4 Intended, Emergent, and Realized Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Learn what is meant by intended and emergent strategies and the differences between them.

- Understand realized strategies and how they are influenced by intended, deliberate, and emergent strategies.

A few years ago, a consultant posed a question to thousands of executives: “Is your industry facing overcapacity and fierce price competition?” All but one said “yes.” The only “no” came from the manager of a unique operation—the Panama Canal! And even there, they are building a second one connecting the Atlantic to Pacific oceans scheduled to open in 2015. This manager was fortunate to be in charge of a venture whose services are desperately needed by shipping companies and that offers the only simple route linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The canal’s current success will be challenged with this second goes into operation. With the current increase in globalization, the additional boat transportation make both canals appear to be guaranteed to have many customers for as long as anyone can see into the future.

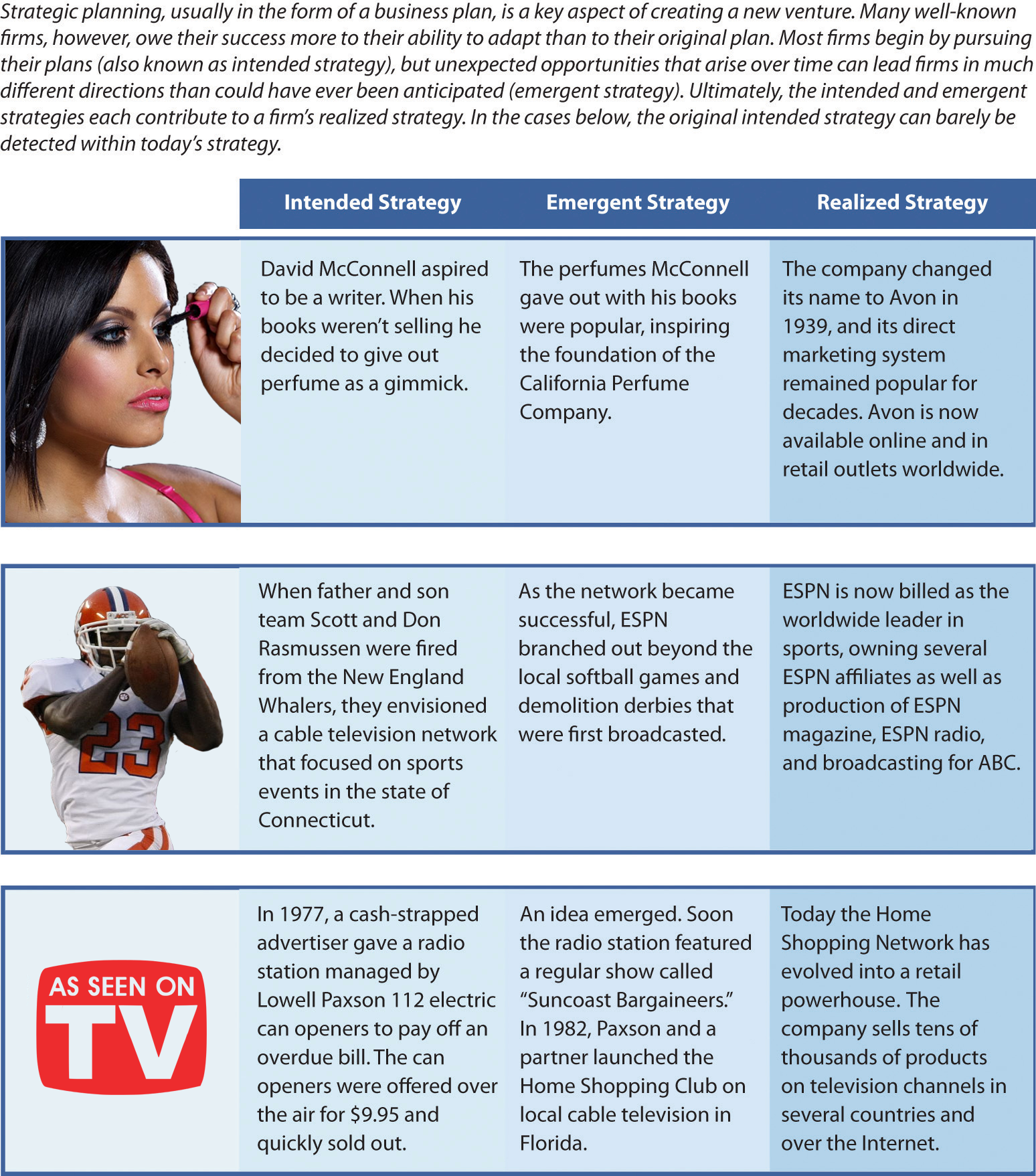

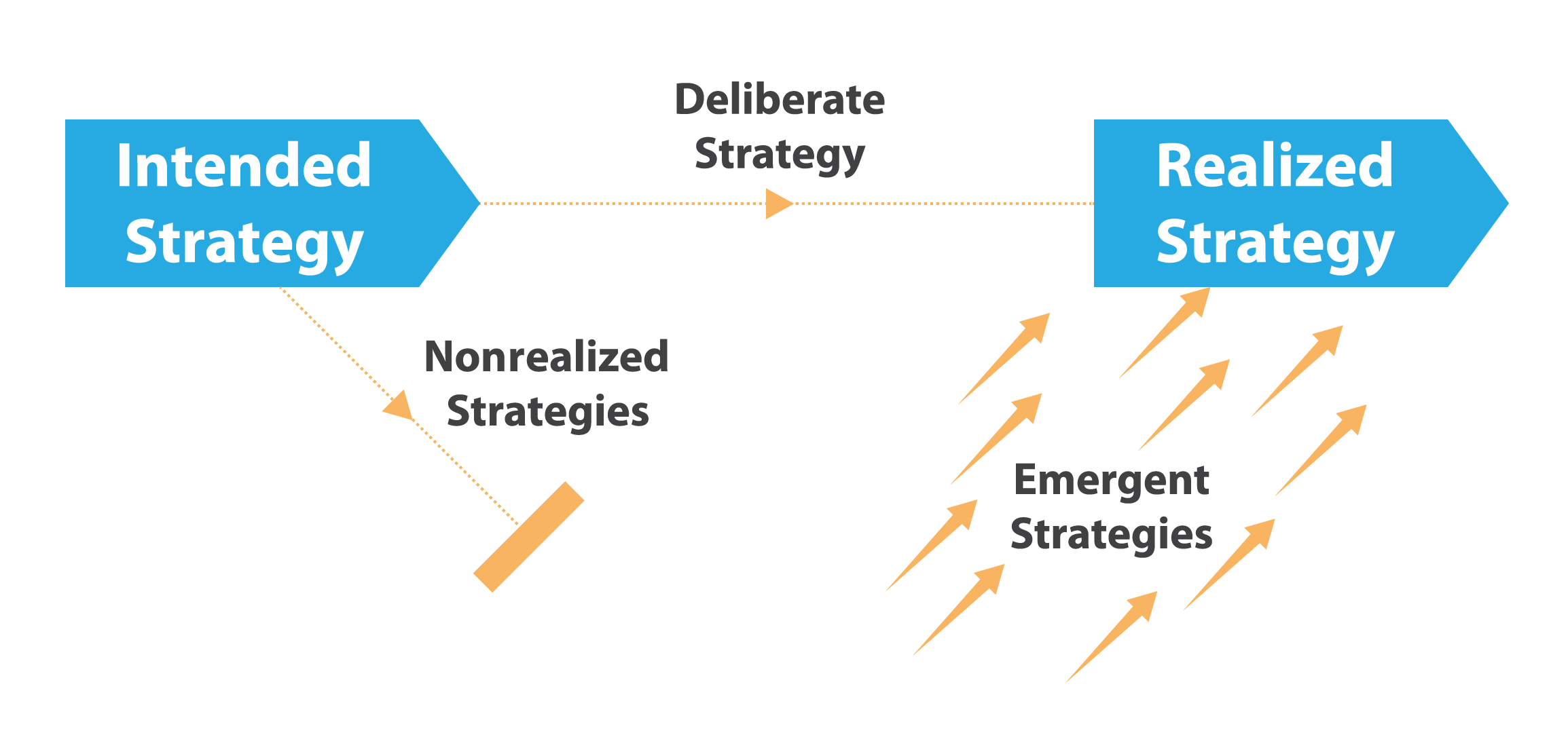

When an organization’s environment is stable and predictable, strategic planning can provide enough of a strategy for the organization to gain and maintain success. The executives leading the organization can simply create a plan and execute it, and they can be confident that their plan will not be undermined by changes over time. But as the consultant’s experience shows, only a few executives—such as the manager of the Panama Canal—enjoy a stable and predictable situation. Because change affects the strategies of almost all organizations, understanding the concepts of intended, emergent, and realized strategies is important (Figure 1.5 “Strategic Planning and Learning: Intended, Emergent, and Realized Strategies”). Also relevant are deliberate and nonrealized strategies. The relationships among these five concepts are presented in Figure 1.6 “A Model of Intended, Deliberate, and Realized Strategy” (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985).

Intended and Emergent Strategies

An intended strategy[1] is the strategy that an organization hopes to execute. Intended strategies are usually described in detail within an organization’s strategic plan. When a strategic plan is created for a new venture, it is called a business plan. As an undergraduate student at Yale in 1965, Frederick Smith had to complete a business plan for a proposed company as a class project. His plan described a delivery system that would gain efficiency by routing packages through a central hub and then pass them to their destinations. A few years later, Smith started Federal Express (FedEx), a company whose strategy closely followed the plan laid out in his class project. Today, Frederick Smith’s personal wealth has surpassed $2 billion, and FedEx ranks eighth among the World’s Most Admired Companies according to Fortune magazine. Certainly, Smith’s intended strategy has worked out far better than even he could have dreamed (Donahoe, 2011).

Emergent strategy has also played a role at Federal Express. An emergent strategy[2] is an unplanned strategy that arises in response to unexpected opportunities and challenges. Sometimes emergent strategies result in disasters. In the mid-1980s, FedEx deviated from its intended strategy’s focus on package delivery to capitalize on an emerging technology: facsimile (fax) machines. The firm developed a service called ZapMail that involved documents being sent electronically via fax machines between FedEx offices and then being delivered to customers’ offices. FedEx executives hoped that ZapMail would be a success because it reduced the delivery time of a document from overnight to just a couple of hours. Unfortunately, however, the ZapMail system had many technical problems that frustrated customers. Even worse, FedEx failed to anticipate that many businesses would simply purchase their own fax machines. ZapMail was shut down before long, and FedEx lost hundreds of millions of dollars following its failed emergent strategy. In retrospect, FedEx had made a costly mistake by venturing outside of the domain that was central to its intended strategy: package delivery (Funding Universe).

Emergent strategies can also lead to tremendous success. Southern Bloomer Manufacturing Company was founded to make underwear for use in prisons and mental hospitals. Many managers of such institutions believe that the underwear made for retail markets by companies such as Calvin Klein and Hanes is simply not suitable for the people under their care. Instead, underwear issued to prisoners needs to be sturdy and durable to withstand the rigors of prison activities and laundering. To meet these needs, Southern Bloomers began selling underwear made of heavy cotton fabric.

An unexpected opportunity led Southern Bloomer to go beyond its intended strategy of serving institutional needs for durable underwear. Just a few years after opening, Southern Bloomer’s performance was excellent. It was servicing the needs of about 125 facilities, but unfortunately, this was creating a vast amount of scrap fabric. An attempt to use the scrap as stuffing for pillows had failed, so the scrap was being sent to landfills. This was not only wasteful but also costly.

One day, cofounder Don Sonner visited a gun shop with his son. Sonner had no interest in guns, but he quickly spotted a potential use for his scrap fabric during this visit. The patches that the gun shop sold to clean the inside of gun barrels were of poor quality. According to Sonner, when he “saw one of those flimsy woven patches they sold that unraveled when you touched them, I said, ‘Man, that’s what I can do’” with the scrap fabric. Unlike other gun-cleaning patches, the patches that Southern Bloomer sold did not give off threads or lint, two by-products that hurt guns’ accuracy and reliability. The patches quickly became popular with the military, police departments, and individual gun enthusiasts. Before long, Southern Bloomer was selling thousands of pounds of patches per month. A casual trip to a gun store unexpectedly gave rise to a lucrative emergent strategy (Wells, 2002).

Realized Strategy

A realized strategy[3] is the strategy that an organization actually follows. Realized strategies are a product of a firm’s intended strategy (i.e., what the firm planned to do), the firm’s deliberate strategy[4] (i.e., the parts of the intended strategy that the firm continues to pursue over time), and its emergent strategy (i.e., what the firm did in reaction to unexpected opportunities and challenges). In the case of FedEx, the intended strategy devised by its founder many years ago—fast package delivery via a centralized hub—remains a primary driver of the firm’s realized strategy. For Southern Bloomers Manufacturing Company, realized strategy has been shaped greatly by both its intended and emergent strategies, which center on underwear and gun-cleaning patches.

In other cases, firms’ original intended strategies are long forgotten. A nonrealized strategy[5] refers to the abandoned parts of the intended strategy. When aspiring author David McConnell was struggling to sell his books, he decided to offer complimentary perfume as a sales gimmick. McConnell’s books never did escape the stench of failure, but his perfumes soon took on the sweet smell of success. The California Perfume Company was formed to market the perfumes; this firm evolved into the personal care products juggernaut known today as Avon. For McConnell, his dream to be a successful writer was a nonrealized strategy, but through Avon, a successful realized strategy was driven almost entirely by opportunistically capitalizing on change through emergent strategy.

Demographics

One often overlooked source of strategic information is demographics, which includes data on population, age, and sex. When we stop and think for a minute, we realize that age has a direct and obvious link to consumption—65-year-old men buy few disposable diapers, and teenage women buy few new cars! Similarly, if you examine the students in your class, the majority are probably between the ages of 18 and 24, the traditional age range when people acquire their post-secondary education. While today, the percentage of older students is low, demographic analysis tells us that this number will grow, if only because there will be fewer traditional-aged students in years to come. How do we know? Because we know the number of people aged 13 to 17 currently in your local high school.

Demographics analysis has a high degree of predictability. Someone who is 23 years old this year will predictably be 24 next year, and 25 the year after. Age data is often combined with a wide variety of economic and lifestyle information as well, dramatically increasing its strategic value to companies.

Canada’s baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1965) have had an incredible impact on everything from education and housing to health as they aged. This cohort, the earliest of which are now well into their 60s, are and will be purchasing products and services appropriate for newly retired seniors at record levels. However, those baby boomers are not having babies now (too old). In fact, Canada’s low birth rate of 1.61 children per woman in 2011 (Statistics Canada, 2013) will have a profound long-term effects on society; it takes 2.1 children per woman to sustain a nation’s population over time. Economists are asking, “What will happen when the population, especially the working-age population starts to fall?” (Statistics Canada, 2013).

This trend is observable in most countries around the world. With the United States reporting birth rates of 1.89 and China 1.58, immigration is unlikely to make up for these missing children. Interestingly, in Canada, Aboriginal people are an exception with a much higher birthrate. In fact, if this trend continues, Saskatchewan would become the first Canadian province with a majority Aboriginal population.

Understanding various demographic aspects of current consumers (from sales data) and analyzing how this might change over the medium-to-long term can be of real strategic importance to firms. Demographic data is readily available, usually free from government (Statistics Canada, U.S. Census Bureau, etc.), and customized data sets can be purchased to delve deeper into details of your relevant consumer population and population trends.

Strategy at the Movies

The Social Network

Did Harvard University student Mark Zuckerberg set out to build a billion-dollar company with more than 600 million active users? Not hardly. As shown in 2010’s The Social Network, Zuckerberg’s original concept in 2003 had a dark nature. After being dumped by his girlfriend, a bitter Zuckerberg created a website called “FaceMash” where the attractiveness of young women could be voted on. This evolved first into an online social network called Thefacebook that was for Harvard students only. When the network became surprisingly popular, it then morphed into Facebook, a website open to everyone. Facebook is so pervasive today that it has changed the way we speak, such as the word friend being used as a verb. Ironically, Facebook’s emphasis on connecting with existing and new friends is about as different as it could be from Zuckerberg’s original mean-spirited concept. Certainly, Zuckerberg’s emergent and realized strategies turned out to be far nobler than the intended strategy that began his adventure in entrepreneurship.

Key Takeaway

- Most organizations create intended strategies that they hope to follow to be successful. Over time, however, changes in an organization’s situation give rise to new opportunities and challenges. Organizations respond to these changes using emergent strategies. Realized strategies are a product of both intended and realized strategies.

Exercises

- What is the difference between an intended and an emergent strategy?

- Can you think of a company that seems to have abandoned its intended strategy? Why do you suspect it was abandoned?

- Would you describe your career strategy in college to be more deliberate or emergent? Why?

References

Donahoe, J. A. (2011, March 10). Forbes: Fred Smith’s fortune grows to $.21B. Memphis Business Journal. Retrieved from http://www.bizjournals.com/memphis/news/2011/03/10/forbes-fred-smiths-fortune-grows-to.html

Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6, 257–272.

Statistics Canada. (2013, March 19). Births and total fertility rate, by province and territory. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/hlth85b-eng.htm

Wells, K. (2002). Floating off the page: The best stories from the Wall Street Journal’s middle column. New York: Simon & Shuster. Quote from page 97.

- Intended strategy: The plan that an organization hopes to execute. ↵

- Emergent strategy: An unplanned direction that arises in response to unexpected opportunities and challenges. ↵

- Realized strategy: The plan of action that an organization actually follows. ↵

- Deliberate strategy: Parts of the intended plan that an organization continues to pursue over time. ↵

- Nonrealized strategy: Parts of the intended plan that are abandoned. ↵