61 Boards of Directors

Learning Objectives

- Understand the key roles played by boards of directors.

- Know how CEO pay and perks impact the landscape of corporate governance.

- Explain different terms associated with corporate takeovers.

The Many Roles of Boards of Directors

“You’re fired!” is a commonly used phrase most closely associated with Donald Trump as he dismisses candidates on his reality show, Celebrity Apprentice. But who would have the power to utter these words to today’s CEOs, whose paychecks are on par with many of the top celebrities and athletes in the world? This honor belongs to the board of directors[1]—a group of individuals that oversees the activities of an organization or corporation.

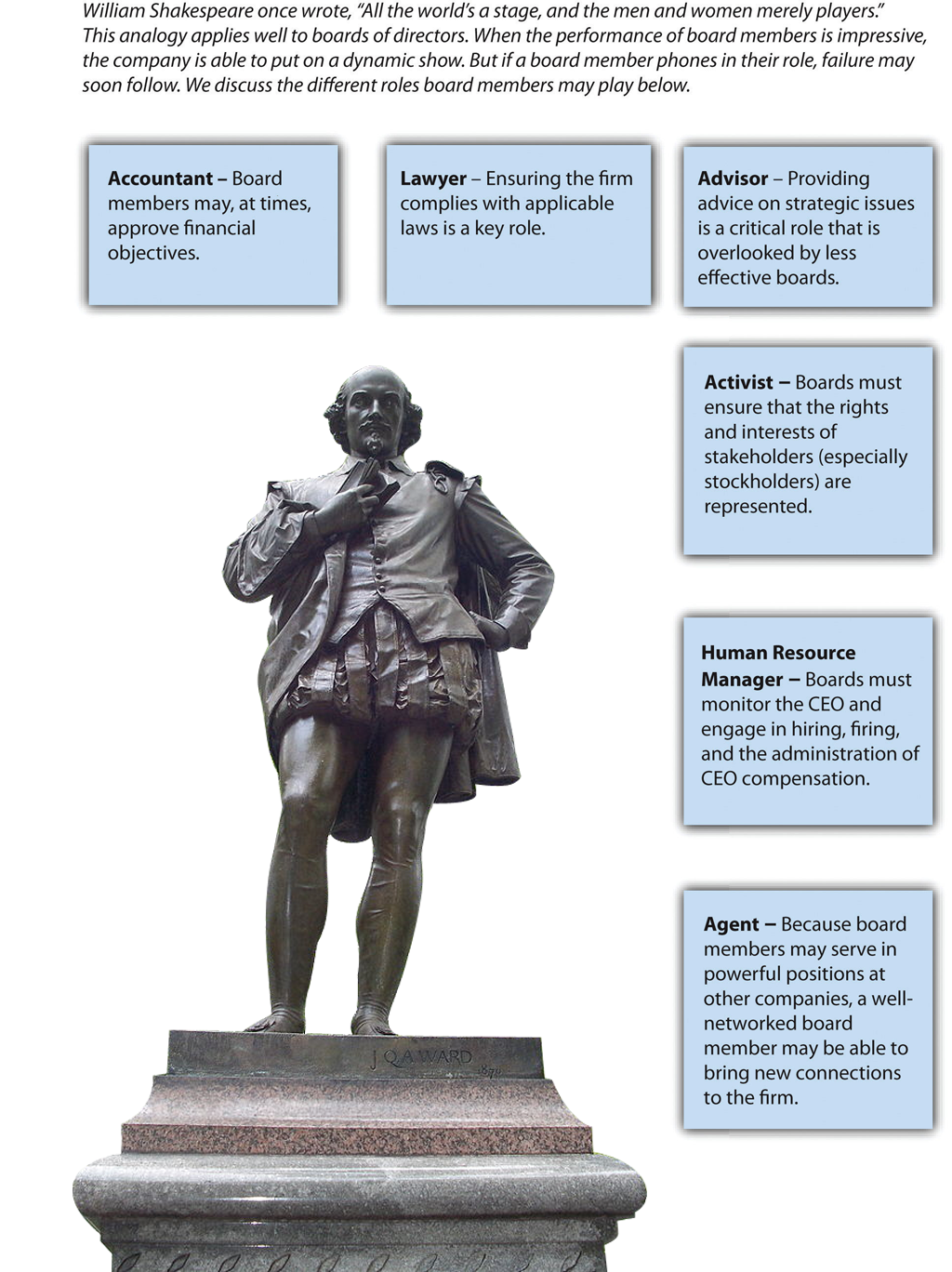

The ability to appoint, or dis-appoint(!), CEOs is arguably the most important task of the board of directors in effective corporate governance[2] for the firm. An effective board plays many roles, ranging from the approval of annual budgets and financial objectives, advising on strategic issues, making the firm aware of relevant laws, and representing stakeholders[3] who have an interest in the long-term performance of the firm (Figure 10.1 “Board Roles”). Effective boards may help bring prestige and important resources to the organization. For example, Air Canada’s board often includes the CEOs of other firms as well as former high-ranking politicians and prestigious academics.

The key stakeholder of most corporations is generally agreed to be the shareholders of the company’s stock. Most large, publicly traded firms in Canada are made up of thousands of shareholders. While 5 percent ownership in many ventures may seem modest, this amount is considerable in publicly traded companies where such ownership is generally limited to other companies, and ownership in this amount could result in representation on the board of directors.

The possibility of conflicts of interest is considerable in public corporations. On the one hand, CEOs favor large salaries and job stability, and these desires are often accompanied by a tendency to make decisions that would benefit the firm (and their salaries) in the short term at the expense of decisions considered over a longer time horizon, when they may no longer be the CEO. In contrast, shareholders prefer decisions that will grow the value of their stock in the long term. This separation of interest creates an agency problem[4] wherein the interests of the individuals that manage the company (agents such as the CEO) may not align with the interest of the owners (such as stockholders).

The composition of the board is critical because the dynamics of the board play an important part in resolving the agency problem. However, who exactly should be on the board is an issue that has been subject to fierce debate. CEOs often favor the use of board insiders[5] who often have intimate knowledge of the firm’s business affairs. In contrast, many institutional investors[6] such as mutual funds and pension funds that hold large blocks of stock in the firm often prefer significant representation by board outsiders[7] that provide a fresh, nonbiased perspective concerning a firm’s actions.

One particularly controversial issue in regard to board composition is the potential for CEO duality,[8] a situation in which the CEO is also the chairman of the board of directors. This has also been known to create a bitter divide within a corporation.

For example, during the 1990s, the Walt Disney Company was often listed in BusinessWeek’s rankings for having one of the worst boards of directors (Lavelle, 2002). In 2005, Disney’s board forced the separation of then CEO (and chairman of the board) Michael Eisner’s dual roles. Eisner retained the role of CEO but later stepped down from Disney entirely. Disney’s story reflects a changing reality that boards are acting with considerably more influence than in previous decades when they were viewed largely as rubber stamps that generally folded to the whims of the CEO.

Managing CEO Compensation

One of the most visible roles of boards of directors is setting CEO pay. The valuation of the human capital associated with the rare talent possessed by some CEOs can be illustrated in a story of an encounter one tourist had with the legendary artist Pablo Picasso. As the story goes, Picasso was once spotted by a woman sketching. Overwhelmed with excitement at the serendipitous meeting, the tourist offered Picasso fair market value if he would render a quick sketch of her image. After completing his commission, she was shocked when he asked for 5,000 francs, responding, “But it only took you a few minutes.” Undeterred, Picasso retorted, “No, it took me all my life” (Kay, 1999).

This story illustrates the complexity associated with managing CEO compensation. On the one hand, large corporations must pay competitive wages for the scarce talent that is needed to manage billion-dollar corporations. In addition, like celebrities and sport stars, CEO pay is much more than a function of a day’s work for a day’s pay. CEO compensation is a function of the competitive wages that other corporations would offer for a potential CEO’s services.

On the other hand, boards will face considerable scrutiny from investors if CEO pay is out of line with industry norms. From 1980 to 2000, the gap between CEO pay and worker pay grew from 42 to 1 to 475 to 1 (Blumenthal, 2000). Although efforts to close this gap have been made, as recently as 2008 reports indicate the ratio continues to be as high as 344 to 1, much higher than other countries, where an 80 to 1 ratio is common, or in Japan where the gap is just 16 to 1 (Feltman, 2009). Meanwhile, shareholders need to be aware that research studies have found that CEO pay is positively correlated with the size of firms—the bigger the firm, the higher the CEO’s compensation (Tosi et al., 2000). Consequently, when a CEO tries to grow a company, such as by acquiring a rival firm, shareholders should question whether such growth is in the company’s best interest or whether it is simply an effort by the CEO to get a pay raise.

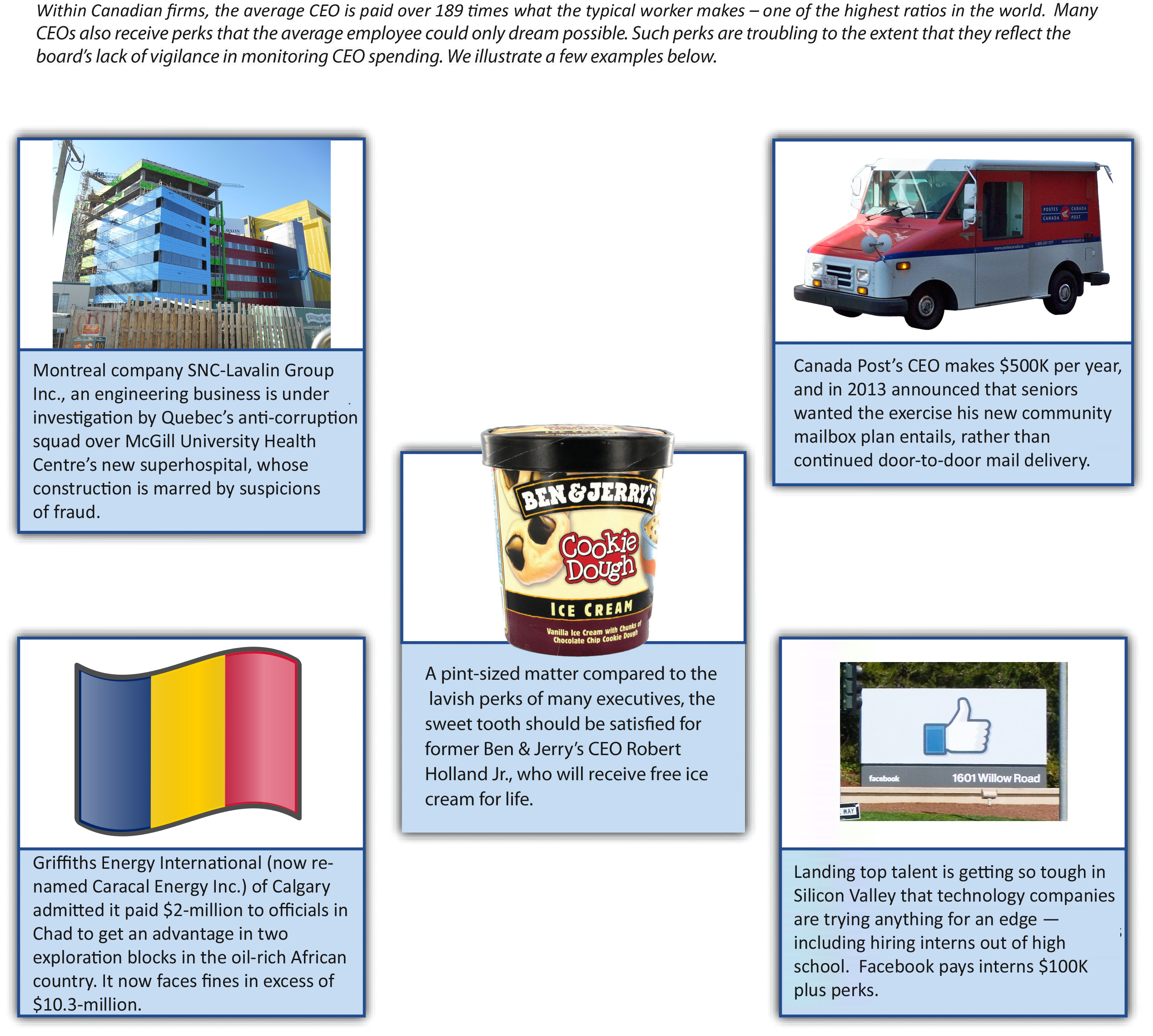

In most publicly traded firms, CEO compensation generally includes guaranteed salary, cash bonus, and stock options. But perks provide another valuable source of CEO compensation (Figure 10.3 “CEO Perks”). In addition to the controversy surrounding CEO pay, such perks associated with holding the position of CEO have also come under considerable scrutiny. The term perks, derived from perquisite, refers to special privileges, or rights, as a function of one’s position. Executives often receive additional or supplemental benefits and perquisites, which may include a special retirement plan, a deferred compensation plan, extra insurance coverage, extra vacation, a company car, a chauffeur, use of the company plane, club memberships, financial and legal counseling, and so on. Many executive compensation packages even include the kitchen sink—literally. A quick review of public filings reveals numerous executives with company-provided or subsidized housing

CEO perks have ranged in magnitude from the sweet benefit of ice cream for life given to former Ben & Jerry’s CEO Robert Holland, to much more extreme benefits that raise the ire of investors while outraging employees. One such perk was provided to John Thain, who, as former head of NYSE Euronext, received more than $1 million to renovate his office. While such perks may provide powerful incentives to stay with a company, they may result in considerable negative press and serve only to motivate vigilant investors wary of the value of such investments to shop elsewhere.

The Market for Corporate Governance

An old investment cliché encourages individuals to buy low and sell high. When a publicly traded firm loses value, often due to lack of vigilance on the part of the CEO and/or board, a company may become a target of a takeover wherein another firm or set of individuals purchases the company. Generally, the top management team is replaced, and those who survive the cut are charged with revitalizing the firm and maximizing its assets.

In some cases, the takeover is in the form of a leveraged buyout (LBO)[9] in which a publicly traded company is purchased and then taken off the stock market. One of the most famous LBOs was of RJR Nabisco, which inspired the book (and later film) Barbarians at the Gate. LBOs historically are associated with reduction in workforces to streamline processes and decrease costs. The managers who instigate buyouts generally bring a more entrepreneurial mind-set to the firm with the hopes of creating a turnaround from the same fate that made the company an attractive takeover target (recent poor performance) (Wright, Hoskisson, & Busenitz, 2001).

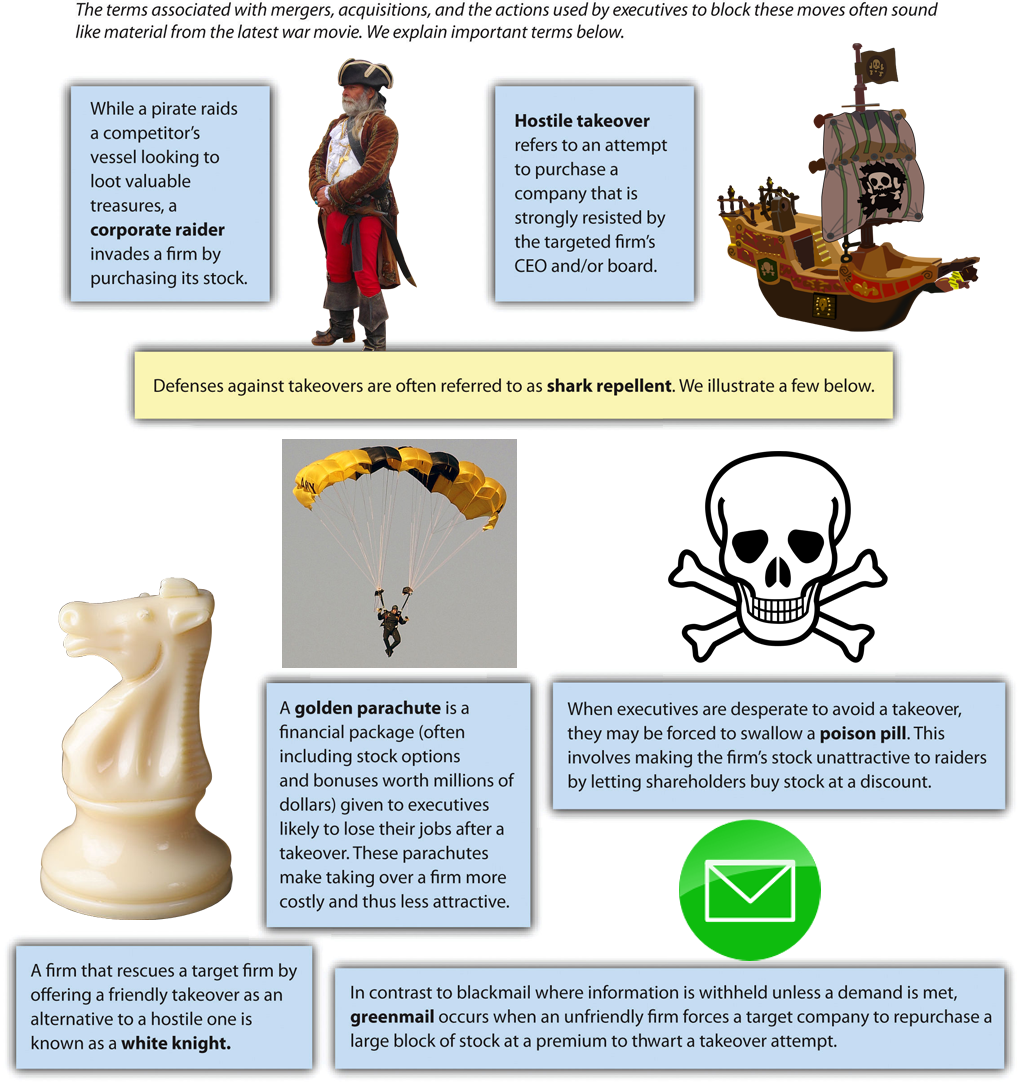

Many takeover attempts temporarily increase shareholder value. However, the data shows that such takeovers and mergers have a relatively poor longer-term return on investment. Because most takeovers are associated with the dismissal of previous management, the terminology associated with change of ownership has a decidedly negative slant against the acquiring firm’s management team. For example, individuals or firms that hope to conduct a takeover are often referred to as corporate raiders[10]. An unsolicited takeover attempt is often dubbed a hostile takeover,[11] with shark repellent[12] as the potential defenses against such attempts. Although the poor management of a targeted firm is often the reason such businesses are potential takeover targets, when another firm that may be more favorable to existing management enters the picture as an alternative buyer, a white knight[13] is said to have entered the picture (Figure 10.4 “Takeover Terms”).

The negative tone of takeover terminology also extends to the potential target firm. There is an inherent conflict of interest as CEOs, senior executives and board members are likely to lose their positions after a successful takeover occurs. A number of antitakeover tactics have been used by boards to deter a corporate raid. For example, many firms are said to pay greenmail[14] by repurchasing large blocks of stock at a premium to avoid a potential takeover. Firms may threaten to take a poison pill[15] where additional stock is sold to existing shareholders, increasing the shares needed for a viable takeover. Even if the takeover is successful and the previous CEO is dismissed, a golden parachute[16] that includes a lucrative financial settlement is likely to provide a soft landing for the ousted executive.

Key Takeaway

- Firms can benefit from superior corporate governance mechanisms such as an active board that monitors CEO actions, provides strategic advice, and helps network other useful resources. When such mechanisms are not in place, CEO excess may go unchecked, resulting in negative publicity, poor firm performance, and even potential takeover by other firms.

Exercises

- Divide the class into teams and see who can find the most egregious CEO perk in the last year.

- Find a listing of members of a board of directors for a Fortune 500 firm. Does the board seem to be composed of individuals who are likely to fulfill all the board roles effectively?

- Research a hostile takeover in the past five years and examine the long-term impact on the firm’s stock market performance. Was the takeover beneficial or harmful for shareholders?

- Examine the AFL-CIO Executive Paywatch website (http://www.aflcio.org/corporatewatch/paywatch) and select a company of interest to see how many years you would need to work to earn a year’s pay enjoyed by the firm’s CEO.

References

Blumenthal, R. G. (2000, September 4). The pay gap between workers and chiefs looks like a chasm. Barron’s, 10.

Bunting, C. (2011, February 23). Board of dreams: Fantasy board of directors. Business News Daily. Retrieved from http://www.businessnewsdaily.com/681-board-of-directors-fantasy-picks-small-business.html

CBC. (2012, January 3). Richest CEOs earn 189 times average Canadian. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/richest-ceos-earn-189-times-average-canadian-1.1193266

Coleman, W. (2014). Executive Compensation: Executive Negotiation Checklist. Salary.com. Retrieved from http://www.salary.com/executive-compensation-executive-negotiation-checklist/

Cousineau, S. (2013, February 27). SNC: A scandal that won’t die and shares that won’t sink. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/snc-a-scandal-that-wont-die-and-shares-that-wont-sink/article9134773/#dashboard/follows/

Feltman, P. (2009). Experts examine pay disparity, other executive compensation issues. SEC Filings Insight, 15, 1–6.

Frier, S. (2014, July 8). Facebook woos teens with cushy internships. Toronto Star Newspapers. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com/business/tech_news/2014/07/08/facebook_woos_teens_with_cushy_internships.html

Gerson, J. (2013, January 22). Calgary energy firm charged $10.3M after pleading guilty to $2M bribe attempt of Chad ambassador. National Post. Retrieved from http://news.nationalpost.com/2013/01/22/calgary-energy-firm-charged-10-3m-after-pleading-guilty-to-2m-bribe-attempt-of-chad-ambassador/

Kay, I. (1999). Don’t devalue human capital. Wall Street Journal—Eastern Edition, 233, A18.

Lavelle, L. (2002, October 7). The best and worst boards: How corporate scandals are sparking a revolution in governance. BusinessWeek, 104.

Tosi, H. L., Werner, S., Katz., J. P., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2000). How much does performance matter? A meta-analysis of CEO pay studies. Journal of Management, 26, 301–339.

Wright, M., Hoskisson, R. E., & Busenitz, L. W. (2001). Firm rebirth: Buyouts as facilitators of strategic growth and entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Executive, 15, 111–125.

- Board of directors: A group of individuals, either elected or appointed, that oversees the activities of an organization or corporation. ↵

- Effective corporate governance: The processes, policies, and laws that govern an organization (often corporations) establish accountability and try to eliminate conflicts of interest associated with the principle-agent problems. ↵

- Stakeholders: Individuals and groups that have an interest to stake a claim in an organization. ↵

- Agency problem: The interest of individuals that act as agents to manage the company may not align with the interest of the firm’s stockholders. ↵

- Board insiders: Members of the board of directors that are generally employed inside of the organization. ↵

- Institutional investors: Organizations that invest large sums of money into a broad portfolio of holding, such as banks, retirement funds, mutual funds, and pension funds. ↵

- Board outsiders: Members of the board of directors that are generally employed outside of the organization. ↵

- CEO duality: When the chief executive officer is also the chairman of the board of directors. ↵

- Leveraged buyout (LBO): A company that is purchased through significant debt. ↵

- Corporate raiders: An individual or firm that purchases stock in another firm with the goal of an eventual takeover. ↵

- Hostile takeover: An attempt to purchase a company that is strongly resisted by the targeted firm’s CEO and/or board. ↵

- Shark repellent: Defenses against takeover attempts. ↵

- White knight: A firm that rescues a target firm by offering a friendly takeover as an alternative to a hostile one. ↵

- Greenmail: An unfriendly firm forces a target company to repurchase a large block of stock at a premium to thwart a takeover attempt. ↵

- Poison pill: An attempt to make the firm’s stock unattractive to raiders by letting shareholders buy stock at a discount, which creates a conversion of equity to debt that makes the firm less attractive. ↵

- Golden parachute: A financial package (often including stock options and bonuses worth millions of dollars) given to executives likely to lose their jobs after a takeover. ↵