Chapter : Research Topics, Questions, and Thesis Statements

Coming Up With a research Topic

A controversial topic is one on which people have strong views. Imagine the type of discussion that can become really heated, usually when the subject is something people are passionate about. But a person who is passionate about a particular issue does not necessarily mean he or she recognizes the merits of the other view (although that often happens); it just means that the person has collected evidence (from a variety of sources) and synthesized those ideas to arrive at a particular point of view. When you are trying to choose your topic for your persuasive paper, it is easier if you choose a topic about which you feel very strongly. You probably have realized by this point that when you are writing, it is a lot easier to write about a topic you already have some background knowledge on, and something you are extremely interested in. This helps to engage you and keep you interested in the writing process. No matter the topic you eventually decide to discuss, there are a few things you need to think about before you begin the writing process. You will need to make sure your subject is:

- Significant. Is a discussion of this topic one that has the potential to contribute to a field of study? Will it make an impact? This does not mean every discussion has to change lives, but it needs to be something relatively important. For example, a significant topic would be to convince your reader that eating at fast-food restaurants is detrimental to people’s cardiovascular system. A less significant discussion would be if you were to try to convince your reader why one fast-food restaurant is better than another.

- Singular. This means you need to focus on one subject. Using the fast-food restaurant example, if you were to focus on both the effects on the cardiovascular and endocrine system, the discussion would lose that singular focus and there would be too much for you to cover.

- Specific. Similar to the point above, your topic needs to be narrow enough to allow for you to really discuss the topic within the essay parameters (i.e., word count). Many writers are afraid of getting too specific because they feel they will run out of things to say. If you develop the idea completely and give thorough explanations and plenty of examples, the specificity should not be a problem.

- Supportable. Does evidence for what you want to discuss actually exist? There is probably some form of evidence out there even for the most obscure topics or points of view. However, you need to remember you should use credible sources. Someone’s opinions posted on a blog about why one fast-food restaurant is the best does not count as credible support for your ideas.

Video source: https://youtu.be/zxMsZsNw47U

A note about choosing topics for your assignments in this course:

In this course, we require students to pick a research topic for the term; however, certain topics can be extremely sensitive and/or a potential trigger for students in the classroom. It is important to remember that the Sheridan Student Code of Conduct states:

- Sheridan students have the right to be treated in a manner which is respectful, honest, and free from discrimination or harassment consistent with the Ontario Human Rights Code and any applicable Canadian law.

- Sheridan students have the responsibility to treat other members of the Sheridan community in a manner which is honest, respectful and free from discrimination or harassment consistent with the Ontario Human Rights Code and any applicable Canadian law.

Your professor is obligated to maintain a safe and respectful learning environment in the classroom that is free of discrimination and harassment. So, while controversial topics can be a wonderful source of debate and discussion, they must be handled in a way that is fair, respectful, and meets the Student Code of Conduct guidelines. Please note that your professor may set limitations on topics related to gender, sexuality, religion, etc. for the mental health and safety of the classroom.

Self-Practice Exercise

In previous chapters, you learned strategies for generating and narrowing a topic for a research paper. Review the list of general topics below. Also, think about which topics you feel very strongly.

Freewrite for five minutes on one of the topics below. Remember, you will need to focus your ideas to a manageable size for a five– to seven–page research paper.

You are also welcome to choose another topic; you may want to double-check with your instructor if it is suitable. It is important to remember that you want your paper to be unique and stand out from others’; writing on overly common topics may not help with this. Since we have already discussed the death penalty as a form of punishment in the last chapter and already developed ideas, you should probably not choose this topic because your instructor wants you to demonstrate you have applied the process of critical thinking on another topic.

Identify the key words you will use in the next self–practice exercise to preliminary research to narrow down your topic.

Some appropriate controversial topics are:

- Illegal immigration in Canada

- Bias in the media

- The role of religion in educational systems

- The possibility of life in outer space

- Modern day slavery around the world, ie. Human trafficking

- Foreign policy

- Television and advertising

- Stereotypes and prejudice

- Gender roles and the workplace

- Driving and cell phones

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper, but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

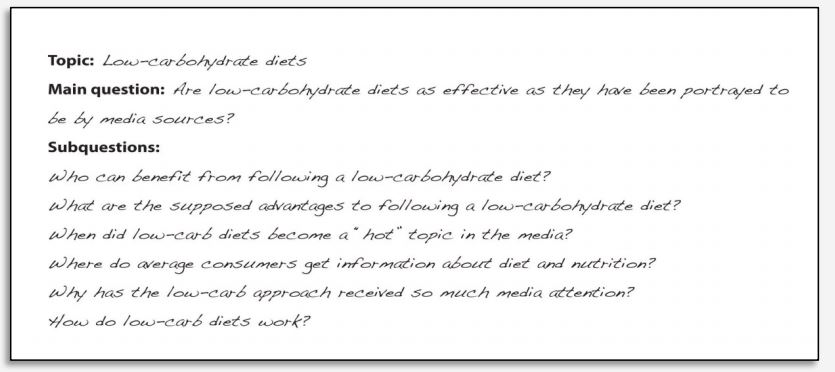

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer that main question.

Video source: https://youtu.be/GJm1GPYEXhw

Self-Practice Exercise

Create a research question you would like to find the answer to through your research and persuasive paper development. This is something you will use to help guide you in your writing and to check back with to make sure you are answering that question along the way.

Collaborate with a partner and share your questions. Describe your topic and point of view and ask your partner if that question connects to that topic and point of view.

Creating a thesis statement

For our purposes, there are three types of thesis statements: explanatory, argumentative, and analytical theses.

Video source: https://youtu.be/bamGJE2pfHQ

The persuasive or argumentative essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic (we cover this more in-depth later in this textbook). The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

You have likely been taught the need for a thesis statement and its proper location at the end of the introduction. And you also likely know that all of the key points of the paper should clearly support the central driving thesis. Indeed, the whole model of the five-paragraph theme hinges on a clearly stated and consistent thesis. However, some students are surprised—and dismayed—when some of their early college papers are criticized for not having a good thesis. Their professor might even claim that the paper doesn’t have a thesis when, in the author’s view it clearly does.

So, what makes a good thesis in college?

- A good thesis is not obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable. In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the non-obvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice,” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified. Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a well specified thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it is so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis.

- A good thesis includes implications. Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency.[1] That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

- A good thesis is not limited to one sentence. When students hear “thesis statement” they often assume that “statement” means “one sentence”. It is incorrect. Think about your thesis statement like a witness statement that you would give to the police or in court: it’s not going to be one sentence; rather, you’ll be giving an argument that explains what you saw/noticed, what you inferred, what you concluded, and why. You’ll be asked to provide details (evidence) that will support your position. So, when you think about it, thesis and essay writing isn’t that far off from providing testimony!

Version A:

Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade.

Version B:

Linen served as a form of currency in the ancient Mediterranean world, connecting rival empires through circuits of trade. The economic role of linen raises important questions about how shifting environmental conditions can influence economic relationships and, by extension, political conflicts.

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your professors who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning.

Video source: https://youtu.be/Fjfdrsjav-c

DEALING WITH COMMON THESIS STATEMENT PROBLEMS

CONSTRUCTING AN EFFECTIVE THESIS STATEMENT

THE THREE-STORY THESIS MODEL

How do you produce a good, strong thesis? And how do you know when you’ve gotten there? Many instructors and writers find useful a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.:[2]

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

-

- One-story theses state inarguable facts.

- Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point.

- Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications.[3]

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings about its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not. In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together.

To outline this example:

- First story: Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story: While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story: Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis:[4]

- First story: Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story: However, in her work we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story: Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story: Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the light brown apple moth (LBAM), an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story: Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story: Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Re-evaluate Your Working Thesis

A careful analysis of your notes will help you re-evaluate your working thesis and determine whether you need to revise it. Remember that your working thesis was the starting point—not necessarily the end point—of your research. You should revise your working thesis if your ideas changed based on what you read. Even if your sources generally confirmed your preliminary thinking on the topic, it is still a good idea to tweak the wording of your thesis to incorporate the specific details you learned from research.

Below is a sample of a revised thesis statement from the example above:

Video source: https://youtu.be/27pa8_WAU_k

The metaphor is extraordinarily useful even though the passage is annoying. Beyond the sexist language of the time, I don’t appreciate the condescension toward “fact-collectors.” which reflects a general modernist tendency to elevate the abstract and denigrate the concrete. In reality, data-collection is a creative and demanding craft, arguably more important than theorizing. ↵