Positionality

David Szanto and Courtney Strutt

David Szanto is a teacher, consultant, and artist taking an experimental approach to gastronomy and food systems. Past projects include meal performances about urban foodscapes, immersive sensory installations, and interventions involving food, microbes, humans, and digital technology. David has taught at several universities in Canada and Europe and has written extensively on food, art, and performance.

Courtney Strutt is a white settler educator and community development practitioner based out of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Using a lens of decolonization and social justice, Courtney’s work spans municipal emergency food system response planning, supporting local Indigenous food sovereignty movements, and addressing climate change through teaching and municipal policy making.

What if we could look at the Big Dipper from Alpha Centauri?

The ways we perceive a given situation depends on how we look at it, both literally and figuratively. That ‘stance’ is called positionality. It includes our physical placement relative to what we are looking at (e.g., near/far, above/below, inside/outside), as well a more figurative kind of placement. Figurative positionality relates to our formal and social education, upbringing and culture, personal experiences, race, class, age, gender, and other characteristics. These aspects of our identity act like a series of disciplinary, emotional, and cognitive lenses that influence how we view the world.

In some ways, positionality is like subjectivity, meaning that ‘reality’ depends on myriad individual ways of understanding the world. In academic research, acknowledging positionality is very important, because it allows the audiences of our research to understand the inherent biases in our work. Even in so-called objective or scientific research, positionality plays a role. (Think about how differently a physicist and a biologist might view and describe the role of carbon or hydrogen in their work.)

It can be hard to step out of our own frames of reference to understand our disciplinary, emotional, and cognitive positionality. (Frames of reference are the ways we understand everything, after all, including ourselves.) Fortunately, to better understand figurative positionality, the more concrete example of physical positionality can help.

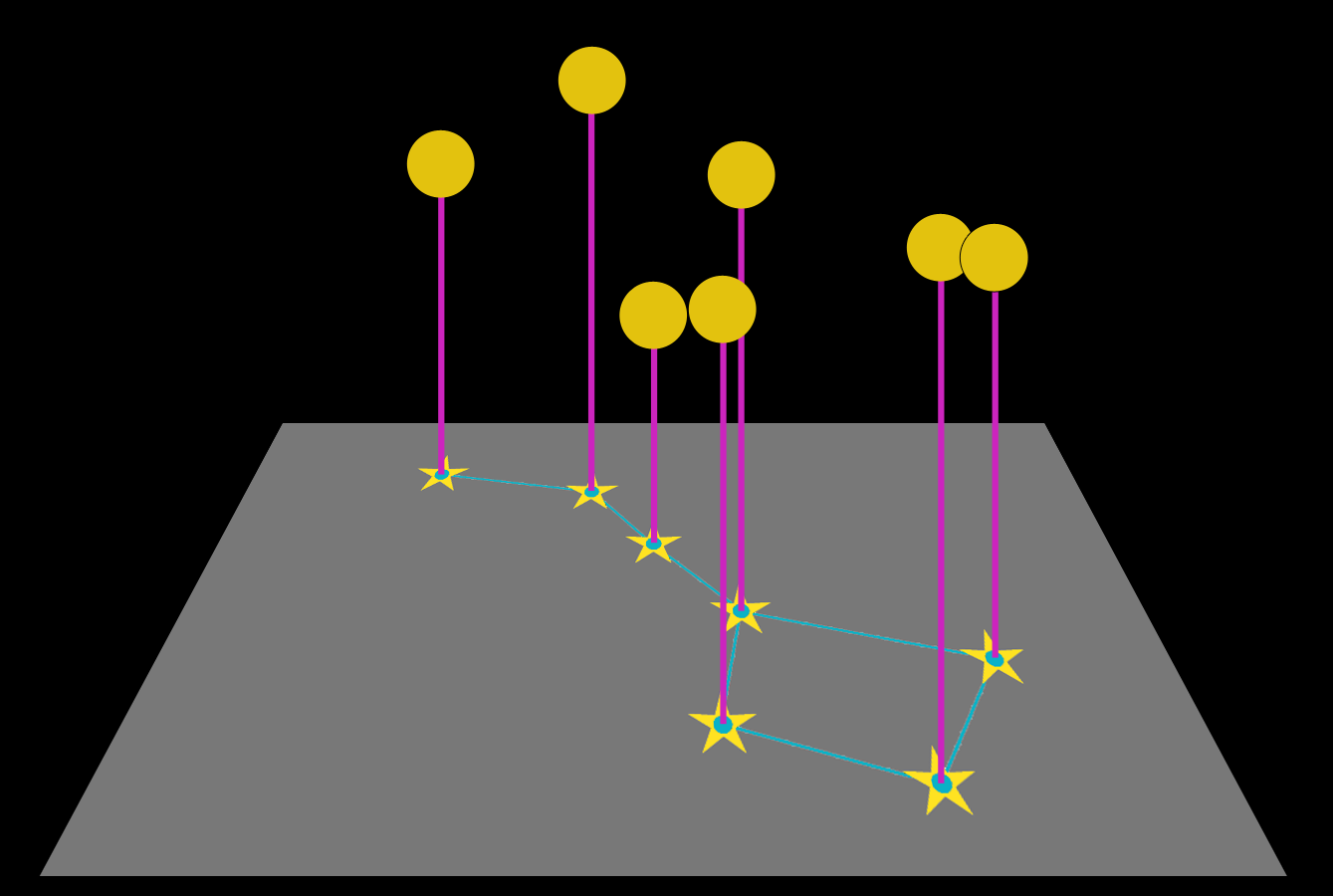

In the gray area in the illustration below, you can see how the Big Dipper constellation (Ursa Major) looks when viewed from Earth (the usual physical placement of we humans). In the black area, the yellow circles show how it might look from another angle, far away in outer space. The familiar Big Dipper shape is a flat, two-dimensional pattern that looks like a stylized ladle. But if we could zoom out into space and fly around the seven stars that make up the constellation, we would see very different patterns, none of which would look familiar. The reality of those stars is that they exist in three dimensions, and it is only from the surface of Earth that we see them as the Big Dipper.[1]

In the same way, figurative positionality also influences the ways we perceive ‘reality’. Depending on the makeup of this composite lens, concepts and objects may appear to us very differently. Being a scientist, artist, or philosopher is like looking at a set of stars from the surface of the Earth, a spaceship near Alpha Centauri, or a wormhole that connects us to other dimensions. Said otherwise, reality is relative—a relationship between us, the observers, and it, the thing we perceive as real.

Discussion Questions

- Identify five aspects of your own identity that contribute to your positionality. In other words, what ‘lenses’ (educational, cultural, social, etc.) do you use to perceive and understand the realities around you? How easy or hard do you think it would be to exchange these lenses for another set?

- Why is it important for social science researchers to acknowledge and account for their own positionality? Name some examples of research contexts in which a researcher’s positionality could radically (or subtly) affect the ways they understand and write about those contexts.

Exercises

Taking Multiple Positions on a Social Context

Imagine a social context like a party, a shop, or a park. Using household items (toys, paper, building blocks, tools, etc.), create a simple set-up (on a desk or table) that represents this social context. Include elements of the built environment (architecture, designed objects, food, technologies, etc.) and the natural environment (people, plants, animals, soil, water, light). Imagine a scenario playing out and what you might do to demonstrate that scenario to others with your set-up.

- Place three or four colleagues around the set-up, in different physical positions. Be creative in your placements, in terms of distance from the table/desk, the viewing angle, and the people’s sight lines.

- Ask your colleagues to take notes on what is happening as you act out your scenario with the elements of your set-up. Although you can speak or make sounds as you do so, do not describe to your colleagues exactly what is happening (i.e., let them interpret).

- Once you have acted out your scenario, ask each of your colleagues to describe to the class what happened, based on their notes. (You can choose to have the other colleague-observers step out of the room until it is their turn to describe the scenario.)

- Ask the rest of the class to note differences among the colleagues’ accounts, including ideas about why their physical positionality might have affected these descriptions. Ask the colleagues to also consider their own figurative positionality (differences in identity, education, experiences, disciplines), and how this influenced what they perceived.

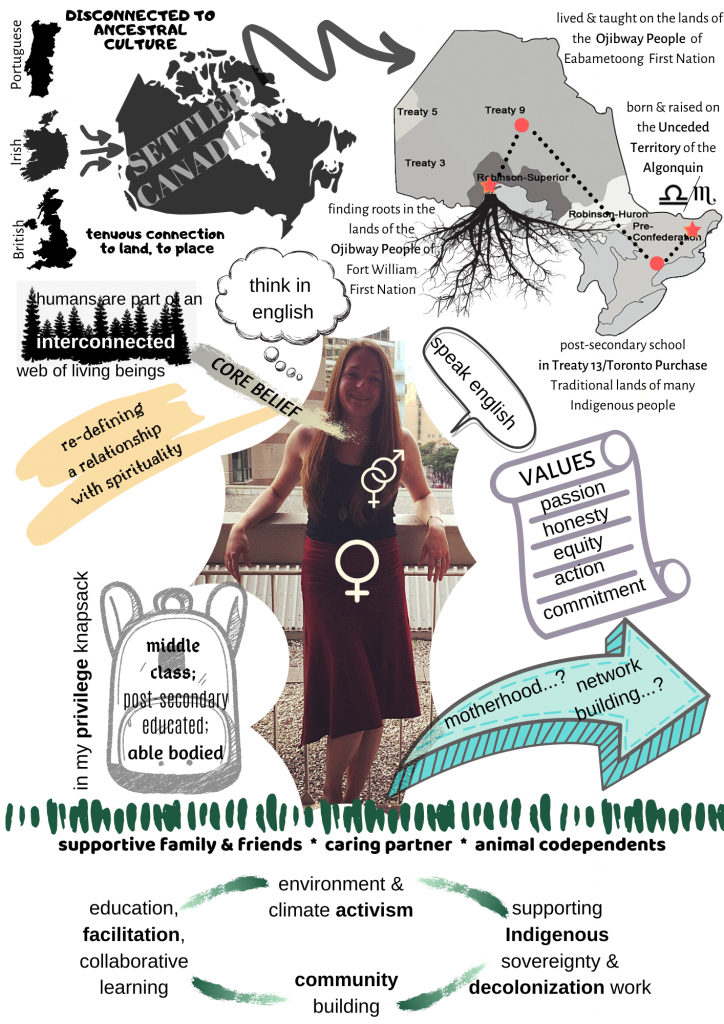

Make a Self-Positioning Sketch

In the image below, Courtney has depicted herself and multiple elements of her past, present, and future. Together they form a representation of her positionality in the world: a stance, a filter, an angle on all that she perceives.

As an exercise, make your own sketch or collage, including as many parts of your life that you think bring an influence to the ways in which you view the world and its ‘truths’. Then:

- Exchange sketches with another student in the class, and discuss with them the similarities and differences between the two sketches.

- With your partner, pick a subject or issue related to your work in class and discuss your perspectives on it, bearing in mind your different (or similar) positionalities. Make reference to the sketches when noting the ways you agree or disagree. How does your positionality help you see this issue?

Additional self-reflective questions:

- It is one thing to create a representation of your positionality for yourself and another to think about how you share it with others. How do you currently position your perspective when you are introducing yourself (or your work) to others?

- Consider the sketch you just made. What aspects of your positionality do you omit when you introduce yourself to someone for the first time? Why?

- How does the way you position yourself change depending on the audience? (e.g., in academic work, in a racially mixed space, in a pre- dominantly white space, in a predominantly Indigenous space.) Why?

Additional Resources

Anderson, C. R. (2020). Confronting the Institutional, Interpersonal and Internalized Challenges of Performing Critical Public Scholarship. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 19(1), 270–302.

Cousin, G. (2010). Positioning positionality. New approaches to qualitative research: Wisdom and uncertainty, 9–18.

Goffman, E. (1986). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Northeastern University Press.

Manohar, N., Liamputtong, P., Bhole, S., & Arora, A. (2017). Researcher positionality in cross-cultural and sensitive research. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 1–15.

- In fact, the Big Dipper is recognizable from the Moon, or from a camera on a Mars landing module. Relatively small differences in physical positionality don’t have much difference in the way we see a constellation. In the same way, subtle differences in figurative positionality—say, between how a sociologist and an anthropologist view a wedding party—might not alter how that reality is perceived in a huge way either. But then again, they might. ↵