37 Making Competitive Moves

Learning Objectives

- Understand the advantages and disadvantages of being a first mover.

- Know how disruptive innovations can change industries.

- Describe two ways that using foothold can benefit firms.

- Explain how firms can win without fighting using a blue ocean strategy.

- Describe the creative process of bricolage.

Being a First Mover: Advantages and Disadvantages

A famous cliché contends that “the early bird gets the worm.” Applied to the business world, the cliché suggests that certain benefits are available to a first mover[1] into a market that will not be available to later entrants (Figure 6.2 “Making Competitive Moves”).

A first-mover advantage[2] exists when making the initial move into a market allows a firm to establish a dominant position that other firms struggle to overcome (Figure 6.3 “First Mover Advantage”). For example, Apple’s creation of a user-friendly, small computer in the early 1980s helped fuel a reputation for creativity and innovation that persists today. Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) was able to develop a strong bond with Chinese officials by being the first Western restaurant chain to enter China. Today, KFC is the leading Western fast-food chain in this rapidly growing market. Genentech’s early development of biotechnology allowed it to overcome many of the pharmaceutical industry’s traditional entry barriers (such as financial capital and distribution networks) and become a profitable firm. Decisions to be first movers helped all three firms to be successful in their respective industries (Ketchen, Snow, & Street, 2004).

On the other hand, a first mover cannot be sure that customers will embrace its offering, making a first move inherently risky. Apple’s attempt to pioneer the personal digital assistant market, through its Newton, was a financial disaster. The first mover also bears the costs of developing the product and educating customers. Others may learn from the first mover’s successes and failures, allowing them to cheaply copy or improve the product. In creating the Palm Pilot, for example, 3Com was able to build on Apple’s earlier mistakes. Matsushita often refines consumer electronic products, such as compact disc players and projection televisions, after Sony or another first mover establishes demand. In many industries, knowledge diffusion and public-information requirements make such imitation increasingly easy.

One caution is that first movers must be willing to commit sufficient resources to follow through on their pioneering efforts. RCA and Westinghouse were the first firms to develop active-matrix LCD display technology, but their executives did not provide the resources needed to sustain the products spawned by this technology. Today, these firms are not even players in this important business segment that supplies screens for notebook computers, phones, medical instruments, and many other products.

To date, the evidence is mixed regarding whether being a first mover leads to success. One research study of 1,226 businesses over a fifty-five-year period found that first movers typically enjoy an advantage over rivals for about a decade, but other studies have suggested that first moving offers little or no advantages.

Perhaps the best question that executives can ask themselves when deciding whether to be a first mover is, how likely is this move to provide my firm with a sustainable competitive advantage? First moves that build on strategic resources such as patented technology are difficult for rivals to imitate and thus are likely to succeed. For example, Pfizer enjoyed a monopoly in the erectile dysfunction market for five years with its patented drug Viagra before two rival products (Cialis and Levitra) were developed by other pharmaceutical firms. Despite facing stiff competition, Viagra continues to raise about $1.9 billion in sales for Pfizer annually. (Figures from Standard & Poor’s stock report on Pfizer.)

In contrast, E-Trade Group’s creation in 2003 of the portable mortgage seemed doomed to fail because it did not leverage strategic resources. This innovation allowed customers to keep an existing mortgage when they move to a new home. Bigger banks could easily copy the portable mortgage if it gained customer acceptance, undermining E-Trade’s ability to profit from its first move.

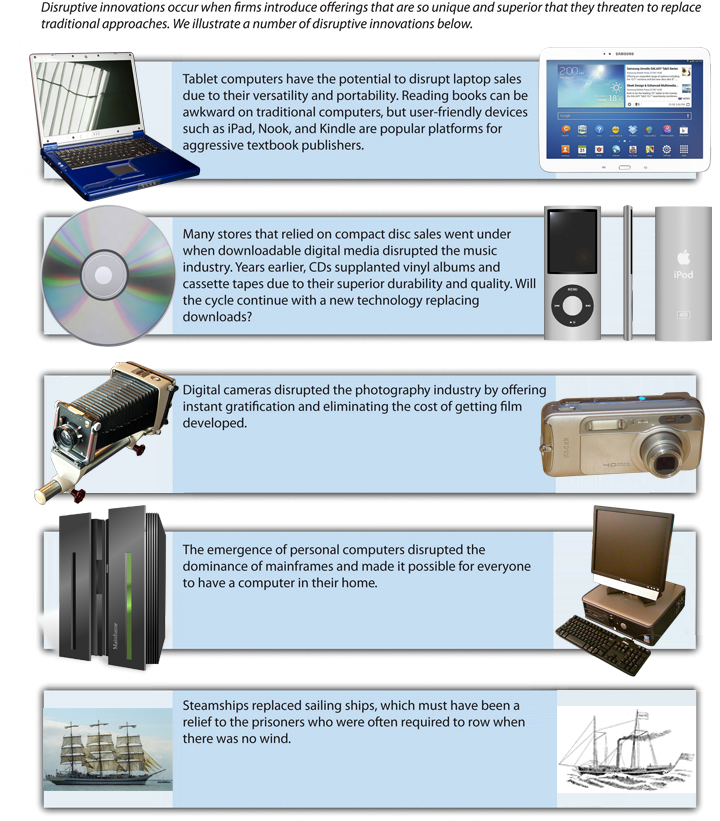

Disruptive Innovation

Some firms have the opportunity to shake up their industry by introducing a disruptive innovation[3]—an innovation that conflicts with, and threatens to replace, traditional approaches to competing within an industry (Figure 6.4 “Shaking the Market with Disruptive Innovations”). The iPad has proved to be a disruptive innovation since its introduction by Apple in 2010. Many individuals quickly abandoned clunky laptop computers in favor of the sleek tablet format offered by the iPad. And as a first mover, Apple was able to claim a large share of the market.

The iPad story is unusual for the speed of its adoption. Most disruptive innovations are not overnight sensations. Typically, a small group of customers embrace a disruptive innovation as early adopters and then a critical mass of customers builds over time. An example is digital cameras. Few photographers embraced digital cameras initially because they took pictures slowly and offered poor picture quality relative to traditional film cameras. As digital cameras have improved, however, they have gradually won over almost everyone that takes pictures. Interestingly, niche products have returned, such as polaroid instant cameras with self-developing film, and vinyl records. Executives who are deciding whether to pursue a disruptive innovation must first make sure that their firm can sustain itself during an initial period of slow growth.

Footholds

In warfare, many armies establish small positions in geographic territories that they have not occupied previously, probably because it is a lot to mount an attack on land than from the water. A beachhead can provide valuable competitive information at a relatively low cost (as compared to a full expansion strategy). These footholds provide value in at least three ways (Figure 6.5 “Footholds”). First, owning a foothold can dissuade other armies from attacking in the region. Second, owning a foothold gives an army a quick strike capability in a territory if the army needs to expand its reach. And finally, a beachhead may reveal how aggressively local competition will defend their territory.

Organizations may find it valuable to establish footholds in certain markets. Within the context of business, a foothold[4] is a small position that a firm intentionally establishes within a market in which it does not yet compete (Upson et al., 2014). Swedish furniture seller IKEA is a firm that relies on footholds. When IKEA enters a new country, it opens just one store. This store is then used as a showcase to establish IKEA’s brand. Once IKEA gains brand recognition in a country, more stores are established (Hambrick & Fredrickson, 2005).

Pharmaceutical giants such as Merck often obtain footholds in emerging areas of medicine, a different form of beachhead, often through acquisitions. For example, in December 2010 Merck purchased SmartCells Inc., a company that was developing a possible new treatment for diabetes. In May 2011, Merck acquired an equity stake in BeiGene Ltd., a Chinese firm that was developing novel cancer treatments and detection methods. Competitive moves such as these offer Merck relatively low-cost platforms from which it can expand if clinical studies reveal that the treatments are effective.

Blue Ocean Strategy

It is best to win without fighting.

– Sun-Tzu, The Art of War

A blue ocean strategy[5] involves creating a new, untapped market rather than competing with rivals in an existing market (Kim & Mauborgne, 2004). Based on a study of 150 strategic moves spanning more than a 100 years and thirty industries, the author’s demonstrated that companies can succeed not by battling competitors, but rather by creating ″blue oceans″ of uncontested market space. These strategic moves can create a leap in value for the company, its buyers, and its employees, while unlocking new demand and making the competition irrelevant. This strategy follows the approach recommended by the ancient master of strategy Sun-Tzu in the quote above. Instead of trying to outmaneuver its competition, a firm using a blue ocean strategy tries to make the competition irrelevant (Figure 6.6 “Blue ocean strategy”). Baseball legend Wee Willie Keeler offered a similar idea when asked how to become a better hitter: “Hit ’em where they ain’t.” In other words, hit the baseball where there are no fielders rather than trying to overwhelm the fielders with a ball hit directly at them.

Nintendo openly acknowledges following a blue ocean strategy in its efforts to invent new markets. In 2006, Perrin Kaplan, Nintendo’s vice president of marketing and corporate affairs for Nintendo of America, noted in an interview, “We’re making games that are expanding our base of consumers in Japan and America. Yes, those who’ve always played games are still playing, but we’ve got people who’ve never played to start loving it with titles like Nintendogs, Animal Crossing and Brain Games. These games are blue ocean in action” (Rosmarin, 2006). Other examples of companies creating new markets include FedEx’s invention of the fast-shipping business and eBay’s invention of online auctions.

Bricolage

Bricolage[6] is a concept that is borrowed from the arts and that, like blue ocean strategy, stresses moves that create new markets. Bricolage means using whatever materials and resources happen to be available as the inputs into a creative process. A good example is offered by one of the greatest inventions in the history of civilization: the printing press. As noted in the Wall Street Journal, “The printing press is a classic combinatorial innovation. Each of its key elements—the movable type, the ink, the paper and the press itself—had been developed separately well before Johannes Gutenberg printed his first Bible in the 15th century. Movable type, for instance, had been independently conceived by a Chinese blacksmith named Pi Sheng four centuries earlier. The press itself was adapted from a screw press that was being used in Germany for the mass production of wine (Johnson, 2010).” Gutenberg took materials that others had created and used them in a unique and productive way.

Compared to innovation, first mover and blue ocean strategies, frankly three other aspects far more often lead to initial success for early entrepreneurs. The three are combining existing products, incremental improvements in products and/or service, and new or expanded uses for products. As innovators, research shows a significantly higher percentage of success via improvements compared with truly new ideas, products or services.

Executives apply the concept of bricolage when they combine ideas from existing businesses to create a new business. Think miniature golf is boring? Not when you play at one of Monster Mini Golf’s more than twenty-five locations. This company couples a miniature golf course with the thrills of a haunted house. In April 2011, Monster Mini Golf announced plans to partner with the rock band KISS to create a “custom-designed, frightfully fun course [that] will feature animated KISS and monster props lurking in all 18 fairways” in Las Vegas (Monster Mini Golf, 2011).

Many an expectant mother has lamented the unflattering nature of maternity clothes and the boring stores that sell them. Coming to the rescue is Belly Couture, a boutique in Lubbock, Texas, that combines stylish fashion and maternity clothes. The store’s clever slogan—“Motherhood is haute”—reflects the unique niche it fills through bricolage. A wilder example is TURISAS, a Finnish rock band that has created a niche for itself by combining heavy metal music with the imagery and costumes of Vikings. The band’s website describes their effort at bricolage as “inspirational cinematic battle metal brilliance” (http://www.turisas.com/site/biography/). No one ever claimed that rock musicians are humble.

Strategy at the Movies

Love and Other Drugs

Competitive moves are chosen within executive suites, but they are implemented by frontline employees. Organizational success thus depends just as much on workers such as salespeople excelling in their roles as it does on executives’ ability to master strategy. A good illustration is provided in the 2010 film Love and Other Drugs, which was based on the nonfiction book Hard Sell: The Evolution of a Viagra Salesman.

As a new sales representative for drug giant Pfizer, Jamie Randall believed that the best way to increase sales of Pfizer’s antidepressant Zoloft in his territory was to convince highly respected physician Dr. Knight to prescribe Zoloft rather than the good doctor’s existing preference, Ely Lilly’s drug Prozac. Once Dr. Knight began prescribing Zoloft, thought Randall, many other physicians in the area would follow suit.

This straightforward plan proved more difficult to execute than Randall suspected. Sales reps from Ely Lilly and other pharmaceutical firms aggressively pushed their firm’s products, such as by providing all-expenses-paid trips to Hawaii for nurses in Dr. Knight’s office. Prozac salesman Trey Hannigan went so far as to beat up Randall after finding out that Randall had stolen and destroyed Prozac samples. While assault is an extreme measure to defend a sales territory, the actions of Hannigan and the other salespeople depicted in Love and Other Drugs reflect the challenges that frontline employees face when implementing executives’ strategic decisions about competitive moves.

Key Takeaway

- Firms can take advantage of a number of competitive moves to shake up or otherwise get ahead in an ever-changing business environment.

Exercises

- Find a key trend from the general environment and develop a blue ocean strategy that might capitalize on that trend.

- Provide an example of a product that, if invented, would work as a disruptive innovation. How widespread would be the appeal of this product?

- How would you propose to develop a new foothold if your goal was to compete in the fashion industry?

- Develop a new good or service applying the concept of bricolage. In other words, select two existing businesses and describe the experience that would be created by combining those two businesses.

References

Hambrick, D. C., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2005). Are you sure you have a strategy? Academy of Management Executive, 19, 51–62.

Johnson, S. (2010, September 25). The genius of the tinkerer. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703989304575503730101860838.html

Ketchen, D. J., Snow, C., & Street, V. (2004). Improving firm performance by matching strategic decision making processes to competitive dynamics. Academy of Management Executive, 19(4), 29–43.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2004, October). Blue ocean strategy. Harvard Business Review, 76–85.

Monster Mini Golf. (2011, April 28). KISS Mini Golf to rock Las Vegas this fall. Retrieved from http://www.monsterminigolf.com/mmgkiss.html

Rosmarin, R. (2006, February 7). Nintendo’s new look. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/2006/02/07/xbox-ps3-revolution-cx_rr_0207nintendo.html

Upson, J., Ketchen, D. J., Connelly, B., & Ranft, A. (2014, May 20). Competitor analysis and foothold moves. Academy of Management Journal.

- First mover: An initial entrant into a market. ↵

- First-mover advantage: When the initial move into a market allows a firm to establish a dominant position that other firms struggle to overcome. ↵

- Disruptive innovation: An improvement that conflicts with, and threatens to replace, traditional approaches to competing within an industry. ↵

- Foothold: A small position that a firm intentionally establishes within a market in which it does not yet compete. ↵

- Blue ocean strategy: Creating a new, untapped market rather than competing with rivals in an existing market. ↵

- Bricolage: Using whatever materials and resources happen to be available as the inputs into a creative process. ↵