Chapter 4: Effective Study Habits

work smarter, not harder: effective studying techniques

Developing SMART Study Skills

At the beginning of the semester, your workload is relatively light. This is the perfect time to brush up on your study skills and establish good habits. When the demands on your time and energy become more intense, you will have a system in place for handling them. The goal of this section is to help you develop your own method for studying and learning efficiently.

As you work through this section, remember that every student is different. The strategies presented here are techniques that work well for many people; however, you may need to adapt them to develop a system that works well for you personally. If your friend swears by her smartphone, but you hate having to carry extra electronic gadgets around, then using a smartphone will not be the best organizational strategy for you.

Take a moment to consider what techniques have been effective (or ineffective) for you in the past. Which habits from your high school years or your work life could help you succeed now? Which habits might get in your way? What changes might you need to make?

Understanding Your Learning Preferences

To succeed in your post-secondary education—or any situation where you must master new concepts and skills—it helps to know what makes you tick. For decades, educational researchers and organizational psychologists have examined how people take in and assimilate new information, how some people learn differently than others, and what conditions make students and workers most productive. Here are just a few questions to think about:

- What times of day are you most productive? If your energy peaks early, you might benefit from blocking out early morning time for studying or writing. If you are a night owl, set aside a few evenings a week for schoolwork.

- How much clutter can you handle in your workspace? Some people work fine at a messy desk and know exactly where to find what they need in their stack of papers; however, most people benefit from maintaining a neat, organized space.

- How well do you juggle potential distractions in your environment? If you can study at home without being tempted to turn on the television, check your email, fix yourself a snack, and so on, you may make home your workspace. However, if you need a less distracting environment to stay focused, you may be able to find one on campus or in your community.

- Does a little background noise help or hinder your productivity? Some people work better when listening to background music or the low hum of conversation in a coffee shop. Others need total silence.

- When you work with a partner or group, do you stay on task? A study partner or group can sometimes be invaluable. However, working this way takes extra planning and effort, so be sure to use the time productively. If you find that group study sessions turn into social occasions, you may study better on your own.

- How do you manage stress? Accept that at certain points in the semester, you will feel stressed out. In your day-to-day routine, make time for activities that help you reduce stress, such as exercising, spending time with friends, or just scheduling downtime to relax

Video source: https://youtu.be/Bxv9lf5HjZM

Understanding your Learning Style

For the purposes of this chapter, learning style refers to the way you prefer to take in new information, by seeing, by listening, or through some other channel. (For more information, see the section on learning styles.)

Most people have one channel that works best for them when it comes to taking in new information. Knowing yours can help you develop strategies for studying, time management, and note taking that work especially well for you.

To begin identifying your learning style, think about how you would go about the process of assembling a piece of furniture. Which of these options sounds most like you?

- You would carefully look over the diagrams in the assembly manual first so you could picture each step in the process.

- You would silently read the directions through, step by step, and then look at the diagrams afterward.

- You would read the directions aloud under your breath. Having someone explain the steps to you would also help.

- You would start putting the pieces together and figure out the process through trial and error, consulting the directions as you worked.

Now read the following explanations of each option in the list above. Again, think about whether each description sounds like you.

- If you chose 1, you may be a visual learner. You understand ideas best when they are presented in a visual format, such as a flow chart, a diagram, or text with clear headings and many photos or illustrations.

- If you chose 2, you may be a verbal learner. You understand ideas best through reading and writing about them and taking detailed notes.

- If you chose 3, you may be an auditory learner. You understand ideas best through listening. You learn well from spoken lectures or books on tape.

- If you chose 4, you may be a kinesthetic learner. You learn best through doing and prefer hands-on activities. In long lectures, fidgeting may help you focus.

Learning Style Strategies

|

Learning Style |

Strategies |

| Visual | When possible, represent concepts visually—in charts, diagrams, or sketches.

Use a visual format for taking notes on reading assignments or lectures. Use different coloured highlighters or pens to colour code information as you read. Use visual organizers, such as maps and flow charts, to help you plan writing assignments. Use coloured pens, highlighters, or the review feature of your word processing program to revise and edit writing. |

| Verbal | Use the instructional features in course texts—summaries, chapter review questions, glossaries, and so on—to aid your studying.

Take notes on your reading assignments. Rewrite or condense reading notes and lecture notes to study. Summarize important ideas in your own words. Use informal writing techniques, such as brainstorming, freewriting, blogging, or posting on a class discussion forum to generate ideas for writing assignments. Reread and take notes on your writing to help you revise and edit. |

| Auditory | Ask your instructor’s permission to tape record lectures to supplement your notes.

Read parts of your textbook or notes aloud when you study. If possible, obtain an audiobook version of important course texts. Make use of supplemental audio materials, such as CDs or DVDs. Talk through your ideas with other students when studying or when preparing for a writing assignment. Read your writing aloud to help you draft, revise, and edit. |

| Kinesthetic | When you read or study, use techniques that will keep your hands in motion, such as highlighting or taking notes.

Use tactile study aids, such as flash cards or study guides you design yourself. Use self-stick notes to record ideas for writing. These notes can be physically reorganized easily to help you determine how to shape your paper. Use a physical activity, such as running or swimming, to help you break through writing blocks. Take breaks during studying to stand, stretch, or move around. |

Time Management

Getting Started: Short- and Long-Term Planning

At the beginning of the semester, establishing a daily/weekly routine for when you will study and write can be extremely beneficial. A general guideline is that for every hour spent in class, you should expect to spend another two to three hours on reading, writing, and studying for tests. Therefore, if you are taking a biology course that meets three times a week for an hour at a time, you can expect to spend six to nine hours per week on it outside of class. You will need to budget time for each class just like an employer schedules shifts at work, and you must make that study time a priority.

That may sound like a lot when taking several classes, but if you plan your time carefully, it is manageable. A typical full-time schedule of 15 credit hours translates into 30 to 45 hours per week spent on schoolwork outside of class. All in all, a full-time student would spend about as much time on school each week as an employee spends on work. Balancing school and a job can be more challenging, but still doable.

In addition to setting aside regular work periods, you will need to plan ahead to handle more intense demands, such as studying for exams and writing major papers. At the beginning of the semester, go through your course syllabi and mark all major due dates and exam dates on a calendar. Use a format that you check regularly, such as your smartphone or the calendar feature in your email. (In Section 1.3 Becoming a Successful Writer, you will learn strategies for planning major writing assignments so you can complete them on time.)

PRO TIP: The two- to three-hour rule may sound intimidating. However, keep in mind that this is only a rule of thumb. Realistically, some courses will be more challenging than others, and the demands will ebb and flow throughout the semester. You may have trouble-free weeks and stressful weeks. When you schedule your classes, try to balance introductory-level classes with more advanced classes so that your work load stays manageable.

Self-Practice Exercise

Now that you have learned some time management basics, it is time to apply those skills. For this exercise, you will develop a weekly schedule and a semester calendar.

- Working with your class schedule, map out a week-‐long schedule of study time. Try to apply the two to three-hour rule. Be sure to include any other nonnegotiable responsibilities, such as a job or child care duties.

- Use your course syllabi to record exam dates and due dates for major assignments in a calendar (paper or electronic). Use a star, highlighting, or other special marking to set off any days or weeks that look especially demanding.

Staying Consistent: Time Management Dos and Do Not’s

Setting up a schedule is easy. Sticking with it, however, may be challenging. A schedule that looked great on paper may prove to be unrealistic. Sometimes, despite students’ best intentions, they end up procrastinating or pulling all-nighters to finish a paper or study for an exam.

Keep in mind, however, that your weekly schedule and semester calendar are time management tools. Like any tool, their effectiveness depends on the user: you. If you leave a tool sitting in the box unused (e.g., you set up your schedule and then forget about it), it will not help you complete the task. And if, for some reason, a particular tool or strategy is not getting the job done, you need to figure out why and maybe try using something else.

With that in mind, read the list of time management dos and don’ts. Keep this list handy as a reference you can use throughout the semester to troubleshoot if you feel like your schoolwork is getting off track.

Do:

- Do set aside time to review your schedule and calendar regularly and update or adjust them as needed.

- Do be realistic when you schedule study time. Do not plan to write your paper on Friday night when everyone else is out socializing. When Friday comes, you might end up abandoning your plans and hanging out with your friends instead.

- Do be honest with yourself about where your time goes. Do not fritter away your study time on distractions like email and social networking sites.

- Do accept that occasionally your work may get a little off track. No one is perfect.

- Do accept that sometimes you may not have time for all the fun things you would like to do.

- Do recognize times when you feel overextended. Sometimes you may just need to get through an especially demanding week. However, if you feel exhausted and overworked all the time, you may need to scale back on some of your commitments.

- Do make a plan for handling high-stress periods, such as final exam week. Try to reduce your other commitments during those periods—for instance, by scheduling time off from your job. Build in some time for relaxing activities, too.

- Do be kind to yourself – many students balance school and other important responsibilities (work, family, friends, etc.). There will be times where you will have to prioritize where your time goes, and that’s okay.

Try Not To:

- Procrastinate on challenging assignments. Instead, break them into smaller, manageable tasks that can be accomplished one at a time. An assignment calculator can be a useful tool for helping to get yourself organized.

- Fall into the trap of “all or nothing” thinking. (e.g. “There is no way I can fit in a three-hour study session today, so I will just wait until the weekend.”) Extended periods of free time are hard to come by, so find ways to use small blocks of time productively. For instance, if you have a free half hour between classes, use it to preview a chapter or brainstorm ideas for an essay.

One of the best things you can do for yourself as a student is realize that we all procrastinate at some point. Knowing your procrastination style can help you to recognize and change bad habits. Look at the chart below and see if you can identify your procrastination style (you might use more than one!):

| Type of Procrastinator | Bad Habits | Strategies |

| Perfectionist | Reluctant to start work because of fears that it will never be good enough | Leave enough time to do multiple drafts of your work. Put you assignment down for a few days, then come back to it and edit/revise.

Remind yourself that you’re in school because you are learning and that no one expect perfection. |

| Productive | Is very productive with work… but they aren’t doing the work that they should be doing. (Ex. cleaning the apartment instead of studying) | Ask yourself why you’re focused on other things right now. Maybe you’ve been studying too long and need a break? Maybe you don’t understand the assignment and need clarification? |

| Good Samaritan | Finds things to do for other people to put off doing their own work (Ex. helping a friend study for their test) | Let friends/family know that you have an upcoming deadline so that they know you are unavailable. |

| Saboteur | Puts themself into situations where they know they will be distracted or unsuccessful (Ex. studying in a living room) | Create or find a study space that you reserve just for doing your work. As much as possible, it should be isolated and have all of your study materials at-hand. |

| Dreamer | Has too many ideas and finds it difficult to settle on just one. | Brainstorm a list of your ideas and then compare it to the assignment. Which idea fits the best with what you’re being asked to do? |

| Ostrich | Gets overwhelmed with the amount of work/assignments and shuts down (Ex. end up playing video games to avoid the situation entirely) | Create a list of everything that you have to do for each class, then put all of the dates into a calendar so that you can see what needs to be prioritized. Breaking up big tasks can make things more manageable. |

| Daredevil | Does best under the pressure of doing work at the last minute. (Ex. studies for tests the night before or morning of the exam) | Move your deadlines ahead in your calendar to give yourself a few days as a buffer.

Set micro goals with a time limit and see if you can beat the clock. Go back and edit/revise once you’re finished. Have someone quiz you on your material after a timed study session. |

| Distracted | Ends up getting distracted by other things (Ex. begins researching vaccines and spends hours reading about conspiracy theories) | Set a timer to “check in” on your progress. Are you finding yourself distracted? Keep a list beside you of things you need or want to do once you’re finished studying.

Keep your cellphone out of your study area. Use online tools that lock down your social media sites for certain lengths of time. Use a reward system (Ex. Finish this chapter and then one episode on Netflix). |

Self-Practice Exercise

The key to managing your time effectively is consistency. Completing the following tasks will help you stay on track throughout the semester.

- Establish regular times to “check in” with yourself to identify and prioritize tasks and plan how to accomplish them. Many people find it is best to set aside a few minutes for this each day and to take some time to plan at the beginning of each week.

- For the next two weeks, focus on consistently using whatever time management system you have set up. Check in with yourself daily and weekly, stick to your schedule, and take note of anything that interferes. At the end of the two weeks, review your schedule and determine whether you need to adjust it.

studying & Note-Taking Methods

Summarizing is one of the most effective means of studying and making sure that you’ve learned the concept/skill. Can you go through the steps mentally? Can you describe or explain it to someone else in your own words? This is the process of summarizing and synthesizing information.

When summarizing material from a source, you zero in on the main points and restate them concisely in your own words. This technique is appropriate when only the major ideas are relevant to your paper or when you need to simplify complex information into a few key points for your readers. To create a summary, consider the following points:

- Review the source material as you summarize it.

- Identify the main idea and restate it as concisely as you can—preferably in one sentence. Depending on your purpose, you may also add another sentence or two condensing any important details or examples.

- Check your summary to make sure it is accurate and complete.

- Make a careful record of where you found the information because you will need to include the reference and citation if you choose to use the information in an essay. It is much easier to do this when you are creating the summary and taking notes than having to go back and hunt for the information later. Guessing where you think you got it from is not good enough.

Summaries and Abstracts

When you read many academic journal articles, you will notice there is an abstract before the article starts: this is a summary of the article’s contents. Be careful when you are summarizing an article to not depend too much on the abstract as it is already a condensed version of the content. The author of the abstract identified the main points from his or her perspective; these may not match your own purpose or your own idea of what is important. What may also happen if you try to summarize the abstract is you will probably end up replacing some words with synonyms and not changing the overall ideas into your own words because the ideas are already summarized, and it is difficult to make them more generalized. You have to read the entire source or section of the source and determine for yourself what the key and supporting ideas are.

PRO TIP: A summary or abstract of a reading passage is one-tenth to one-quarter the length of the original passage, written in your own words. The criteria for a summary are that it:

- Is similar to an outline but in complete sentences and can stand as an independent piece of writing

- Includes only the main points and key details

- Is valuable because it is the surest way to measure your understanding

- Helps you remember because you must attend carefully to what you read, organize your thoughts, and write them out to make it meaningful to you (This is absolutely necessary when you cannot mark a book because it belongs to someone else.)

- Challenges you to be concise in your writing while providing balanced coverage of the main points.

- Challenges you to paraphrase or use your own words and avoid using too many quotations.

- Is important to remain objective because you are giving the author’s views not your own.

Example

Article: Assessing the Efficacy of Low–Carbohydrate Diets

Adrienne Howell, Ph.D. (2010)

Over the past few years, a number of clinical studies have explored whether high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets are more effective for weight loss than other frequently recommended diet plans, such as diets that drastically curtail fat intake (Pritikin) or that emphasize consuming lean meats, grains, vegetables, and a moderate amount of unsaturated fats (the Mediterranean diet). A 2009 study found that obese teenagers who followed a low-carbohydrate diet lost an average of 15.6 kilograms over a six-month period, whereas teenagers following a low-fat diet or a Mediterranean diet lost an average of 11.1 kilograms and 9.3 kilograms respectively. Two 2010 studies that measured weight loss for obese adults following these same three diet plans found similar results. Over three months, subjects on the low-carbohydrate diet plan lost anywhere from four to six kilograms more than subjects who followed other diet plans.

Summary

In three recent studies, researchers compared outcomes for obese subjects who followed either a low-carbohydrate diet, a low-fat diet, or a Mediterranean diet and found that subjects following a low-carbohydrate diet lost more weight in the same time (Howell, 2010).

What Is aNNOTATION?

Most students already know how to annotate. When you make notes in the margins and highlight your textbooks, you are annotating that source.

When you take notes in the margins of your readings, highlight key ideas, underline passages, etc, you are annotating a source. Annotations are a valuable research tool because they allow you to capture your first ideas and impressions of a text, as well as enable you to find key information again quickly without having to re-read the entire text.

When annotating, you should be looking for several things:

- Key ideas, terms, and concepts

- Words or concepts that you don’t understand yet

- Points that are being made with which you (dis)agree

- Pieces of evidence that would be useful for your own paper

- Inconsistent information with what you have read elsewhere

- Parts of the text you may wish to return to later in the research process

PRO TIP: LEARN TO USE YOUR HIGHLIGHTER PROPERLY!

Many students – if not most – do not use highlighters effectively. Highlighting is a visual cue that is intended to help you recall or find information quickly. If you are the person who highlights 3/4 of the page or chapter, you are not using the tool effectively.

When studying, you should have multiple colours of highlighter with you and designate certain colours for certain things. For example:

DEFINITIONS

MAIN IDEAS

UNCLEAR CONCEPTS

KEY EVIDENCE OR POINTS

This strategy has a few benefits:

- It forces you to slow down to switch colours, giving you more time to process what you’re reading

- It makes you read actively in order to determine how the information should be classified (for example: is this a definition or a main idea?)

- It creates a study system for you that is consistent and easier to follow

Video source: https://youtu.be/eVajQPuRmk8

Self-Practice Exercise

- Read the following passage and use a note-‐taking method to identify the main points.

- Compose a sentence summarizing the paragraph’s main points.

Several factors about the environment influence our behaviour. First, temperature can influence us greatly. We seem to feel best when the temperature is in the high teens to low 20s. If it is too hot or cold, we have trouble concentrating. Lighting also influences how we function. A dark lecture hall may interfere with the lecture, or a bright nightclub might spoil romantic conversation. Finally, our behaviour is affected by colour. Some colours make us feel a peaceful while others are exciting. If you wanted a quiet room in which to study, for example, you would not paint it bright orange or red.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Here are possible answers:

Key points:

Environmental factors influence behaviour:

- Temperature: extremes make focus difficult

- Lighting: inappropriate lighting is disorientating

- Colour: colour affects relaxation

Summary sentence: Three environmental influences that impact human behaviour include temperature, as extreme fluctuations make it difficult to focus; lighting, which can affect our ability to engage with different environments; and colour, which affects our mood.

Passage taken from: Ueland, B. (2006). Becoming a Master Student. Boston, MA : Houghton Mifflin College Div., p. 121.

Self-Practice Exercise

- Read the passage.

- Highlight or underline necessary information (hint: there are five important ideas).

- Write your summary.

Most people drink orange juice and eat oranges because they are said to be rich in vitamin C. There are also other foods that are rich in vitamin C. It is found in citrus fruits and vegetables such as broccoli, spinach, cabbage, cauliflower, and carrots.

Vitamin C is important to our health. Do you really know how essential this nutrient is to our health and well-being? Our body needs to heal itself. Vitamin C can repair and prevent damage to the cells in our body and heal wounds. It also keeps our teeth and gums healthy. That is not all. It protects our body from infections such as colds and flu and also helps us to get better faster when we have these infections. That is why a lot of people drink orange juice and take vitamin C tablets every day. This wonderful vitamin is also good for our heart. It protects the linings of the arteries, which are the blood vessels that carry oxygenated blood. In other words, it offers protection against heart disease.

If we do not get enough vitamin C, which means we are not eating enough food that contains this vitamin, it can lead to serious diseases. Lack of vitamin C can lead to scurvy, which causes swollen gums, cheeks, fingers, hands, toes, and feet. In serious conditions, it can lead to bleeding from wounds, loss of teeth, and opening up of wounds. Therefore, make sure you have enough vitamin C in your diet.

Collaboration: Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Exercise taken from: http://www.scribd.com/doc/98238709/Form-‐Three-‐Summary-‐Writing-‐Exercise

Annotating, note making, or note taking is a matter of personal preference in terms of style. The most important thing is to do something. Again we stress that reading is like a dialogue with an author. The author wrote this material. Pretend you are actually talking to the author.

- Do not let an idea pass without noting it.

- Do not let an ambiguity go by without questioning it.

- Do not let a term slip away if context does not help you understand it; look it up!

- Engage and you will both understand and remember.

PRO TIP: Put small checks in pencil where you would normally underline. When you finish a section, look back and see what you really need to mark. (If you check over 50 percent of the page, you probably are marking to go back and learn later versus thinking about what is really important to learn now!)

Use consistent symbols to visually help you identify what is happening on the page:

- Circle central themes or write at the beginning of the section if it is not directly stated.

- [Bracket] main points.

- Underline key words or phrases for significant details.

- Put numbers 1, 2, 3 for items listed.

- Put square brackets or highlights for key terms when the definition follows.

- Use stars (*), question marks (?), or diagrams in the margins to show relevance.

- Use key word outlines in the margins for highlighting.

- Write questions in the margin that test your memory of what is written right there.

- Use blank spaces indicating the number of ideas to be remembered, forcing you to test yourself versus just rereading.

General Note-Taking Guidelines

- Before class, quickly review your notes from the previous class and the assigned reading. Fixing key terms and concepts in your mind will help you stay focused and pick out the important points during the lecture.

- Come prepared with paper, pens, highlighters, textbooks, and any important handouts.

- Come to class with a positive attitude and a readiness to learn. During class, make a point of concentrating. Ask questions if you need to. Be an active participant.

- During class, capture important ideas as concisely as you can. Use words or phrases instead of full sentences, and abbreviate when possible.

- Visually organize your notes into main topics, subtopics, and supporting points, and show the relationships between ideas. Leave space if necessary so you can add more details under important topics or subtopics.

- If your professor gives you permission to do so, you could consider taking pictures of the notes on the board with a mobile device or audio recording the lecture.

- Record the following:

- Ideas that the instructor repeats frequently or points out as key ideas

- Ideas the instructor lists on a whiteboard or transparency

- Details, facts, explanations, and lists that develop main points

- Review your notes regularly throughout the semester, not just before exams.

Organizing Ideas in Your Notes

A good note-taking system needs to help you differentiate among major points, related subtopics, and supporting details. It visually represents the connections between ideas. Finally, to be effective, your note-taking system must allow you to record and organize information fairly quickly. Although some students like to create detailed, formal outlines or concept maps when they read, these may not be good strategies for class notes because spoken lectures may not allow time for to create them.

Instead, focus on recording content simply and quickly to create organized, legible notes. Try one of the following techniques.

Modified Outline Format

A modified outline format uses indented spacing to show the hierarchy of ideas without including roman numerals, lettering, and so forth. Just use a dash or bullet to signify each new point unless your instructor specifically presents a numbered list of items.

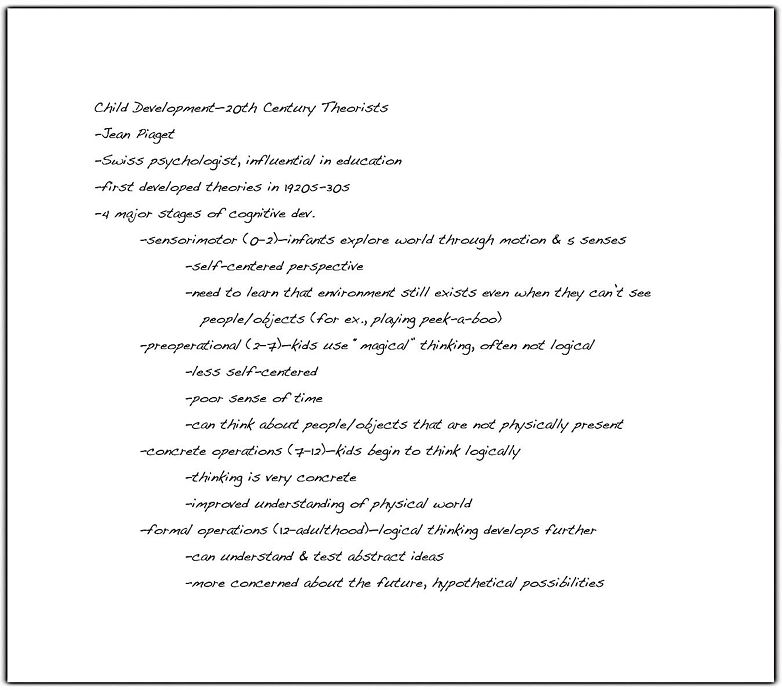

The first example shows Crystal’s notes from a developmental psychology class about an important theorist in this field. Notice how the line for the main topic is all the way to the left. Subtopics are indented, and supporting details are indented one level further. Crystal also used abbreviations for terms like development and example.

Mind Mapping/Clustering

Mind Mapping/Clustering

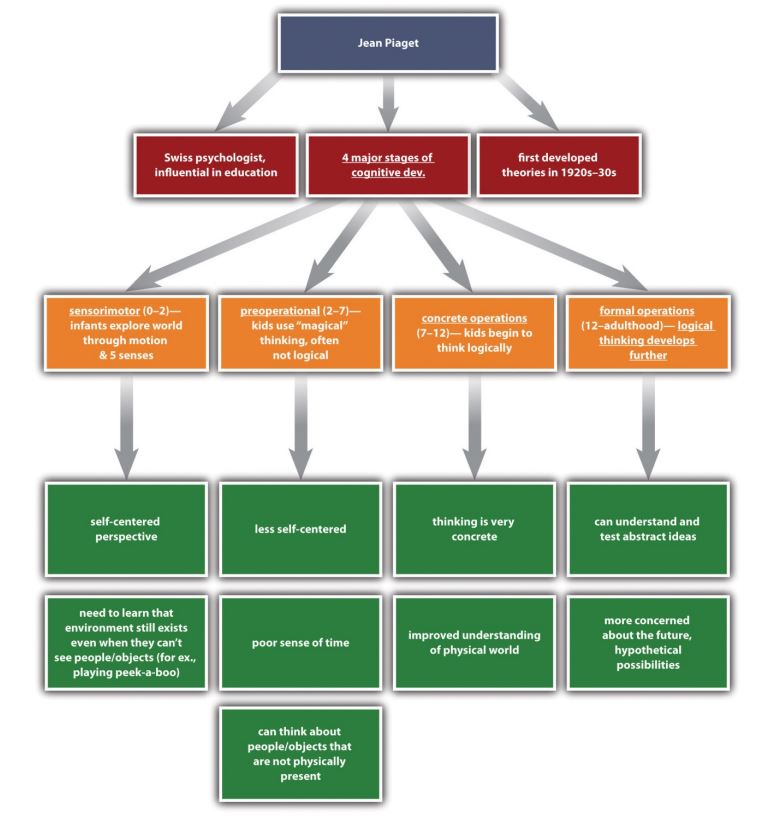

If you are a visual learner, you may prefer to use a more graphic format for notes, such as a mind map. The next example shows how Crystal’s lecture notes could be set up differently. Although the format is different, the content and organization are the same.

Child Development – 20th Century Theorists

Charting

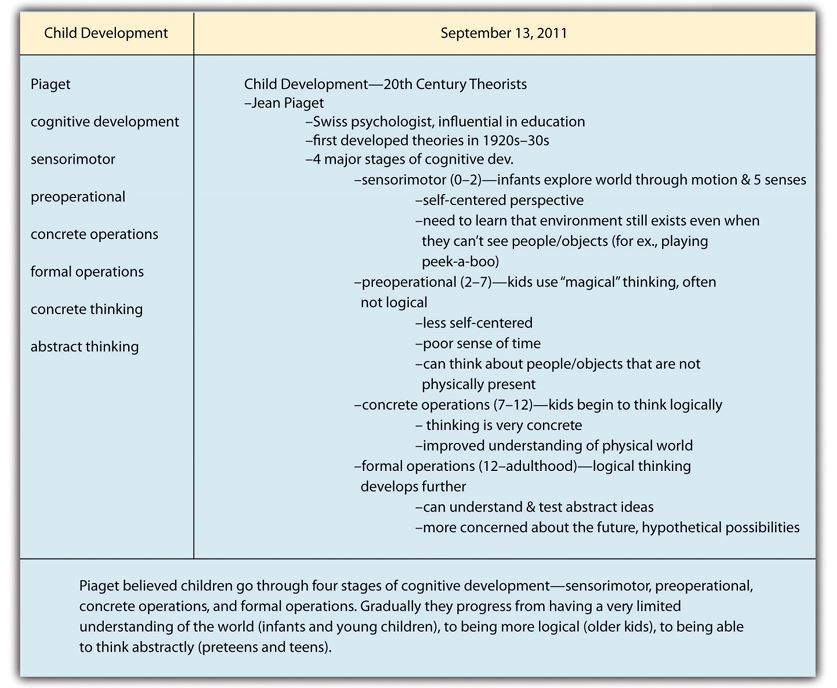

Charting

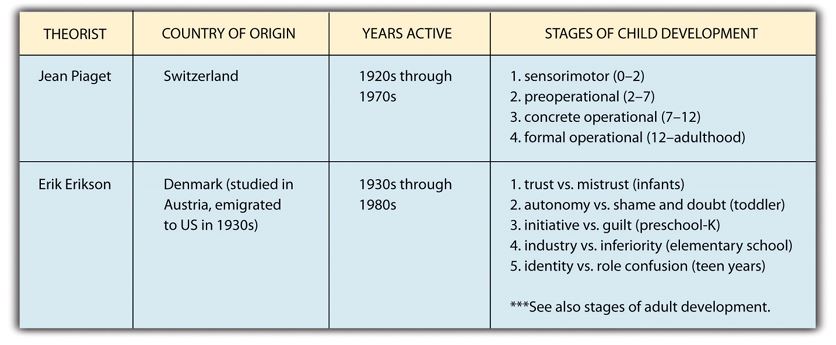

If the content of a lecture falls into a predictable, well organized pattern, you might choose to use a chart or table to record your notes. This system works best when you already know, either before class or at the beginning of class, which categories you should include. The next figure shows how this system might be used.

The Cornell Note-Taking System

In addition to the general techniques already described, you might find it useful to practise a specific strategy known as the Cornell note-taking system. This popular format makes it easy not only to organize information clearly but also to note key terms and summarize content.

To use the Cornell system, begin by setting up the page with these components:

- The course name and lecture date at the top of the page

- A narrow column (about two inches) at the left side of the page

- A wide column (about five to six inches) on the right side of the page

- A space of a few lines marked off at the bottom of the page

During the lecture, you record notes in the wide column. You can do so using the traditional modified outline format or a more visual format if you prefer.

Then, as soon as possible after the lecture, review your notes and identify key terms. Jot these down in the narrow left-hand column. You can use this column as a study aid by covering the notes on the right-hand side, reviewing the key terms, and trying to recall as much as you can about them so that you can mentally restate the main points of the lecture. Uncover the notes on the right to check your understanding. Finally, use the space at the bottom of the page to summarize each page of notes in a few sentences.

Self-Practice Exercise

Over the next few weeks, establish a note-‐taking system that works for you.

- If you are not already doing so, try using one of the aforementioned techniques. (Remember that the Cornell system can be combined with other note-‐taking formats.)

- It can take some trial and error to find a note-‐taking system that works for you. If you find that you are struggling to keep up with lectures, consider whether you need to switch to a different format or be more careful about distinguishing key concepts from unimportant details.

- If you find that you are having trouble taking notes effectively, set up an appointment with your school’s academic resource centre.

Using Online Study Tools

1. Guided Study Session Videos

One excellent tool to help with accountability is guided study session videos. Much like guided meditation, these videos can help you stay on track and give you some accountability. It’s like a study partner that can’t distract you!

Video source: https://youtu.be/reRYtjr1BNo

2. The Pomodoro Technique

Much like a Guided Study Session, the Pomodoro Study Session plays ambient noise and displays a timer. Every 25 minutes, you take a break from whatever you’re doing. During this time you can stretch, check your phone, etc. Here’s a neat Harry Potter themed one!

Video source: https://youtu.be/SkmH9CsMqOo

3. Browser Lockdown Tools

Are you the person who is always getting distracted while studying? You might consider a website blocker (list of some available here) that will prohibit you from accessing certain sites for a certain length of time. You tell it your guilty procrastination sites (Reddit? Instagram? Discord?) and how long you want them locked.

And maybe leave your phone/tablet in another room… 😏

4. Find a Notetaking Program/System

There are a variety of free notetaking systems and programs available. Many students prefer the ease of a program like Google Docs, but there are others such as Evernote, and OneNote.

5. Looking into Assistive Technology

Assistive technology has been used by students with disabilities for a long time; however, these tools are equally valuable for all students! Not all of them are free, but they can be a game changer for some people:

Digital Highlighters: these cool gadgets allow you to scan hardcopy texts with a pen and it will transfer the text into a digital format on your computer/tablet. Some popular options are Scanmarker and IrisPen

Text-to-Speech Pens/Reader Pens: Similar to digital highlighters, these pens also have the ability to read the text that you scan out loud. Some of them also feature dictionaries built into the pen. They are often a tool of choice for students who are learning English as an additional language and for those with dyslexia, AD(H)D, etc. The most popular option is the C-Pen

Digital Notebooks and Smart Pens: Digital notebooks are an excellent hybrid of physical note taking with technological storage. One of the more popular options is the Rocektbook, which is reusable and allows you to write notes and scan them to a notetaking program using a phone app. Smart Pens, like the LiveScribe Pen allow you to record audio, take pictures, and transfer handwritten notes to a note taking program.

Text-to-Speech Readers: this type of technology has become more popular in recent years. These programs read digital texts aloud to you, and many are available online for free, but you may wish to start with one like NaturalReader to see if it’s helpful.

Speech-to-Text Programs: the opposite of a text-to-speech reader and exactly what it sounds like, Speech-to-Text programs allow you to dictate to the computer using a microphone and what you say will be converted into text. This website has a list of popular free programs, broken down by OS.

Using Available ACADEMIC Support Resources

One reason students sometimes find post-secondary courses overwhelming is that they do not know about, or are reluctant to use, the resources available to them. There is help available; your student fees help pay for resources that can help in many ways, such as a health centre or tutoring service. If you need help, consider asking for help from any of the following:

- Your instructor: If you are making an honest effort but still struggling with a particular course, set a time to meet with your instructor and discuss what you can do to improve. He or she may be able to shed light on a confusing concept or give you strategies to catch up.

- Your academic advisor or program coordinator: Many institutions assign students an academic advisor or program coordinator who can help you choose courses and ensure that you fulfill degree and major requirements.

- The academic resource centre: These centres offer a variety of services, which may range from general coaching in study skills to tutoring for specific courses. Find out what is offered at your school and use the services that you need.

- The writing centre (Sheridan Tutoring Services): These centres employ tutors to help you manage your writing assignments. They will not write or edit your paper for you, but they can help you through the stages of the writing process. (In some schools, the writing centre is part of the academic resource centre.)

- The career resource centre: Visit the career resource centre for guidance in choosing a career path, developing a resumé, and finding and applying for jobs.

- Sheridan Counselling services: Sheridan offers counselling services on campus for free. Use these services if you need help coping with a difficult personal situation or managing depression, anxiety, or other problems.

Students sometimes neglect to use available resources due to limited time, unwillingness to admit there is a problem, or embarrassment about needing to ask for help. Unfortunately, ignoring a problem usually makes it harder to cope with later on. Waiting until the end of the semester may also mean fewer resources are available, since many other students are also seeking last minute help.

Self-Practice Exercise