8 Entrepreneurial Orientation

Learning Objectives

- Understand how thinking and acting entrepreneurially can help organizations and individuals.

- List and define the five dimensions of an entrepreneurial orientation.

The Value of Thinking and Acting Entrepreneurially

When asked to think of an entrepreneur, people typically offer examples such as John Molson, brothers Harrison and Wallace McCain, and J. A. Bombardier—individuals who have started their own successful businesses from the bottom up that generated a lasting impact on society. But entrepreneurial thinking and doing are not limited to those who begin in their garage with a new idea, financed by family members or personal savings. Some people in large organizations are filled with passion for a new idea, spend their time championing a new product or service, work with key players in the organization to build a constituency, and then find ways to acquire the needed resources to bring the idea to fruition.

Thinking and behaving entrepreneurially can help a person’s career too. Some enterprising individuals successfully navigate through the environments of their respective organizations and maximize their own career prospects by identifying and seizing new opportunities (Figure 2.9 “Understanding Entrepreneurial Orientation”) (Doetsch and Lindberg, 2013).

Almost three centuries ago, in the 1730s, Richard Cantillon used the French term entrepreneur, or literally “undertaker,” to refer to those who undertake self-employment while also accepting an uncertain return. In subsequent years, entrepreneurs have also been referred to as innovators of new ideas (Alexander Graham Bell), individuals who find and promote new combinations of factors of production (Bill Gates’s bundling of Microsoft’s products), and those who exploit opportunistic ideas to expand small enterprises (Jim Lazaridis at BlackBerry). The common elements of these conceptions of entrepreneurs are that they do something new and that some individuals can make something out of opportunities that others cannot.

Because the world is changing so rapidly, non-entrepreneurial organizations are at significant risk of being left behind. And companies left behind are often gone in fairly short order. Even a cursory self-examination of the products and service we use daily, reveal than many of these were not even invented five to ten years ago. Smart phones are just one example.

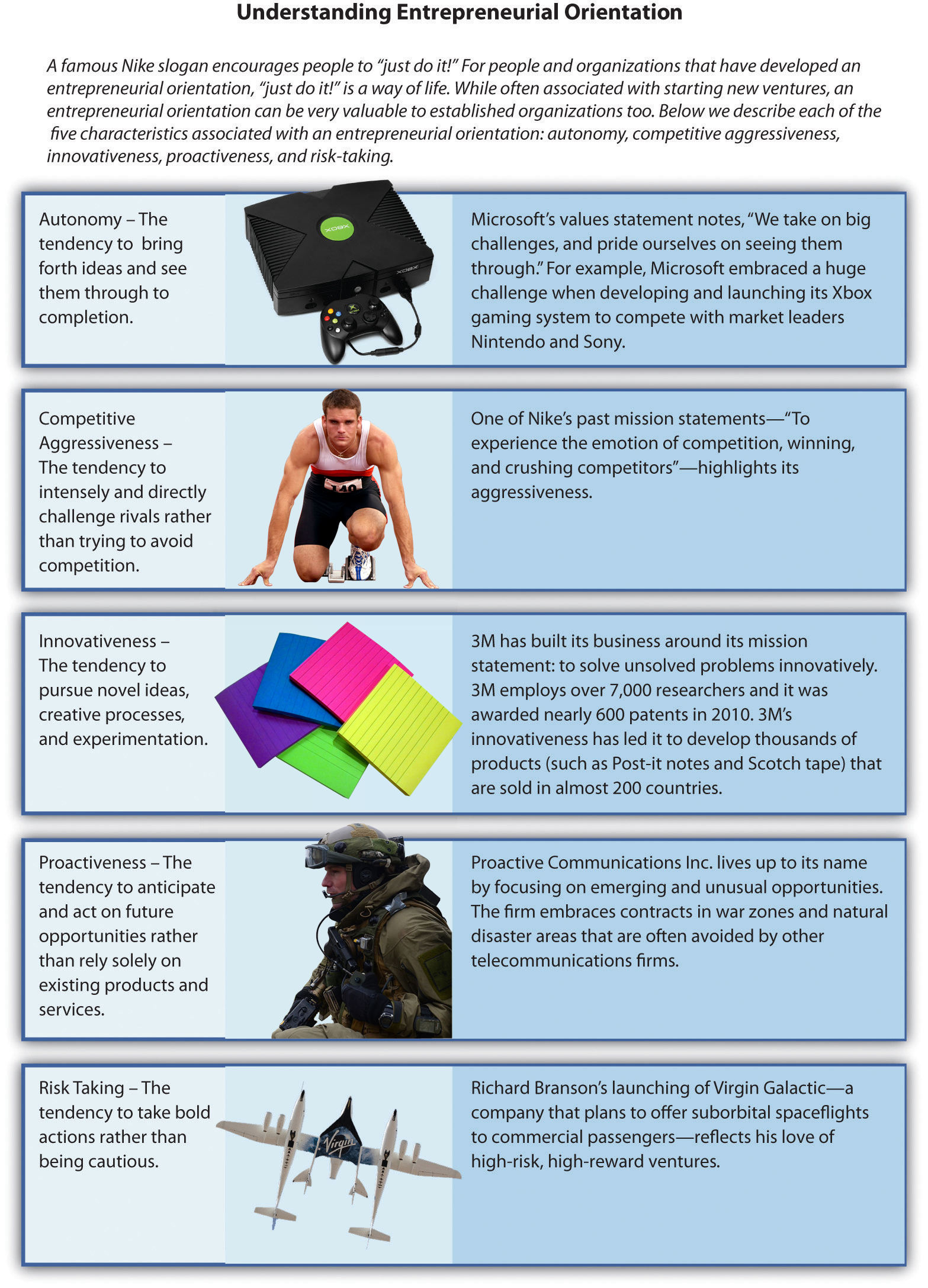

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)[2] is a key concept when executives are crafting strategies in the hopes of doing something new and exploiting opportunities that other organizations cannot exploit. EO refers to the processes, practices, and decision-making styles of organizations that act entrepreneurially. Any organization’s level of EO can be understood by examining how it stacks up relative to five dimensions:

(1) autonomy,

(2) competitive aggressiveness,

(3) innovativeness,

(4) proactiveness, and

(5) risk taking.

These dimensions are also relevant to individuals.

Autonomy

Autonomy[3] refers to whether an individual or team of individuals within an organization has the freedom to develop an entrepreneurial idea and then see it through to completion. In an organization that offers high autonomy, people are offered the independence required to bring a new idea to fruition, unfettered by the shackles of corporate bureaucracy. When individuals and teams are unhindered by organizational traditions and norms, they are able to more effectively investigate and champion new ideas.

Some large organizations promote autonomy by empowering a division to make its own decisions, set its own objectives, and manage its own budgets, One example is the $110 million Canadarm development program, largely carried out by Canadian industry under the direction of the National Research Council of Canada. The industrial team, led by Spar Aerospace Ltd., included CAE Electronics Ltd. and DSMA Atcon Ltd. The Canadarm was signed over to NASA in February 1981, at Spar’s Toronto plant. (Canadian Encyclopedia) Another, Skunk Works, is an official alias for Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs (ADP), formerly called Lockheed Advanced Development Projects. Skunk Works is responsible for a number of famous aircraft designs, including the U-2, the SR-71 Blackbird, the F-117 Nighthawk, and the F-22 Raptor (Wikipedia, 2014).

Competitive Aggressiveness

Competitive aggressiveness is the tendency to intensely and directly challenge competitors rather than trying to avoid them. Aggressive moves can include price-cutting and increasing spending on marketing, quality, and production capacity. An example of competitive aggressiveness can be found in any number of “attack ads” in the political arena. When Justin Trudeau became the leader of the Liberal Party in Canada, he was subject to ads targeting his judgment and, specifically, recent comments on the economy, terrorism, and the legalization of marijuana (Maloney, 2014).

Sometimes aggressive moves can backfire. During the 1993 Canadian federal election, the Progressive Conservative Party produced a televised attack ad against Jean Chrétien, the Liberal leader. The ad (sometimes referred to as the “face ad”) was perceived by many as a focus on Chrétien’s facial deformity, caused by Bell’s palsy. The resulting outcry is considered to be an example of voter backlash from negative campaigning (Wikipedia, 2014).

Too much aggressiveness can undermine an organization’s success. A small firm that attacks larger rivals, for example, may find itself on the losing end of a price war. Establishing a reputation for competitive aggressiveness can damage a firm’s chances of being invited to join collaborative efforts such as joint ventures and alliances. In some industries, such as the biotech industry, collaboration is vital because no single firm has the knowledge and resources needed to develop and deliver new products. Executives thus must be wary of taking competitive actions that destroy opportunities for future collaborating.

Innovativeness

Innovativeness[4] is the tendency to pursue creativity and experimentation. Some innovations build on existing skills to create incremental improvements, while more radical innovations require brand-new skills and may make existing skills obsolete. Either way, innovativeness is aimed at developing new products, services, and processes. Those organizations that are successful in their innovation efforts tend to enjoy stronger performance than those that do not.

Known for efficient service, FedEx has introduced its Smart Package, which allows both shippers and recipients to monitor package location, temperature, and humidity. This type of innovation is a welcome addition to FedEx’s lineup for those in the business of shipping delicate goods, such as human organs. How do firms generate these types of new ideas that meet customers’ complex needs? Perennial innovators 3M and Google have found a few possible answers. 3M sends 9,000 of its technical personnel in thirty-four countries into customers’ workplaces to experience firsthand the kinds of problems customers encounter each day. Google’s two most popular features of its Gmail, thread sorting and unlimited email archiving, were first suggested by an engineer who was fed up with his own email woes. Both firms allow employees to use a portion of their work time on projects of their own choosing with the goal of creating new innovations for the company. This latter example illustrates how multiple EO dimensions—in this case, autonomy and innovativeness—can reinforce one another.

Proactiveness

Proactiveness[5] is the tendency to anticipate and act on future needs rather than reacting to events after they unfold. A proactive organization is one that adopts an opportunity-seeking perspective. Such organizations act in advance of shifting market demand and are often either the first to enter new markets or “fast followers” that improve on the initial efforts of first movers.

Consider Proactive Communications, an aptly named small firm in Killeen, Texas. From its beginnings in 2001, this firm has provided communications in hostile environments, such as Iraq and areas impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Being proactive in this case means being willing to don a military helmet or sleep outdoors—activities often avoided by other telecommunications firms. By embracing opportunities that others fear, Proactive’s executives have carved out a lucrative niche in a world that is technologically, environmentally, and politically turbulent.

Risk Taking

Risk taking[6] refers to the tendency to engage in bold rather than cautious actions. Starbucks, for example, made a risky move in 2009 when it introduced a new instant coffee called VIA Ready Brew. Instant coffee has long been viewed by many coffee drinkers as a bland drink, but Starbucks decided that the opportunity to distribute its product in different “make-at-home” format was worth the risk of associating its brand name with instant coffee.

Although a common belief about entrepreneurs is that they are chronic risk takers, research suggests that entrepreneurs do not perceive their actions as risky, and most take action only after using planning and forecasting to reduce uncertainty. But uncertainty seldom can be fully eliminated. A few years ago, Jeroen van der Veer, CEO of Royal Dutch Shell PLC, entered a risky energy deal in Russia’s far east. At the time, van der Veer conceded that it was too early to know whether the move would be successful. Just six months later, however, customers in Japan, Korea, and the United States had purchased all the natural gas expected to be produced there for the next twenty years. If political instabilities in Russia and challenges in pipeline construction do not dampen returns, Shell stands to post a hefty profit from its 27.5 percent stake in the venture.

Building an Entrepreneurial Orientation

Steps can be taken by executives to develop a stronger entrepreneurial orientation throughout an organization and by individuals to become more entrepreneurial themselves. For executives, it is important to design organizational systems and policies to reflect the five dimensions of EO. As an example, how an organization’s compensation systems encourage or discourage these dimensions should be considered. Is taking sensible risks rewarded through raises and bonuses, regardless of whether the risks pay off, for example, or does the compensation system penalize risk taking? Other organizational characteristics such as corporate debt level may influence EO. Do corporate debt levels help or impede innovativeness? Is debt structured in such a way as to encourage risk taking? These are key questions for executives to consider.

Examination of some performance measures can assist executives in assessing EO within their organizations. To understand how the organization develops and reinforces autonomy, for example, top executives can administer employee satisfaction surveys and monitor employee turnover rates. Organizations that effectively develop autonomy should foster a work environment with high levels of employee satisfaction and low levels of turnover. Innovativeness can be gauged by considering how many new products or services the organization has developed in the last year and how many patents the firm has obtained.

Similarly, individuals should consider whether their attitudes and behaviors are consistent with the five dimensions of EO. Is an employee making decisions that focus on competitors? Does the employee provide executives with new ideas for products or processes that might create value for the organization?

Is the employee making proactive as opposed to reactive decisions? Each of these questions will aid employees in understanding how they can help to support EO within their organizations.

Key Takeaway

- Building an entrepreneurial orientation can be valuable to organizations and individuals alike in identifying and seizing new opportunities. Entrepreneurial orientation consists of five dimensions: (1) autonomy, (2) competitive aggressiveness, (3) innovativeness, (4) proactiveness, and (5) risk taking.

Exercises

- Can you name three firms that have suffered because of lack of an entrepreneurial orientation?

- Identify examples of each dimension of entrepreneurial orientation other than the examples offered in this section.

- How does developing an entrepreneurial orientation have implications for your future career choices?

- How could you apply the dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to a job search?

References

Certo, S. T., Connelly, B., & Tihanyi, L. (2008). Managers and their not-so-rational decisions. Business Horizons, 51(2), 113–119.

Certo, S. T., Moss, T. W., & Short, J. C. 2009. Entrepreneurial orientation: An applied perspective. Business Horizons, 52, 319–324.

Doetsch, K. and Lindberg, G. (2013, June 16). Canadarm. Retrieved from Historica Canada website http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadarm/

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21, 135–172.

Maloney, R. (2014 March 14). The Trudeau Attack Ads Tories Don’t Want You To See… Retrieved from The Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2014/03/14/trudeau-attack-ads-2014-online_n_4965474.html

Simon, M., Houghton, S. M., & Aquino, K. 2000. Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 14, 113–134.

Wikipedia Org. (2014, May 20). 1993 Chrétien attack ad. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1993_Chrétien_attack_ad

Wikipedia Org. (2014, May 26). Skunk Works. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skunk_Works

- This section is adapted from Certo, S. T., Moss, T. W., & Short, J. C. 2009. Entrepreneurial orientation: An applied perspective. Business Horizons, 52, 319–324. ↵

- Entrepreneurial orientation (EO): The processes, practices, and decision-making styles of organizations that act entrepreneurially. ↵

- Autonomy: Whether an individual or team of individuals within an organization has the freedom to develop an entrepreneurial idea and then see it through to completion. ↵

- Innovativeness: The tendency to pursue creativity and experimentation. ↵

- Proactiveness: The tendency to anticipate and act on future needs. ↵

- Risk taking: The tendency to engage in bold rather than cautious actions. ↵