Landscape

Ben Garlick and Rachel Hunt

Ben Garlick lectures in Geography at York St John University, U.K. His research interests include the history and culture of conservation (primarily in the U.K.), and the relationship between literature and the meanings of landscape. His current research explores U.K. conservation landscapes, and the work of authors Nan Shepherd and John Berger.

Rachel Hunt is a Lecturer in Geography at the University of Edinburgh, UK. Her research interests sit at the interface of cultural geography, historical geography and the geographies of wellbeing. Her current research focus falls into three related areas: cultural geographies of landscape and land; rural lives and leisure; and the links between landscape experience and well-being.

A Visit to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

“Landscape” is a common term in discussions of human-environmental relations. But what is landscape?

To answer this question, let us consider one of the places thought of as a landscape: the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), near Wakefield, in northern England, U.K. The Cambridge Dictionary defines landscape as “a large area of countryside, usually one without many buildings or other things that are not natural; a view or picture of the countryside.” The YSP certainly fits the bill. Established in 1977 within the grounds of Bretton Hall—an eighteenth-century country estate—YSP showcases nearly 100 artworks amidst 500 acres of grass, woodland and lakeside (YSP, n.d.). Gazing across the estate, we can understand the landscape in different ways, from different cultural approaches, expanding on the dictionary definition offered above. These are certainly productive surroundings to consider the many, interwoven, meanings of landscape.

Leaving the car park, we encounter the parkland arranged before us as a typical rural scene: grassy slopes gently lead down to a ribbon of water framed by trees; the form of the stately house pokes through, breaking up the view. A picturesque sight indeed—it is Nature as art (Figure 1). But to talk about and see it in this way reveals the ‘landscape’ not as a neutral “area of countryside” or simple backdrop, but as a cultural ideal or visual category, filled with specific meanings. Landscape here is what art critic John Berger (1972) termed a ‘way of seeing’ the world, and one that is locatable within a specific cultural-historic context.

The rules of linear perspective and the many, many rural vistas found adorning gallery walls—not to mention calendars, postcards and social media—depict such views as desirable, and arranged for an observer to consume. In other words, such images, circulating throughout society, inform our evaluation of our physical surroundings in terms of the conventions of art.

However, cultural specificity is important. This way of seeing YSP owes a particular debt to European traditions of landscape painting. Depictions of the environment in Western art are different to those from other contexts, times, and places (for example, Chinese landscape painting). Thus, a visitors’ ways of perceiving the landscape of YSP changes depending on their positionality. Gender, race, ethnicity, and socio-economic position all affect how it is understood. Personal and shared histories and subjectivities, alongside our lived experiences of landscapes and cultures elsewhere, inform these responses (Tolia-Kelly, 2010).

Of course, YSP’s management have a vision for how the park’s landscape should look, perhaps contrasting with that of other land-users, now or in the past. Their rules and regulations, not to mention wider cultural norms, produce a set of expectations for how we engage with and evaluate this place. Nevertheless, other ways of using and valuing the park proliferate too, for example as a picnic spot rather than an open-air gallery. In this way, alongside a set of visual conventions, ‘landscape’ usefully characterises a bundle of rules, assumptions, or discourses; flowing from, and reinforcing, particular ‘ways of seeing’ to constitute practical, and particular, cultures of landscape (see Matless, 2014).

From our elevated vantage point, gazing across the sculpture-dotted parkland, it is appealing to consider landscape in purely visual terms. One may be tempted to view the scene as natural and timeless, exemplifying the myth of a bountiful, pastoral landscape where humans and land coexist harmoniously. But the landscape is also more than what is seen.

Through the centre of YSP runs a lake: excavated and dammed at one end in the mid-18th century at the behest of a wealthy landowner, fond of entertaining high-society guests with fireworks and mock-naval battles (YSP, n.d.). Today, visitors arrive from across Yorkshire (and beyond) to appreciate the variety of artworks, as well as relish the opportunities afforded to urban dwellers by a large green space. For YSP to function as an accessible visitor attraction, numerous volunteers and paid staff work to control entry, manage parking, guide guests, sell refreshments, combat growing vegetation, and repair eroding paths.

Consequently, embedded in this environment is the labour of generations, past and present, making and remaking the landscape what it is (see social nature). YSP is the outcome of these (often hidden) exertions, including complex histories of ownership, management, and purchase (see Olwig, 2016). Its present appearance, reflecting familiar aesthetic ideals of an ‘English country landscape’, is inseparable from the material, social, and economic struggles—the work—producing it.

And lest we forget the sheep! Visual representations of the ‘rural’ often feature familiar animal icons: the expected, ‘natural’ inhabitants. But more than this, our interactions with such beings—as well as their own activities—also shape how landscapes are made and experienced. For some visitors, these grazing animals might add rural charm. For others, their skittish demeanour and faeces detract from an otherwise pleasant parkland. And, whilst their presence reflects active agricultural management (herding the flock and grazing as a strategy to keep vegetation in check), they also have a role in making this landscape what it is. Roaming the park on their own terms, sheltering from rain and sun, approaching, or fleeing visitors; such animal comings and goings are part of this landscape’s liveliness.

In addition to its social construction—whether through histories of art or working the land—YSP is experienced. Standing looking across the park affords a view of the land by virtue of the body’s senses and situation within its immediate surroundings. Light hits our optic nerve, which becomes images. We might feel a light breeze, the prickle of sunburn, a dull calf-ache from walking up the steep incline. We may even smell sheep poo, or a nearby picnic lunch. In this vein, landscapes are a gathering of such bodily sensations, each revealing the different ways in which the body interacts with its environment. Might YSP appear so inviting if one suffered sunstroke, or was soaked by a rainstorm? And what of those with differently abled bodies, navigating the grassy slopes with mobility aids, or negotiating sculptures with a visual impairment? Different bodies all play a part in creating the landscape we experience, and, consequently making the same landscape a different experience for others (Wylie, 2018).

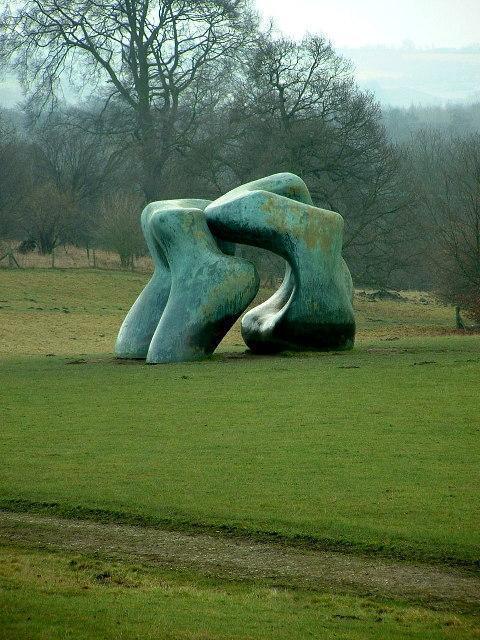

We might appreciate the way in which the sculptures themselves texture such experiences (see Warren, 2012). Figure 2 depicts Henry Moore’s Large Two Forms, positioned near the shore of the lake. Glinting in the sun, glistening in the rain, these bulky bronzes invite curiosity as their qualities change. Circling onlookers peer at them. The sculptures, in turn, reframe their surroundings, from different angles and in different ways for each visitor. The installation disrupts lines of sight, buffers wind, deflects rain, refracts sound, and offers an arresting subject for photographs. Like the sheep, the sculptures are involved in an experience of landscape. They are both features of it, and active things making possible a particular appreciation of the environment.

And what of the other, less tangible forces captured by the term ‘landscape’? After all, environmental experience is also shaped by emotions, feelings, sensations—what we might collectively call affects—changing encounters in various ways that exceed our ability to adequately put them into words. Such affects come together to give landscapes an atmosphere—a ‘vibe’ or ‘energy’ associated with place. For one of us, YSP holds personal significance as a site that nearly hosted a wedding proposal. On a late September afternoon, the park was a damp, drizzly place; anxiety swirled around the upcoming question. The ring clutched in the pocket; a sense of exposure being out in public. The atmosphere was all wrong. It didn’t feel right.

So, what is landscape?

As YSP helps us understand, it is a great many things. Landscape names a construction of our cultural imaginations; the accumulated traces of overlapping labours; a domain of bodily experience; a field of material forces; and a space charged with feeling, memory, and emotion. The sculpture park is simultaneously a particular physical environment that we encounter and perceive, and a site prompting all manner of conflicting questions about the ways that people understand and relate to such environments. If there is a common thread to landscape, it is a concern with how we encounter our surroundings, as well as the role played by the process, forces, and other beings (human or not) shaping that encounter. Landscape is no simple matter.

Discussion Questions

- Picture a ‘landscape’—any place you associate with this term. What are some of the different ways in which your experience of this environment might be affected by your gender, race, ethnicity, cultural, or socio-economic background? Can you think of any other aspects of your social identity that might shape how you experience this place?

- Choose a piece of ‘landscape art’ and consider it as a story, told from a certain perspective. What is the story being told, why, by whom, for what purpose, and to what effect?

- Working with a partner, picture a specific landscape you have visited recently in your mind, and describe to them any smells, textures, sounds, tastes, or emotions you associate with that scene. (Don’t tell them what the landscape looks like, however.) Your partner should then describe what they can ‘see’ based on these descriptions. Compare their response with the example you were thinking of. What might this tell us about how landscape is experienced by different people?

References

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of seeing. London: Penguin.

Matless, D. (2014). In the nature of landscape: Cultural geography on the Norfolk Broads. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Olwig, K. (2016). The meanings of landscape: Essays on place, space, environment and justice. Abingdon: Routledge.

Tolia-Kelly, D. (2010). Landscape, race, and memory: Material ecologies of citizenship. Abingdon: Routledge.

Warren, S. (2012). Audiencing James Turrell’s Skyspace: Encounters between art and audience at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. cultural geographies, 20(1): 83-102.

Wylie, J. (2018). Landscape and phenomenology. In: Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., and Atha, M. (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies 2nd Ed. (Abingdon: Routledge): 127-138.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park. (no date). ‘Heritage: Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Bretton Estate’. https://ysp.org.uk/_assets/media/editor/About_YSP/history-of-bretton-estate-leaflet.pdf Accessed 20th October 2021.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park. (2018, May 16). An Introduction to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1w58UGpza6k