2. Legal Risk Management

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Processes for Mitigating Risk

Negotiation

We frequently engage in negotiations as we go about our daily activities, often without being consciously aware that we are doing so. Negotiation can be simple, e.g., two friends deciding on a place to eat dinner, or complex, e.g., governments of several nations trying to establish import and export quotas across multiple industries. When a formal proceeding is started in the court system, alternative dispute resolution (ADR), or ways of solving an issue with the intent to avoid litigation, may be employed. Negotiation is often the first step used in ADR. While there are other forms of alternative dispute resolution, negotiation is considered to be the simplest because it does not require outside parties. A Government of Canada webpage defines ‘negotiation” as: “…a discussion between at least two parties that leads to an outcome of a certain issue.” (https://www.canada.ca/en/heritage-information-network/services/intellectual-property-copyright/guide-developing-digital-licensing-agreement-strategy/win-win-negotiations.html)

This is an uncomplicated definition that captures a fundamental feature of negotiation – it is undertaken with an intention to lead to an outcome. There are several ways of thinking about negotiation, including how many parties are involved. For example, if two small business owners find themselves in a disagreement over property lines, they will frequently engage in dyadic negotiation. Put simply, dyadic negotiation involves two individuals interacting with one another to resolve a dispute. If a third neighbour overhears the dispute and believes one or both of them are wrong about the property line, then group negotiation could ensue. Group negotiation involves more than two individuals or parties, and by its very nature, it is often more complex, time-consuming, and challenging to resolve.

While dyadic and group negotiations may involve different dynamics, one of the most important aspects of any negotiation, regardless of the quantity of negotiators, is the objective. Negotiation experts recognize two major goals of negotiation: relational and outcome. Relational goals are focused on building, maintaining, or repairing a partnership, connection, or rapport with another party. Outcome goals, on the other hand, concentrate on achieving certain end results. The goal of any negotiation is influenced by numerous factors, such as whether there will be contact with the other party in the future. For example, when a business negotiates with a supply company that it intends to do business within the near future, it will try to focus on “win-win” solutions that provide the most value for each party. In contrast, if an interaction is of a one-time nature, that same company might approach a supplier with a “win-lose” mentality, viewing its objective as maximizing its own value at the expense of the other party’s value. This approach is referred to as zero-sum negotiation, and it is considered to be a “hard” negotiating style. Zero-sum negotiation is based on the notion that there is a “fixed pie,” and the larger the slice that one party receives, the smaller the slice the other party will receive. Win-win approaches to negotiation are sometimes referred to as integrative, while win-lose approaches are called distributive.

Negotiation Style

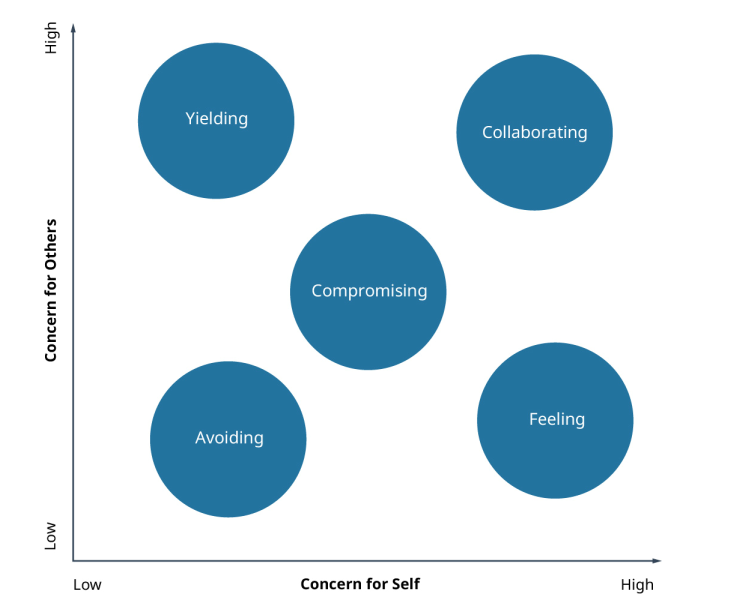

Everyone has a different way of approaching negotiation, depending on the circumstance and the person’s personality. However, the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) is a questionnaire that provides a systematic framework for categorizing five broad negotiation styles. It is closely associated with work done by conflict resolution experts Dean Pruitt and Jeffrey Rubin. These styles are often considered in terms of the level of self-interest, instead of how other negotiators feel. These five general negotiation styles include:

- Forcing. If a party has high concern for itself, and low concern for the other party, it may adopt a competitive approach that only takes into account the outcomes it desires. This negotiation style is most prone to zero-sum thinking. For example, a car dealership that tries to give each customer as little as possible for his or her trade-in vehicle would be applying a forcing negotiation approach.

While the party using the forcing approach is only considering its own self-interests, this negotiating style often undermines the party’s long-term success. For example, in the car dealership example, if a customer feels she has not received a fair trade-in value after the sale, she may leave negative reviews and will not refer her friends and family to that dealership and will not return to it when the time comes to buy another car.

- Collaborating. If a party has high concern and care for both itself and the other party, it will often employ a collaborative negotiation that seeks to maximum the gain for both. In this negotiating style, parties recognize that acting in their mutual interests may create greater value and synergies.

- Compromising. A compromising approach to negotiation will take place when parties share some concerns for both themselves and the other party. While it is not always possible to collaborate, parties can often find certain points that are more important to one versus the other, and in that way, find ways to isolate what is most important to each party.

- Avoiding. When a party has low concern for itself and for the other party, it will often try to avoid negotiation completely.

- Yielding. Finally, when a party has low self-concern for itself and high concern for the other party, it will yield to demands that may not be in its own best interest. As with avoidance techniques, it is important to ask why the party has low self-concern. It may be due to an unfair power differential between the two parties that has caused the weaker party to feel it is futile to represent its own interests. This example illustrates why negotiation is often fraught with ethical issues.

Negotiation Limitations

In a negotiation, there is no neutral third party to ensure that rules are followed, that the negotiation strategy is fair (the parties involved may have unequal bargaining power), or that the overall outcome is sound. Moreover, any party can walk away whenever it wishes. There is no guarantee of realizing an intended outcome.

Mediation

Mediation is a method of dispute resolution that relies on an impartial third-party decision-maker, known as a mediator, to settle a dispute. While requirements vary by location or jurisdiction, a mediator is someone who has been trained in conflict resolution, though, he or she may not have any expertise in the subject matter that is being disputed. Mediation is a form of dispute resolution. It is often undertaken because it can help disagreeing parties avoid the time-consuming and expensive procedures involved in court litigation. Courts will often recommend that a plaintiff, or the party initiating a lawsuit, and a defendant, or the party that is accused of wrongdoing, attempt mediation before proceeding to trial. This recommendation is especially true for issues that are filed in small claims courts, where judges attempt to streamline dispute resolution.

For businesses, the savings associated with mediation can be substantial. Mediation is distinguished by its focus on solutions. Instead of focusing on discoveries, testimonies, and expert witnesses to assess what has happened in the past, it is future-oriented. Mediators focus on generating approaches to disputes that overcome obstacles to settlement.

Benefits of Mediation

- Confidentiality. Since court proceedings become a matter of public record, it can be advantageous to use mediation to preserve anonymity. This aspect can be especially important when dealing with sensitive matters, where one or both parties feels it is best to keep the situation private. Discussions during a mediation are not admissible as evidence if the parties proceed to litigation.

- Creativity. Mediators are trained to find ways to resolve disputes and may apply outside-the-box thinking to suggest a resolution that the parties had not considered. Since disagreeing parties can be feeling emotionally contentious toward one another, they may not be able to consider other solutions. In addition, a skilled mediator may be able to recognize cultural differences between the parties that are influencing the parties’ ability to reach a compromise, and thus leverage this awareness to create a novel solution.

- Control. When a case goes to trial, both parties give up a certain degree of control over the outcome. A judge may come up with a solution to which neither party is in favor. In contrast, mediation gives the disputing parties opportunities to find common ground on their own terms, before relinquishing control to outside forces. Parties often enter into a legally binding contract that embodies the terms of the resolution immediately after a successful mediation. Therefore, the terms of the mediation can become binding if they are reduced to a contract.

Successful mediators work to immediately establish personal rapport with the disputing parties. They often have a short period of time to interact with the parties and work to position themselves as a trustworthy facilitator. The mediator’s conflict resolution skills are critical in guiding the parties toward reaching a resolution.

Arbitration

According to the Government of Canada “Dispute Resolution Reference Guide”: “Arbitration is perhaps the most widely known dispute resolution process. Like litigation, arbitration utilizes an adversarial approach that requires a neutral party to render a decision.” (https://justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/dprs-sprd/res/drrg-mrrc/06.html).

Arbitration is overseen by a neutral arbitrator, or an individual who is responsible for deciding on how to resolve a dispute and who can decide on an award, or a course of action that the arbiter believes is fair, given the situation. An award can be a monetary payment that one party must pay to the other; however, awards need not always be financial in nature. An award may require that one business stop engaging in a certain practice that is deemed unfair to the other business. As distinguished from mediation, in which the mediator simply serves as a facilitator who is attempting to help the disagreeing parties reach an agreement, and arbitrator acts more like a judge in a court trial and often has legal expertise, although he or she may or may not have subject matter expertise. Many arbitrators are current or retired lawyers and judges.

Types of Arbitration Agreements

Parties can enter into either voluntary or involuntary arbitration. In voluntary arbitration, the disputing parties have decided, of their own accord, to seek arbitration as a way to potentially settle their dispute. Depending on provincial laws (each province and territory in Canada has its own separate arbitration legislation) and the nature of the dispute, disagreeing parties may have to attempt arbitration before resorting to litigation; this requirement is known as involuntary arbitration because it is forced upon them by an outside party.

Arbitration can be either binding or non-binding. In binding arbitration, the decision of the arbitrator(s) is final, and except in rare circumstances, neither party can appeal the decision through the court system. In non-binding arbitration, the arbitrator’s award can be thought of as a recommendation; it is only finalized if both parties agree that it is an acceptable solution. Having a neutral party assess the situation may help disputants to rethink and reassess their positions and reach a future compromise.

Issues Covered by Arbitration Agreements

There are many instances in which arbitration agreements may prove helpful as a form of alternative dispute resolution. While arbitration can be useful for resolving family law matters, such as divorce, custody, and child support issues, in the domain of business law, it has three major applications:

- Labour. Arbitration has often been used to resolve labour disputes through interest arbitration and grievance arbitration. Interest arbitration addresses disagreements about the terms to be included in a new contract, e.g., workers of a union want their break time increased from 15 to 25 minutes. In contrast, grievance arbitration covers disputes about the implementation of existing agreements. In the example previously given, if the workers felt they were being forced to work through their 15-minute break, they might engage in this type of arbitration to resolve the matter.

- Business Transactions. Whenever two parties conduct business transactions, there is potential for misunderstandings and mistakes. Both business-to-business transactions and business-to-consumer transactions can potentially be solved through arbitration. Any individual or business who is unhappy with a business transaction can attempt arbitration.

- Property Disputes. Business can have various types of property disputes. These might include

- disagreements over physical property, e.g., deciding where one property ends and another begins, or intellectual property, e.g., trade secrets, inventions, and artistic works.

- Typically, civil disputes, as opposed to criminal matters, attempt to use arbitration as a means of dispute resolution. While definitions can vary across jurisdictions, a civil matter is generally one that is brought when one party has a grievance against another party and seeks monetary damages. In contrast, in a criminal matter, a government pursues an individual or group for violating laws meant to establish the best interests of the public.

Ethics of Commercial Arbitration Clauses

Going to court to solve a dispute is a costly endeavour, and for large companies, it is possible to incur millions of dollars in legal expenses. While arbitration is meant to be a form of dispute resolution that helps disagreeing parties find a low-cost, time-efficient solution, it has become increasingly important to question whose expenses are being lowered, and to what effect. Many consumer advocates are fighting against what are known as forced-arbitration clauses, in which consumers agree to settle all disputes through arbitration, effectively waiving their right to sue a company in court. Some of these forced arbitration clauses cause the other party to forfeit their right to appeal an arbitration decision or participate in any kind of class action lawsuit, in which individuals who have a similar issue sue as one collective group.

Arbitration Procedures

When parties enter into arbitration, certain procedures are followed although not all arbitration agreements have the same procedures. It depends on the types of agreements made in advance by the disputing parties. Typically, the initial step identifies the number of arbitrators needed, along with how they will be chosen. Parties that enter into willing arbitration may have more control over this decision, while those that do so unwillingly may have a limited pool of arbitrators from which to choose. In the case of willing arbitration, parties may decide to have three arbitrators, one chosen by each of the disputants and the third chosen by the elected arbitrators. Next, a timeline is established, and evidence is presented by both parties. Since arbitration is less formal than court proceedings, the evidence phase typically goes faster than it would in a courtroom setting. Finally, the arbitrator will decide and inform the parties in writing of the award.

Judicial Enforcement of Arbitration Awards

While it might seem that the party that is awarded a settlement by an arbitrator has reason to be relieved that the matter is resolved, sometimes this decision represents just one more step toward actually receiving the award. While a party may honor the award and voluntarily comply, this outcome is not always the case. In cases where the other party does not comply, the next step is to petition the court to enforce the arbitrator’s decision. This task can be accomplished by numerous mechanisms, depending on the governing laws.