information upfront. If you need to ask for an extension, ask for it. Many student grow up in a “Guess-Culture” where they are taught it’s impolite to ask for things. Here’s a great excerpt from an article by the Guardian on the subject:

In Canada, professors expect students to ask directly for what they need because they often see guess-culture as inefficient and even passive-aggressive. Learning how to ask for something politely is a valuable skill. Part of asking for something also means including any necessary information. For example, if you want an extension, include a copy of your doctor’s note in the email since you know that the professor is going to ask you for it anyway. - Avoid speaking on behalf of an undefined group. Many professors get irritated when they receive emails with statements like: “the class and I” because: a) it appears like you’re ganging up on the professor, b) you’re hiding behind a bandwagon fallacy, and c) it doesn’t allow the professor to fairly address the issue with everyone involved. If you have concerns that you wish to address with your professor, speak for yourself and come prepared to suggest alternative plans/ideas.

- Don’t expect an immediate reply. Email and the internet have given us unrealistic expectations about timeframes for answers. Your professor could be busy with work/life, or maybe they need some time to think about the answer. A good rule of thumb is that if you don’t hear back after 2 business days, send a polite follow up email.

Talking to Your Professor in Person

Each professor is different in terms about when they prefer to be approached by students in person. Most professors hold office hours where students are welcome to come by and see them. Some prefer that you email them to set up an appointment. The toughest scenario to navigate is how to approach the professor in the classroom. There are typically three appropriate times to do this:

- Before the class begins.

- During official breaks in the class.

- After the class has ended.

Depending on the professor and their own schedule, they may prefer to speak to you at different times. Some faculty spend the time before class getting set up and mentally preparing for the lesson and so don’t appreciate being distracted. Some use the breaks in class to go to the bathroom and such. Some have to leave directly after class ends for personal or work reasons (perhaps they have another class or meeting – professors typically are not on campus from 9:00-5:00).

The best strategy is to ask the professor when they prefer to be approached with questions during the period. Interrupting a lesson or discussion to ask questions that are related only to yourself is typically frowned upon because it takes away from the shared class time; however, if the group would benefit from the answer (ex. clarification about an upcoming assignment), then yes, you should definitely ask during class.

Asking for Letters of Reference

It is quite common for students to approach faculty for letter of reference when they are applying for scholarships, other programs, grants, etc. Here are a few things to ask yourself before you approach a professor:

- Was I a positive contributor in the class? Can the professor speak highly of me and my work?

- Is this professor’s class relevant to the application? Are they qualified to speak to my experience for this application?

- Have I left a reasonable amount of time for the professor to complete the letter? A good amount of time is at least 2 weeks before your application is due.

- Do I have a resume prepared that I can show the professor if they ask? Oftentimes, the professor will ask for this information to help them write a letter that is specific to your needs.

A good way to approach the professor is to ask if they are able to give you a positive (or strong) letter of reference. Be prepared that some faculty may say no for different reasons. They may not know enough about you, they may be too busy, or they may view their experience with you differently. Since students often don’t get to see a copy of the letter that the faculty member submits, it’s good to know upfront if the professor is able to speak of you positively.

Building a Relationship

Building a relationship with your professor is an important part of the post-secondary experience. The key here is to maintain a professional relationship that doesn’t blur the boundaries between personal life and the classroom. Professors can lend a sympathetic ear, but they’re not (usually) academic counsellors or mental health professionals.

The best bet it to take your cue from the professor. Some will actively encourage less formal relationships with their students while others will maintain a very clear separation. Some professors like to laugh and joke around and others see the classroom as a serious place of learning. Some will be flexible with assignments and deadlines and others will not.

A good way to “feel” out your professor is to pay attention to their introduction on the first day: it will tell you a lot about them and set the tone for their classroom. It can help to remember a few things about your professors:

- They’re humans too. They have bad days, crises in their personal lives, and insecurities. Students can assume wrongly that if the professor is in a bad mood, then it’s about them. And sometimes it can be! For example, one of the most frustrating things for a professor is a class that doesn’t do the assigned readings because it throws off the lesson plan and forces us to adapt on the fly. But, sometimes it’s not about you at all. Cut them some slack if they’re having an off day.

- Their mistakes are very public. Your professors do public speaking for a living. Imagine how anxious the thought of a presentation makes you, and now imagine doing it almost every day. Mistakes will happen because we’re human. It can be helpful to remember that every lecture/class is your professor giving a presentation. And, just like anyone else, if our presentations go badly or flop, it can affect how we engage and approach the class. Be good audience members: smile, nod, ask (good) questions, and engage with us. Trust me, it will make you stand out as a student.

- They may have only had minimal training as an educator. Many of your professors come from industry, which means that they are subject matter experts and may never have had an opportunity to take seminars or courses on how to teach. Teaching certifications or qualifications are not mandatory at the post-secondary level in North America (though they do help immensely). If you have a “bad” professor, it’s a very real possibility that they’re still learning how to teach! Try to be patient with them.

Professor Pet-Peeves: Things that Drive Us Crazy Inside and Outside of the Classroom

Many of your professors have either been in academia for a long time or maybe have never left. It can be easy for us to forget that post-secondary etiquette is not always obvious to students. Here are some of the things that you want to avoid doing as a student:

- Side conversations or texting while we’re speaking. This one is fairly self-explanatory, but many students don’t seem to realize that they’re not as quiet or subtle as they believe. When a professor is at the front of the room, they can hear and see pretty much everything. Trust me: seeing a student with their head bowed and hands fiddling in their laps is a dead give-away that you’re texting. We see it and it’s rude. Don’t do that.

- Students that challenge us rudely. Speaking of rude, if you want to challenge us or make a point, don’t be a jerk or arrogant about it. Most of your professors love to debate and are hardwired to engage with complex ideas, so we won’t be offended if you disagree with us. However, if you’re condescending or rude, we’re more likely to throw down academically and show you what we really know.

- Students that dominate conversations. It can be tempting to over-engage in your classroom discussions, especially if no one else is speaking. Most of us are uncomfortable in long periods of silence. However, if others don’t get a chance to speak, then your professor has a hard time gauging if everyone is understanding the content.

A good rule of thumb: try to limit your contributions to 3-5 times per class and, when you are speaking, keep you point to about 30-45 seconds. - Last-minute requests for extensions. Things come up. We know that. But when you fail to prepare ahead of time and flood our inboxes at last minute with requests for extensions, it gets irritating. Try to make requests like this a couple of days in advance if you are able to do so.

- Vague or demanding emails. We discussed email etiquette earlier in this chapter, but it’s worth mentioning again. Some profs will respond right away and others could take 2-3 days to get back to you, depending up their workload and inbox. Be patient and give them time to responds. Making sure to give specific details and information in your emails will help to speed the process up.

- Teaching to black screens. In the post-pandemic world, many of us teach online to black screens. Look, we get it. You might be in your pajamas, or your room is a disaster. Maybe there’s lots of noise, pets, family members, etc. running around. But the majority of professors get into teaching because they enjoy interacting with the students. And, to return to an earlier point, teaching is just presenting, and it’s awful to present when you have a sea of black screens. If you want to stand out in an online class, turn on your camera and engage with the professor.

- Grade grubbing. Grade grubbing is where students believe that grades can be haggled or negotiated with the professor. Two key tips here: first, if you want to discuss your grades, always make sure to do it with the professor privately. Second, while we know that grades are very important, don’t be the student that nitpicks over every little detail. You should absolutely speak with your professor if you believe there to be an error or you don’t understand where you went wrong in the assessment, but do so respectfully. It will get you a lot further in the course and with the professor than being combative.

TIP: don’t go into a meeting and try to argue with the professor over points and answers. Listen, provide clarification when appropriate, and show a willingness to learn. If there’s a calculation error in your mark, point it out politely and calmly. You might be surprised as how well the meeting goes!

Video source: https://youtu.be/I9UB051LLSg

Dealing with Disappointing feedback & grades on assignments

Having graded assessments returned to you is a vulnerable experience because it feels as though those marks are an evaluation and judgement of you: your intelligence, your work effort, your potential, and your future. It’s important to remember that grades are a form of currency in post-secondary studies and are used to help determine how far you’ve progressed in your learning journey.

Not everyone will grasp material at the same pace or in the same way. Realizing that grades can have an emotional impact upon us (positively and negatively) can give us some insights into strategies that are helpful for processing assessment feedback.

So what do you do when your grade is disappointing? Here are a few suggestions:

- Set it aside and wait until the emotional response has calmed down. Once you’re in a better place, read over the comments and feedback carefully. These points will often help you understand what you may have missed.

- Have someone you trust look over your work and summarize the feedback for you. You might ask them to tell you three things that the professor said that you need to focus upon in future assignments, or paraphrase the comments. Oftentimes, when it’s a friend or loved one giving us the feedback, it comes across more gently. The information is still the same, but the delivery can make all of the difference.

- Take some time to reflect upon what went wrong. Be honest with yourself. Did you cram for the test? Did you write the paper last minute? Did you misunderstand the instructions? Oftentimes, it’s not that we don’t understand the material, but rather that we didn’t provide the information that the professor was looking for in our answer.

- Check your expectations. Some students are used to getting A grades and struggle to accept that the work in question might be B level work. It can be a shock when students move from high school to post-secondary and the expectations of their work jumps significantly. Moreover, your expectations of yourself may just simply be too high. While it’s possible to get 90s in your work in post-secondary, it’s certainly not the norm. If you’re putting too much pressure upon yourself, it’s only going to create more stress and anxiety.

- Make a habit of not discussing or asking others about their grades. This is a hard one because of peer pressure. While it’s natural to want to rank ourselves and see how others did, talking about grades usually ends up with one of two outcomes: a) You feel worse about yourself because someone did better than you; or b) You make someone else feel worse about their work. Often people discuss grades because they seek validation and reassurance. Try to reflect on your own progress. Did you do the best that you could have within your given circumstances?

- Ask the professor for a meeting to sit down and go over the paper. Try to make this request 2-3 days after you receive the feedback so that you’ve had time to reflect and emotions have settled. Go to the meeting with specific questions based upon the feedback or results. Asking: “how can I do better?” is a difficult question for faculty to answer. Asking something like: “I see that I struggled most in _____ section. Could you give me some advice about how to answer this type of question most effectively?” will yield better information for the next assessment.

- Remember that feedback is meant to help. Sometimes, the feedback is going to feel harsh. Your professors are trying to teach you and equip you as best they can, and it’s their job to provide you with feedback. It can be helpful to remember that professors are people too, and sometimes, they don’t give feedback in the best way (it’s a tough skill to master!). Try to see past how something is being said and understand what is being said. If the professor didn’t care, they wouldn’t bother trying to correct your work.

- Get extra help. Look into tutoring, other online resources, speak with other students who understand the material, go to office hours/tutorials. No one can be good at everything and there is no shame in needing some extra help.

Video source: https://youtu.be/5ad6grll-ak

online learning

The prevalence of online and hybrid courses is a new post-pandemic shift. Until 2019, digital learning was not nearly as popular, but during the COVID pandemic, the world saw that it is possible to teach and learn online effectively (though it’s also possible to bomb at it as well).

Depending upon your course, your online learning experience will differ. One of the biggest factors is asynchronous classes vs. synchronous classes:

As you can see, asynchronous learning calls for a lot more independence in terms of problem solving, motivation, and discipline because your professor is a resource, not the main source of your learning.

So, how can you make the most out of an online class? Check out this video for some tips and strategies:

Video source: https://youtu.be/HsWYxfVzX_U